The Smoothest Con Man That Ever Lived

“Count” Victor Lustig once sold the Eiffel Tower to an unsuspecting scrap-metal dealer. Then he started thinking really big

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/66/d3/66d36e6c-c614-4f6d-9641-2252b57e4d56/smoothest_con_man.jpg)

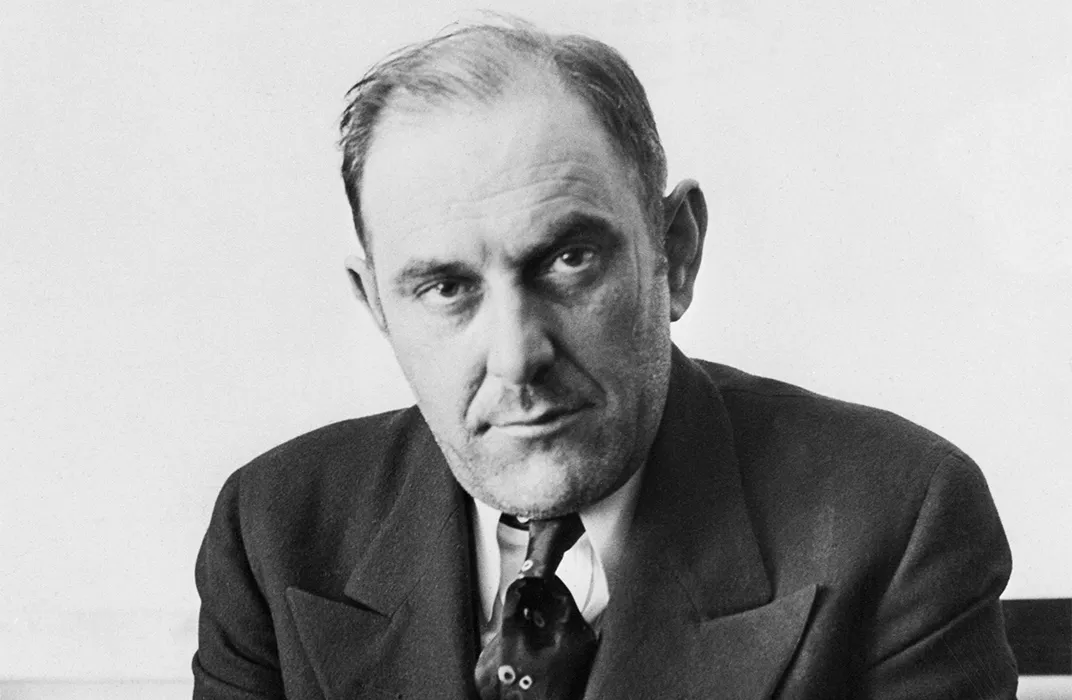

On a Sunday night in May 1935, Victor Lustig was strolling down Broadway on New York’s Upper West Side. At first, the Secret Service agents couldn’t be sure it was him. They’d been shadowing him for seven months, painstakingly trying to learn more about this mysterious and dapper man, but his newly grown mustache had thrown them off momentarily. As he turned up the velvet collar on his Chesterfield coat and quickened his pace, the agents swooped in.

Surrounded, Lustig smiled and calmly handed over his suitcase. “Smooth,” was how one of the agents described him, noting a “livid scar” on his left cheekbone and “dark, burning eyes.” After chasing him for years, they’d gotten a close-up view of the man known as “the Count,” a nicknamed he’d earned for his suave and worldly demeanor. He had long sideburns, agents observed, and “perfectly manicured nails.” Under questioning he was serene and poised. Agents expected the suitcase to contain freshly printed bank notes from various Federal Reserve series, or perhaps other tools of Lustig’s million-dollar counterfeiting trade. But all they found were expensive clothes.

At last, they pulled a wallet from his coat and found a key. They tried to get Lustig to say what it was for, but the Count shrugged and shook his head. The key led agents to the Times Square subway station, where it opened a dusty locker, and inside it agents found $51,000 in counterfeit bills and the plates from which they had been printed. It was the beginning of the end for the man described by the New York Times as an “E. Phillips Oppenheim character in the flesh,” a nod to the popular English novelist best known for The Great Impersonation.

