The Vegas Hotspot That Broke All the Rules

America’s first interracial casino helped end segregation on the Strip and proved that the only color that mattered was green

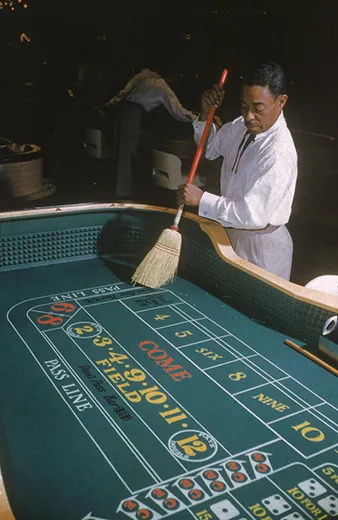

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Moulin-Rouge-Tropi-Can-Can-631.jpg)

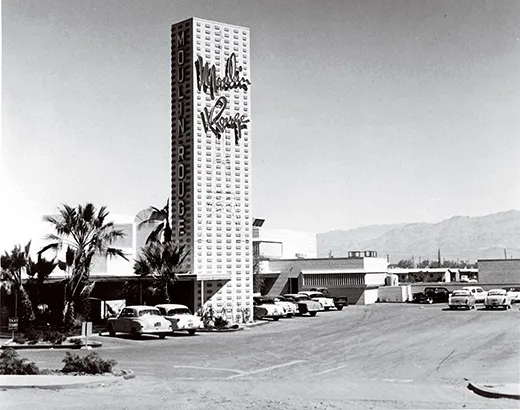

The newest casino in Vegas was a 40-foot trailer in a vacant lot. Inside, gamblers in shorts, T-shirts and baseball caps fed quarters into video-poker machines. Outside, weeds sprouted through the sun-scorched pavement of a forlorn stretch of Bonanza Road near Three Star Auto Body and Didn’tDoIt Bail Bonds. A banner strapped to the trailer announced that this was the “Site of the Famous Moulin Rouge Casino!”

That was the point: Due to one of myriad quirks of Nevada law, some form of gambling must occur here every two years or the owners lose their gaming license. This desolate city block had practically no value except as the site of a hotel-casino that closed more than 50 years ago. And so, last June, workers carried 16 bulky video-poker machines into what locals called a “pop-up casino,” where eight hours of gambling generated a total take of less than $100. Then the workers carted the machines away, padlocked the trailer and left the site of the famous Moulin Rouge to its singing, dancing, wining, dining, hip-shaking, history-making ghosts.

Stan Armstrong, a 56-year-old documentary filmmaker who grew up near the site of the old Moulin Rouge, sees the place as a briefly gleaming facet of the city’s past. “It’s mostly forgotten, even by people who live here, but the Rouge mattered,” he says. “To understand why, you need to know how much this town has changed in 60 years.”

Las Vegas wasn’t much more than a Sin Village in the early 1950s. With a population of 24,000, one twenty-fourth its current total, the city was smaller than Allentown, Pennsylvania, or South Bend, Indiana, and so remote that the Army tested atom bombs an hour’s drive away. Guests on the upper floors of hotels like Binion’s Horseshoe watched the mushroom clouds.

Downstairs, cowboy-hatted Benny Binion, a mobster and convicted murderer from Dallas, lured gamblers to “Glitter Gulch” with a brand-new casino featuring velvet wallpaper and carpeted floors—a step up from the traditional stucco and sawdust. A few miles to the southwest, mobster Bugsy Siegel’s venerable 1946 Flamingo lit up the Strip, as did the Desert Inn, the Sahara and the Sands, all built between 1950 and 1952, all serving prosperous postwar customers who were, not coincidentally, all white.

