Understanding Detroit’s 1967 Upheaval 50 Years Later

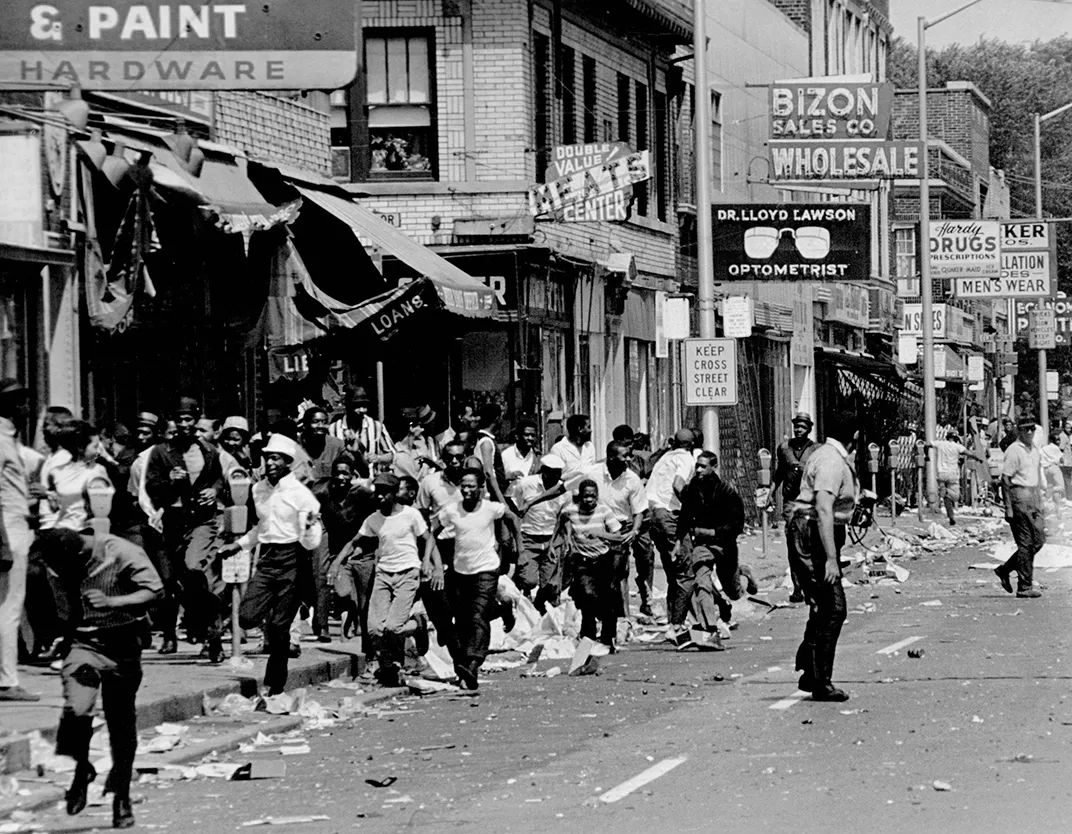

For five days in July, the Motor City was under siege from looters and soldiers alike

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6d/84/6d84c95b-e8bc-41dc-8b69-f59f4735fd72/detroit-fire.jpg)

The summer of 1967 was sultry in the United States, with temperatures in the 80s and 90s for weeks on end, forcing people outdoors—and sometimes into violent conflagrations.

Thousands of protestors agitated against the Vietnam War; meanwhile, almost 150 cities saw police confrontations in African-American communities. And on July 23, starting at 3 a.m., Detroit convulsed in the largest riot the country had seen since the New York draft riots in 1863. Looters prowled the streets, arsonists set buildings on fire, civilian snipers took position from rooftops and police shot and arrested citizens indiscriminately.

At the end of five days of unrest, 43 people were dead, hundreds more were injured, more than 7,000 had been arrested and 2,509 buildings were destroyed by fire or looting. It took troops from the U.S. Army and the National Guard to finally restore peace in the city.

“There were riots all around—it wasn’t just Detroit,” city resident William Pattinson told the Detroit 1967 Oral and Written History Project. “You felt like, for the first time, this country isn’t going to make it. It was the closest I ever felt that our government was going to fall apart.”

Making sense of the Detroit riot—alternately called the “uprising,” or the “rebellion”—is the work of a lifetime. “It’s hugely complicated, many-layered, very deep, and in Detroit’s history as one of those singular events, much like 9-11, where everybody remembers it,” says Joel Stone, a senior curator with the Detroit Historical Society, which manages the Detroit History Museum. The importance of capturing that nuance is why they launched the oral history project. It has collected interviews from 500 Detroiters so far.

For those who weren’t in the city during the upheaval, but who want to understand the history—perhaps in anticipation of (or after watching) Kathryn Bigelow’s new film, Detroit—here’s a guide to how the scene unfolded and why the issues that lay at the center of the event still hold significance today.

What sparked the riot?

