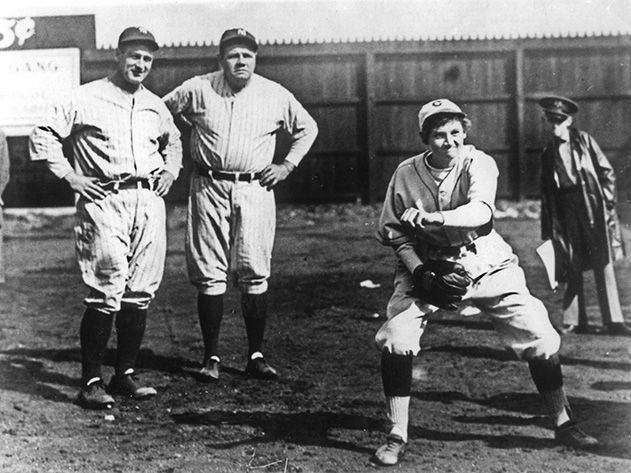

The Woman Who (Maybe) Struck out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig

Of all the strange baseball exploits of the Depression era, none was more surprising than Jackie Mitchell’s supposed feat

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Jackie-Mitchell-631.jpg)

One spring day my son came home from school and asked, “Do you know about the girl who struck out Babe Ruth?”

I smiled indulgently at this playground tall tale. But he insisted it was true. “I read a book about her in the library,” he said.

“Must have been fiction,” I churlishly replied, before consulting the Baseball Almanac to bludgeon my 10-year-old with bitter fact.

Instead, I discovered the astounding story of Jackie Mitchell, a 17-year-old southpaw who pitched against the New York Yankees on April 2, 1931. The first batter she faced was Ruth, followed by Lou Gehrig, the deadliest hitting duo in baseball history. Mitchell struck them both out. There was a box score to prove it and news stories proclaiming her “organized baseball’s first girl pitcher.”

For a lifelong baseball nerd, this was like learning that a hamster once played shortstop or that Druids invented our national pastime. The Sultan of Swat and the Iron Horse couldn’t hit a girl? Why had I never heard of her?

This led me, a month later, to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, where I learned that Jackie Mitchell’s story was even stranger than I’d supposed, with subplots involving donkeys, long beards and a lingering mystery about what transpired when she took the mound in 1931.

The Hall of Fame remains a pretty macho place, filled with plaques and exhibits honoring thousands of men who have played the game. But after touring the Babe Ruth Room and paying homage to Lou Gehrig’s locker and Stan Musial’s bat, I found a small exhibit on women in baseball, titled “Diamond Dreams.” As with so much of baseball history, determining “firsts” and separating fact from lore can be tricky. All-women teams competed against each other as early as the 1860s, and in later decades traveling squads such as the Blondes and Brunettes drew paid spectators. But most of these early players were actresses, recruited and often exploited by male owners. “It was a show, a burlesque of the game,” says Debra Shattuck, a leading expert on women in baseball.

Around the turn of the century, however, women athletes of real ability began competing with men and sometimes playing on the same teams in bygone semipro leagues. The first to appear in baseball’s minor leagues was Lizzie Arlington, who wore bloomers while pitching for the Reading (Pennsylvania) Coal Heavers against the Allentown Peanuts in 1898.

So Jackie Mitchell wasn’t the first woman to play organized baseball, but her appearance on the mound in 1931 became a Depression-era sensation. As a girl in Memphis, she’d allegedly been tutored in baseball by a neighbor and minor-league pitcher, Charles Arthur “Dazzy” Vance, who would go on to lead the National League in strikeouts for seven straight seasons. Mitchell’s family moved to Chattanooga, where she became a multisport athlete and joined a baseball school affiliated with the city’s Class AA minor-league team, the Lookouts, and attracted attention with her sinking curveball.

The Lookouts’ new president, Joe Engel, was a showman and promoter whose many stunts included trading a player for a turkey, which was cooked and served to sportswriters. In 1931, he booked the Yankees for two exhibition games against the Lookouts as the major leaguers traveled north from spring training. A week before their arrival, he announced the signing of Mitchell to what’s believed to be one of the first professional baseball contracts given to a woman.

The prospect of a 17-year-old girl facing the mighty Yankees generated considerable media coverage, most of it condescending. One paper wrote, “The curves won’t be all on the ball” when “pretty” Jackie Mitchell takes the mound. Another reported that she “has a swell change of pace and swings a mean lipstick.” The tall, slim teenager, clad in a baggy Lookouts uniform, also posed for cameras as she warmed up by taking out a mirror and powdering her nose.