The town’s black residents occupied a 3.5-square-mile area called the Westside, where dirt streets ran past tents, shanties and outhouses. Jim Crow laws enforced their second-class status. Negroes, as they were printably called, could work at Strip and Glitter Gulch hotels and casinos only as cooks, maids, janitors and porters—“back of the house” jobs that kept their profiles and wages low. Black entertainers were better paid but no more welcome in the front of the house. When Louis Armstrong, Nat King Cole and Ella Fitzgerald headlined on the Strip, they slipped in through stage doors or kitchen doors and left the same way after taking their bows. Unable to rent rooms at whites-only hotels, they retreated to boarding houses on the Westside. Famous or not, they couldn’t try on clothes at white-owned stores. “If you tried something on, they made you buy it,” one Westsider recalls. Another local tells of the day Sammy Davis Jr. took a dip in a whites-only swimming pool at the New Frontier. “Afterward, the manager drained the pool.”

Cole learned his lesson the night a Strip doorman turned him away. “But that’s Nat King Cole,” his white companion said.

“I don’t care if he’s Jesus Christ,” said the doorman. “He’s a n-----, and he stays out.”

Lena Horne was the exception who proved the rule. A favorite of Bugsy Siegel, the gorgeous torch singer was allowed to stay at the Flamingo as long as she steered clear of the casino, restaurants and other public areas. When she checked out, her bedsheets and towels were burned.

In the early ’50s, Josephine Baker, the Missouri-born singer, actress and exotic dancer who achieved worldwide fame for her performances in Paris, appeared at El Rancho on the Strip. As an international sex symbol (Hemingway called her “the most sensational woman anyone ever saw”), the “Creole Goddess” had the power to bend rules in Vegas. Her contract stipulated that black people could buy tickets to her show. As Walter Winchell reported in his New York Daily Mirror gossip column, Baker “won’t appear anywhere members of her race are not admitted.” When El Rancho kept black ticket-buyers out, Baker sat on the stage doing nothing. “I’m not going to entertain,” she said. “I’m going to sit right here until they make up their minds what they want to do.”

Lubertha Johnson was one of the black ticket-holders that night. “Customers were waiting,” she once recalled. “Finally the management let us in and told us to sit down, and they served us.”

***

Then came the Moulin Rouge, in 1955, a neon cathedral dedicated to the proposition that the only color that mattered in Vegas was green.

The Rouge, as locals call it, was the brainchild of several white businessmen led by Los Angeles real-estate baron Alexander Bisno and New York restaurateur Louis Rubin. They spent $3.5 million to build what they billed as “America’s First Interracial Hotel.” The time seemed ripe. President Harry Truman had abolished segregation in the U.S. military in 1948. Six years later, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education did the same for public schools.

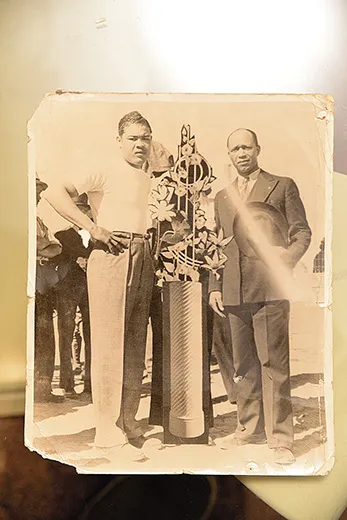

Bisno, Rubin and their partners integrated their project by giving former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis a small ownership share to serve as the Rouge’s greeter, shaking hands at a front door that was open to all. They hired and trained black waiters, waitresses and blackjack dealers. And while their resort rose on the Westside’s eastern edge, barely dice-rolling distance from Glitter Gulch, they dispatched talent scouts to nightclubs in black neighborhoods all over the country, to find “the loveliest, leggiest ladies of their race” for the chorus line.

Dee Dee Jasmin auditioned at the Ebony Showcase Theatre in Los Angeles. Only 16, she had danced in Carmen Jones, the 1954 film starring Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte. During her Carmen Jones audition, director Otto Preminger had pointed at her and said, “I vant the girl with the big boobs!” A year later, Moulin Rouge owner Bisno offered the teenager a contract for a mind-boggling $135 a week. Soon she was flying to Las Vegas, where a limousine waited to carry Jasmin and her fellow dancers to work. “We were dressed to the nines in our gloves and high heels,” she recalls, “expecting bright lights.” As the limo rolled past the Flamingo and the Sands, “we were in awe...and then we kept going. Past the Sahara. Past a block full of run-down buildings and derelicts. Across the railroad tracks. I thought, ‘I’ll be damned, it’s in the black part of town.’ Then we pulled up at the Rouge, this great big palace on Bonanza Road, and our spirits lifted.”

