The Triumph of Frank Lloyd Wright

The Guggenheim Museum, turning 50 this year, showcases the trailblazer’s mission to elevate American society through architecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/The-Guggenheim-Museum-New-York-631.jpg)

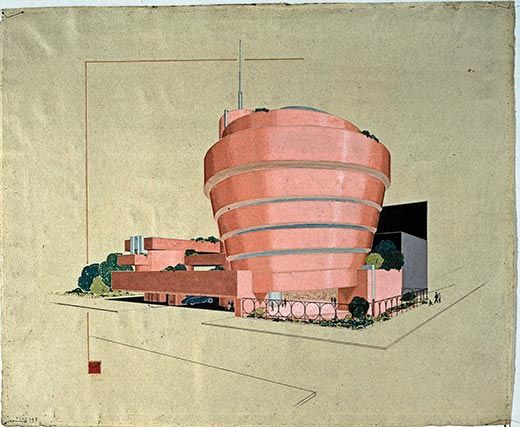

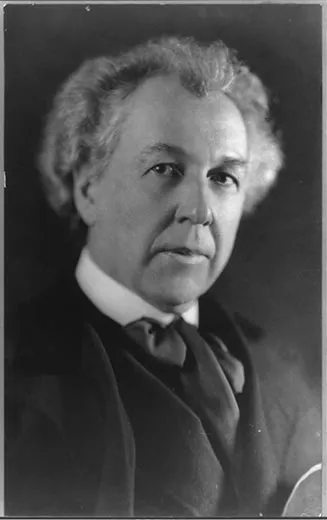

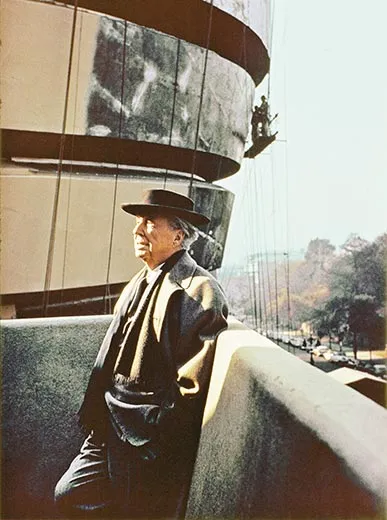

Frank Lloyd Wright's most iconic building was also one of his last. The reinforced-concrete spiral known as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened in New York City 50 years ago, on October 21, 1959; six months before, Wright died at the age of 92. He had devoted 16 years to the project, facing down opposition from a budget-conscious client, building-code sticklers and, most significantly, artists who doubted that paintings could be displayed properly on a slanting spiral ramp. "No, it is not to subjugate the paintings to the building that I conceived this plan," Wright wrote to Harry Guggenheim, a Thoroughbred horse breeder and founder of Newsday who, as the benefactor's nephew, took over the project after Solomon's death. "On the contrary, it was to make the building and the painting a beautiful symphony such as never existed in the world of Art before."

The grandiloquent tone and unwavering self-assurance are as much Wright trademarks as the building's unbroken and open space. Time has indeed shown the Guggenheim's tilted walls and continuous ramp to be an awkward place to hang paintings, yet the years have also confirmed that in designing a building that bestowed brand-name recognition on a museum, Wright was prophetic. Four decades later, Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Bilbao—the curvaceous, titanium-clad affiliated museum in northern Spain—would launch a wave of cutting-edge architectural schemes for art institutions across the globe. But Wright was there first. A retrospective exhibition at the original Guggenheim (until August 23) reveals how often Wright pioneered trends that other architects would later embrace. Passive solar heating, open-plan offices, multi-storied hotel atriums—all are now common, but at the time Wright designed them they were revolutionary.

