The Spiritualist Who Warned Lincoln Was Also Booth’s Drinking Buddy

What did Charles Colchester know and when did he know it?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/3b/233b7522-d7a3-4598-b42c-f57ece090cf1/mar2015_i05_lincolnmedium-cr.jpg)

“I cannot be shut up in an iron cage and guarded,” Abraham Lincoln said irritably when his friend Leonard Swett worried that the chief executive’s security was inadequate. A president must go among the people, Lincoln explained. “One man’s life is as dear to him as another’s, and if a man takes my life, he may be reasonably sure that he will lose his own,” he told another friend, Rep. Cornelius Cole of California. The president had thought of assassination, yes, “but I do not believe it is my fate to die in this way.”

Lincoln’s friends remained worried. As the Civil War entered its final months, the Confederacy was thrashing like a harpooned shark, plotting to rob Northern banks, raid prison camps, wreck trains and send disease-infected clothing to Washington, D.C. One night the Rebels tried to set ablaze some 19 hotels and other public buildings in New York City. The Yankees had already targeted Jefferson Davis for capture or worse. Would the South now, in response, suspend the unwritten rules that had protected Lincoln from a bullet?

Charles J. Colchester also warned Lincoln. He was no solicitous friend, like Swett or Cole. Indeed, Lincoln hardly knew Colchester. But he was important to Mary Todd Lincoln, the president’s wife, and had become a regular visitor to the White House. Oddly, this strange character, a spiritualist and medium, was the one person Lincoln should have heeded. Colchester needed none of his prophetic powers to realize the president was in danger. His information likely came from the best of earthly sources—his friend John Wilkes Booth.

The story of Lincoln, Booth and Colchester—which has been overlooked in the considerable literature on the president’s assassination—began, in a sense, on the afternoon of February 20, 1862. About 5 p.m. that day, the Lincolns’ son Willie died at age 11, apparently of typhoid fever. Sweet-tempered Willie was the most intelligent and best-looking of the four Lincoln boys, and the one most like his father in personality. Both parents idolized him. Having lost their son Eddie 12 years earlier, when he was 3, they were devastated to be revisited by this peculiarly cruel sort of tragedy.

“His death was the most crushing affliction Mr. Lincoln had ever been called upon to pass through,” recalled the artist Francis Carpenter, who lived in the White House for six months while he painted the famous portrait of the president and his cabinet at the first reading of the Emancipation Proclamation. Willie had died on a Thursday. The following Thursday, Lincoln shut himself up in the Green Room to grieve, and he began a routine of withdrawing there each succeeding Thursday. Mary and her older sister Elizabeth Todd Edwards became alarmed over his state of mind, so they arranged for the Rev. Francis Vinton of Trinity Church in New York City to visit the president. Imperious and opinionated, Vinton, a lawyer and soldier by education, told Lincoln he was fighting with God by indulging his grief in this manner.

Lincoln heard Vinton out as if he were in a stupor until the minister said, “Your son is alive.”

“Alive! Alive!” Lincoln repeated, jumping up from a sofa. “Surely you mock me.”

“My dear sir,” Vinton responded as he placed an arm around the president. “Seek not your son among the dead. He is not there. He lives today in Paradise.” Vinton’s hopeful words notwithstanding, the cold comfort of the president’s fatalism was his chief solace. As he explained to his former law partner, William Herndon: “Things were to be, and they came, irresistibly came, doomed to come.”

The war’s relentless demands on Lincoln’s attention gradually drew him back from despair. He put a broad black ribbon around his trademark stovepipe hat in Willie’s memory and moved on. The ribbon was still there when he was murdered three years later.

Mary Lincoln took to her bed for weeks after Willie died and remained inconsolable after she emerged in mourning black. More conventionally religious than her husband, she was nevertheless unable to accept the teaching of her Presbyterian faith that Willie had gone to God in peace and rest. She did not want to part with him. Perhaps she didn’t have to, friends said. They told her that Willie was still here—anxious to see her, in fact—and simply waited on the other side of a veil that could be lifted by those with the proper gift.