Secret Service agents finally had one of the world’s greatest imposters, wanted throughout Europe as well as in the United States. He’d amassed a fortune in schemes that were so grand and outlandish, few thought any of his victims could ever be so gullible. He’d sold the Eiffel Tower to a French scrap-metal dealer. He’d sold a “money box” to countless greedy victims who believed that Lustig’s contraption was capable of printing perfectly replicated $100 bills. (Police noted that some “smart” New York gamblers had paid $46,000 for one.) He had even duped some of the wealthiest and most dangerous mobsters—men like Al Capone, who never knew he’d been swindled.

Now the authorities were eager to question him about all of these activities, plus his possible role in several recent murders in New York and the shooting of Jack “Legs” Diamond, who was staying in a hotel room down the hall from Lustig’s on the night he was attacked.

“Count,” one of the Secret Service agents said, “you’re the smoothest con man that ever lived.”

The Count politely demurred with a smile. “I wouldn’t say that,” he replied. “After all, you have conned me.”

Despite being charged with multiple counts of possession of counterfeit currency and plates, Victor Lustig wasn’t done with the con game quite yet. He was held at the Federal Detention Headquarters in New York, believed to be “escape proof” at the time, and scheduled to stand trial on September 2, 1935. But prison officials arrived at his cell on the third floor that day and were stunned. The Count had vanished in broad daylight.

Born in Austria-Hungary in 1890, Lustig, became fluent in several languages, and when he decided to see the world he thought: Where better to make money than aboard ocean liners packed with wealthy travelers? Charming and poised at a young age, Lustig spent time making small talk with successful businessmen—and sizing up potential marks. Eventually, talk turned to the source of the Austrian’s wealth, and reluctantly he would reveal—in the utmost confidence—that he had been using a “money box.” Eventually, he would agree to show the contraption privately. He just happened to be traveling with it. It resembled a steamer trunk, crafted of mahogany but fitted with sophisticated-looking printing machinery within.

Lustig would demonstrate the money box by inserting an authentic hundred-dollar bill, and after a few hours of “chemical processing,” he’d extract two seemingly authentic hundred-dollar bills. He had no trouble passing them aboard the ship. It wasn’t long before his wealthy new friends would inquire as to how they too might be able to come into possession of a money box.

Reluctantly again, the Count would consider parting with it if the price was right, and it wasn’t uncommon for several potential buyers to bid against one another over several days at sea. Lustig was, if nothing else, patient and cautious. He would usually end up parting (at the end of the voyages) with the device for the sum of $10,000—sometimes two and three times that amount. He would pack the machine with several hundred-dollar bills, and after any last-minute suspicions had been allayed through successful test runs, the Count would disappear.

By 1925, however, Victor Lustig had set his sights on grander things. After he arrived in Paris, he read a newspaper story about the rusting Eiffel Tower and the high cost of its maintenance and repairs. Parisians were divided in their opinion of the structure, built in 1889 for the Paris Exposition and already a decade past its projected lifespan. Many felt the unsightly tower should be taken down.

Lustig devised the plan that would make him a legend in the history of con men. He researched the largest metal-scrap dealers in Paris. Then he sent out letters on fake stationery, claiming to be the Deputy Director of the Ministere de Postes et Telegraphes and requesting meetings that, he told them, might prove lucrative. In exchange for such meetings, he demanded absolute discretion.

He took a room at the Hotel de Crillon, one of the city’s most upscale hotels, where he conducted meetings with the scrap dealers, telling them that a decision had been made to take bids for the right to demolish the tower and take possession of 7,000 tons of metal. Lustig rented limousines and gave tours of the tower—all to discern which dealer would make the ideal mark.

Andre Poisson was fairly new to the city, and Lustig quickly decided to focus on him. When Poisson began peppering him with questions, Lustig baited his lure. As a public official, he said, he didn’t earn much money, and finding a buyer for the Eiffel Tower was a very big decision. Poisson bit. He’d been in Paris long enough to know what Lustig was getting at: The bureaucrat must be legitimate; who else would dare seek a bribe? Poisson would pay the phony deputy director $20,000 in cash, plus an additional $50,000 if Lustig could see to it that his was the winning bid.

Lustig secured the $70,000 and in less than an hour, he was on his way back to Austria. He waited for the story to break, with, possibly, a description and sketch of himself, but it never did. Poisson, fearful of the embarrassment such a disclosure would bring upon him, chose not to report Lustig’s scam.

