The Unknown Story of “The Black Cyclone,” the Cycling Champion Who Broke the Color Barrier

Major Taylor had to brave more than the competition to become one of the most acclaimed cyclists of the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120912114040major-taylor-small.jpg)

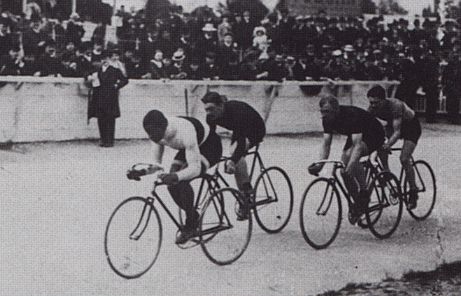

At the dawn of the 20th century, cycling was the most popular sport in both America and Europe, with tens of thousands of spectators drawn to arenas and velodromes to see highly dangerous and even deadly affairs that bore little semblance to bicycle racing today. In brutal six-day races of endurance, well-paid competitors often turned to cocaine, strychnine and nitroglycerine for stimulation and suffered from sleep deprivation, delusions and hallucinations along with falls from their bicycles. In motor-paced racing, cyclists would draft behind motorcycles, reaching speeds of 60 miles per hour on cement-banked tracks, where blown bicycle tires routinely led to spectacular crashes and deaths.

Yet one of the first sports superstars emerged from this curious and sordid world. Marshall W. Taylor was just a teenager when he turned professional and began winning races on the world stage, and President Theodore Roosevelt became one of his greatest admirers. But it was not Taylor’s youth that cycling fans first noticed when he edged his wheels to the starting line. Nicknamed “the Black Cyclone,” he would burst to fame as the world champion of his sport almost a decade before the African-American heavyweight Jack Johnson won his world title. And as with Johnson, Taylor’s crossing of the color line was not without complication, especially in the United States, where he often had no choice but to ride ahead of his white competitors to avoid being pulled or jostled from his bicycle at high speeds.

Taylor was born into poverty in Indianapolis in 1878, one of eight children in his family. His father, Gilbert, the son of a Kentucky slave, fought for the Union in the Civil War and then worked as a coachman for the Southards, a well-to-do family in Indiana. Young Marshall often accompanied his father to work to help exercise some of the horses, and he became close friends with Dan Southard, the son of his father’s employer. By the time Marshall was 8, the Southards had for all intents and purposes adopted him into their home, where he was educated by private tutors and virtually lived the same life of privilege as his friend Dan.

When Marshall was about 13, the Southards moved to Chicago. Marshall’s mother “could not bear the idea of parting with me,” he would write in his autobiography. Instead, “I was dropped from the happy life of a ‘millionaire kid’ to that of a common errand boy, all within a few weeks.”

Aside from the education, the Southards also gave Taylor a bicycle, and the young man was soon earning money as a paperboy, delivering newspapers and riding barefoot for miles a day. In his spare time, he practiced tricks and caught the attention of someone at the Hay and Willits bicycle shop, which paid Marshall to hang around the front of the store, dressed in a military uniform, doing trick mounts and stunts to attract business. A new bicycle and a raise enabled Marshall to quit delivering newspapers and work for the shop full-time. His uniform won him the nickname “Major,” which stuck.

To further promote the store, one of the shop’s owners, Tom Hay, entered Taylor in a ten-mile bicycle race—something the cyclist had never seen before. “I know you can’t go the full distance,” Hay whispered to the terrified entrant, “but just ride up the road a little way, it will please the crowd, and you can come back as soon as you get tired.”

The crack of a starter’s pistol signaled the beginning of an unprecedented career in bicycle racing. Major Taylor pushed his legs beyond anything he’d imagined himself capable of and finished six seconds ahead of anyone else. There he “collapsed and fell in a heap in the roadway,” he wrote, but he soon had a gold medal pinned to his chest. He began competing in races across the Midwest; while he was still 13, his cycling prowess earned him a notice in the New York Times, which made no mention of his youth.

By the 1890s, America was experiencing a bicycle boom, and Taylor continued to work for Hay and Willits, mostly giving riding lessons. While white promoters allowed him to compete in trick riding competitions and races, Taylor was kept from joining any of the local riding clubs, and many white cyclists were less than welcoming to the black phenom. In August 1896, Taylor’s friend and new mentor, Louis D. “Berdi” Munger, who owned the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company in Massachusetts, signed him up for an event and smuggled him into the whites-only races at the Capital City Cycling Club in Indianapolis. He couldn’t officially compete against the professionals, but his time could certainly be measured.

Some of the other riders were friendly with Taylor and had no problems pacing him on tandem bicycles for a time trial. In his first heat, he knocked more than eight seconds off the mile track record, with the crowd roaring when they learned of his time. After a rest, he came back on to the track to see what he could do in the one-fifth-mile race. The crowd tensed as Taylor reached the starting line. Stopwatches were pulled from pockets. He exploded around the track and, at age 17, knocked two-fifths of a second off the world record held by professional racer Ray MacDonald. Taylor’s time could not be turned in for official recognition, but everyone in attendance knew what they had seen. Major Taylor was a force on two wheels.