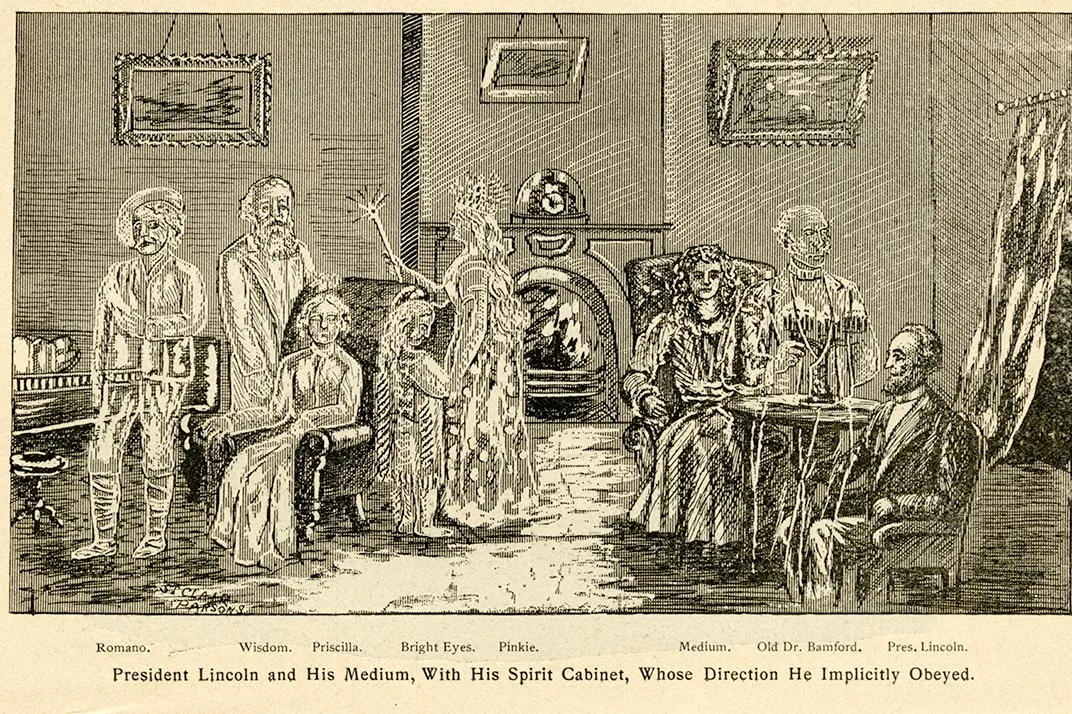

The glad tidings of spiritualism—that the dearly departed were ever present to offer comfort and advice to the living—were powerfully appealing in the 19th century, and the movement’s influence soared with the suffering produced by the war. Spiritualist newspapers proclaimed the faith, and circles of believers established themselves in the leading cities. The Washington circle counted among its members a number of government officials. Warren Chase, a traveling lecturer for the movement, thought the interest shown in spiritualism was greater in the nation’s capital than in any other place.

Mary Lincoln was visited by a succession of “spirit ministers” after Willie’s death. Their impact was palpable. One night she knocked on the door of the Prince of Wales bedroom, where her half-sister Emilie Helm was staying, to talk about Willie. “He lives,” Mary said, her voice trembling. “He comes to me every night and stands at the foot of my bed with the same sweet, adorable smile he has always had.” Sometimes he brought other departed family members with him, like his brother Eddie. “You cannot dream of the comfort this gives me.”

Mary’s eyes were wide and shining and otherworldly as she spoke, and Emilie grew alarmed. “It is unnatural and abnormal,” she wrote in her diary. “It frightens me.”

