The Waldseemüller Map: Charting the New World

Two obscure 16th-century German scholars named the American continent and changed the way people thought about the world

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Waldseemuller-Map-631.jpg)

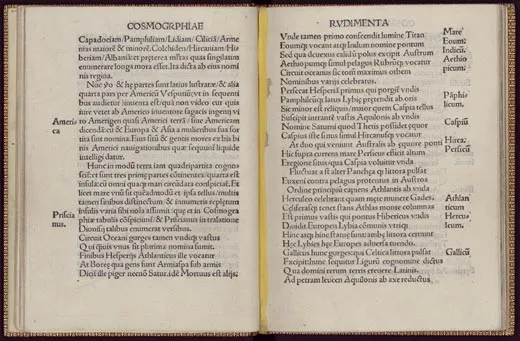

It was a curious little book. When a few copies began resurfacing, in the 18th century, nobody knew what to make of it. One hundred and three pages long and written in Latin, it announced itself on its title page as follows:

INTRODUCTION TO COSMOGRAPHY

WITH CERTAIN PRINCIPLES OF GEOMETRY AND

ASTRONOMY NECESSARY FOR THIS MATTER

ADDITIONALLY, THE FOUR VOYAGES OF

AMERIGO VESPUCCI

A DESCRIPTION OF THE WHOLE WORLD ON BOTH

A GLOBE AND A FLAT SURFACE WITH THE INSERTION

OF THOSE LANDS UNKNOWN TO PTOLEMY

DISCOVERED BY RECENT MEN

The book—known today as the Cosmographiae Introductio, or Introduction to Cosmography—listed no author. But a printer's mark recorded that it had been published in 1507, in St. Dié, a town in eastern France some 60 miles southwest of Strasbourg, in the Vosges Mountains of Lorraine.

The word "cosmography" isn't used much today, but educated readers in 1507 knew what it meant: the study of the known world and its place in the cosmos. The author of the Introduction to Cosmography laid out the organization of the cosmos as it had been described for more than 1,000 years: the Earth sat motionless at the center, surrounded by a set of giant revolving concentric spheres. The Moon, the Sun and the planets each had their own sphere, and beyond them was the firmament, a single sphere studded with all of the stars. Each of these spheres wheeled grandly around the Earth at its own pace, in a never-ending celestial procession.

All of this was delivered in the dry manner of a textbook. But near the end, in a chapter devoted to the makeup of the Earth, the author elbowed his way onto the page and made an oddly personal announcement. It came just after he had introduced readers to Asia, Africa and Europe—the three parts of the world known to Europeans since antiquity. "These parts," he wrote, "have in fact now been more widely explored, and a fourth part has been discovered by Amerigo Vespucci (as will be heard in what follows). Since both Asia and Africa received their names from women, I do not see why anyone should rightly prevent this [new part] from being called Amerigen—the land of Amerigo, as it were—or America, after its discoverer, Americus, a man of perceptive character."

How strange. With no fanfare, near the end of a minor Latin treatise on cosmography, a nameless 16th-century author briefly stepped out of obscurity to give America its name—and then disappeared again.

Those who began studying the book soon noticed something else mysterious. In an easy-to-miss paragraph printed on the back of a foldout diagram, the author wrote, "The purpose of this little book is to write a sort of introduction to the whole world that we have depicted on a globe and on a flat surface. The globe, certainly, I have limited in size. But the map is larger."

Various remarks made in passing throughout the book implied that this map was extraordinary. It had been printed on several sheets, the author noted, suggesting that it was unusually large. It had been based on several sources: a brand-new letter by Amerigo Vespucci (included in the Introduction to Cosmography); the work of the second-century Alexandrian geographer Claudius Ptolemy; and charts of the regions of the western Atlantic newly explored by Vespucci, Columbus and others. Most significant, it depicted the New World in a dramatically new way. "It is found," the author wrote, "to be surrounded on all sides by the ocean."

This was an astonishing statement. Histories of New World discovery have long told us that it was only in 1513—after Vasco Núñez de Balboa had first caught sight of the Pacific by looking west from a mountain peak in Panama—that Europeans began to conceive of the New World as something other than a part of Asia. And it was only after 1520, once Magellan had rounded the tip of South America and sailed into the Pacific, that Europeans were thought to have confirmed the continental nature of the New World. And yet here, in a book published in 1507, were references to a large world map that showed a new, fourth part of the world and called it America.

The references were tantalizing, but for those studying the Introduction to Cosmography in the 19th century, there was an obvious problem. The book contained no such map.