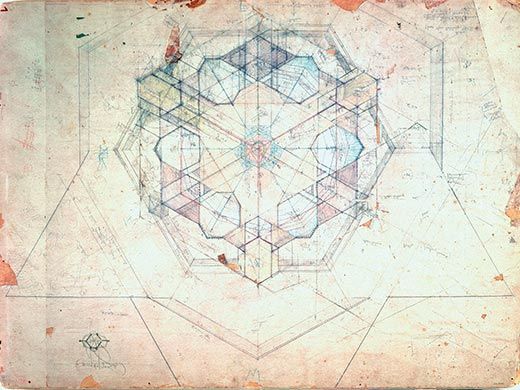

When Solomon Guggenheim, the heir to a mining fortune, and his art adviser, Hilla Rebay, decided to construct a museum for abstract painting (which they called "non-objective art"), Wright was a natural choice as architect. In Rebay's words, the two were seeking "a temple of spirit, a monument" and Wright, through his long career, was a builder of temples and monuments. These included actual places of worship, such as Unity Temple (1905-8) for a Unitarian congregation in Oak Park, Illinois, one of the early masterpieces that proclaimed Wright's genius, and Beth Sholom Synagogue (1953-59) in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, which, like the Guggenheim, he supervised at the end of his life. But in everything he undertook, the goal of enhancing and elevating the human experience was always on Wright's mind. In his religious buildings, he used many of the same devices—bold geometric forms, uninterrupted public spaces and oblique-angled seating—as in his secular ones. The large communal room with overhead lighting that is the centerpiece of Unity Temple was an idea he had introduced in the Larkin Company Administration Building (1902-6), a mail-order house in Buffalo, New York. And before it reappeared in Beth Sholom, what he called "reflex-angle seating"—in which the audience fanned out at 30-degree angles around a projecting stage—was an organizing principle in his theater plans, starting in the early 1930s. To Wright's way of thinking, any building, if properly designed, could be a temple.

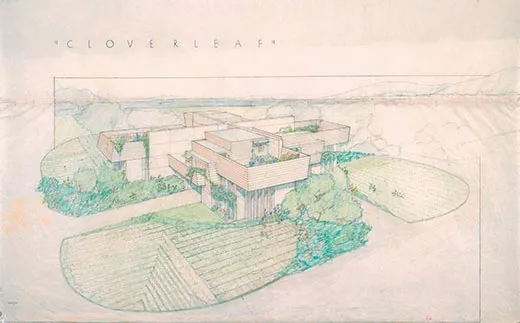

In his unshakable optimism, messianic zeal and pragmatic resilience, Wright was quintessentially American. A central theme that pervades his architecture is a recurrent question in American culture: How do you balance the need for individual privacy with the attraction of community activity? Everyone craves periods of solitude, but in Wright's view, a human being develops fully only as a social creature. In that context, angled seating allowed audience members to concentrate on the stage and simultaneously function as part of the larger group. Similarly, a Wright house contained, along with private bedrooms and baths, an emphasis on unbroken communal spaces—a living room that flowed into a kitchen, for example—unknown in domestic residences when he began his practice in the Victorian era. As early as 1903, given the opportunity to lay out a neighborhood (in Oak Park, which was never built), Wright proposed a "quadruple block plan" that placed an identical brick house on each corner of a block; he shielded the inhabitants from the public street with a low wall and oriented them inward toward connected gardens that encouraged exchanges with their neighbors. Good architecture, Wright wrote in a 1908 essay, should promote the democratic ideal of "the highest possible expression of the individual as a unit not inconsistent with a harmonious whole."

That vision animates the Guggenheim Museum. In the course of descending the building's spiral ramp, a visitor can focus on works of art without losing awareness of other museumgoers above and below. To that bifocal consciousness, the Guggenheim adds a novel element: a sense of passing time. "The strange thing about the ramp—I always feel I am in a space-time continuum, because I see where I've been and where I'm going," says Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archives in Scottsdale, Arizona. As Wright approached the end of his life, that perception of continuity—recalling where he had been while advancing into the future—must have appealed to him. And, looking back, he would have seen telling examples in his personal history of the tension between the individual and the community, between private desires and social expectations.