The first game against the Yankees, before a crowd of 4,000 fans and journalists, began with the Lookouts’ starting pitcher surrendering hits to the first two batters. The Lookouts’ manager then pulled his starter and sent Mitchell to the mound to face the heart of a fearsome lineup that had become known in the 1920s as “Murderers’ Row.”

First up was Ruth, who tipped his hat at the girl on the mound “and assumed an easy batting stance,” a reporter wrote. Mitchell went into her motion, winding her left arm “as if she were turning a coffee grinder.” Then, with a side-armed delivery, she threw her trademark sinker (a pitch known then as “the drop”). Ruth let it pass for a ball. At Mitchell’s second offering, Ruth “swung and missed the ball by a foot.” He missed the next one, too, and asked the umpire to inspect the ball. Then, with the count 1-2, Ruth watched as Mitchell’s pitch caught the outside corner for a called strike three. Flinging his bat down in disgust, he retreated to the dugout.

Next to the plate was Gehrig, who would bat .341 in 1931 and tie Ruth for the league lead in homers. He swung at and missed three straight pitches. But Mitchell walked the next batter, Tony Lazzeri, and the Lookouts’ manager pulled her from the game, which the Yankees went on to win, 14-4.

“Girl Pitcher Fans Ruth and Gehrig,” read the headline in the next day’s sports page of the New York Times, beside a photograph of Mitchell in uniform. In an editorial, the paper added: “The prospect grows gloomier for misogynists.” Ruth, however, was quoted as saying that women “will never make good” in baseball because “they are too delicate. It would kill them to play ball every day.”

Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis evidently agreed. It was widely reported (though no proof exists) that he voided Mitchell’s contract on the grounds that baseball was too strenuous for women. The president of the organization overseeing the minor leagues later termed the appearance of “a female mound artist” a lamentable “Burlesquing” of the national pastime, akin to greased pig contests, hot dog-eating competitions and other ballpark promotions.

Mitchell’s unusual baseball career, however, wasn’t over. In an era before televised games, when blacks as well as women were unofficially barred from major-league baseball, an ersatz troupe of traveling teams barnstormed the nation, mostly playing in towns that lacked professional squads. Barnstorming mixed sports with vaudeville and circus. “There were teams of fat men, teams of one-legged men, blind teams, all-brother teams,” says Tim Wiles, director of research at the Hall of Fame library. Some teams didn’t just play standard baseball; they also performed sleight-of-hand tricks, like the Harlem Globetrotters, and rode animals onto the field.

One such team was called House of David, named for a religious colony in Michigan that sought to gather the lost tribes of Israel in advance of the millennium. The colony’s tenets included celibacy, vegetarianism and a devotion to physical fitness, which led to the creation of a talented and profitable ball team. In accordance with House of David beliefs, players had shoulder-length hair and biblical beards. The eccentric team was so popular that it spawned spinoffs, including an all-black Colored House of David.

Over time, the colony’s teams also recruited players from outside their community, and in 1933 a House of David squad signed Jackie Mitchell, who was then 19 and had been playing with various amateur teams since her outing against the Yankees. Chaperoned by her mother, she traveled with the team and in one game pitched against the major-league St. Louis Cardinals. According to a news report, the “nomadic House of David ball team, beards, girl pitcher and all, came, saw, and conquered the Cardinals, 8 to 6.”

Little else is known of Mitchell’s time with House of David, though according to some sources she became weary of the team’s “circus-type” antics: for instance, some players donning fake beards or playing ball while riding donkeys. In 1937 she retired from baseball and went to work for her father’s optical business in Tennessee.

But other women continued to play on barnstorming teams, including Negro League squads, and after 1943 in the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (featured in the movie A League of Their Own). Then in 1952, another woman followed Mitchell into baseball’s minor leagues. Eleanor Engle, a softball player and stenographer in Pennsylvania, joined the Harrisburg Senators and was pictured in uniform in the team’s dugout. But she never took the field, and the president of the minor leagues stated that no contract with a woman would be approved because it was “not in the best interest of baseball that such travesties be tolerated.” This prompted a media flurry and a tongue-in-cheek protest from Marilyn Monroe. “The lady should be permitted to play,” said the actress, who would soon marry Joe DiMaggio. “I can’t think of a better way to meet outfielders.”