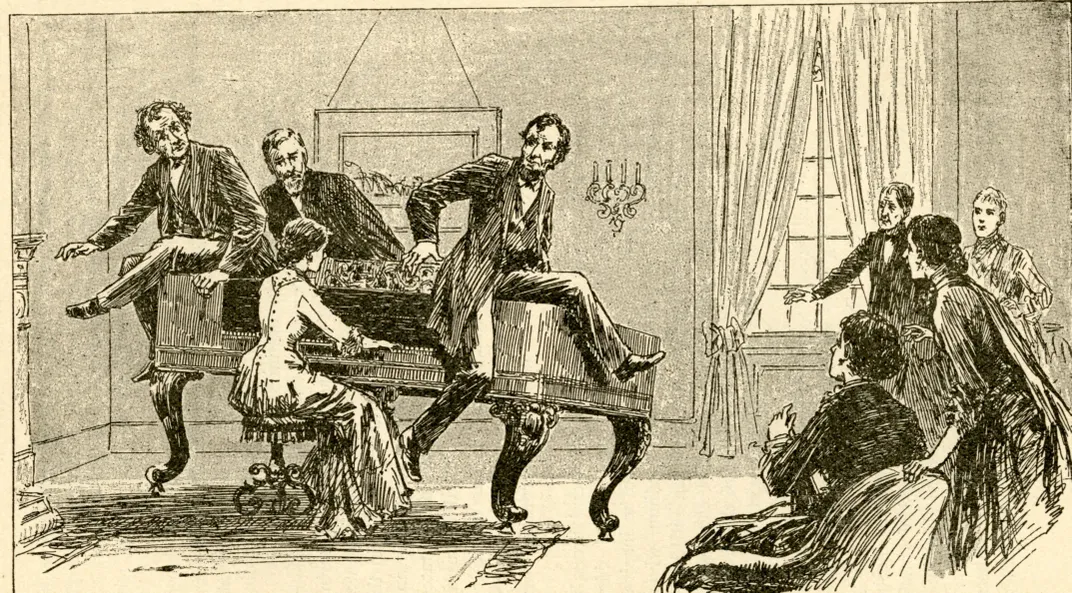

Now it was Lincoln’s turn to worry. Dutiful husband that he was, the president dropped in on her sittings with spiritualists from time to time. Once he tagged along with her to visit Margaret Laurie and her daughter Belle Miller, the so-called witches of Georgetown. It seemed advisable to keep an eye on these occasions, and—given that Miller supposedly had the power to levitate pianos—they might also be entertaining. But the president was never a believer, referring whimsically to the spirit world as “the upper country.” Lincoln believed for most of his life that the soul lost its identity after death.