Scholars and collectors alike began to search for it, and by the 1890s, as the 400th anniversary of Columbus' first voyage approached, the search had become a quest for the cartographical Holy Grail. "No lost maps have ever been sought for so diligently as these," Britain's Geographical Journal declared at the turn of the century, referring both to the large map and the globe. But nothing turned up. In 1896, the historian of discovery John Boyd Thacher simply threw up his hands. "The mystery of the map," he wrote, "is a mystery still."

On March 4, 1493, seeking refuge from heavy seas, a storm-battered caravel flying the Spanish flag limped into Portugal's Tagus River estuary. In command was one Christoforo Colombo, a Genoese sailor destined to become better known by his Latinized name, Christopher Columbus. After finding a suitable anchorage site, Columbus dispatched a letter to his sponsors, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain, reporting in exultation that after a 33-day crossing he had reached the Indies, a vast archipelago on the eastern outskirts of Asia.

The Spanish sovereigns greeted the news with excitement and pride, though neither they nor anybody else initially assumed that Columbus had done anything revolutionary. European sailors had been discovering new islands in the Atlantic for more than a century—the Canaries, the Madeiras, the Azores, the Cape Verde islands. People had good reason, based on the dazzling variety of islands that dotted the oceans of medieval maps, to assume that many more remained to be found.

Some people assumed that Columbus had found nothing more than a few new Canary Islands. Even if Columbus had reached the Indies, that didn't mean he had expanded Europe's geographical horizons. By sailing west to what appeared to be the Indies (but in actuality were the islands of the Caribbean), he had confirmed an ancient theory that nothing but a small ocean separated Europe from Asia. Columbus had closed a geographical circle, it seemed—making the world smaller, not larger.

But the world began to expand again in the early 1500s. The news first reached most Europeans in letters by Amerigo Vespucci, a Florentine merchant who had taken part in at least two voyages across the Atlantic, one sponsored by Spain, the other by Portugal, and had sailed along a giant continental landmass that appeared on no maps of the time. What was sensational, even mind-blowing, about this newly discovered land was that it stretched thousands of miles beyond the Equator to the south. Printers in Florence jumped at the chance to publicize the news, and in late 1502 or early 1503 they printed a doctored version of one of Vespucci's letters, under the title Mundus Novus, or New World, in which he appeared to say that he'd discovered a new continent. The work quickly became a best seller.

"In the past," it began, "I have written to you in rather ample detail about my return from those new regions...and which can be called a new world, since our ancestors had no knowledge of them, and they are entirely new matter to those who hear about them. Indeed, it surpasses the opinion of our ancient authorities, since most of them assert that there is no continent south of the equator....[But] I have discovered a continent in those southern regions that is inhabited by more numerous peoples and animals than in our Europe, or Asia or Africa."

This passage has been described as a watershed moment in European geographical thought—the moment at which a European first became aware that the New World was distinct from Asia. But "new world" didn't necessarily mean then what it means today. Europeans used it regularly to describe any part of the known world that they had not previously visited or seen described. In fact, in another letter, unambiguously attributed to Vespucci, he made clear where he thought he had been on his voyages. "We concluded," he wrote, "that this was continental land—which I esteem to be bounded by the eastern part of Asia."

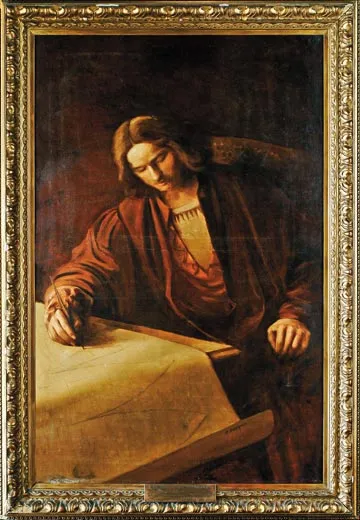

In 1504 or so, a copy of the New World letter fell into the hands of an Alsatian scholar and poet named Matthias Ringmann. Then in his early 20s, Ringmann taught school and worked as a proofreader at a small printing press in Strasbourg, but he had a side interest in classical geography—specifically, the work of Ptolemy. In a work known as the Geography, Ptolemy had explained how to map the world in degrees of latitude and longitude, a system he had used to stitch together a comprehensive picture of the world as it was known in antiquity. His maps depicted most of Europe, the northern half of Africa and the western half of Asia, but they didn't, of course, include all the parts of Asia visited by Marco Polo in the 13th century, or the parts of southern Africa discovered by the Portuguese in the latter half of the 15th century.