Wright's father, William, was a restless, chronically dissatisfied Protestant minister and organist who moved the family, which included Wright's two younger sisters, from town to town until he obtained a divorce in 1885 and took off for good. Wright, who was 17 at the time, never saw his father again. His mother's family, the combative Lloyd Joneses, were Welsh immigrants who became prominent citizens of an agricultural valley near the village of Hillside, Wisconsin. Wright himself might have written the family motto: "Truth Against the World." Encouraged by his maternal relatives, Wright showed an early aptitude for architecture; he made his initial forays into building design by working on a chapel, a school and two houses in Hillside, before apprenticing in Chicago with the celebrated architect Louis H. Sullivan. Sullivan's specialty was office buildings, including classic skyscrapers, such as the Carson Pirie Scott & Company building, which were transforming the Chicago skyline.

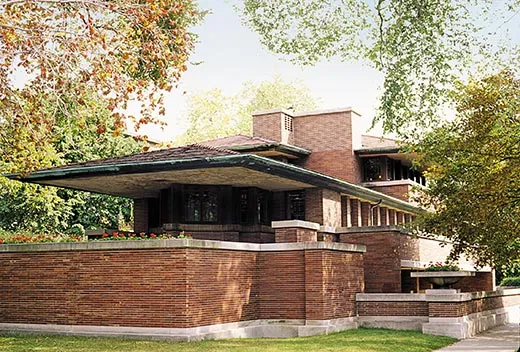

But Wright devoted himself primarily to private residences, developing what he called "Prairie Style" houses, mostly in Oak Park, the Chicago suburb in which he established his own home. Low-slung, earth-hugging buildings with strong horizontal lines and open circulation through the public rooms, they were stripped clean of unnecessary decoration and used machine-made components. The Prairie Style revolutionized home design by responding to the domestic needs and tastes of modern families. Wright had firsthand knowledge of their requirements: in 1889, at 21, he had married Catherine Lee Tobin, 18, the daughter of a Chicago businessman, and, in short order, fathered six children.

Like his own father, however, Wright exhibited a deep ambivalence toward family life. "I hated the sound of the word papa," he wrote in his 1932 autobiography. Dissatisfaction with domesticity predisposed him toward a similarly discontented Oak Park neighbor: Mamah Cheney, a client's wife, whose career as head librarian in Port Huron, Michigan, had been thwarted by marriage and who found the duties of wife and mother a poor substitute. The Wrights and Cheneys socialized as a foursome, until, as Wright later described it, "the thing happened that has happened to men and women since time began—the inevitable." In June 1909, Mamah Cheney told her husband that she was leaving him; she joined Wright in Germany, where he was preparing a book on his work. The scandal titillated newspapers—the Chicago Tribune quoted Catherine as saying she had been the victim of a "vampire" seductress. Wright was painfully conflicted about walking out on his wife and children. He attempted a reconciliation with Catherine in 1910, but then resolved to live with Cheney, whose own work—a translation of the writings of Swedish feminist Ellen Key—provided intellectual support for this convention-defying step. Leaving the Oak Park gossipmongers behind, the couple retreated to the Wisconsin valley of the Lloyd Joneses to start anew.

Just below the crest of a hill in Spring Green, Wright designed a secluded house he called "Taliesin," or "shining brow," after a Welsh bard of that name. A rambling dwelling made of local limestone, Taliesin was the culmination of the Prairie Style, a big house with long roofs extending over the walls. By all accounts, Wright and Cheney lived there happily for three years, slowly winning over neighbors who had been prejudiced by the publicity that preceded them—until Taliesin became the setting for the greatest tragedy of the architect's long and eventful life. On August 15, 1914, while Wright was in Chicago on business, a deranged young cook locked the dining room and set it ablaze, standing with a hatchet at the only exit to bar all inside from leaving. Cheney and her two visiting children were among the seven who died. On the anguished journey to Wisconsin, a devastated Wright and his son John shared a train car with Cheney's former husband. Wright immediately vowed to rebuild the house, which was mostly in ruins. But he never fully recovered emotionally. "Something in him died with her, something loveable and gentle," his son later wrote in a memoir. (In April 1925, as the result of defective wiring, the second Taliesin also suffered a calamitous fire; it would be replaced by a third.)