First, the short answer: In the early hours of Sunday, July 23, members of the (overwhelmingly white) Detroit Police Department raided an illegal nightclub—called a “blind pig”—in a popular (and overwhelmingly black) part of the city, on 12th Street. Among the revelers arrested by police were two black veterans recently returned from the Vietnam War. A crowd gathered on the street to watch the men being carried away, and as the police left, teenager William Walter Scott III launched a bottle at the officers (Scott later wrote a memoir about being labeled as the man who started the riot). Over the next few hours, tensions escalated as citizens looted stores around the neighborhood. The police struggled to defuse the situation, as only 200 of Detroit's 4,700 officers were on duty at the time. Over 20 community leaders including ministers and union leaders tried to break up the rioters, but were unsuccessful, writes Hubert G. Locke in The Detroit Riot of 1967. The looting only spread from there.

The long answer: A number of factors were at play. Despite being hailed as a “model city” by media pundits and politicians for the progressive politics of its white mayor, Jerome Cavanagh, African-American residents suffered from much of the same discrimination in Detroit as they did elsewhere. Inequities in housing, jobs and education were rampant, Stone says, as were instances of police brutality. Just a month earlier, Vietnam veteran Daniel Thomas had been murdered by a crowd of white men in Rouge Park, a city park surrounded by white-only neighborhoods. The assailants also threatened to rape Thomas’s pregnant wife.

“I’ve gone around and studied the Civil Rights Movement in the South and I’ve come to feel that no place exceeds Detroit in separation on the basis of race,” says Christopher Wilson, a historian at the National Museum of American History. Wilson was born in Detroit just days after the riot ended; his mother and older sister were huddled in the basement throughout the ordeal while his father protected their house. “The riot was so traumatic for my family and the neighborhood we lived in. They always thought of it as something really destructive. But I started to have an understanding later of where the anger came from.”

What contributed to this anger?

While many systemic problems contributed to feelings of frustration among Detroit’s African-American communities, police confrontations were the overwhelming issue. In Violence in the Model City, historian Sidney Fine writes that a field survey from before the riot found that 45 percent of Detroit police officers working in black neighborhoods were “extremely anti-Negro” and an additional 34 percent were “prejudiced”—more than three-fourths of officers had antagonistic attitudes toward the people they were meant to protect.

“There were these notorious police squads, and the ‘Big Four’ squad car with four officers that would pull over black men standing on street corners and harass them, beat them sometimes,” Wilson says. “I remember an editorial about a supposed purse-snatcher running away from the police and he was shot in the back.”

Even inside Detroit’s police department, discrimination against African-American officers led to tense and nearly deadly encounters. Isaiah “Ike” McKinnon, who later became police chief and deputy mayor, was on duty during the riot. After heading home from one shift, still dressed in his uniform, he was pulled over by two white officers who told him, “Tonight you’re going to die, n****r.” They then proceeded to shoot at him as he drove off. “It hit me in terms of, if they shot at me, a fellow police officer, what are they going to do to other people in the street, the city?” McKinnon told the Detroit History Museum’s oral history project.

How did the federal government respond?