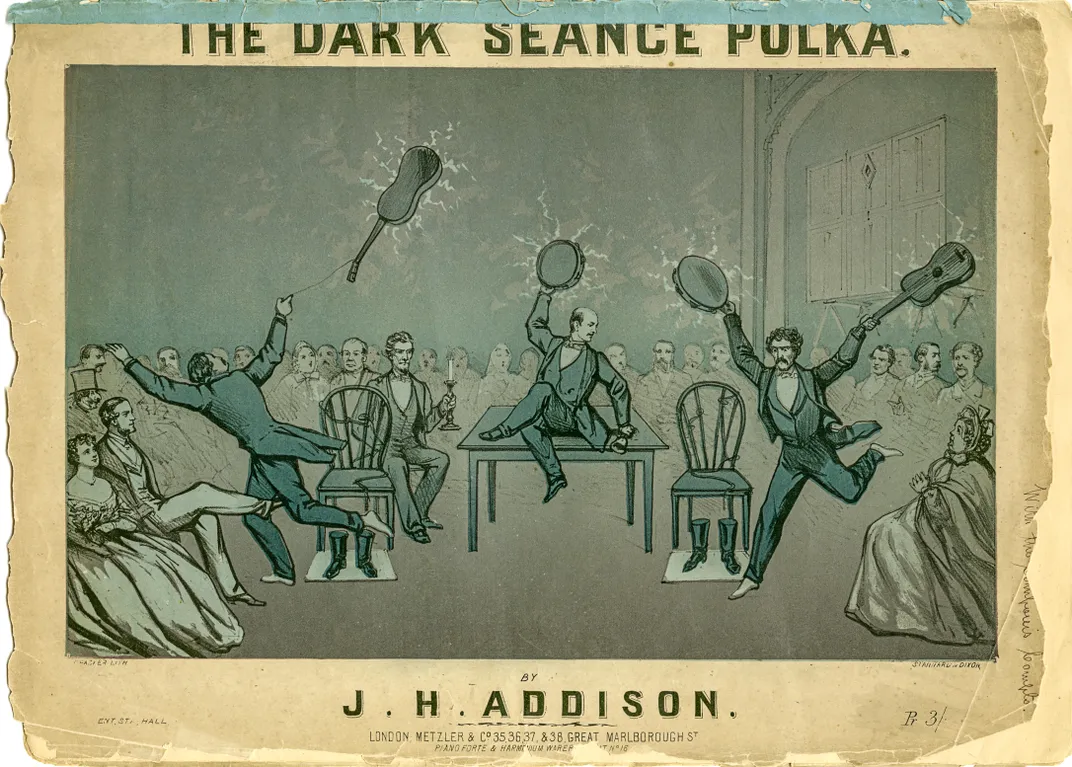

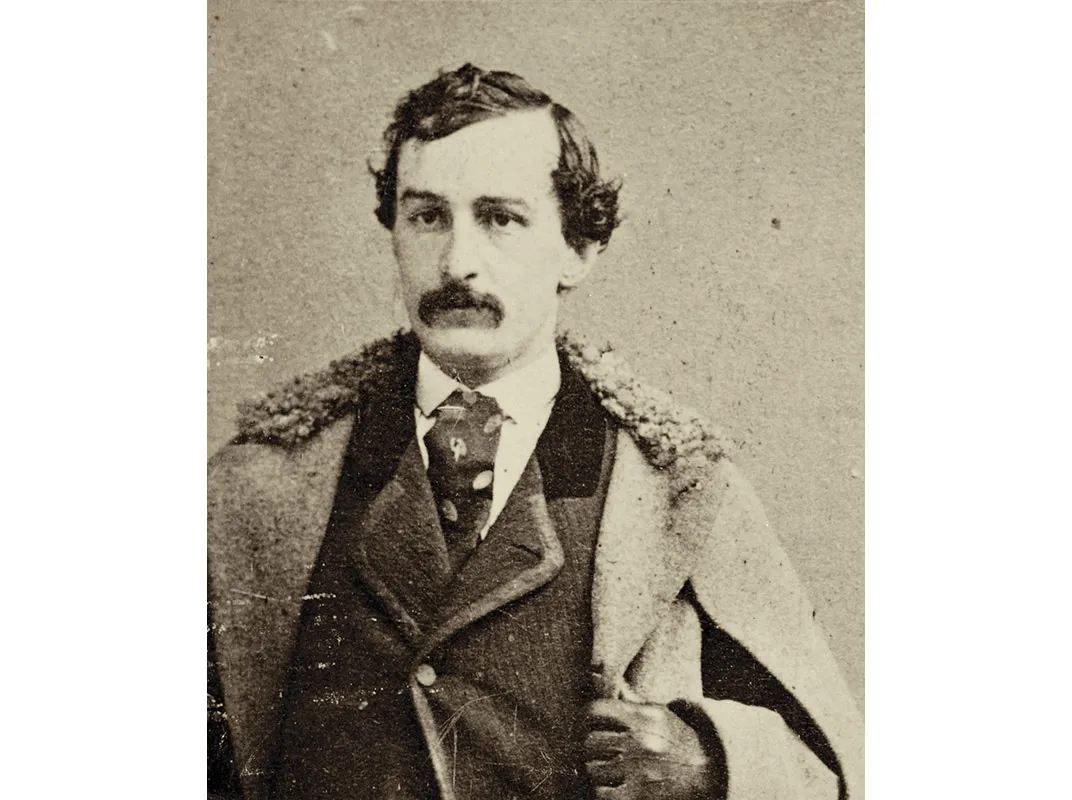

Prominent among the mediums who attended Mary was Charles Colchester, a red-faced, blue-eyed Englishman with a large mustache. Alleged to be the illegitimate son of a duke, this seer professed remarkable powers: He could read sealed letters, cry out the names of visitors’ deceased friends, cause apparitions to appear, and produce words on his forearm in blood-red letters. “Colchester is regarded as the leader of Spiritualism in America,” a Cincinnati newspaper reported, “and, as a consequence, his votaries, believers, and visitors are counted by the hundreds.” To the faithful he was an extraordinarily gifted intermediary with the other side. To skeptics he was a con man who employed sleight of hand, hypnosis and sideshow magic in darkened rooms to fill his pockets at the expense of the troubled and the brokenhearted. (In the fall of 1865, he was convicted in upstate New York of practicing “jugglery,” or sleight of hand, without a license and died in Iowa a few years later.)