Wright's domestic life took another turn when a condolence letter from a wealthy divorcée, the determinedly artistic Miriam Noel, led to a meeting and—less than six months after Cheney's death—to an invitation for Noel to come live with Wright at Taliesin. With her financial help, he reconstructed the damaged house. But Taliesin II did not become the sanctuary he sought. Wright was a theatrical personality, with a penchant for flowing hair, Norfolk jackets and low-hanging neckties. Yet even by his standards, the needy Noel was flamboyantly attention-seeking. Jealous of his devotion to Cheney's memory, she staged noisy altercations, leading to an angry separation only nine months after they met. Although the split appeared to be final, in November 1922, Wright obtained a divorce from Catherine and married Noel a year later. But wedlock only exacerbated their problems. Five months after the wedding, Noel left him, opening an exchange of ugly accusations and countercharges in a divorce proceeding that would drag on for years.

During this tempestuous period, Wright had worked on just a few major projects: the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, the Midway Gardens pleasure park in Chicago, and Taliesin. All three were expansions and refinements of work he had done previously rather than new directions. From 1915 to 1925, Wright executed only 29 commissions, a drastic drop-off from the output of his youth when, between 1901 and 1909, he built 90 of 135 commissions. In 1932, in their influential Museum of Modern Art exhibition on the "International Style" in architecture, Philip Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock listed Wright among the "older generation" of architects. Indeed, by this time Wright had been a force in American architecture for more than three decades and was devoting most of his time to giving lectures and publishing essays; it was easy to believe that his best years were behind him. But in fact, many of his most heralded works were still to come.

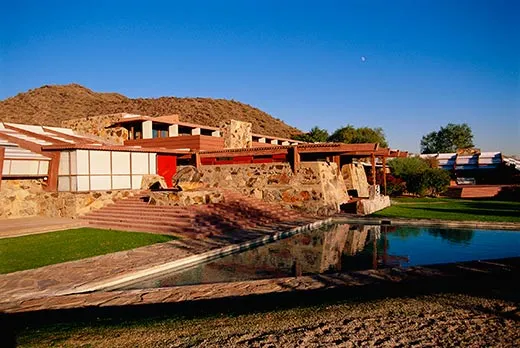

On November 30, 1924, attending a ballet in Chicago, Wright had noticed a young woman seated next to him. "I secretly observed her aristocratic bearing, no hat, her dark hair parted in the middle and smoothed over her ears, a light small shawl over her shoulders, little or no makeup, very simply dressed," he wrote in his autobiography. Wright "instantly liked her looks." For her part, 26-year-old Olgivanna Lazovich Hinzenberg, a Montenegrin educated in Russia, had come to Chicago to try to salvage her marriage to a Russian architect, with whom she had had a daughter, Svetlana. Even before taking her seat, she would recall in an unpublished memoir, she had noticed "a strikingly handsome, noble head with a crown of wavy grey hair." Upon discovering that the ticket she had purchased at the last minute seated her next to this poetic-looking man, her "heart beat fast." During the performance, he turned to her and said, "Don't you think that these dancers and the dances are dead?" She nodded in agreement. "And he smiled, looking at me with unconcealed admiration," she recalled. "I knew then that this was to be." In February 1925, Hinzenberg moved into Taliesin II, where they both waited for their divorces to become final. On the very night in 1925 that Taliesin II burned, she told him that she was pregnant with their child, a daughter they would name Iovanna. They wed on August 25, 1928, and lived together for the rest of Wright's life. The rebuilt Taliesin III would be home to Svetlana and Iovanna—and, in a broader sense, to a community of students and young architects that, beginning in 1932, the Wrights invited to come live and work with them as the Taliesin Fellowship. After Wright suffered a spell of pneumonia in 1936, the community expanded to a wintertime settlement he designed in Scottsdale, Arizona, on the outskirts of Phoenix. He dubbed it Taliesin West.

