TV Will Tear Us Apart: The Future of Political Polarization in American Media

In 1969, Internet pioneer Paul Baran predicted that specialized new media would undermine national cohesion

![]()

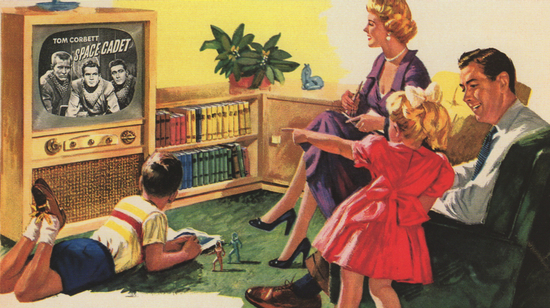

Portion of a magazine ad for Friedman-Shelby shoes showing an American family watching TV (1954)

Imagine a world where the only media you consume serves to reinforce your particular set of steadfast political beliefs. Sounds like a pretty far-out dystopia, right? Well, in 1969, Internet pioneer Paul Baran predicted just that.

In a paper titled “On the Impact of the New Communications Media Upon Social Values,” Baran (who passed away in 2011) looked at how Americans might be affected by the media landscape of tomorrow. The paper examined everything from the role of media technology in the classroom to the social effects of the portable telephone — a device not yet in existence that he predicted as having the potential to disrupt our lives immensely with unwanted calls at inopportune times.

Perhaps most interestingly, Baran also anticipated the political polarization of American media; the kind of polarization that media scholars here in the 21st century are desperately trying to better understand.

Baran understood that with an increasing number of channels on which to deliver information, there would be more and more preaching to the choir, as it were. Which is to say, that when people of the future find a newspaper or TV network or blog (which obviously wasn’t a thing yet) that perfectly fits their ideology and continuously tells them that their beliefs are correct, Americans will see little reason to communicate meaningfully with others who don’t share those beliefs.

Baran saw the media’s role as a unifying force that contributed to national cohesion; a shared identity and sense of purpose. With more specialized channels at their disposal (political or otherwise) then Americans would have very little overlap in the messages they received. This, Baran believed, would lead to political instability and increased “confrontation” on the occasions when disparate voices would actually communicate with each other.

Baran wrote in 1969:

A New Difficulty in Achieving National Cohesion. A stable national government requires a measure of cohesion of the ruled. Such cohesion can be derived from an implicit mutual agreement on goals and direction — or even on the processes of determining goals and direction. With the diversity of information channels available, there is a growing ease of creating groups having access to distinctly differing models of reality, without overlap. For example, nearly every ideological group, from the student underground to the John Birchers, now has its own newspapers. Imagine a world in which there is a sufficient number of TV channels to keep each group, and in particular the less literate and tolerant members of the groups, wholly occupied? Will members of such groups ever again be able to talk meaningfully to one another? Will they ever obtain at least some information through the same filters so that their images of reality will overlap to some degree? Are we in danger of creating by electrical communications such diversity within society as to remove the commonness of experience necessary for human communication, political stability, and, indeed, nationhood itself? Must “confrontation” increasingly be used for human communication?

National political diversity requires good will and intelligence to work comfortably. The new visual media are not an unmixed blessing. This new diversity causes one to hope that the good will and intelligence of the nation is sufficiently broad-based to allow it to withstand the increasing communication pressures of the future.

The splintering of mass media in the United States over the past half a century has undoubtedly led to the stark “differing models of reality” that Baran describes. The true believers of any ideology will tow the party line and draw strength from their particular team’s media outlets. But the evidence remains inconclusive when it comes to the average American. Simply put, there’s not a lot of evidence that people who aren’t already highly engaged politically will be influenced by partisan media sources to become more radical or reactionary as the case may be.

Writing in the Annual Review of Political Science this year, Markus Prior explains, “Ideologically one-sided news exposure may be largely confined to small, but highly involved and influential segment of the population.” However, “there is not firm evidence that partisan media are making ordinary Americans more partisan.”

Stepping back and looking at ourselves from the perspective of a future historian, it’s easy to argue that we could still be in the early days of highly-polarized mass media. The loosening and eventual elimination of the FCC’s fairness doctrine in the 1980s saw the rise of talk radio hosts unhindered by the need to give opposing viewpoints equal airtime. The rise of the web in the mid-1990s then delivered even more channels for political voices to deliver their messages through the young Internet. User-generated online video saw its rise with the birth of YouTube in the mid-2000s allowing for the dissemination of visual media without many of the regulations politicians and content creators must normally adhere to when broadcasting over the public airwaves. The rise of social media in this decade has seen everyone from your grandmother to hate groups being given a platform to air their grievances. And tomorrow, who knows?

Just how much more polarized our nation’s mainstream political voices can become remains to be seen. But it may be safe to say that when it comes to a lack of message overlap and increased political diversity in new forms of media, Paul Baran’s 1969 predictions have long since become a reality.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matt-novak-240.jpg)