When Ringmann came across the New World letter, he was immersed in a careful study of Ptolemy's Geography, and he recognized that Vespucci, unlike Columbus, appeared to have sailed south right off the edge of the world that Ptolemy had mapped. Thrilled, Ringmann printed his own version of the New World letter in 1505—and to emphasize the southness of Vespucci's discovery, he changed the work's title from New World to On the Southern Shore Recently Discovered by the King of Portugal, referring to Vespucci's sponsor, King Manuel.

Not long afterward, Ringmann teamed up with a German cartographer named Martin Waldseemüller to prepare a new edition of Ptolemy's Geography. Sponsored by René II, the Duke of Lorraine, Ringmann and Waldseemüller set up shop in the little French town of St. Dié, in the mountains just southwest of Strasbourg. Working as part of a small group of humanists and printers known as the Gymnasium Vosagense, the pair developed an ambitious plan. Their edition would include not only 27 definitive maps of the ancient world, as Ptolemy had described it, but also 20 maps showing the discoveries of modern Europeans, all drawn according to the principles laid out in the Geography—a historical first.

Duke René seems to have been instrumental in inspiring this leap. From unknown contacts he had received yet another Vespucci letter, also falsified, describing his voyages and at least one nautical chart depicting the new coastlines explored to date by the Portuguese. The letter and the chart confirmed to Ringmann and Waldseemüller that Vespucci had indeed discovered a huge unknown land across the ocean to the west, in the Southern Hemisphere.

What happened next is unclear. At some time in 1505 or 1506, Ringmann and Waldseemüller decided that the land Vespucci had explored was not a part of Asia. Instead, they concluded that it must be a new, fourth part of the world.

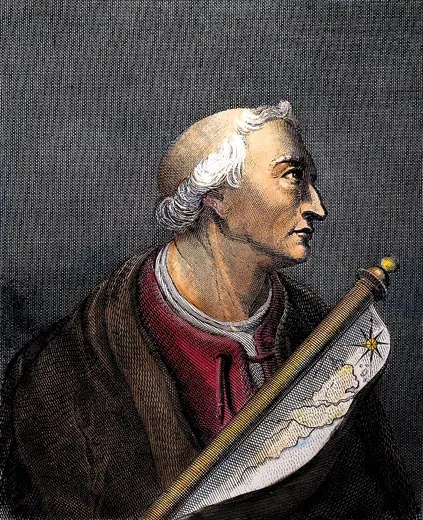

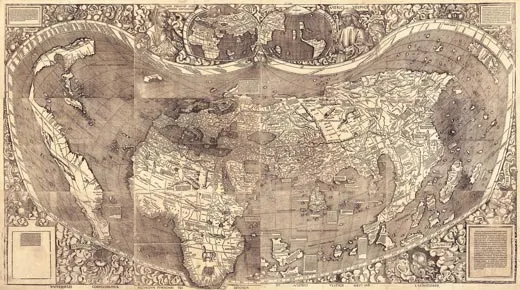

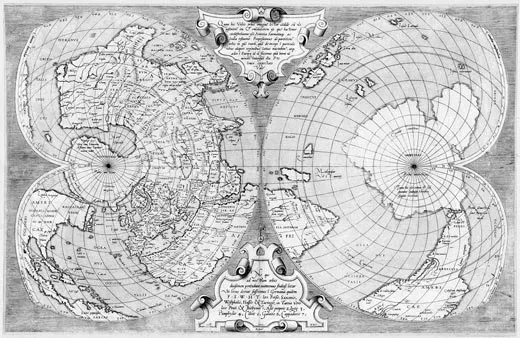

Temporarily setting aside their work on their Ptolemy atlas, Ringmann and Waldseemüller threw themselves into the production of a grand new map that would introduce Europe to this new idea of a four-part world. The map would span 12 separate sheets, printed from carefully carved wood blocks; when pasted together, the sheets would measure a stunning 4 1/2 by 8 feet—creating one of the largest printed maps, if not the largest, ever produced to that time. In April of 1507, they began printing the map, and would later report turning out 1,000 copies.

Much of what the map showed would have come as no surprise to Europeans familiar with geography. Its depiction of Europe and North Africa derived directly from Ptolemy; sub- Saharan Africa derived from recent Portuguese nautical charts; and Asia derived from the works of Ptolemy and Marco Polo. But on the left side of the map was something altogether new. Rising out of the formerly uncharted waters of the Atlantic, stretching almost from the map's top to its bottom, was a strange new landmass, long and thin and mostly blank—and there, written across what is known today as Brazil, was a strange new name: America.