Marshall “Major” Taylor in 1900. Photo: Wikipedia

Still, Munger’s stunt angered many local cycling officials, and his rider was quickly banned from that Indianapolis track. By that point, it didn’t matter; Taylor was on his way. Later in 1896, he finished eighth in his first six-day race at New York’s Madison Square Garden, even though the hallucinations got to him; at one point he said, “I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand.”

Munger, keen to establish his own racing team with the Black Cyclone as its star, took Taylor to Worcester and put him to work for his company. He was in Massachusetts when his mother died in 1898, which led Taylor to seek baptism and become a devoted member of the John Street Baptist Church in Worcester. Before his teenage years ended, Taylor became a professional racer with seven world records to his name. He won 29 of the 49 races he entered, and in 1899, he captured the world championship of cycling. Major Taylor was just the second black athlete to become a world champion, behind Canadian bantamweight George “Little Chocolate” Dixon, who had won his title a decade before.

Taylor’s victory earned him tremendous fame, but he was barred from races in the South, and even when he was allowed to ride, plenty of white competitors either refused to ride with him or worked to jostle or shove him or box him in. Spectators threw ice and nails at him. At the end of a one-miler in Massachusetts, W.E. Backer, who was upset at finishing behind Taylor, rode up behind him afterward and pulled him to the ground. “Becker choked him into a state of insensibility,” the New York Times reported, “and the police were obliged to interfere. It was fully fifteen minutes before Taylor recovered consciousness, and the crowd was very threatening toward Becker.” Becker would be fined $50 for the assault.

It was abundantly clear to Munger and other friends that Taylor would be better off racing in Europe, where some of the strongest riders in the world were competing and where a black athlete could ride without fear of racially motivated violence. His advisers tried to persuade him to leave the United States, but Taylor would have none of it. The prestigious French events held races on Sundays, and Taylor’s religious convictions prevented him from competing on the Sabbath. ”Never on Sundays,” he insisted.

Still, the money to be made overseas was a strong lure, and the European promoters were eager to bring the Black Cyclone to their tracks. Promoters shifted events from Sundays to French national holidays to accommodate the American. In 1902, Taylor finally competed on the European tour and dominated it, winning the majority of races he entered and cementing his reputation as the fastest cyclist in the world. (He also married Daisy Morris that year, and continued to travel. When he and Daisy had a daughter in 1904, they named her Rita Sydney, after the city in Australia where she was born.)

Taylor raced for the rest of the decade, reportedly earning $30,000 a year, making him one of the wealthiest athletes of his day, black or white. But with the advent of the automobile, interest in cycling began to wane. Taylor, feeling the effects of age on his legs, retired in 1910, at age 32. A string of bad investments, coupled with the Wall Street crash in 1929, wiped out all of his earnings. His marriage crumbled, and he became sickly. After six years of writing his autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, he self-published it in 1929 and spent the last years of his life selling the book door-to-door in Chicago. “I felt I had my day,” he wrote, “and a wonderful day it was too.” Yet when he died, in 1932, at the age of 53, his body lay unclaimed in a morgue, and he was buried in a pauper’s grave at the Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Chicago.

When they learned where Major Taylor’s grave site was, some former racing stars and members of the Olde Tymers Athletic Club of the South Wabash Avenue YMCA persuaded Frank Schwinn, owner of the Schwinn Bicycle Company, to pay to have Taylor’s remains exhumed and transferred to a more fitting location—the cemetery’s Memorial Garden of the Good Shepherd. There, a bronze tablet reads:

“Worlds champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way—Without hatred in his heart—An honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete. A credit to his race who always gave out his best—Gone but not forgotten.”

Sources

Books: Andrew Richie, Major Taylor: The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Racer, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. Marshall W. Taylor, Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds, Ayer Co. Pub, 1928. Andrew M. Homan, Life in the Slipstream: The Legend of Bobby Walthour Sr., Potomac Books Inc., 2011. Marlene Targ Brill, Marshall “Major” Taylor: World Champion Bicyclist , 1899-1901, Twenty-First Century Books, 2008.

Articles: “Major Taylor—The World’s Fastest Bicycle Racer,” by Michael Kranish, Boston Globe Sunday Magazine, September 16, 2001. “‘Worcester Whirlwind’ Overcame Bias,” by Lynne Tolman, Telegram & Gazette, July 23, 1995. http://www.majortaylorassociation.org/whirlwind.htm “Draw the Color Line,” Chicago Tribune, April 10, 1898. “Trouble on Taunton’s Track,” New York Times, September 24, 1897. “Taylor Shows the Way,” Chicago Tribune, August 28, 1898.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)