Colchester set up shop in Washington in midwar and before long was working his wizardry at the White House and the Soldiers’ Home, where a presidential summer cottage sat on a hill north of downtown. There, at private sittings, the young soothsayer mystified the president and his wife.

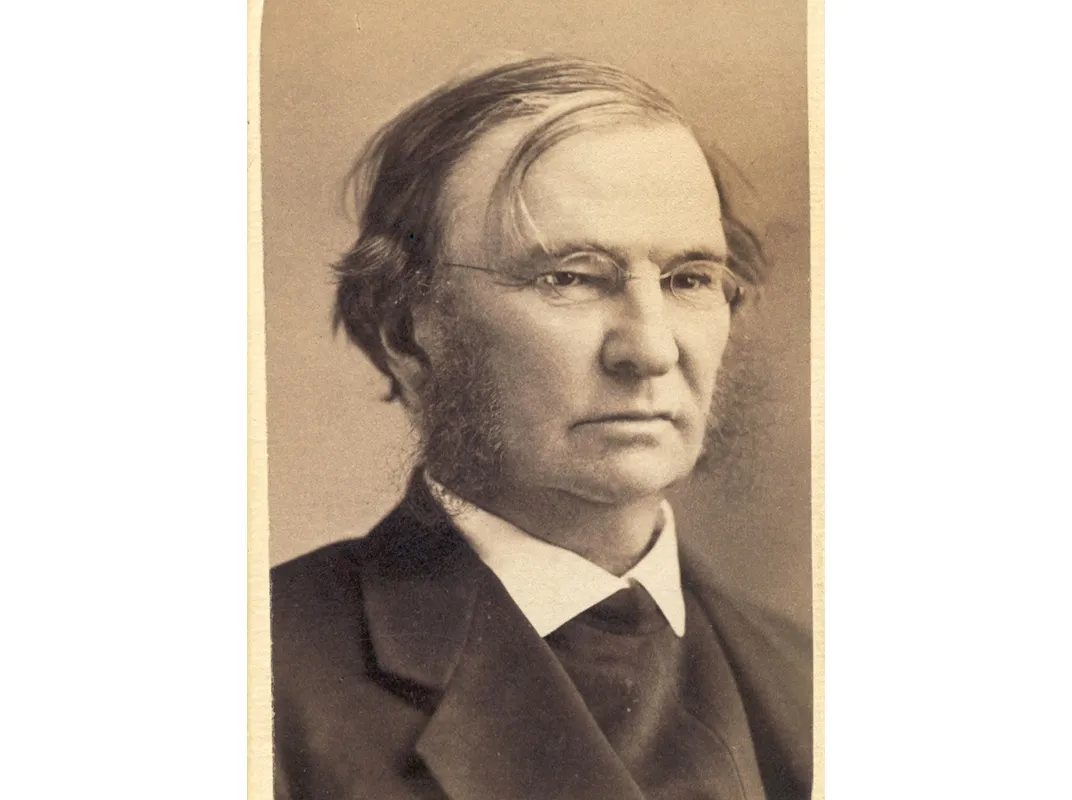

Lincoln was particularly intrigued with Colchester’s eerie ability to summon noises in different parts of a room. Like any rational person, the president wanted to understand what was happening, so he asked Colchester to submit to an examination by Joseph Henry, the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. The medium agreed, and a chagrined Henry reported back to the president that he had no immediate explanation for the phenomenon. (He later learned that Colchester wore a specially designed electrical noisemaker strapped to his biceps. The discovery came quite by chance, after Henry struck up a conversation with a stranger on a train who happened to be the man who had made the device and sold it to Colchester.)