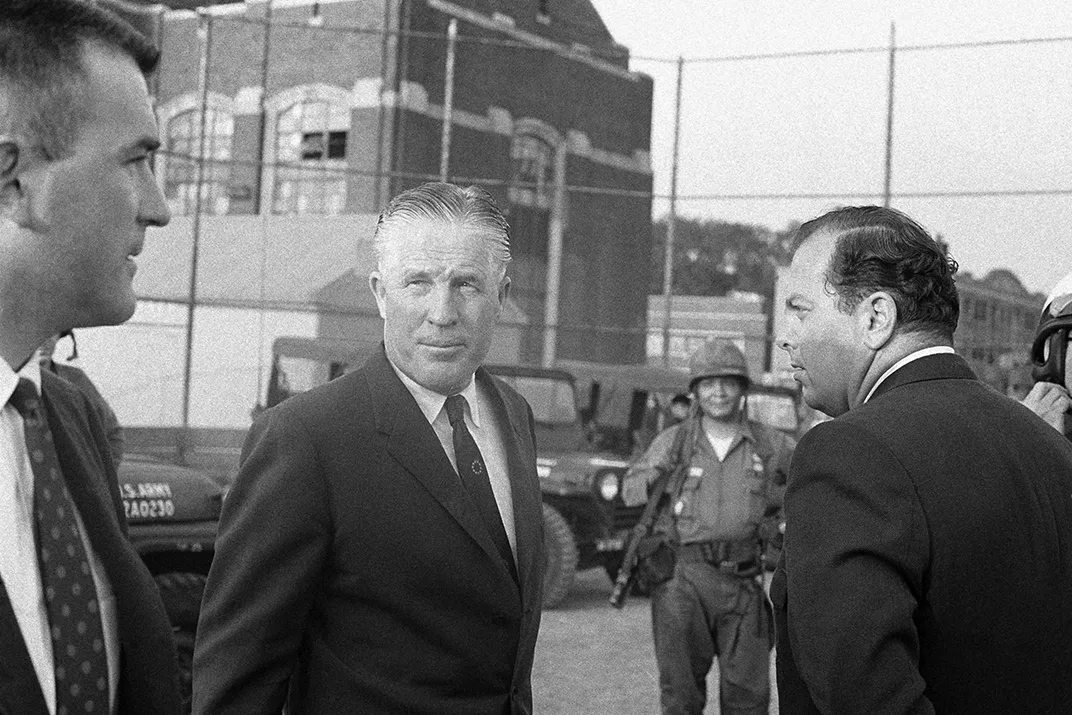

Although it briefly seemed that a “quarantine” of the initial riot zone had succeeded in sealing off the looters and arsonists, the Detroit police were soon overwhelmed by the spreading carnage. On July 24, Michigan Governor George Romney called the Michigan National Guard to the city. By July 26, 12 square miles of the city were on fire. At that point, Mayor Cavanagh and the governor appealed to President Lyndon Johnson to send federal troops, and he dispatched two brigades from the Army’s Airborne Divisions. Together, the combined firepower of the troops managed to quell the violence by July 29. The Michigan National Guard demobilized on August 2.

But the situation may have been resolved more rapidly if not for the political machinations of Cavanagh (a Democrat), Romney (a Republican) and Johnson (also a Democrat), Stone says. “You had three guys who wanted to be president. One of them was, one of them [Romney] had a good shot at it, one [Cavanagh] was a young upstart. In the case of the mayor and governor, [their antagonism] delayed things slightly, and with the governor and president, it delayed [federal aid] at least 24 hours. Newark [which had a similar riot] had three times as many policemen per square mile and three times as many firemen. Their event was shorter, had half the number of injuries, and 20 percent the number of arrests. So arguably, if we’d been able to move faster, yes, it would’ve been less serious.”

How do the events of the movie Detroit fit in to the broader story?

Detroit depicts a single event in the larger chaos of the riots. Around 1 a.m. on July 26, Detroit police officers, National Guardsmen and State Police poured into the Algiers Motel, where seven black men and two white women had been holed up playing dice and smoking cigarettes. Two hours later, the police left the building, with three dead young men. The survivors had been beaten, and had to call the families themselves, as police never filed a report of the incident. For John Hersey, who wrote The Algiers Motel Incident in 1968, the murders illustrated

“All the mythic themes of racial strife in the United States: the arm of the law taking the law into its own hands; interracial sex; the subtle poison of racist thinking by ‘decent’ men who deny they are racists; the societal limbo into which, ever since slavery, so many young black men have been driven in our country; ambiguous justice in the courts; and the devastation that follows in the wake of violence as surely as ruinous and indiscriminate flood after torrents.”

Although several trials were later held, all officers involved in the shootings were acquitted of all charges. For defense attorney Norman Lippitt, who helped the men win a not-guilty verdict, the “most significant break” in the case was the all-white jury, reported NPR.

What happened after the riot ended?

Politicians at different levels of government promoted the formation of bipartisan coalitions, and set out to understand what had caused the riots in Detroit and elsewhere. Using an executive order, President Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders to investigate the causes of rioting, while Governor Romney and Mayor Cavanagh recommended the creation of New Detroit, a coalition to promote racial justice.

“Initially the stores that were burned didn’t rebuild, the neighborhoods were left as they were, federal money went to neighborhoods that were relatively stable,” Stone says. “On the plus side, I think it was a wakeup call in the black community and the white community. It certainly increased the call in the black community for more self-reliance.”

The city elected its first black mayor Coleman Young, in 1974, and new policies pushed the police department to become more integrated.

For Wilson, who grew up in a post-riot Detroit, the difference in policing was particularly marked. “The feeling that [police officers] were going to harass you or be violent with you, if I’d grown up before the riot that would’ve been common knowledge. But that just wasn’t part of my childhood.”

“The one way my neighborhood didn’t recover,” Wilson adds, “was by the time I have memories, there weren’t any white people left.” White flight to the suburbs, which had started decades earlier, intensified after 1967. While Detroit’s population shrunk 20 percent from 1950 to 1960, the number of white people exiting the city doubled to 40,000 in 1967, then doubled again the next year.

“I think many of the suburban people thought the riots took Detroit away from them,” Wilson says. “I think there’s a feeling of resentment on that account, because the violence that they feel was completely unjustified stole Detroit from them.”

Why do some call it a “riot,” while others say it was a “rebellion”?

Like so many aspects of what happened in Detroit, nomenclature is all a matter of perspective. “Riot connotes a fault that falls on the people involved in the uprising,” Stone says. “And I think there came to be an understanding that the people who were on the street, burning, looting and sniping had some legitimate beef. It really was a pushback—or in some people’s terms, a ‘rebellion,’—against the occupying force that was the police.”

Wilson agrees that it’s a political question. “There are riots in American history that we praise and glorify, like the Boston Tea Party. Smithsonian museums are filled with glorifications of certain acts of violence—when we think it’s the right thing to do.” Even though Wilson doesn’t think violence should be used to solve political problems, he says, “I’ve always understood the feeling of the people on 12th Street who felt like they were being harassed and further brutalized.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)