Libraries today list Martin Waldseemüller as the author of the Introduction to Cosmography, but the book does not actually single him out as such. It includes opening dedications by both him and Ringmann, but these refer to the map, not the text—and Ringmann's dedication comes first. In fact, Ringmann's fingerprints are all over the work. The book's author, for instance, demonstrates a familiarity with ancient Greek—a language that Ringmann knew well but Waldseemüller did not. The author embellishes his writing with snatches of verse by Virgil, Ovid and other classical writers—a literary tic that characterizes all of Ringmann's writing. And the one contemporary writer mentioned in the book was a friend of Ringmann's.

Ringmann the writer, Waldseemüller the mapmaker: the two men would team up in precisely this way in 1511, when Waldseemüller printed a grand map of Europe. Accompanying the map was a booklet titled Description of Europe, and in dedicating his map to Duke Antoine of Lorraine, Waldseemüller made clear who had written the book. "I humbly beg of you to accept with benevolence my work," he wrote, "with an explanatory summary prepared by Ringmann." He might just as well have been referring to the Introduction to Cosmography.

Why dwell on this arcane question of authorship? Because whoever wrote the Introduction to Cosmography was almost certainly the person who coined the name "America"—and here, too, the balance tilts in Ringmann's favor. The famous naming-of-America paragraph sounds a lot like Ringmann. He's known, for example, to have spent time mulling over the use of feminine names for concepts and places. "Why are all the virtues, the intellectual qualities and the sciences always symbolized as if they belonged to the feminine sex?" he would write in a 1511 essay. "Where does this custom spring from: a usage common not only to the pagan writers but also to the scholars of the church? It originated from the belief that knowledge is destined to be fertile of good works....Even the three parts of the old world received the name of women."

Ringmann reveals his hand in other ways. In both poetry and prose he regularly amused himself by making up words, by punning in different languages and by investing his writing with hidden meanings. The naming-of-America passage is rich in just this sort of wordplay, much of which requires a familiarity with Greek. The key to the whole passage, almost always overlooked, is the curious name Amerigen (which Ringmann quickly Latinizes and then feminizes to come up with America). To get Amerigen, Ringmann combined the name Amerigo with the Greek word gen, the accusative form of a word meaning "earth," and by doing so coined a name that means—as he himself explains—"land of Amerigo."

But the word yields other meanings. Gen can also mean "born" in Greek, and the word ameros can mean "new," making it possible to read Amerigen as not only "land of Amerigo" but also "born new"—a double-entendre that would have delighted Ringmann, and one that very nicely complements the idea of fertility that he associated with female names. The name may also contain a play on meros, a Greek word sometimes translated as "place." Here Amerigen becomes A-meri-gen, or "No-place-land"—not a bad way to describe a previously unnamed continent whose geography is still uncertain.

Copies of the Waldseemüller map began to appear at German universities in the decade after 1507; sketches of it and copies made by students and professors in Cologne, Tübingen, Leipzig and Vienna survive. The map clearly was getting around, as was the Introduction to Cosmography itself. The little book was reprinted several times and attracted acclaim across Europe, largely because of the long Vespucci letter.

What about Vespucci himself? Did he ever come across the map or the Introduction to Cosmography? Did he ever learn that the New World had been named in his honor? The odds are that he did not. Neither the book nor the name is known to have made it to the Iberian Peninsula before he died, in Seville, in 1512. But both surfaced there soon afterward: the name America first appeared in Spain in a book printed in 1520, and Christopher Columbus' son Ferdinand, who lived in Spain, acquired a copy of the Introduction to Cosmography sometime before 1539. The Spanish didn't like the name, however. Believing that Vespucci had somehow named the New World after himself, usurping Columbus' rightful glory, they refused to put the name America on official maps and documents for two more centuries. But their cause was lost from the start. The name America, such a natural poetic counterpart to Asia, Africa and Europa, had filled a vacuum, and there was no going back, especially not after the young Gerardus Mercator, destined to become the century's most influential cartographer, decided that the whole of the New World, not just its southern part, should be so labeled. The two names he put on his 1538 world map are the ones we've used ever since: North America and South America.