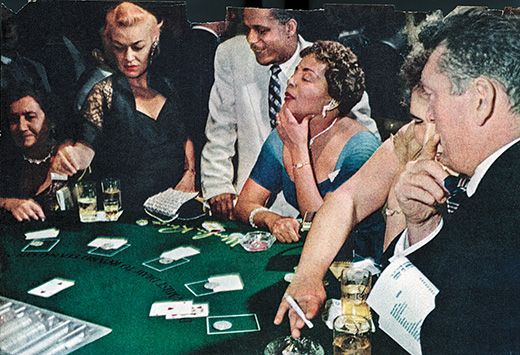

On May 24, 1955, opening night, a well-heeled crowd gathered under a 60-foot sign that read “Moulin Rouge” in white neon. Joe Louis shook hundreds of hands. Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey were playing the New Frontier that week, while Rosemary Clooney and Joey Bishop headlined at the Sands, but for once the real action was on the Westside, where patrons including Belafonte, Tallulah Bankhead and Hollywood tough guy Edward G. Robinson swept into a mahogany-paneled, chandeliered casino. Cigarette girls in frilled dresses and rouge-jacketed waiters served guests looking over the hotel’s palm-lined swimming pool.

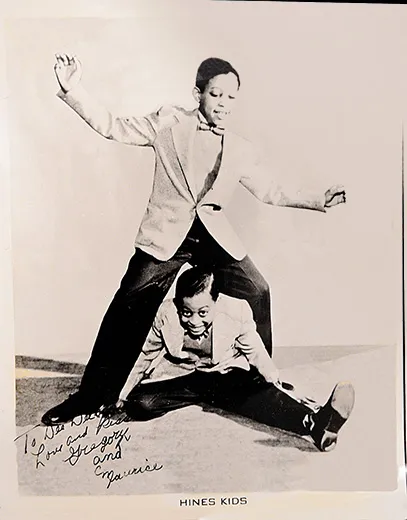

In the showroom, emcee Bob Bailey, a cousin of Pearl’s, introduced the Platters, whose hit song “Only You” would soon top the soul and pop charts. Vaudeville comics Stump and Stumpy gave way to the tap-dancing Hines Kids, 11-year-old Maurice and 9-year-old Gregory. But the floor show carried the night. “We knocked ’em out,” says Jasmin, who recalls looking over the footlights at a house that was “jumping. It was wall-to-wall beautiful people, furs and chiffons and satins and all kinds of jewels. They couldn’t believe what they were seeing.”

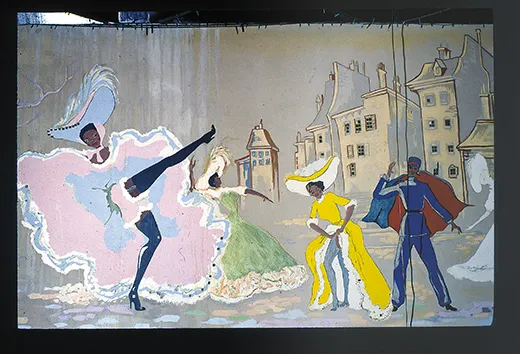

The floor show, produced by Clarence Robinson, a veteran of the Cotton Club and the original Moulin Rouge in Paris, featured a dozen male dancers and 23 chorus girls in the most acrobatic production the city had seen. An opening number called “Mambo City” segued into a strobe-lit dance: the original watusi, in which the now-barefoot, grass-skirted chorus line gyrated to a “jungle beat” while a witch doctor juggled a pair of squawking chickens. The watusi would inspire a nationwide dance fad. Robinson’s performers topped it with a high-kicking finale, the “Tropi Can Can,” that brought the first-night crowd to its feet.

