Before There Was “Hamilton,” There Was “Burr”

Although Gore Vidal’s book never became a hit on Broadway, the novel helped create the public personae of Alexander Hamilton’s nemesis

:focal(602x214:603x215)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/18/3d/183d8696-559b-4352-a8bd-197fe7bfa9c7/hamiltonbway0228r-leslie-odom-jr-as-aaron-burr-wr.jpg)

“Who lives? Who dies? Who tells your story?” sing the cast of Hamilton in the finale of the smash Broadway musical. In the case of Aaron Burr—the “damn fool” who shot Alexander Hamilton—the answer to that last question, at least before playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda came around, was simple: Gore Vidal.

More than 40 years before there was Hamilton, there was Burr, the best-selling and critically acclaimed 1973 novel about the disgraced Founding Father—written by a celebrity author with a reputation as a skilled duelist himself (albeit with words, not pistols).

Vidal died in 2012. In his obituary, the New York Times called Vidal a “prolific, elegant, all-around man of letters.” He was also a successful television writer in the medium’s early days, and a regular on the talk show circuit later in his career (Reportedly, Johnny Carson was impressed enough to offer him a spot as a regular guest host of “The Tonight Show”). The aristocratic Vidal also dabbled in politics: He ran for Congress from New York in 1960, and for the Senate in California in 1982. “Though he lost both times,” noted the Times’ Charles McGrath, “he often conducted himself as a sort of unelected shadow president. He once said, ‘There is not one human problem that could not be solved if people would simply do as I advise.’”

His sharp wit and on-camera poise was best displayed in his debates with luminaries like conservative ideologue William F. Buckley, founder of the National Review. (2015’s documentary Best of Enemies highlights these vituperative but entertaining televised fights between two heavyweight intellectuals of the left and right.)

Vidal began writing about Burr in late 1969. That was the year after the debates which, along with the publication of his scandalous sex satire, Myra Breckenridge, had helped propel the then 43-year-old to national prominence.

“At the time he begins writing Burr, he’s on the top of his game,” says Jay Parini author of the 2015 Vidal biography, Empire of Self. “He’s been on the cover of Time, Life and Look. He’s everywhere.”

So what got a man so very much in-the-moment interested in a character 200 years in the past? Parini cites multiple reasons, from the nation’s excitement over the anticipated bicentennial celebration of its independence in 1976 to his stepfather’s purported distant relationship with Burr to the shadowy machinations of the Nixon White House reminding Vidal of the intrigues of the Jefferson White House. In addition to those motivations, Vidal wanted to continue his exploration the historical novel—a genre he had experimented with in his 1964 novel Julian about the Roman emperor Flavius Claudius Julianus.

But perhaps most significantly, says Parini, a writer and professor at Middlebury College in Vermont, who was also Vidal’s friend for nearly 30 years ,“I think he saw himself in Burr.”

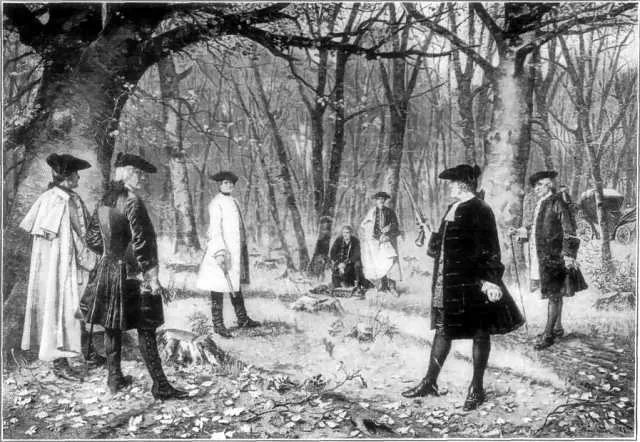

Certainly few characters in early American history have sparked such passion as the man who fought with distinction in the American Revolution and lived well into the Industrial Revolution. In between, of course, he figured prominently into two of the most infamous episodes in the history of the early Republic: The 1804 duel in which Burr—then vice president of the United States—shot and killed Hamilton; and the so-called “Burr Conspiracy” three years later, when he was ordered arrested by President Thomas Jefferson and charged with treason, allegedly for plotting to create an independent nation in the Southwest, taking some of the United States with him (Burr’s defenders maintained he wanted to “liberate” Mexico from Spain). The truth was somewhere in the middle. Historian Nancy Isenberg writes in her 2007 biography of Burr, Fallen Founder, that “Burr never planned the grand conspiracy that attached to him, and neither did he seriously contemplate the assassination of the president or his own installation as emperor of Mexico” (all things he was charged with at various points). “But it seems undeniable that he was foolish in his dealings with Jefferson.”. After a trial that gripped the new nation, presided over by Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, Burr was acquitted of treason, and his political career was over.