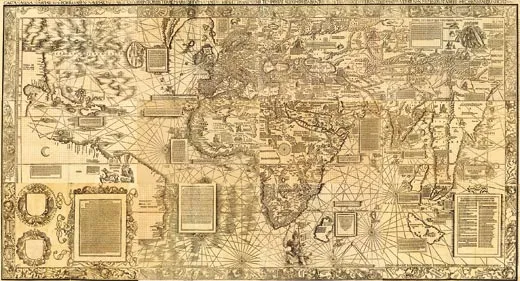

Ringmann didn't have long to live after finishing the Introduction to Cosmography. By 1509 he was suffering from chest pains and exhaustion, probably from tuberculosis, and by the fall of 1511, not yet 30, he was dead. After Ringmann's death Waldseemüller continued to make maps, including at least three that depicted the New World, but never again did he depict it as surrounded by water, or call it America—more evidence that these ideas were Ringmann's. On one of his later maps, the Carta Marina of 1516—which identifies South America only as "Terra Nova"—Waldseemüller even issued a cryptic apology that seems to refer to his great 1507 map: "We will seem to you, reader, previously to have diligently presented and shown a representation of the world that was filled with error, wonder, and confusion.... As we have lately come to understand, our previous representation pleased very few people. Therefore, since true seekers of knowledge rarely color their words in confusing rhetoric, and do not embellish facts with charm but instead with a venerable abundance of simplicity, we must say that we cover our heads with a humble hood."

Waldseemüller produced no other maps after the Carta Marina, and some four years later, on March 16, 1520, in his mid-40s, he died—"dead without a will," a clerk would later write when recording the sale of his house in St. Dié.

During the decades that followed, copies of the 1507 map wore out or were discarded in favor of more up-to-date and better-printed maps, and by 1570 the map had all but vanished. One copy did survive, however. Sometime between 1515 and 1517, the Nuremberg mathematician and geographer Johannes Schöner acquired a copy and bound it into a beechwood-covered folio that he kept in his reference library. Between 1515 and 1520, Schöner studied the map carefully, but by the time he died, in 1545, he probably had not opened it in years. The map had begun its long sleep, which would last more than 350 years.

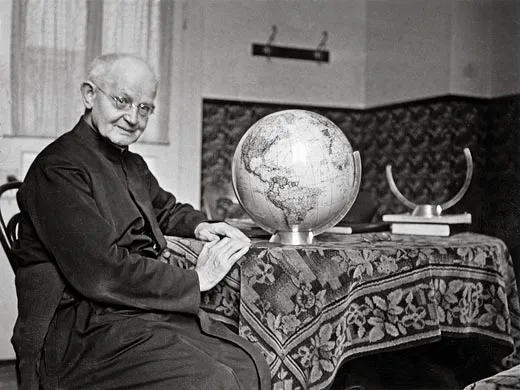

It was found again by accident, as happens so often with lost treasures. In the summer of 1901, freed from his teaching duties at Stella Matutina, a Jesuit boarding school in Feldkirch, Austria, Father Joseph Fischer set out for Germany. Balding, bespectacled and 44 years old, Fischer was a professor of history and geography. For seven years he had been haunting the public and private libraries of Europe in his spare time, hoping to find maps that showed evidence of the early Atlantic voyages of the Norsemen. This current trip was no exception. Earlier in the year, Fischer had received word that the impressive collection of maps and books at Wolfegg Castle, in southern Germany, included a rare 15th-century map that depicted Greenland in an unusual way. He had to travel only some 50 miles to reach Wolfegg, a tiny town in the rolling countryside just north of Austria and Switzerland, not far from Lake Constance. He reached the town on July 15, and upon his arrival at the castle, he would later recall, he was offered "a most friendly welcome and all the assistance that could be desired."

The map of Greenland turned out to be everything Fischer had hoped. As was his custom on research trips, after studying the map Fischer began a systematic search of the castle's entire collection. For two days he made his way through the inventory of maps and prints and spent hours immersed in the castle's rare books. And then, on July 17, his third day there, he walked over to the castle's south tower, where he had been told he would find a small second-floor garret containing what little he hadn't yet seen of the castle's collection.

The garret is a simple room. It's designed for storage, not show. Bookshelves line three of its walls from floor to ceiling, and two windows let in a cheery amount of sunlight. Wandering about the room and peering at the spines of the books on the shelves, Fischer soon came across a large folio with beechwood covers, bound together with finely tooled pigskin. Two Gothic brass clasps held the folio shut, and Fischer gently pried them open. On the inside cover he found a small bookplate, bearing the date 1515 and the name of the folio's original owner: Johannes Schöner. "Posterity," the inscription began, "Schöner gives this to you as an offering."