“This isn’t the opening of a Las Vegas hotel. It’s history,” proclaimed Joe Louis.

Emcee Bailey said simply, “That show was a popper!”

Within a month, the Moulin Rouge dancers were doing the “Tropi Can Can” on the cover of Life magazine. Life’s feature story forecast a starry future for “this most modern hostelry.” Cary Grant, Bob Hope, the Dorsey Brothers and Rosemary Clooney dropped in to see what the fuss was about. Variety reported, “This unusual spot continues to pull in the gambling sect, who are not alarmed in the least about rubbing elbows and dice in mixed racial company.”

Rather than the riots some pundits had predicted, everyone got along. A black visitor from the South marveled at seeing interracial couples in the casino at a time when dozens of states, including Nevada, still had miscegenation laws on the books. “Where I come from,” he said, “that’d get you lynched.” Along with eye-popping entertainment, the frisson of racial mixing attracted sellout crowds and Hollywood royalty. Humphrey Bogart, Gregory Peck, Milton Berle, Dorothy Lamour, Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, George Burns and Gracie Allen all came to the Rouge.

One night the dancers were undressing backstage when someone said, “Get your clothes on—it’s Frank!” Frank Sinatra, the biggest star of all, barged in to say how much he loved the show.

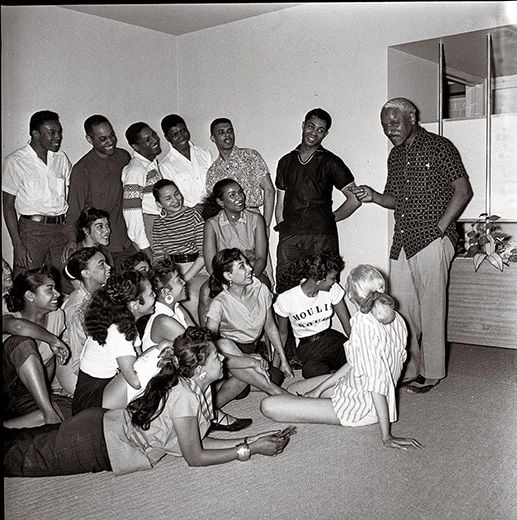

The Moulin Rouge’s luster gained wattage when Sinatra fell under its spell. A night owl who joked that Las Vegas had only one flaw—“There’s nothing to do between 8 and 9 a.m.”—he’d light out for the Rouge after his midnight show at the Sands or Sahara, along with an entourage that at various times included Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford and a disconcerted 70-year-old gossip columnist, Hedda Hopper. As usual, Sinatra’s timing was perfect. The resort’s managers, sensing an opportunity in the predawn hours, began staging a third nightly show beginning at 2:30. That show spurred a series of jam sessions that some say were never equaled in Vegas or anywhere else.

After the third show a relaxed, appreciative Sinatra might join Cole, Louis Armstrong or Dinah Washington on the showroom stage. They’d sing a song or two, and invite other performers to join them: Belafonte, Davis, Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, taking turns or singing together, with no cameras or tape recorders rolling. “Imagine it—the great talents of the time, white and black, jamming and winging it at a time when black entertainers couldn’t set foot in the lounges on the Strip,” says Michael Green, professor of history at the College of Southern Nevada. “Where else was there ever a scene to match that?” When they’d finally worn themselves out, the stars would stub out their last cigarettes and roll east on Bonanza as the sun rose over Glitter Gulch.

Not everyone loved the new action on the Westside. “The Strip’s casino owners couldn’t help noticing the money they were losing to the Moulin Rouge,” Green says. The owners and managers of Strip resorts wanted their customers to gamble after midnight shows, not decamp to the Westside. They gave their showgirls free drinks to stick around after hours, to motivate the gamblers, but as the spring of 1955 boiled into 100-degree summer days, many of the Strip’s white showgirls followed late-night crowds to the Rouge, leaving their home casinos half-empty. Word came down from executive offices on the Strip: Showgirls seen leaving for the Moulin Rouge would be fired. “So they hid in the back seats of cars,” dancer Dee Dee Jasmin recalls, “and partied with us behind the scenes, eating soul food, singing and dancing.”