Vidal certainly wasn’t the first writer to recognize that Burr’s life made for a fascinating story. In her book, Isenberg traces the history of Burr-Lit, noting that as early as 1838—two years after his death—the “devilish Burr” made an appearance in a novel about his alleged schemes in the West.

While he would have his defenders in print over the subsequent years, most depictions of Burr were ugly. Isenberg notes that even as late as 1955, playwright Thomas Sweeney, in his “Aaron Burr’s Dream for the Southwest,” depicts the former vice president as “a hypersexualized and insane genius...a weird blend of Dr. Frankenstein and Hugh Hefner.”

It’s likely that Vidal would have been familiar with most of these earlier works when he began researching his own novel on Burr. He was known for exhaustive research – when he wrote Julian he moved to Rome to spend a year immersed in the history of the Roman Empire. Parini describes his research zeal as “fanatical...he would buy up books on the subject and talk to experts at length.” Burr was no exception: To prepare for his novel, he consulted with his friend and historian Arthur Schlesinger on the most useful books and sources, and had about 200 volumes shipped to his residence in Rome.

Every morning, Vidal would head to a café near the Pantheon and sip coffee as he began to immerse himself in the period, and the character. “I was beginning to feel the weight of the book, and worked easily,” Vidal later told Parini. At first, “I had in mind only the glimmer of a sequence.”

While there was certainly plenty for him to read, part of the problem in re-telling Burr’s story, fictional or historically, is the paucity of his personal papers. “People don’t realize that the archive shapes the story,” says Isenberg, a professor of history at Louisiana State University. As opposed to the other Founding Fathers, who left extensive troves of documents—not to mention, as in the case of Hamilton, children and a widow to manage them and help shape the legacy—most of Burr’s papers went down at sea, along with his only child, daughter Theodosia, and grandson, in 1813.

Without many of his own words left for historians to use in his own defense, Burr has been at a disadvantage in posterity, which tends to paint him as an elusive and dark figure,

“He’s always stood in for this role to be the villain, the traitor,” Isenberg says.

Not that there weren’t supporters. One of them was John Greenwood, who knew Burr later in life. Greenwood was a clerk and student in Burr’s law office from 1814-1820. Years later, and by then a judge, Greenwood gave an address to the Long Island Historical Society on his old mentor. He recalled Burr, who would have been in his 60s at the time Greenwood clerked for him, as a good storyteller with seemingly few unpleasant memories, and asa man who would go to great lengths to help a friend. “His manners were cordial and his carriage graceful, and he had a winning smile,” said Judge Greenwood who also noted that Burr’s “self-possession under the most trying circumstances was wonderful...he probably never knew what it was to fear a human being.”

Greenwood’s remarks were later reprinted by the late 19th-century biographer James Parton. Published in 1892, The Life and Times of Aaron Burr was likely one of the books consumed by Vidal in his preparations for his novel, as his Burr sounds very much like the one described by the Judge.

Researching and writing Burr took Vidal several years. In between working on Burr, he wrote a Broadway play An Evening with Richard Nixon that lasted 13 performances, and also contributed articles and reviews (he was a frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books and Esquire). But the main focus of his effort for the two years leading up to its publication was Burr. In his 1999 book, Gore Vidal: A Biography, historian Fred Kaplan cites a letter from Vidal to his editor in June, 1972, expressing satisfaction with his progress on the novel. “70,000 words written, about a third I would think,” he wrote. “Odd things are happening to my characters, but then again, look what happened to their Republic?”

