The Vice Presidents That History Forgot

The U.S. vice presidency has been filled by a rogues gallery of mediocrities, criminals and even corpses

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/History-Veeps-Dan-Quayle-631.jpg)

In 1966, I stood outside my elementary school in Maryland, waving a sign for Spiro Agnew. He was running for governor against a segregationist who campaigned on the slogan, “Your Home Is Your Castle—Protect It.” My parents, like many Democrats, crossed party lines that year to help elect Agnew. Two years later, he became Richard Nixon’s surprise choice as running mate, prompting pundits to wonder, “Spiro who?” At 10, I was proud to know the answer.

Agnew isn’t otherwise a source of much pride. He became “Nixon’s Nixon,” an acid-tongued hatchet man who resigned a year before his boss, for taking bribes. But “Spiro who?” turned me into an early and enduring student of vice-presidential trivia. Which led me, a few months ago, to Huntington, Indiana, an industrial town that was never much and is even less today. It’s also the boyhood home of our 44th vice president.

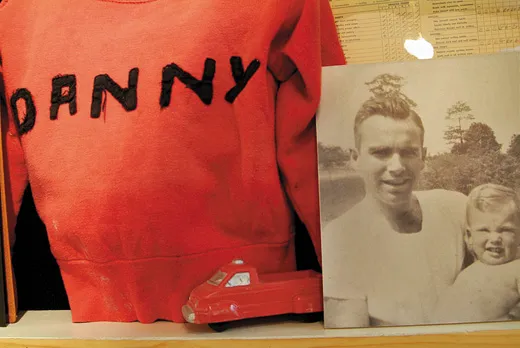

His elementary school is unmarked, a plain brick building that’s now a senior citizens center. But across the street stands an imposing church that has been rechristened the “Quayle Vice Presidential Learning Center.” Inside the former chapel, you can see “Danny” Quayle’s report card (A’s and B’s), his toy truck and exhibits on his checkered tenure as vice president. He “accomplished more than most realize,” a caption states, noting Quayle’s visits to 47 countries and his chairmanship of the Council on Competitiveness.

But the learning center isn’t a shrine to Quayle—or a joke on its namesake, who famously misspelled “potato.” It is, instead, a nonpartisan collection of stories and artifacts relating to all 47 vice presidents: the only museum in the land devoted to the nation’s second-highest office. This neglect might seem surprising, until you tour the museum and learn just how ignored and reviled the vice presidency has been for most of its history. John Nance Garner, for one, said the job wasn’t worth a bucket of warm spit.

“Actually, Garner said ‘piss,’ not spit, but the press substituted another warm bodily fluid,” notes Daniel Johns, the museum director. This polishing of Garner’s words marked a rare instance of varnish being applied to the office. While Americans sanctify the presidency and swathe it in myth, the same has rarely applied to the president’s “spare tire,” as Garner also called himself.

“Ridicule is an occupational hazard of the job,” Johns observes, leading me past political cartoons, newspaper invective and portraits of whiskered figures so forgotten that the museum has struggled to find anything to say or display about them. He pauses before a group portrait of Indiana’s five VPs, a number that stirs Hoosier pride—except that the first, Schuyler Colfax, took bribes in a railroad scandal and died unrecognized on a railroad platform.

“His picture should be hung a little more crooked,” Johns quips. He moves on to Colfax’s successor, Henry Wilson, who died in office after soaking in a tub. Then comes William Wheeler, unknown even to the man at the top of the ticket in 1876. “Who is Wheeler?” Rutherford B. Hayes wrote upon hearing the quiet congressman suggested as his running mate.

The VP museum, which once used the advertising motto “Second to One,” isn’t kind to the nation’s founders, either. It was they who are largely to blame for the rogues, also-rans and even corpses who have often filled the office. The Constitution gave almost no role to the vice president, apart from casting tie-breaking votes in the Senate. John Adams, the first to hold the job, called it “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived.”

The Constitution also failed to specify the powers and status of vice presidents who assumed the top office. In fact, the second job was such an afterthought that no provision was made for replacing VPs who died or departed before finishing their terms. As a result, the office has been vacant for almost 38 years in the nation’s history.