For Lustig, no news was good news: He soon returned to Paris to give the scheme another try. But, ever cautious, the Count came to suspect that one of the new scrap dealers he contacted had notified the police, so he fled to the United States.

In America, Lustig returned to the easy pickings of the money box. He assumed dozens of aliases and endured his share of arrests. In more than 40 cases he beat the rap or escaped from jail while waiting trial (including the same Lake County, Indiana, jail from which John Dillinger had bolted). He swindled a Texas sheriff and a county tax collector out of $123,000 in tax receipts with the money-box gambit, and after the sheriff tracked him down in Chicago, the Count talked his way out of trouble by blaming the sheriff for his inexperience in operating the machine (and returning a large sum of cash, which would come back to haunt the sheriff).

In Chicago, the Count told Al Capone he needed $50,000 to finance a scam and promised to repay the gangster double his money in just two months. Capone was suspicious, but handed his money over. Lustig stuffed it in a safe in his room and returned it two months later; the scam had gone horribly wrong, he said, but he had come to repay the gangster’s loan. Capone, relieved that Lustig’s scam wasn’t a complete disaster and impressed with his “honesty,” handed him $5,000.

Lustig never intended to use the money for anything other than to gain Capone’s trust.

In 1930, Lustig went into partnership with a Nebraska chemist named Tom Shaw, and the two men began a real counterfeiting operation, using plates, paper and ink that emulated the tiny red and green threads in real bills. They set up an elaborate distribution system to push out more than $100,000 per month, using couriers who didn’t even know they were dealing with counterfeit cash. Later that year, as well-circulated bills of every denomination were turning up across the country, the Secret Service arrested the same Texas sheriff Lustig had swindled; they accused him of passing counterfeit bills in New Orleans. The lawman was so enraged that Lustig had passed him bogus money that he gave agents a description of the Count. But it wasn’t enough to keep the sheriff out of prison.

As the months passed and more phony bills—millions of dollars’ worth—kept turning up at banks and racetracks, the Secret Service tried to track Lustig down. They referred to the bills as “Lustig money” and worried that they might disrupt the monetary system. Then Lustig’s girlfriend, Billy May, found out he was having an affair with Tom Shaw’s mistress. In a fit of jealousy, she made an anonymous call to the police and told them where the Count was staying in New York. Federal agents finally found him in the spring of 1935.

As he awaited trial, Lustig playfully bragged that no prison could hold him. On the day before his trial was to begin, dressed in prison-issue dungarees and slippers, he fashioned several bedsheets into a rope and slipped out the window of the Federal Detention Headquarters in lower Manhattan. Pretending to be a window washer, he casually wiped at windows as he shimmied down the building. Dozens of passersby saw him, and they apparently thought nothing of it.

The Count was captured in Pittsburgh a month later and pleaded guilty to the original charges. He was sentenced to 20 years in Alcatraz. On August 31, 1949, the New York Times reported that Emil Lustig, the brother of Victor Lustig, had told a judge in a Camden, New jersey, court that the infamous Count had died at Alcatraz two years before. It was most fitting: Victor Lustig, one of the most outrageously colorful con men in history, was able to pass from this earth without attracting any attention.

Sources

Articles: ” ‘Count’ Seizure Bares Spurious Money Cache,” Washington Post, May 14, 1935. “‘Count Seized Here with Bogus $51,000″ New York Times, May 14, 1935. “Federal Men Arrest Count, Get Fake Cash,” Chicago Tribune, May 14, 1935. “‘The Count’ Escapes Jail on Sheet Rope,” New York Times, September 2, 1935. “The Count Made His Own Money,” by Edward Radin, St. Petersburg Times, February 20, 1949.”How to Sell the Eiffel Tower (Twice)” by Eric J. Pittman, weirdworm.com. “Count Lustig,” American Numismatic Society, Funny Money, http://numismatics.org/Exhibits/FunnyMoney2d. ”Robert Miller, Swindler, Flees Federal Prison,” Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1935. “Knew 40 Jails, ‘Count’ Again Falls in Toils,” Washington Post, September 26, 1935. “Lustig, ‘Con Man,’ Dead Since 1947,” New York Times, August 31, 1949.

Books: PhD Philip H. Melanson, The Secret Service: The Hidden History of an Enigmantic Agency, Carroll & Graf, 2002.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)