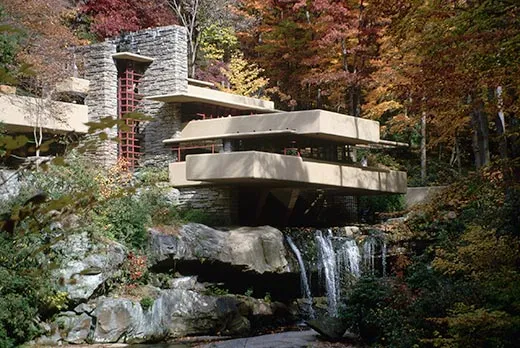

In the last quarter-century of his life, Wright pushed his ideas as far as he could. The cantilevering that he had employed for the exaggeratedly horizontal roofs of the Prairie Style houses assumed a new grandeur in Fallingwater (1934-37), the country house for Pittsburgh department-store owner Edgar Kaufmann Sr., which Wright composed of broad planes of concrete terraces and flat roofs, and—in a stroke of panache—he perched over a waterfall in western Pennsylvania. (Like many Wright buildings, Fallingwater has better stood the test of time aesthetically than physically. It required an $11.5 million renovation, completed in 2003, to correct its sagging cantilevers, leaking roofs and terraces, and interior mildew infestation.) While designing Fallingwater, Wright also transformed the skylit open clerical space of the early Larkin Building into the Great Workroom of the Johnson Wax Company Administration Building (1936) in Racine, Wisconsin, with its graceful columns that, modeled on lily pads, spread to support disks with overhead skylights of Pyrex glass tubing.

Wright's ambition to elevate American society through architecture grew exponentially from the quadruple block plan in Oak Park to the scheme for Broadacre City—a proposal in the 1930s for a sprawling, low-rise development that would roll out a patchwork of houses, farms and businesses, connected by highways and monorails, across the American landscape. His desire to provide affordable, individualized homes that met the needs of middle-class Americans found its ultimate expression in the "Usonian" houses he introduced in 1937 and continued to develop afterward: customizable homes that were positioned on their sites to capture winter sun for passive solar heating and outfitted with eaves to provide summer shade; constructed with glass, brick and wood that made surface decoration such as paint or wallpaper superfluous; lit by clerestory windows beneath the roofline and by built-in electric fixtures; shielded from the street to afford privacy; and supplemented with an open carport, in deference to the means of transportation that could ultimately decentralize cities. "I don't build a house without predicting the end of the present social order," Wright said in 1938. "Every building is a missionary."

His use of "missionary" was revealing. Wright said that his architecture always aimed to serve the client's needs. But he relied on his own assessment of those needs. Speaking of residential clients, he once said, "It's their duty to understand, to appreciate, and conform insofar as possible to the idea of the house." Toward the end of his life, he constructed his second and last skyscraper, the 19-story H. C. Price Company Office Tower (1952-56) in Bartlesville, Oklahoma. After it was completed, Wright appeared with his client at a convocation in town. "A person in the audience asked the question, ‘What's your first prerequisite?'" archivist Pfeiffer recalled. "Mr. Wright said, ‘Well, to fulfill a client's wishes.' To which Price said, ‘I wanted a three-story building.' Mr. Wright said, ‘You didn't know what you wanted.'"

