WANTED: The Limping Lady

The intriguing and unexpected true story of America’s most heroic—and most dangerous—female spy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/spy_hall-painting_388.jpg)

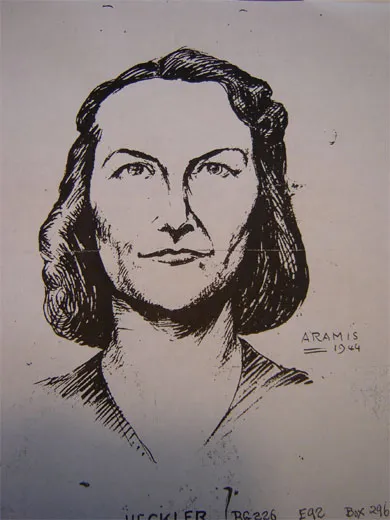

The Nazi secret police were hunting her. They had distributed "wanted" posters throughout Vichy France, posters with a sketch of a sharp-featured woman with shoulder-length hair and wide-set eyes, details provided by French double agents. They were determined to stop her, an unknown "woman with a limp" who had established resistance networks, located drop zones for money and weapons and helped downed airmen and escaped POWs travel to safety. The Gestapo's orders were clear and merciless: "She is the most dangerous of all Allied spies. We must find and destroy her."

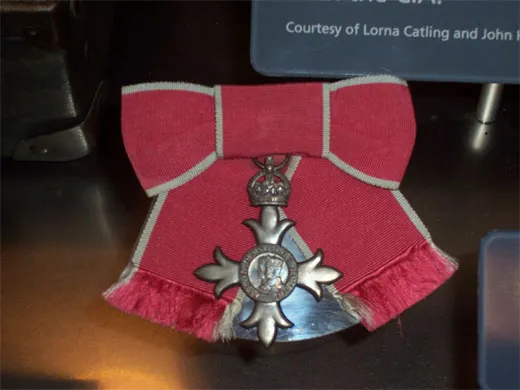

Virginia Hall, the daughter of a wealthy family in Baltimore, Maryland, wanted to become a United States Foreign Service officer, but was turned down by the State Department. Instead, she became one of World War II's most heroic female spies, saving countless Allied lives while working for both Britain and the United States. Now, more than two decades after her death at age 78, Hall's extraordinary actions are in the spotlight once again. In December, the French and British ambassadors honored her at a ceremony in Washington, DC attended by Hall's family. "Virginia Hall is a true hero of the French Resistance," wrote French President Jacques Chirac in a letter read by the French ambassador. The British ambassador presented Hall's family with a certificate to accompany the Order of the British Empire medal Hall received from King George VI in 1943.

Despite their relentless efforts, the Gestapo never captured Hall, who was then working for the British secret paramilitary force Special Operations Executive (SOE). The SOE had recruited her after she had a chance meeting with an SOE member on a train out of France soon after the country fell to the Nazis in 1940. In joining, she became the SOE’s first female operative sent into France. For two years, she worked in Lyon as a spy, initially under the guise of a stringer for the New York Post, then, after the United States entered the war, she was forced to go underground. She knew that as an enemy she would be tortured and killed if she were caught, but she continued her work for another 14 months.

Hall fled France only after the Allies landed in North Africa and Nazis started flooding the country. To escape, she had to cross the Pyrenees mountains by foot into Spain, a difficult task for a woman who had lost her left leg in a hunting accident years before and used an artificial leg she had nicknamed "Cuthbert." As her guide led her across the frozen landscape in mid-winter, she transmitted a message to SOE headquarters in London saying she was having trouble with her leg. The reply: "If Cuthbert is giving you difficulty, have him eliminated."

After the grueling trek, Hall arrived in Spain without entry papers. Officials immediately threw her into Figueres Prison, where she remained for six weeks. She was released only after a freed inmate smuggled a letter written by Hall to the American consul in Barcelona, alerting them to her situation.

She spent the next four months in Madrid working undercover as a correspondent for the Chicago Times before asking SOE headquarters for a transfer. "I thought I could help in Spain, but I’m not doing a job," Hall wrote, as noted in Elizabeth P. McIntosh's book Sisterhood of Spies. "I am living pleasantly and wasting time. It isn’t worthwhile and after all, my neck is my own. If I am willing to get a crick in it, I think that’s my prerogative."

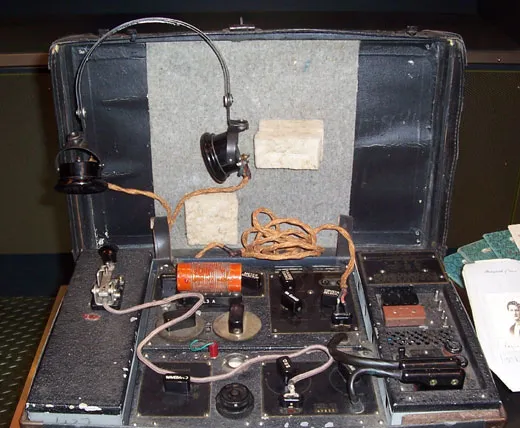

While the SOE trained her as a wireless radio operator in London, she learned of the newly formed Office of Strategic Services (OSS), America's wartime precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. She quickly joined, and, at her request, the OSS sent her back into occupied France, an incredibly dangerous mission given her high profile. Unable to parachute in because of her artificial leg, she arrived in France by British torpedo boat.

Her assignment was as a radio operator in the Haute-Loire region of central France. To avoid detection, she disguised herself as an elderly milkmaid, dying her hair grey, shuffling her feet to hide her limp and wearing full skirts to add weight to her frame. While undercover, she coordinated parachute drops of arms and supplies for resistance groups and reported German troop movements to London. By staying on the move, camping out in barns and attics, she was able to avoid the Germans who were desperately trying to track her radio signals.

D-Day loomed. Everyone, including the Germans, knew an Allied landing was imminent, but they didn't know when or where it would take place. Hall armed and trained three battalions of French resistance fighters for sabotage missions against the retreating Germans. As part of the resistance circuit, Hall was ready to put her team into action at any moment. In her final report to headquarters, Hall stated that her team had destroyed four bridges, derailed freight trains, severed a key rail line in multiple places and downed telephone lines. They were also credited with killing some 150 Germans and capturing 500 more.

Soon after the war ended, President Harry Truman wished to present Hall with the Distinguished Service Cross, the second highest U.S. military award for bravery. Hall, however, requested that Maj. Gen. William J. Donovan, founder of the OSS, give her the medal in a small ceremony in his office, attended only by her mother.

"She always avoided publicity," Hall's niece, Lorna Catling, said recently from her home in Baltimore. “She would say, 'It was just six years of my life.'"

Hall also rarely talked about her clandestine work, even to her family. "I do remember one letter [Hall] sent home during the war," Catling says. "She said that the Germans had caught some people and hung them up by a butcher's hook. It was a terrifying letter."

"I think she was concerned about capitalizing on her experiences," says Judith L. Pearson, author of Wolves at the Door, a recent biography of Hall. "People she knew died. She felt obligated to them and wanted to be respectful of their deaths."

Peter Earnest, executive director of the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC and a 35-year veteran of the CIA, says Hall was an extraordinarily brave woman. The museum houses a permanent exhibit on Hall, which includes the suitcase radio she used to send messages to London in Morse code, along with the British Empire medal and some of her identification papers. Her Distinguished Service Cross resides at the CIA Museum in McLean, Virginia.

"She was in imminent danger of being arrested virtually the whole time that she was in France," says Earnest. "She was very aware of the consequences if the Germans picked her up."