Until recently, no one much cared. When William R.D. King died in 1853, just 25 days after his swearing-in (last words: “Take the pillow from under my head”), President Pierce gave a speech addressing other matters before concluding “with a brief allusion” to the vice president’s death. Other number-twos were alive but absentee, preferring their own homes or pursuits to an inconsequential role in Washington, where most VPs lived in boardinghouses (they had no official residence until the 1970s). Thomas Jefferson regarded his vice presidency as a “tranquil and unoffending station,” and spent much of it at Monticello. George Dallas (who called his wife “Mrs. Vice”) maintained a lucrative law practice, writing of his official post: “Where is he to go? What has he to do?—no where, nothing.” Daniel Tompkins, a drunken embezzler described as a “degraded sot,” paid so little heed to his duties that Congress docked his salary.

Even more eccentric was Richard Johnson, a Kentucky legislator who once petitioned Congress to send an expedition to drill “the Polar regions,” to determine if the earth was hollow and habitable. He also boasted of being “born in a cane brake and cradled in a sap trough,” and took credit for slaying the Indian chief Tecumseh. This spawned the campaign slogan “Rumpsey Dumpsey, Col. Johnson killed Tecumsey!” It also made the frontier war-hero a ticket-balancing running mate to Martin Van Buren, a dandyish New Yorker accused of wearing corsets.

But Johnson had his own baggage. He took a slave as his common-law wife and escorted his two mulatto daughters to public functions. This enraged Southern congressmen, who almost denied him the vice presidency. Once in office, Johnson succumbed to chronic debts and decamped for Kentucky, where he ran a hotel and tavern and grew so disheveled that an English visitor wrote, “If he should become President, he will be as strange-looking a potentate as ever ruled.”

Johnson never made it, but his successor did. Upon President Harrison’s death in 1841, John Tyler became the first VP to step into the executive breach. Dubbed “His Accidency,” Tyler lived up to his mediocre reputation and became the first president not to run for a second term (no party would have him). The next three VPs to replace dead presidents also failed to win re-election. Millard Fillmore became arguably our most obscure president; Andrew Johnson, “shamefully drunk” at his vice-presidential inauguration, was impeached; and the corpulent Chester Arthur, who served 14-course meals at the White House, was dumped by his own party.

Sitting vice presidents proved disposable, too. During one 62-year stretch, none were nominated for a second chance at the second job. James Sherman broke this streak in 1912, only to die shortly before the election. President Taft didn’t replace him and ran with a dead man on the ticket. The vice presidency, Theodore Roosevelt observed, was “not a steppingstone to anything except oblivion.”

One reason so few VPs distinguished themselves was the mediocrity (or worse) of second-stringers chosen in smoke-filled rooms to pay off party bosses or secure key states like Indiana (only New York has provided more VPs). Another impediment was the office itself, which seemed to diminish even its eminent occupants. Charles Dawes won a Nobel Peace Prize for helping reconstruct Europe after World War I—only to wither as VP to do-nothing Calvin Coolidge. Dawes’ successor, Charles Curtis, was part Kaw Indian and made a remarkable rise from reservation boyhood to Senate majority leader. Then, as Herbert Hoover’s VP, Curtis became a laughingstock, lampooned in a Gershwin musical, feeding peanuts to pigeons and squirrels.

Many presidents made matters worse by ignoring or belittling their understudies. Hoover didn’t mention Curtis in his inaugural address. Adlai Stevenson (the forgotten grandfather of the 1950s liberal of the same name) was once asked if President Cleveland had consulted him about anything of even minor consequence. “Not yet,” he said. “But there are still a few weeks of my term remaining.”

The energetic Teddy Roosevelt feared as VP that he “could not do anything,” and wrote an article urging that the role be expanded. But when he became president upon McKinley’s assassination, and then won re-election with Senator Charles Fairbanks, T.R. did nothing to break the pattern. The fiery Roosevelt disliked Fairbanks, a dour conservative known as “the Indiana Icicle,” and not only scorned the VP but undercut his White House ambitions. Four years after T.R. left office, Fairbanks was again offered a place on the Republican ticket. “My name must not be considered for Vice President,” he replied. “Please withdraw it.”

It wasn’t until the mid-20th century that vice presidents began to emerge as more than a “contingent somebody,” or “nullity” in Washington (the words of Lincoln’s first VP, Hannibal Hamlin, a cardplayer who said the announcement of his candidacy ruined a good hand). As government rapidly expanded during the Depression, Franklin Roosevelt used “Cactus Jack” Garner, a veteran legislator, as his arm-twister in Congress. During World War II, Roosevelt made his second VP, Henry Wallace, a globe-trotting ambassador and head of wartime procurement.