Only in recent decades have women gained a degree of acceptance playing alongside men. In the 1970s, a lawsuit won girls entry into Little League. In the 1980s, women broke into men’s college ball and in the 1990s, Ila Borders joined the St. Paul Saints of the independent Northern League. But no female player has yet reached the majors, or come close to matching Mitchell’s feat of striking out two of the game’s greatest hitters. Which raises a question that has lingered since the day she took the mound in 1931. Did her pitching really fool Ruth and Gehrig, or did the two men whiff on purpose?

The Lookouts’ president, Joe Engel, clearly signed Mitchell to attract publicity and sell tickets, both of which he achieved. And some news reports on the game hinted at a less than sincere effort by Ruth and Gehrig. Of Ruth’s at bat, the New York Times wrote that he “performed his role very ably” by striking out before the delighted Chattanooga crowd, while Gehrig “took three hefty swings as his contribution to the occasion.” Also, the game was originally scheduled for April 1 and delayed a day because of rain, leading to speculation that Engel had plotted Mitchell’s outing as an April Fools’ Day prank.

If Ruth and Gehrig were in on an orchestrated stunt, they never said so. Other Yankees later gave mixed verdicts. Pitcher Lefty Gomez said the Yankees manager, Joe McCarthy, was so competitive that “he wouldn’t have instructed the Yankees to strike out.” Third baseman Ben Chapman, who was due to bat when Mitchell was pulled from the mound, said he “had no intention of striking out. I planned to hit the ball.” But he suspected Ruth and Gehrig agreed between themselves to strike out. “It was a good promotion, a good show,” he said. “It really packed the house.”

Mitchell, for her part, held to her belief that she’d genuinely whiffed the two Yankees. She said the only instruction the Yankees received was to try to avoid lining the ball straight back at the mound, for fear of hurting her. “Why, hell, they were trying, damn right,” she said of Ruth and Gehrig not long before her death in 1987. “Hell, better hitters than them couldn’t hit me. Why should they’ve been any different?”

She also saved a newsreel of her outing, which shows her hitting the strike zone on three consecutive pitches to Ruth. On two of them, Ruth flails wildly at the ball, and his fury at the called third strike looks theatrical. But the images are too blurry to tell how much speed and sink Mitchell had on her pitches, and whether they were good enough to miss the bats of both Ruth and Gehrig.

Debra Shattuck, the historian of women in baseball, is skeptical. While Mitchell may have been a good pitcher, she says, “I really doubt she could hold her own at that level.” But Tim Wiles, the Hall of Fame research director, thinks it’s possible the strikeouts were genuine. “Much of batting has to do with timing and familiarity with a pitcher, and everything about Jackie Mitchell was unfamiliar to Ruth and Gehrig,” he says. Also, Mitchell was a lefty side-armer facing lefty batters, a matchup that favors the pitcher. And Ruth striking out wasn’t a rarity; he did so 1,330 times in his career, leading the league in that category five times.

Wiles also wonders if sportswriters and players who suggested that the strikeouts were staged did so to protect male egos. “Even hitters as great as Ruth and Gehrig would be reluctant to admit they’d really been struck out by a 17-year-old girl,” he says.

John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball, vigorously disagrees. He believes Ruth and Gehrig were in cahoots with the Lookouts’ president and went along with the stunt, which did no harm to their reputations. “The whole thing was a jape, a jest, a Barnumesque prank,” he says. “Jackie Mitchell striking out Ruth and Gehrig is a good story for children’s books, but it belongs in the pantheon with the Easter Bunny and Abner Doubleday ‘inventing’ baseball.”

He adds, however, that a great deal has changed since Mitchell’s day and that there are fewer obstacles to women succeeding and being accepted in professional baseball today. No rule prohibits them doing so, and in 2010, Eri Yoshida, a knuckleballer who has played professional ball in Japan, trained with the Red Sox at their minor-league camp. A year later, Justine Siegal became the first woman to throw batting practice for a major-league team.

In Thorn’s view, it is players like Yoshida, throwing knucklers or other off-speed pitches, who represent the likeliest path to the majors for women. Asked if this breakthrough might occur in his lifetime, the 66-year-old historian pauses before replying: “If I live to 100, yes. I believe it could be possible.”

My son, for one, thinks it will happen much sooner than that. Shortly before our visit to Cooperstown, his Little League team was defeated in a playoff game by a team whose girl pitcher struck out batter after batter and stroked several hits, too. No one on the field or sidelines seemed to consider her gender noteworthy.

“Don’t be sexist, Dad,” my son chided when I asked if he was surprised by the girl’s play. “I wish she was on our team.”