The Strip remained segregated, but the sea change the Rouge represented was beginning to dissolve racial barriers. In 1955, for the first time, Sammy Davis Jr. was allowed to bring his stepmother and grandmother to see his show in the Venus Room at the New Frontier (where Elvis Presley would make his Las Vegas debut a few months later, singing his number-one hit “Heartbreak Hotel”). Rouge regulars Sinatra and Davis joked onstage about Sammy’s racial situation. “What would happen if some of those ‘priests’ in white robes started chasing you at 60 miles an hour?” Frank asked. “What would you do?” And Sammy answered, “Seventy.”

Belafonte chose that same transformative year, 1955, to integrate the swimming pool at the Riviera. He didn’t ask permission, he just jumped. According to his biographer Arnold Shaw, Belafonte splashed around, watching for security guards, “expecting all hell to break loose.” But nobody shouted or emptied the pool. White guests hurried to their rooms—but only to fetch their cameras. “Before long, mothers and fathers were asking Harry to pose with their youngsters for pictures.”

The Moulin Rouge sold out three shows a night through the summer and early fall. Then, on a crystalline October day in 1955, dancers, waiters, blackjack dealers and cigarette girls reporting to work found padlocks on the doors. America’s only integrated hotel-casino closed after four and a half months in operation. “We were out of work and out of luck,” recalls Jasmin, who says she saw some of the club’s owners leaving with bags of money from the counting room.

***

What killed the Rouge? Jasmin believes her bosses looted the place. Others blame the owners of established resorts, who may have pressed banks to call in loans to their red-hot competitor. Still others blame mobsters bent on proving that they ran the city; or a mid-’50s glut of new hotels that put downward pressure on prices; or even Westside blacks who didn’t gamble enough. “There’s plenty of murk in Las Vegas history,” says Green, the Southern Nevada professor. “In the end I think four factors sank the Moulin Rouge: bad management, bad location, bad timing and bad luck.”

No other resort would hire the Rouge’s black dancers, dealers and other front-of-the-house workers. Some found jobs as maids or dishwashers on the Strip or in the Gulch. Many more left town. The Rouge would reopen for three days between Christmas and New Year’s in 1956 but stood empty the rest of the year. Elsewhere, the civil rights movement was on the march. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus two months after the Rouge closed, spurring a boycott led by a young minister, Martin Luther King Jr. In Las Vegas, headliner Nat King Cole was barred from staying at the Thunderbird despite a deal that paid him $4,500 a week and provided a free suite for his manager, Mort Ruby. “I had to find Nat a place in the dirtiest hole I had ever seen,” Ruby said, “on the other side of the tracks.” Near the shuttered Moulin Rouge.

Dancer Anna Bailey couldn’t get work. She had backed up Cab Calloway and the Ink Spots in Harlem, danced with Bill “Bojangles” Robinson in Los Angeles, but no Vegas show-runner would hire her. One night in the late ’50s, she joined a group of black women going to see Sinatra at the Sands. “A security guard stopped us,” Bailey recalled. No blacks allowed, the guard said. “And Frank Sinatra came and got us at the door. He walked us into the lounge and sat us down at his table. Sammy Davis Jr. had his head down, he was so embarrassed by what happened to us. I was just so proud, walking behind Frank Sinatra and sitting down to his table!”

In March 1960, Westsiders including James McMillan and Charles West, the state’s first black dentist and physician, respectively, demanded a meeting with civic leaders. They threatened a mass march: hundreds of blacks chanting and waving placards on the Strip, demanding their rights, threatening to disrupt business. McMillan and West were probably bluffing. They could have counted on no more than a few dozen marchers. Still the mayor, Oran Gragson, the police chief, the county sheriff, resort industry bosses, the Las Vegas Sun publisher Hank Greenspun and Nevada Gov. Grant Sawyer agreed to meet them—in the coffee shop at the Moulin Rouge. “Everyone had their say. Then the governor said it was right to protest the conduct of the Strip,” recalled a member of McMillan and West’s contingent. “He felt that every man should have an equal opportunity.” Under a pact known as the Moulin Rouge Agreement, official segregation ended at 6 p.m. that day.