Honest if he liked a client, Colchester admitted to Chase that “he often cheated the fools, as he could easily do it.” Since he was as receptive to distilled spirits as to ethereal ones, most of the money he received for his sittings went straight to whiskey. When friends asked him out for a glass, the convivial Englishman would reply that he must first consult the spirits for guidance. With an earnest look, he would slap his hand on the nearest lamppost, commune intently, then announce that the other world had authorized a libation. Chronically short of cash, he was greedy and deceptive—in a word, trouble.

As a regular on the Washington social circuit, Colchester met John Wilkes Booth. The stage star was living in Washington at the time, plotting to abduct Lincoln as a hostage for the South, when not fantasizing about assassinating him.

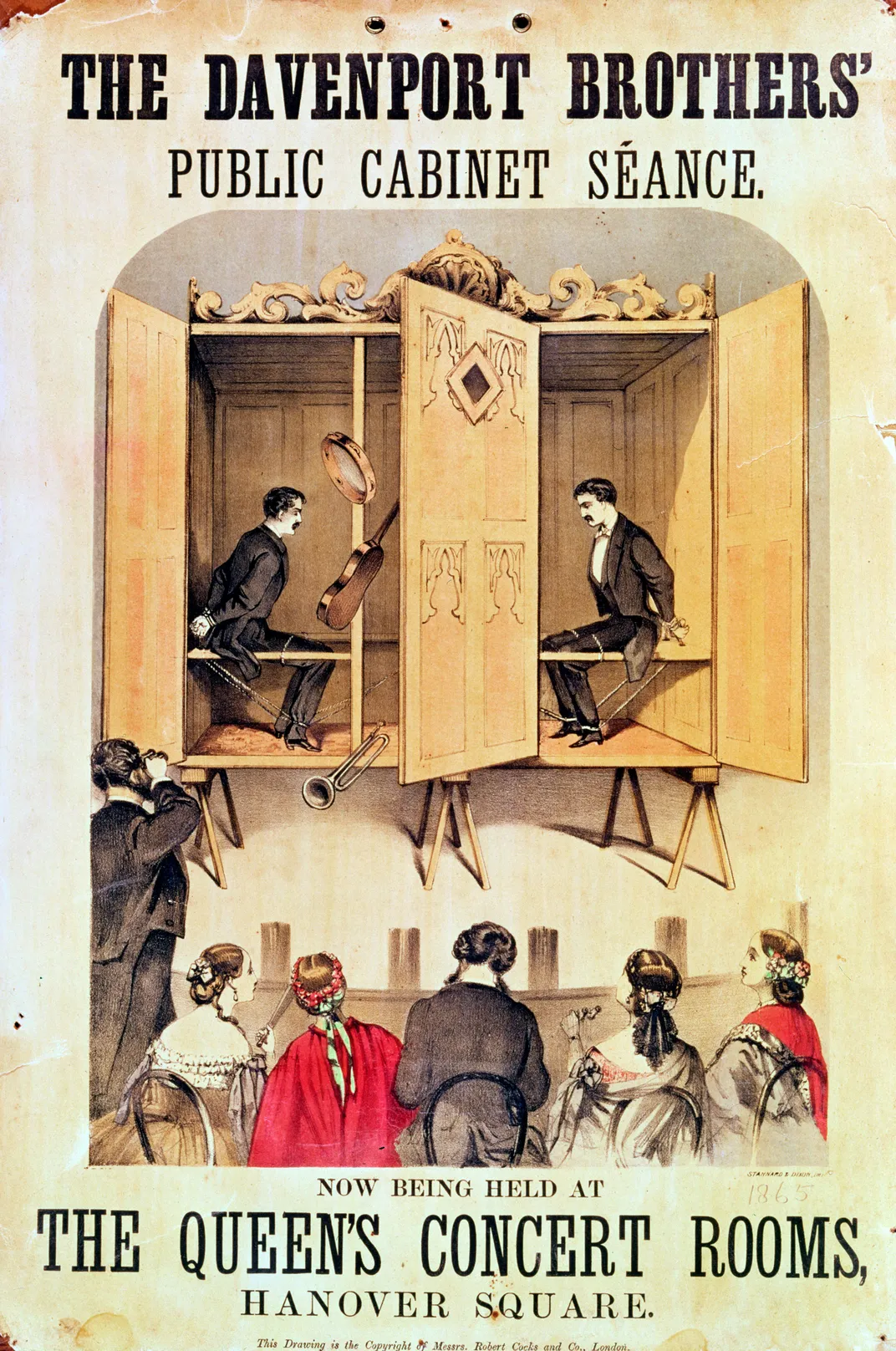

Booth’s interest in spiritualism began in 1863, when his sister-in-law Molly died; inherently superstitious, he attended a number of séances with his widowed brother, Edwin. Later Booth grew strongly attached to the remarkable brothers Ira and William Davenport, magicians who posed as spiritual mediums. When they were tightly bound inside a sealed box with musical instruments, a person outside the box could hear tunes coming from within it. Yet, when the box was opened and the brothers were revealed to be still tied in their original positions, it seemed as if they had summoned a ghostly orchestra to perform. They were “probably the greatest mediums of their kind the world has ever seen,” Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes and a noted spiritualist, once wrote. Booth loved the Davenports and had private sittings with them whenever he could.

In the weeks before the assassination, Booth roomed at the National Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, just six blocks from the Capitol and even closer to Ford’s Theatre. Colchester visited him there often. Besides his ability to contact the dead, Colchester could also tell the future—a useful ability to Booth, who was beginning to think the unthinkable. The pair spent a considerable amount of time together, said George W. Bunker, the National’s room clerk, and they often went out in company. Bunker observed that Colchester was not merely Booth’s friend. It was more than that. Colchester was Booth’s “associate.”

Meanwhile, Colchester made mischief at the White House. Having gained Mary’s trust, he demanded that she get him a free railroad pass from the War Department. Colchester made clear that she would do it or he would make public some very embarrassing facts he had learned during their sittings. Frantic, Mary disclosed the blackmail attempt to Noah Brooks, a member of the president’s inner circle.