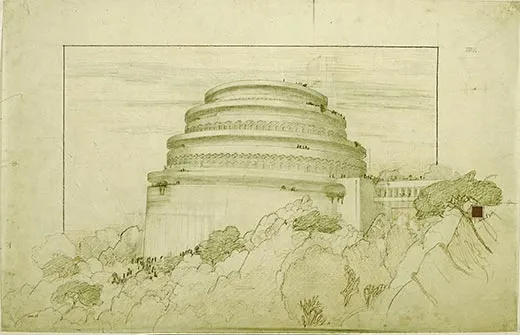

In developing the Guggenheim Museum, Wright exercised his usual latitude in interpreting the client's wishes as well as his equally typical flair for high-flown comparisons. He described the form he came up with as an "inverted ziggurat," which nicely linked it to the temples in the Mesopotamian Cradle of Civilization. In fact, the Guggenheim traced its immediate lineage to an unbuilt Wright project that the architect based on the typology of a parking garage—a spiral ramp he designed in 1924 for the mountaintop Gordon Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium. Wright envisioned visitors driving their cars up an exterior ramp and handing them over to valets for conveyance to the bottom. They could then walk down a pedestrian ramp, admiring the landscape before reaching the planetarium at ground level. "I have found it hard to look a snail in the face since I stole the idea of his house—from his back," Wright wrote to Strong, after the Chicago businessman expressed dissatisfaction with the plans. "The spiral is so natural and organic a form for whatever would ascend that I did not see why it should not be played upon and made equally available for descent at one and the same time." Yet Wright also admitted admiration for the industrial designs of Albert Kahn—a Detroit-based architect whose reinforced-concrete, ramped parking garages foreshadowed both the Strong Automobile Objective and the Guggenheim.

In the long negotiations over costs and safety-code stipulations that protracted the construction of the museum, Wright was forced to compromise. "Architecture, may it please the court, is the welding of imagination and common sense into a restraint upon specialists, codes and fools," he wrote in a draft cover letter for an application to the Board of Standards and Appeals. (At the urging of Harry Guggenheim, he omitted the word "fools.") One sacrificed feature was an unconventional glass elevator that would have whisked visitors to the summit, from which they would then descend on foot. Instead, the museum has had to get by with a prosaic elevator far too small to cope with the attending crowds; as a result, most visitors survey an exhibition while ascending the ramp. Curators typically arrange their shows with that in mind. "You cannot get enough people into that tiny elevator," says David van der Leer, an assistant curator of architecture and design, who worked on the Wright exhibition. "The building is so much more heavily trafficked these days that you would need an elevator in the central void to do that."

Installation of the Wright retrospective brought into high relief the discrepancies between the building's symbolic power and its functional capabilities. For instance, to display Wright's drawings—an unparalleled assortment, which for conservation reasons will not be on view again for at least a decade—the curators placed a mesh fabric "shower cap" on the overhead dome to weaken the light, which otherwise would cause the colors on the paper drawings to fade. "On the one hand, you want to display the building as well as possible, and on the other, you need to show the drawings," van der Leer explains.

The Guggenheim emerged last year from a $28 million, four-year restoration, during which cracks and water damage in the concrete were patched, and the peeling exterior paint (10 to 12 layers' worth) was removed and replaced. Wright buildings are notorious for their maintenance difficulties. During Wright's lifetime, the problems were aggravated by the architect's expressed indifference. One famous story recounts an outraged phone call made by Herbert Johnson, an important Wright client, to report that at a dinner party in his new house, water from a leaky roof was dripping on his head. Wright suggested he move his chair.

Still, when you consider that in many projects the architect designed every element, down to the furniture and light fixtures, his bloopers are understandable. Proudly describing the Larkin Building, Wright said, many years after it opened, "I was a real Leonardo da Vinci when I built that building, everything in it was my invention." Because he was constantly pushing the latest technologies to their utmost, Wright probably resigned himself to the inevitable shortfalls that accompany experimentation. "Wright remained throughout his life the romantic he had been since childhood," historian William Cronon wrote in 1994. "As such, he brought a romantic's vision and a romantic's scale of values to the practical challenges of his life." If the architect seemed not to take the glitches in his built projects too seriously, it may be that his mind was elsewhere. "Every time I go into that building, it is such an uplifting of the human spirit," says Pfeiffer, who probably is the best living guide to Wright's thinking about the Guggenheim. The museum is often said by architectural critics to constitute the apotheosis of Wright's lifelong desire to make space fluid and continuous. But it represents something else as well. By inverting the ziggurat so that the top keeps getting wider, Wright said he was inventing a form of "pure optimism." Even in his 90s, he kept his mind open to expanding possibilities.

Arthur Lubow wrote about the 17th-century Italian sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the October 2008 issue.