The finished novel was a story within a story: The narrator is one of the few fictional characters in the book, Charles Schuyler, a young journalist who is hired to write Burr’s memoir. (A few pages into the novel, Burr has Schuyler make the point that “I was not one of the Schuylers,” a reference to Alexander Hamilton’s storied in-laws. It’s unclear why Vidal gave his narrator this surname...although maybe it was an inside joke). The memoir is designed to discredit presidential hopeful Martin Van Buren-—in the hopes that “The Colonel” (as Burr is referred to throughout the book) will somehow reveal that Van Buren is really his illegitimate son, an actual rumor that existed at the time. Although far apart in age, Burr and Van Buren were good friends who agreed on many issues, says Isenberg. “The resemblance between the two men extended to their personal appearance,” she wrote in Fallen Founder. “Each was of small build, dressed meticulously, and was called a ‘dandy.’ Rumors later circulated that Van Buren was Burr’s bastard child. He was not.”

Schuyler has mixed feelings about his mission, as he grows fond of Burr—whose reminisces for the memoir are the second narrative of the book. These offer the opportunity for much Founder-bashing by Vidal. In particular, George Washington (“He had the hips, buttocks and bosom of a woman”) and Jefferson (“The most charming man I ever knew, and the most deceitful”), are skewered by his Burr. The former is further depicted as a vainglorious, inept general—while Vidal’s Burr tweaks Jefferson for his cowardice during the Revolution, fleeing ignominiously at the approach of the British and leaving Virginia without a governor. Burr, through Vidal’s deliciously acerbic writing, asserts that Jefferson’s much-vaunted inventions frequently broke and that he was a bad fiddle player.

Critics loved it. Burr was published by Random House in late 1973 to lavish praise. “What a clever piece of machinery is Mr. Vidal's complicated plot!” wrote New York Times critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt. “By setting the present- tense of his story in the 1830s and having Aaron Burr recall in his lively old age his memories of the Revolutionary War, the early history of the Republic, and his famous contests with Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson (as if these mythic events had happened only yesterday)--what a telescoping of the legendary past Mr. Vidal achieves, and what leverage it gives him to tear that past to tatters.”

Burr soared up the best-seller list and remains in print today. “Gore never got prizes,” Parini said. “He was, “not part of the literary establishment in that way.” But his work did have an impact on politics, albeit an unexpected and much-delayed one. In a 2010 speech to fellow Republicans in Troy, Michigan, Rep. Michelle Bachmann claimed Burr as the reason she became a Republican. She was a student in college at the time, and a Democrat. "Until I was reading this snotty novel called Burr, by Gore Vidal, and read how he mocked our Founding Fathers," said Bachmann. She was so outraged by this, she told the crowd, she had to put the book down. “I was riding a train. I looked out the window and I said, 'You know what? I think I must be a Republican. I don't think I'm a Democrat.'"

Of Vidal’s 25 novels, and works of non fiction, Burr is often considered at or near the top. Writing in Slate in 2012, critic Liam Hoare, judged Burr and Vidal’s 1984 best seller Lincoln, “unsurpassed in the field of American historical fiction.”

Burr was part of what Vidal would later call his “Narratives of Empire,” a seven-volume series fictionalizing various periods of U.S history. In addition to Burr, its follow-up 1876 (in which an older Charles Schuyler re-appears) and Lincoln, the series would go on to include Empire (1987), Hollywood (1990) and The Golden Age (2000).

“I re-read (Burr) again and again, to remind myself of what the historical novel can do,” says Parini. “How it can play into the present and how it can animate the past. And how you can get into the head of a character.”

“As fiction it’s an excellent work,” agrees Isenberg. In terms of the historical veracity, “what I like is that he gives a fuller portrayal of (the Founding Fathers) as men. It’s more realistic in that it shows, yes, they had sex, yes, they engaged in land speculation.” (And yes, they frittered away their money. “The one thing that Jefferson, Hamilton and I had in common,” says Vidal’s Burr, “was indebtedness. We all lived beyond our means and on the highest scale.”)

Vidal’s urbane but cynical Burr was a perfect anti-hero for the ’70s. But what would he make of the popularity of Broadway’s ubiquitous hit? According to Parini, the usually astute Vidal missed the boat on that one. He relates a visit to Vidal by his friend Leonard Bernstein, who at the time was having trouble with his historical musical 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, which focused on the early occupants of the White House and race relations. Bernstein knew Vidal was steeped in the history of this period, and asked him to help. The writer declined, which may have been just as well considering that the show only lasted for seven performances. “I remember Gore saying to me, ‘Poor Lenny,’” Parini recalls. "'They’ll never make a Broadway musical about the Founding Fathers. I just can’t see Jefferson and Hamilton dancing across the stage.’”