Fischer started leafing through the folio. To his amazement, he discovered that it contained not only a rare 1515 star chart engraved by the German artist Albrecht Dürer, but also two giant world maps. Fischer had never seen anything quite like them. In pristine condition, printed from intricately carved wood blocks, each one was made up of separate sheets that, if removed from the folio and assembled, would create maps approximately 4 1/2 by 8 feet in size.

Fischer began examining the first map in the folio. Its title, running in block letters across the bottom of the map, read, THE WHOLE WORLD ACCORDING TO THE TRADITION OF PTOLEMY AND THE VOYAGES OF AMERIGO VESPUCCI AND OTHERS. This language brought to mind the Introduction to Cosmography, a work Fischer knew well, as did the portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci that he saw at the top of the map.

Could this be...the map? Fischer began to study it sheet by sheet. Its two center sheets, which showed Europe, northern Africa, the Middle East and western Asia, came straight from Ptolemy. Farther to the east, it presented the Far East as described by Marco Polo. Southern Africa reflected the nautical charts of the Portuguese.

It was an unusual mix of styles and sources: precisely the sort of synthesis, Fischer realized, that the Introduction to Cosmography had promised. But he began to get truly excited when he turned to the map's three western sheets. There, rising out of the sea and stretching from the top to bottom, was the New World, surrounded by water.

A legend at the bottom of the page corresponded verbatim to a paragraph in the Introduction to Cosmography. North America appeared on the top sheet, a runt version of its modern self. Just to the south lay a number of Caribbean islands, among them two big ones identified as Spagnolla and Isabella. A small legend read, "These islands were discovered by Columbus, an admiral of Genoa, at the command of the King of Spain." Moreover, the vast southern landmass stretching from above the Equator to the bottom of the map was labeled DISTANT UNKNOWN LAND. Another legend read THIS WHOLE REGION WAS DISCOVERED BY THE ORDER OF THE KING OF CASTILE. But what must have brought Fischer's heart to his mouth was what he saw on the bottom sheet: AMERICA.

The 1507 map! It had to be. Alone in the little garret in the tower of Wolfegg Castle, Father Fischer realized that he had discovered the most sought-after map of all time.

Fischer took the news of his discovery straight to his mentor, the renowned Innsbruck geographer Franz Ritter von Wieser. In the fall of 1901, after intense study, the two went public. The reception was ecstatic. "Geographical students in all parts of the world have awaited with the deepest interest details of this most important discovery," the Geographical Journal declared, breaking the news in a February 1902 essay, "but no one was probably prepared for the gigantic cartographical monster which Prof. Fischer has now awakened from so many centuries of peaceful slumber." On March 2 the New York Times followed suit: "There has lately been made in Europe one of the most remarkable discoveries in the history of cartography," its report read.

Interest in the map grew. In 1907, the London-based bookseller Henry Newton Stevens Jr., a leading dealer in Americana, secured the rights to put the 1507 map up for sale during its 400th-anniversary year. Stevens offered it as a package with the other large Waldseemüller map—the Carta Marina of 1516, which had also been bound into Schöner's folio—for $300,000, or about $7 million in today's currency. But he found no takers. The 400th anniversary passed, two world wars and the cold war engulfed Europe, and the Waldseemüller map, left alone in its tower garret, went to sleep for another century.

Today, at last, the map is awake again—this time, it would appear, for good. In 2003, after years of negotiation with the owners of Wolfegg Castle and the German government, the Library of Congress acquired it for $10 million. On April 30, 2007, almost exactly 500 years after its making, German Chancellor Angela Merkel officially transferred the map to the United States. That December, the Library of Congress put it on permanent display in its grand Jefferson Building, where it is the centerpiece of an exhibit titled "Exploring the Early Americas."

As you move through it, you pass a variety of priceless cultural artifacts made in the pre-Columbian Americas, and a choice selection of original texts and maps dating from the period of first contact between the New World and the Old. Finally you arrive at an inner sanctum, and there, reunited with the Introduction to Cosmography, the Carta Marina and a few other select geographical treasures, is the Waldseemüller map. The room is quiet, the lighting dim. To study the map you have to move close and peer carefully through the glass—and when you do, it begins to tell its stories.

Adapted from The Fourth Part of the World, by Toby Lester. © 2009 Toby Lester. Published by the Free Press. Reproduced with permission.