Brooks decided to confront the scoundrel. He attended a Colchester séance where everyone sat holding hands around a table on which a drum, a banjo and a bell had been placed. When the lights were extinguished, music began to play from the instruments. Breaking his hands free, Brooks grasped in the direction of the sound and cracked his head on something hard. He held his grip, however, and when a friend struck a match, Colchester’s hand, holding a bell and the drum that had left a gash on Brooks’ head, was in his grasp.

Colchester left the room and refused to return, saying he was “so outraged by this insult.” But Brooks caught up with him at the White House a day or two later and said, “You know that I know you are a swindler and a humbug.” Colchester fled.

In early April 1865, Booth abandoned his plot to kidnap Lincoln to focus on assassinating him. In front of a number of trusted friends in Washington he threatened to kill the president, and one wonders—the record is mute on this point—what Colchester learned of his plans.

That the spiritualist warned Lincoln became clear a few days later. When someone urged the president to be mindful of his safety, he responded, “Colchester has been telling me that.” While warning Lincoln was a stock in trade for mediums, here was one mystic in a position to know what he was talking about. For all his faults, Colchester was the master only of misdemeanor; he had no felony at heart. Lincoln “was too intelligent not to know he was in danger” at times, wrote his secretaries John G. Nicolay and John Hay. “But he had himself so sane a mind and a heart so kindly, even to his enemies, that it was hard for him to believe in a political hatred so deadly as to lead to murder.” He routinely disregarded such warnings, recalled Nettie Colburn, another medium who visited the White House.

When Booth shot Lincoln on April 14, 1865, at Ford’s Theatre, the search for the assassin and his accomplices commenced immediately. Col. Henry H. Wells, a top military policeman, went to the National Hotel to look for information about the actor. Bunker, the room clerk, told him about Booth’s association with Colchester and said the medium had been staying at the Washington House hotel. But Wells couldn’t find Colchester at the Washington, nor anywhere else in the city. Like the spirits he summoned, Colchester had disappeared.

Related Reads

Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth