Ulysses S. Grant Launched an Illegal War Against the Plains Indians, Then Lied About It

The president promised peace with Indians — and covertly hatched the plot that provoked one of the bloodiest conflicts in the West

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/44/cf4483d4-62ff-4442-b8df-929c9afc0887/nov2016_f03_grantlakota-wr-v2.jpg)

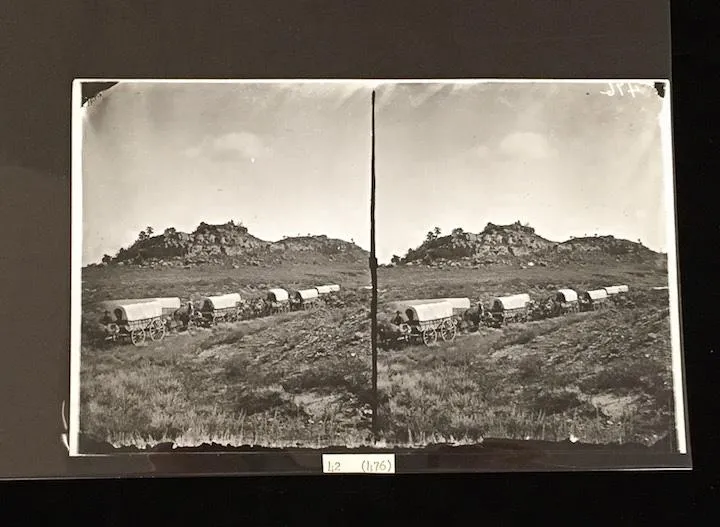

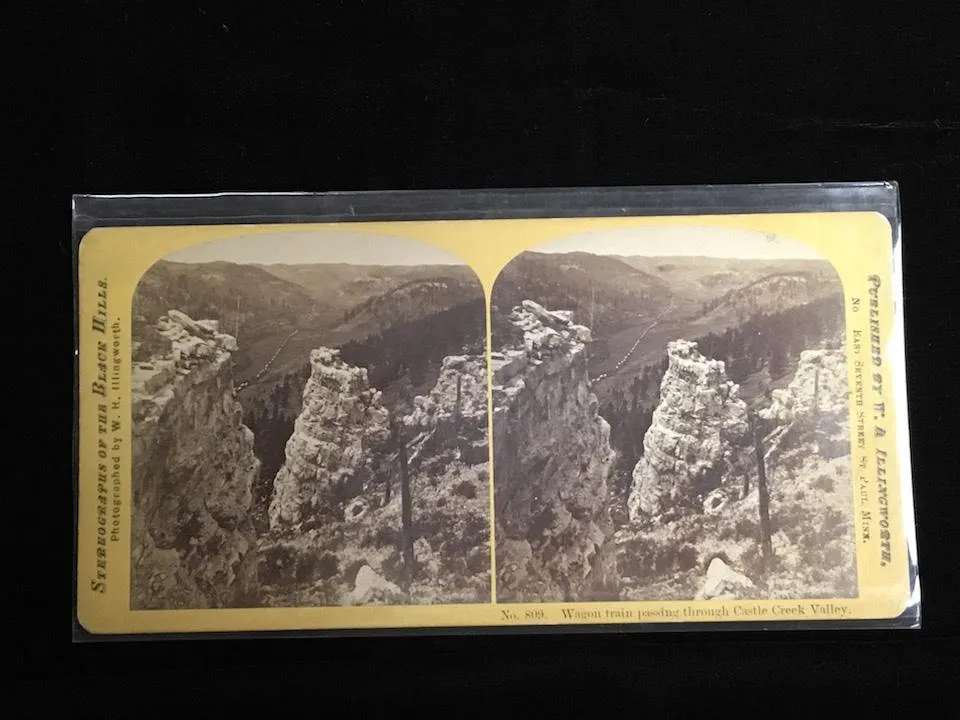

In July 1874, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a thousand-man expedition into the Black Hills, in present-day South Dakota. He was under orders to scout a suitable site for a military post, a mission personally approved by President Ulysses S. Grant, but he also brought along two prospectors, outfitted at his expense. Although largely unexplored by whites, the Black Hills were long rumored to be rich in gold, and Custer’s prospectors discovered what he reported as “paying quantities” of the precious metal. A correspondent for the Chicago Inter Ocean who accompanied the expedition was less restrained in his dispatch: “From the grass roots down it was ‘pay dirt.’” Taking him at his word, the nation’s press whipped up a frenzy over a “new El Dorado” in the American West.

The United States was going into the second year of a crippling economic depression, and the nation desperately needed a financial lift. Within a year of Custer’s discovery, more than a thousand miners had streamed into the Black Hills. Soon Western newspapers and Western congressmen were demanding that Grant annex the land.

There was one problem: The Black Hills belonged to the Lakota Indians, the most potent Indian power on the Great Plains. They had taken the territory from the Kiowas and the Crows, and they had signed a treaty with the United States guaranteeing their rights to the region. The Lakotas most esteemed the Paha Sapa (literally, “hills that are black”) not for their mystic aura, as is commonly assumed, but for their material bounty. The hills were their meat locker, a game reserve to be tapped in times of hunger.

The outcry for annexation brought Grant to a crossroads. He had taken office in 1869 on a pledge to keep the West free of war. “Our dealings with the Indians properly lay us open to charges of cruelty and swindling,” he had said, and he had staked his administration to a Peace Policy intended to assimilate Plains nations into white civilization. Now, Grant was forced to choose between the electorate and the Indians.

He had no legal reason for seizing the Black Hills, so he invented one, convening a secret White House cabal to plan a war against the Lakotas. Four documents, held at the Library of Congress and the United States Military Academy Library, leave no doubt: The Grant administration launched an illegal war and then lied to Congress and the American people about it. The episode hasn’t been examined outside the specialty literature on the Plains wars.

During four decades of intermittent warfare on the Plains, this was the only instance in which the government deliberately provoked a conflict of this magnitude, and it ultimately led to the Army’s shocking defeat at the Little Bighorn in 1876—and to litigation that remains unsettled to this day. Few observers suspected the plot at the time, and it was soon forgotten.

For most of the 20th century, historians dismissed the Grant administration as a haven for corrupt hacks, even as the integrity of the man himself remained unquestioned. More recent Grant biographers have worked hard to rehabilitate his presidency, and they have generally extolled his treatment of Indians. But they have either misinterpreted the beginnings of the Lakota war or ignored them altogether, making it appear that Grant was blameless in the greatest single Indian war waged in the West.

Throughout his military career, Grant was known as an aggressive commander, but not a warmonger. In his Personal Memoirs, he damned the Mexican War, in which he had fought, as “one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation,” and he excoriated the Polk administration’s machinations leading to hostilities: “We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it.” And yet in dealing with the Lakotas, he acted just as treacherously.

**********

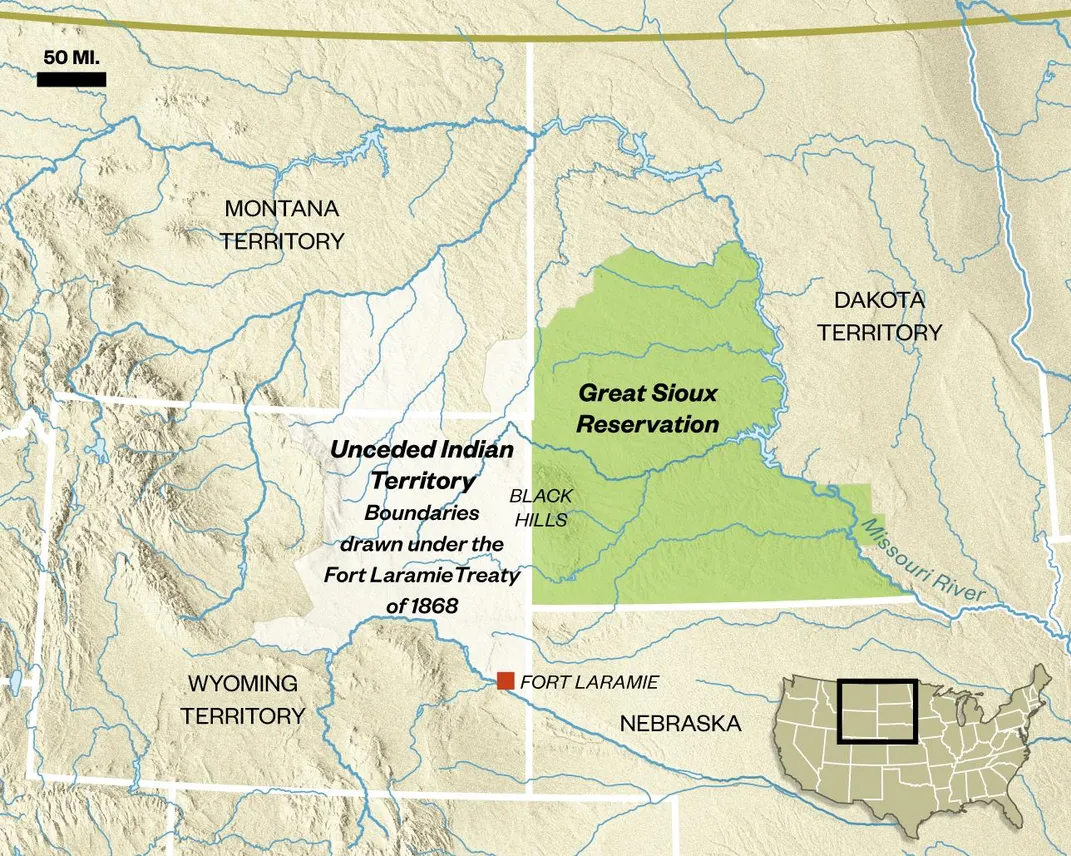

The treaty between the Lakotas and the United States had been signed at Fort Laramie in 1868, the year before Grant took office. “From this day forward,” the document began, “all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease.”

Under the Fort Laramie Treaty, the United States designated all of present-day South Dakota west of the Missouri River, including the Black Hills, as the Great Sioux Reservation, for the Lakotas’ “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation.” The treaty also reserved much of present-day northeastern Wyoming and southeastern Montana as Unceded Indian Territory, off-limits to whites without the Lakotas’ consent. To entice Lakotas onto the reservation and into farming, the United States promised to give them a pound of meat and a pound of flour a day for four years. Whether those who wished to live off the hunt rather than on the dole could actually reside in the Unceded Territory, the treaty did not say. All Lakota land, however, was to be inviolate.

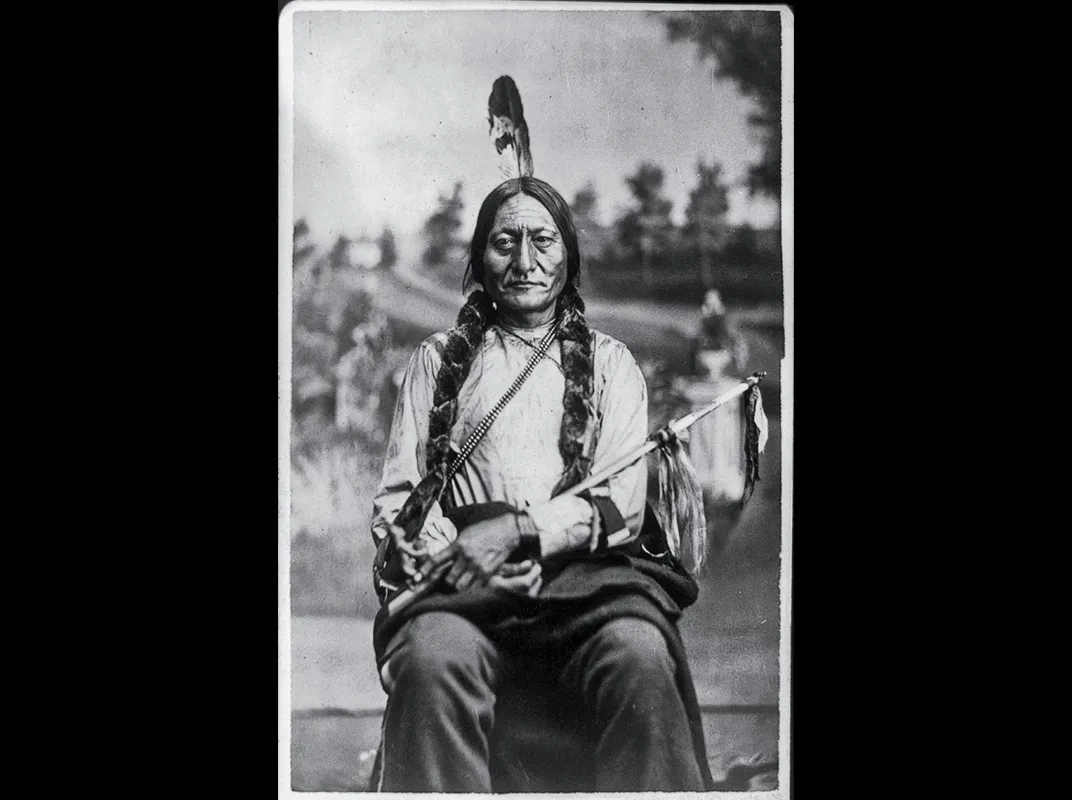

Most Lakotas settled on the reservation, but a few thousand traditionalists rejected the treaty and made their home in the Unceded Territory. Their guiding spirits were the revered war chief and holy man Sitting Bull and the celebrated war leader Crazy Horse. These “non-treaty” Lakotas had no quarrel with the wasichus (whites) so long as they stayed out of the Lakota country. This the wasichus largely did, until 1874.

Custer’s official mission that summer, finding a site for a new Army post, was permitted under the treaty. Searching for gold was not.

As the pressure rose on Grant to annex the Black Hills, his first resort was rough diplomacy. In May 1875, a delegation of Lakota chiefs came to the White House to protest shortages of government rations and the predations of a corrupt Indian agent. Grant seized the opportunity. First, he said, the government’s treaty obligation to issue rations had run out and could be revoked; rations continued only because of Washington’s kind feelings toward the Lakotas. Second, he, the Great Father, was powerless to prevent miners from overrunning the Black Hills (which was true enough, given limited Army resources). The Lakotas must either cede the Paha Sapa or lose their rations.

When the chiefs left the White House they were “all at sea,” their interpreter recalled. For three weeks, they had alternated between discordant encounters with hectoring bureaucrats and bleak hotel-room caucuses among themselves. At last, they broke off the talks and, the New York Herald reported, returned to the reservation “disgusted and not conciliated.”

Meanwhile, miners poured into the Black Hills. The task of running them out fell to Brig. Gen. George Crook, the new commander of the Military Department of the Platte, whose sympathies clearly rested with the miners. Crook evicted many of them that July, in accordance with standing policy, but before they pulled up stakes he suggested they record their claims in order to secure them for when the country opened up.

Throughout these proceedings, Crook thought the Lakotas had been remarkably forbearing. “How do the bands that sometimes roam off from the agencies on the Plains behave now?” a reporter asked him in early August.

“Well,” Crook said, “they are quiet.”

“Do you perceive any immediate danger of an Indian war?” the reporter persisted.

“Not just now,” Crook answered.

Grant gave negotiation one more try. He appointed a commission to hold a grand council on the Great Sioux Reservation and buy mining rights to the Black Hills.

The only member of the commission who knew the Lakotas was Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Terry, the urbane and kindly commander of the Department of Dakota. Why not, he suggested, encourage the Lakotas to raise crops and livestock in the Black Hills? No one listened.

The grand council convened that September but quickly foundered. Crazy Horse refused to come. So did Sitting Bull; when the commission sent a messenger to talk to him, he picked up a pinch of dirt and said, “I do not want to sell or lease any land to the government—not even as much as this.” Subchiefs and warriors from the non-treaty Lakota villages did attend the council, but to intimidate any reservation chief who might yield. Gate-crashing whites—some well-meaning and others of questionable intent—advised the reservation chiefs that the Black Hills were worth tens of millions of dollars more than the commission was prepared to offer. Those chiefs then said they would sell—if the government paid enough to sustain their people for seven generations to come.

The commission sent word back to Washington that its “ample and liberal” offer had been met with “derisive laughter from the Indians as inadequate.” The Lakotas could not be brought to terms “except by the mild exercise, at least, of force in the beginning.”

By October 1875, Grant was plotting a new course to break the impasse. Early that month, the War Department ordered Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, the ranking officer in the West, to come to Washington. The order bypassed the Army’s commanding general and Sheridan’s immediate superior, William T. Sherman. The order itself doesn’t survive, but Sheridan’s response, addressed to the adjutant general in Washington and included in Sherman’s papers at the Library of Congress, notes that he had been summoned to “see the secretary [of war] and the president on the subject of the Black Hills.” This telegram is the first of the four documents that lay out the conspiracy.

On October 8, Sheridan cut short his honeymoon in San Francisco to make his way east.

**********

Sensing trouble on the Plains, a group of New York pastors met with Grant on November 1 and exhorted him not to abandon his Peace Policy in order to satisfy a specie-starved public. That “would be a blow to the cause of Christianity throughout the world.”

“With great promptness and precision,” the New York Herald reported, the president assured the clergymen that he would never abandon the Peace Policy and “that it was his hope that during his administration it would become so firmly established as to be the necessary policy of his successors.” Smelling a rat, the Herald correspondent added, “In that he might possibly be mistaken.”

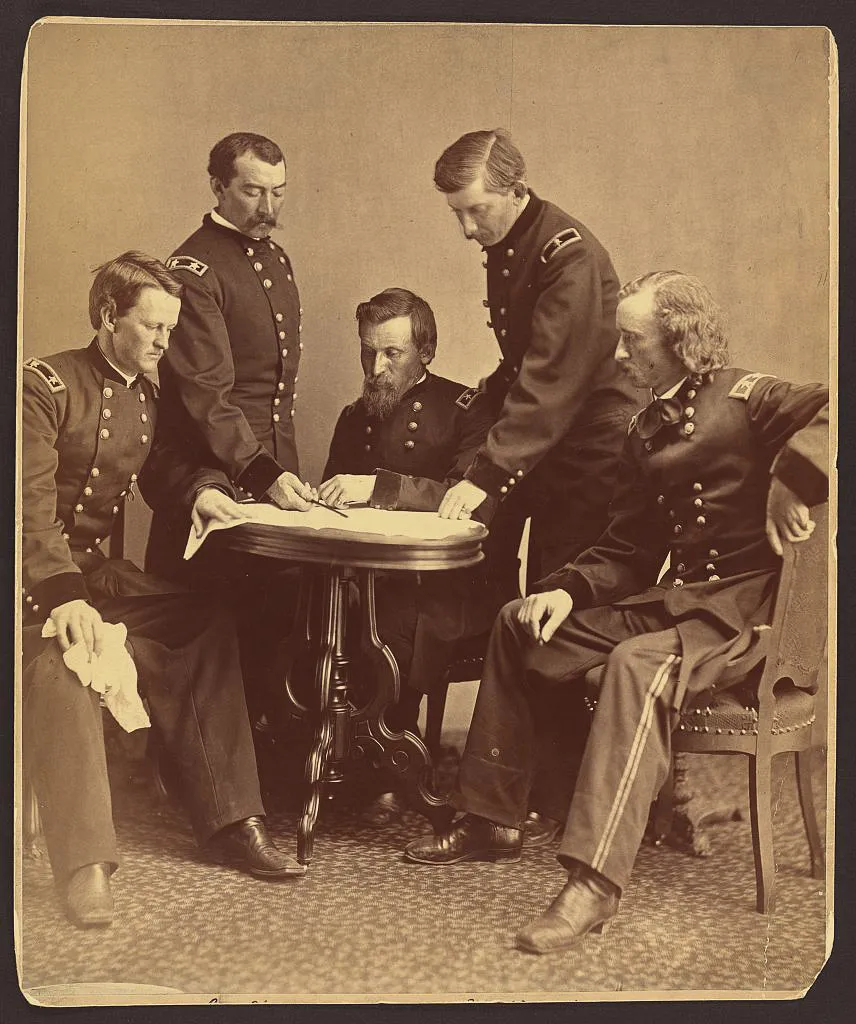

Grant was, in fact, dissembling. Just two days later, on November 3, he convened a few like-minded generals and civilian officials to formulate a war plan and write the necessary public script. On that day, the Peace Policy breathed its last.

Grant had taken nearly a month in choosing his collaborators. He knew he could count on his secretary of war, William Belknap. And earlier that fall, when he had to replace his secretary of the interior after a corruption scandal, Grant broke with the custom of consulting the cabinet on secretarial choices and privately offered the job to Zachariah Chandler, a former senator from Michigan and a hard-liner in Western affairs. Also invited were a pliable assistant interior secretary named Benjamin R. Cowen and the commissioner of Indian affairs, Edward P. Smith (who, like Belknap, would eventually leave office after a corruption scandal of his own).

Opposition to Grant’s plan might have come from his highest-ranking military officer, Sherman. He was one of the men who had signed the Fort Laramie Treaty on behalf of the United States. He advocated using force against Indians when warranted, but he had once written Grant of his anger at “whites looking for gold [who] kill Indians just as they would kill bears and pay no regard for treaties.” And though Grant and Sherman had become close friends when they led the Union to victory, they had grown apart over politics since the Civil War. After Belknap usurped the general’s command prerogatives with no objection from Grant, Sherman had moved his headquarters from Washington to St. Louis in a fit of pique. He was not invited into the cabal, though two of his subordinates—Sheridan and Crook—were.

That Grant held a meeting on November 3 was public knowledge, but the outcome was not. “It is understood the Indian question was a prominent subject of attention,” the Washington National Republican reported, “though so far as learned there was no definite decision made upon any subject relative to the policy of the Administration in its management of the Indian tribes.”

Crook, however, shared the secret with his trusted aide-de-camp Capt. John G. Bourke, and it is thanks to Bourke’s Herculean note-taking, embodied in a 124-volume diary held at the West Point library, that we can discover the secret today. Buried in one of those volumes is this entry, the second of the four incriminating documents: “General Crook said that at the council General Grant had decided that the Northern Sioux [i.e, the Lakotas] should go upon their reservation or be whipped.”

The conspirators believed that Sitting Bull and the non-treaty Lakotas had intimidated the reservation chiefs out of selling the mining rights to the Black Hills. Crush the non-treaty bands, they reasoned, and the reservation chiefs would yield.

Despite overwhelming popular support for seizing the Black Hills, Grant could expect heated opposition from Eastern politicians and the press to an unprovoked war. He needed something to shift the fault to the Lakotas.

He and his collaborators came up with a two-phase plan. First the Army would deliver the ultimatum to which Bourke referred: Repair to the reservation or be whipped. The Army would no longer enforce the edict affirming Lakota ownership of the Black Hills. This is revealed in the third document, also at the Library of Congress, a confidential order Sheridan wrote to Terry on November 9, 1875:

At a meeting which occurred in Washington on the 3d of November ...the President decided that while the orders heretofore issued forbidding the occupation of the Black Hills country by miners should not be rescinded, still no fixed resistance by the military should be made to the miners going in....

Will you therefore cause the troops in your Department to assume such attitude as will meet the views of the President in this respect.

If the Lakotas retaliated against incoming miners, so much the better. Hostilities would help legitimize the second phase of the operation: The non-treaty Lakotas were to be given an impossibly short deadline to report to the reservation; the Indian Bureau was to manufacture complaints against them, and Sheridan was to make ready for his favorite form of warfare, a winter campaign against unsuspecting Indian villages.

The Army’s commander had no ink-ling of the intrigue until November 13, when Sherman asked Sheridan why he hadn’t yet filed his annual report. Sheridan’s reply, also at the Library of Congress, rounds out the conspiracy: “After my return from the Pacific Coast,” Sheridan wrote insouciantly, “I was obliged to go east to see...about the Black Hills, and my report has thus been delayed.” Rather than elaborate on the war plan, Sheridan simply enclosed a copy of his orders to Terry, suggesting to Sherman they “had best be kept confidential.”

Sherman exploded. How could he be expected to command, he wrote to his brother, Senator John Sherman, “unless orders come through me, which they do not, but go straight to the party concerned?” He vowed never to return to the capital unless ordered.

**********

To manufacture complaints against the Lakotas, the Grant administration turned to an Indian Bureau inspector named Erwin C. Watkins, who had just come back from a routine tour of the Montana and Dakota Indian agencies. Watkins’ official duties were administrative, such as auditing Indian agents’ accounts. But in reporting on his tour, he went well beyond the scope of his authority to describe the behavior of the non-treaty Lakotas, though it is unlikely he ever saw one.

The Watkins report singled them out as “wild and hostile bands of Sioux Indians” who “richly merit punishment for their incessant warfare, and their numerous murders of settlers and their families, or white men wherever found unarmed.” Most offensive, they “laugh at the futile efforts that have thus far been made to subjugate them [and] scorn the idea of white civilization.” Without ever mentioning the Fort Laramie Treaty, the report concluded that the government should send a thousand soldiers in to the Unceded Territory and thrash the “untamable” Lakotas into subjection.

Watkins had long worked in Zachariah Chandler’s Michigan political machine, and he had served under Sheridan and Crook in the Civil War. His report, dated November 9, encapsulated Sheridan’s and Crook’s views. It is difficult to escape the suspicion that the conspirators had ordered Watkins to fabricate his report, or even wrote it themselves.

While leaking the Watkins report—it made headlines in a handful of papers—the conspirators obscured their war preparations. At Crook’s headquarters in Wyoming Territory, rations and ammunition were being stockpiled, pack trains prepared, troops marshaled in from outlying forts. Something clearly was afoot, but Crook and his staff declined to discuss it with the local press.

The Chicago Inter Ocean correspondent who had stoked the gold frenzy, William E. Curtis, actually came close to exposing the plot. After sounding out his Army contacts, Curtis told his readers just five days after the White House meeting, “The roving tribes and those who are known as wild Indians will probably be given over entirely to the military until they are subdued.” The precise identity of his source is unknown, but when Curtis took the matter up with the high command, a senior officer dismissed talk of war as “an idle fancy of a diseased brain.” Curtis didn’t press the matter, and an Inter Ocean correspondent in the field concluded that war was unlikely for the simple reason that Lakota Indian agents told him, truthfully, that the Indians had no wish to fight.

On December 3, Chandler set in motion the first phase of the scheme. He directed the Indian Bureau to inform Sitting Bull and the other non-treaty chiefs that they had until January 31, 1876, to report to the reservation; otherwise they would be considered “hostile,” and the Army would march against them. “The matter will in all probability be regarded as a good joke by the Indians,” Sheridan wrote to Sherman, who had lost interest in what his subordinate was up to.

By then the Lakotas were snowbound in villages scattered throughout the Unceded Territory. Their attitude hadn’t changed; they had no truck with the wasichus so long as they stayed off Lakota land, which their chiefs had no intention of surrendering. Their response to Chandler’s ultimatum was unthreatening and, from an Indian perspective, quite practical: They appreciated the invitation to talk but were settled in for the winter; when spring arrived and their ponies grew strong, they would attend a council to discuss their future.

Indian agents dutifully conveyed the message to Washington—where Edward Smith, the commissioner of Indian affairs, buried it. Sticking to the official line secretly scripted in November, he declared that the Lakotas were “defiant and hostile”—so much so that he saw no point in waiting until January 31 to permit the Army to take action against them. Interior Secretary Chandler, his superior, duly endorsed the fiction. “Sitting Bull still refuses to comply with the directions of the commissioners,” he told Belknap, and he released authority for the non-treaty Lakotas to the war secretary, for whatever action the Army deemed appropriate.

Sheridan had a green light. On February 8, he ordered Terry and Crook to begin their campaign.

The winter operations were a bust. Terry was snowbound. Crook mistakenly attacked a village of peaceable Cheyennes, which only alienated them and alerted the non-treaty Lakotas. Worse, the Army’s stumbling performance hardly persuaded the reservation chiefs that they needed to cede the Black Hills.

That spring, thousands of reservation Indians migrated to the Unceded Territory, both to hunt buffalo and to join their non-treaty brethren in fighting for their liberty, if necessary. The Army launched an offensive, with columns under Crook, Terry and Col. John Gibbon converging on the Lakota country. The Indians eluded Gibbon. Crook was bloodied at the Battle of the Rosebud on June 17 and withdrew to lick his wounds. Eight days later, some of Terry’s men—the 7th Cavalry, under Custer—set upon the Lakotas and their Cheyenne allies at the Little Bighorn and paid the ultimate price for Grant’s perfidy.

**********

Then came the cover-up. For eight months, Congress had paid little heed to events in the Lakota country. Only after the Little Big Horn debacle did Congress question the war’s origins and the government’s objectives.

The conspirators had prepared for congressional scrutiny. The new secretary of war, J. Donald Cameron, took just three days to submit a lengthy explanation, together with Watkins’ report and 58 pages of official correspondence on the subject. Absent was Sheridan’s incriminating order to Terry from November 9, 1875.

Military operations, Cameron assured Congress, targeted not the Lakota nation, only “certain hostile parts”—in other words, those who lived in the Unceded Territory. And the Black Hills, Cameron attested, were a red herring: “The accidental discovery of gold on the western border of the Sioux reservation and the intrusion of our people thereon, have not caused this war, and have only complicated it by the uncertainty of numbers to be encountered.” If Cameron were to be believed, the war lust of young Lakotas had brought on the conflict.

Certainly many congressmen recognized Cameron’s chicanery for what it was. But with the nation’s press clamoring for retribution after the Little Bighorn, they dared not dispute the administration’s line. Congress gave the Army carte blanche to conduct unremitting war. By May 1877, the Lakotas had been utterly defeated.

Nearly everyone seemed content to blame them for the conflict. A singular dissenting voice was George W. Manypenny, a reform-minded former Indian Bureau commissioner. He surmised that “the Sioux War of 1876, the crime of the centennial year, [was] inaugurated” at the White House in November 1875. But he was dismissed as an Indian apologist, and no one took his allegations seriously.

In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the Lakotas were entitled to damages for the taking of their land. The sum, uncollected and accruing interest, now exceeds $1 billion. The Lakotas would rather have the Black Hills.

Related Reads

The Earth Is Weeping: The Epic Story of the Indian Wars for the American West