Harry Truman, by contrast, served FDR for only 82 days and wasn’t consulted or prepared for the top job, a deficit he set out to correct as president. His VP, Alben Barkley, joined the National Security Council and cabinet meetings. Truman raised the salary of the office and gave it a seal and flag. Barkley’s tenure also bestowed an enduring nickname on the job. A folksy Kentuckian who disliked the formal “Mr. Vice President,” Barkley took his grandson’s suggestion and added two e’s between the title’s initials. Hence “Veep.”

The status and duties of vice presidents have risen ever since, along with their political fortunes. Four of the past 12 VPs became president; two others, Hubert Humphrey and Al Gore, just missed. In 1988, George H.W. Bush became the first sitting vice president to win election to the top job since Van Buren in 1836. The perks of office have also improved. A century ago, VPs still paid for their own lodging, car repairs and official entertaining. Today, they inhabit a Washington mansion and West Wing office, have large salaries and staffs, and merit their own anthem, “Hail Columbia.”

This road to vice-presidential respectability has, of course, hit bumps. Lyndon Johnson feuded with the Kennedys and their aides, who called him “Uncle Cornpone.” Agnew took kickbacks in his White House office. Nelson Rockefeller, given little but ceremonial duties by President Ford, said of his job: “I go to funerals. I go to earthquakes.” Dick Cheney shot a friend in the face.

Veeps have also struggled to shed their image as lightweights, bench warmers and easy targets of derision. Dan Quayle’s frequent gaffes gave endless fodder to late-night TV hosts, and one of his malapropisms entered Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations: “What a waste it is to lose one’s mind. Or not to have a mind is being very wasteful.” Quayle’s troubles even feature at the learning center named for him in Indiana. The director, Johns, says the museum began as a small “hometown rah-rah exhibit” at a local library. But with Quayle’s encouragement, it grew into a two-story collection focused on the office rather than Huntington’s favorite son. Though Quayle occupies more space than any other VP, the exhibits on him refer to the “potatoe” incident and include a political cartoon of a reporter with a bat, enjoying “Quayle season.”

Johns takes the long view of Quayle’s drubbing by the press, and believes it’s instructive for students who visit his museum. “Quayle took a lot of flak, and that’s pretty much the history of the vice presidency, going back two centuries,” he says. Johns also suggests, half-seriously, that potential VPs be vetted for qualities other than their experience and integrity. Humility and a sense of humor may be equally important prerequisites for the job.

No one grasped this better than Quayle’s fellow Hoosier, Thomas Marshall, whose home lies 20 miles north of Huntington on the “Highway of Vice Presidents,” so-called because three of Indiana’s lived along it. Marshall was a small-town lawyer for most of his career, and his modest clapboard home now houses a museum of county history, with a brick outhouse in the yard. Inside, the exhibits include Marshall’s shaving cup, a “pig stein” given to him by a German diplomat and pictures of him feeding a squirrel at the Capitol. Only one or two people visit each week to see the Marshall items.

“The epitome of the vice president as nonentity,” reads Marshall’s entry in an authoritative Senate history of the office. President Woodrow Wilson was a haughty Princetonian who considered Marshall a “small-caliber man.” Wilson also wrote that a VP’s only significance “consists in the fact that he may cease to be Vice President.”

In Marshall’s case this almost happened, when Wilson suffered a paralytic stroke. But the VP was so out of the loop that he didn’t know the severity of Wilson’s condition until told by a reporter that the president might die. “I never have wanted his shoes,” wrote Marshall, who continued to do little more than entertain foreign dignitaries and throw out the first pitch on opening day.

He did, however, gain a reputation for wit. While listening to a long Senate speech about the nation’s needs, Marshall quipped: “What this country needs is a good five-cent cigar.” He also told a joke about two brothers. “One ran away to sea, the other was elected vice president, and nothing was ever heard of either of them again.”

This proved true of Marshall, who quietly returned to Indiana and wrote a self-deprecating memoir. He didn’t want to work anymore, he said, wryly adding: “I wouldn’t mind being Vice President again.”