Soon Anna Bailey became the first black chorus girl on the Strip.

“Since then we’ve had no racial problems,” says Claytee White, director of the Oral History Research Center at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “I’m joking!” White notes that when Governor Sawyer named former Moulin Rouge emcee Bob Bailey to a state commission investigating racial bias in 1961, “Bob didn’t have to search too hard.” Hotels in the state capital, Carson City, refused to serve blacks, so commissioner Bailey packed box lunches and changed clothes in a men’s room in the Capitol building.

The Rouge stood for another 48 years, serving as a motel, a public-housing apartment complex, and finally a glorified flophouse infested with rats, roaches and drug dealers. It made the National Register of Historic Places in 1992, but by then—and ever since—the corner of Bonanza and H Street seemed cursed. “Developers and preservationists kept trying to save it,” recalls Oscar Goodman, Las Vegas’ mayor from 1999 to 2011. “I must have gone to 17 groundbreakings there. I did more groundbreakings at the Moulin Rouge than anywhere else in the city, but that lot’s still sitting there empty.”

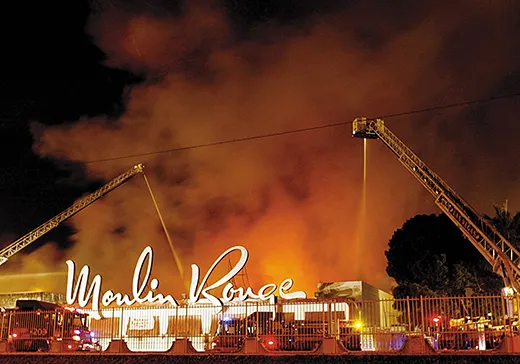

A 2003 arson fire gutted the place, charring a shipment of commemorative T-shirts made by a group that planned to rebuild the hotel. Figuring that the torched tees would make unforgettable souvenirs, the investors sent them to a picture-framing shop to have them mounted under glass. The shop promptly burned down.

Another fire destroyed the remains of the crumbling edifice in 2009. The timing of the incident—less than a week after the Rouge’s famed neon sign was trucked to a museum—had locals retelling an old joke about the mobbed-up lawyer who joins the fire chief at a three-alarm blaze and says, “Chief, the fire’s supposed to be tomorrow.” But the only people who seemed to gain from the last fire on the old lot were the hard hats who bulldozed the ruins.

***

Filmmaker Armstrong grew up on the Westside, where the empty Moulin Rouge cast a long shadow every morning. Born the year after the Rouge closed, Armstrong has spent three years documenting its history. Last fall, screening a cut of his upcoming documentary, The Misunderstood Legend of the Las Vegas Moulin Rouge, he smiled at a shot of the crowd lined up outside the casino on opening night.

“What a night!” he said. “I wish I could have been there. But it couldn’t last. It’s a shame it closed, but what was the future for the ‘First Interracial Hotel’? Integration would have killed it in the ’60s anyway, because who needs an interracial hotel on the wrong side of the tracks once the Sands and the Trop are integrated?”

On a recent visit to the flattened National Historic Site, Armstrong kicked a pebble past the weedy spot where Joe Louis greeted opening-night guests in 1955. The Westside is still mostly African-American, but without the Rouge and other local businesses that thrived in the ’50s, the neighborhood is quieter, more desolate than ever. This vacant lot’s gaming license was still in order on the day of his visit, thanks to last year’s eight-hour reappearance of the pop-up casino, but Armstrong didn’t expect the Rouge to rise again. He was sure the latest plans to rebuild it would come to nothing. Comparing the site to Camelot, he said, “In its one shining moment, the Moulin Rouge brought pride to black Las Vegas. Pride and hope. In that moment, the Rouge changed the world. And then the world moved on.”