War and Peace of Mind for Ulysses S. Grant

With the help of his friend Mark Twain, Grant finished his memoirs—and saved his wife from an impoverished widowhood—just days before he died

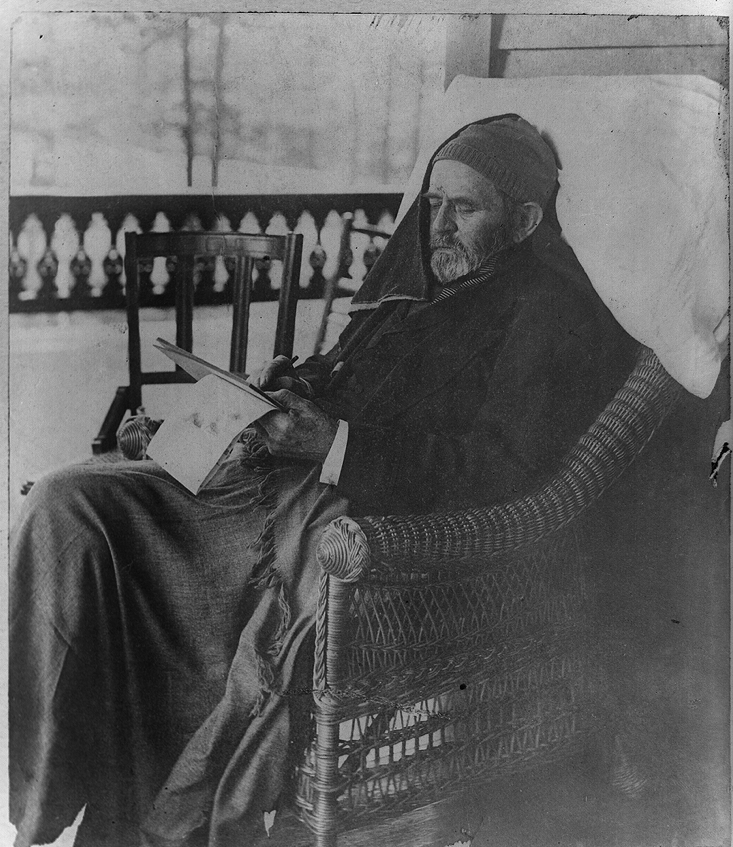

![]()

Ulysses S. Grant working on his memoirs just weeks before his death in 1885. Photo: Library of Congress

After serving two terms as president, Ulysses S. Grant settled in New York, where the most famous man in America was determined to make a fortune in investment banking. Wealthy admirers like J. P. Morgan raised money to help Grant and his wife, Julia, make a home on East 66th Street in Manhattan, and after two decades at war and in politics, the Ohio-born son of a tanner approached his 60s aspiring to join the circles of the elite industrialists and financiers of America’s Gilded Age.

But the Union’s preeminent Civil War hero had never been good at financial matters. Before the Civil War he’d failed at both farming and the leather business, and on the two-year, round-the-world tour he and Julia took after his presidency, they ran out of money when Grant miscalculated their needs. Their son Buck had to send them $60,000 so they could continue on with their travels. In New York, in the spring of 1884, things were about to get worse.

After putting up $100,000 in securities, Grant became a new partner, along with Buck, in the investment firm of Grant and Ward. In truth, Grant had little understanding of finance, and by May 1884, he had seen yet another failure, this one spectacular and publicized in newspapers across the country. Ferdinand Ward, his dashing and smooth-talking partner—he was only 33 but known as the “Young Napoleon of Wall Street”—had been running a Ponzi scheme, soliciting investments from Grant’s wealthy friends, speculating with the funds, and then cooking the books to cover his losses.

On May 4, Ward told Grant that the Marine National Bank was on the verge of collapse, and unless it received a one-day cash infusion of $150,000, Grant and Ward would be wiped out, as most of their investments were tied up with the bank. A panic, Ward told him, would most likely follow. Grant listened intently, then paid a visit to another friend—William H. Vanderbilt, richest man in the world, president of the Pennsylvania Railroad.

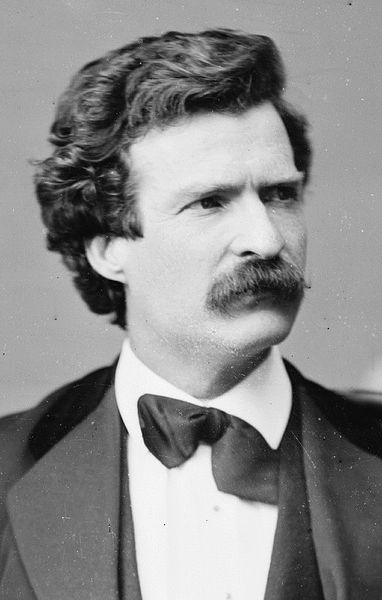

Grant’s friend Mark Twain published Grant’s memoirs just months after the former president’s death. Photo: Wikipedia

“What I’ve heard about that firm wouldn’t justify me in lending it a dime,” Vanderbilt told him. The tycoon then made it clear that it was his relationship with Grant that mattered to him most, and he made a personal loan of $150,000, which Grant promptly turned over to Ward, confident the crisis would be averted. The next morning, Grant arrived at his office only to learn from his son that both Marine National and Grant and Ward were bankrupt. “Ward has fled,” Buck told him. “We cannot find our securities.”

Grant spoke glumly to the firm’s bookkeeper. “I have made it a rule of life to trust a man long after other people gave up on him,” he said. “I don’t see how I can trust any human being ever again.”

As news of the swindle and Grant’s financial demise spread, he received a great deal of public sympathy, as well as cash donations from citizens who empathized and were grateful for his service to the nation. “There is no doubt,” one man told a reporter at the time, “that Gen. Grant became a partner to give his son a good start in life. He gave him the benefit of his moderate fortune and the prestige of his name, and this is his reward.”

Ward didn’t get very far. He served a six-year sentence for fraud at Sing Sing Prison, but he left Grant in ruin. After all was said and done, the investment firm had assets of just over $67,000 and liabilities approaching $17 million. Yet Grant would not accept any more help from his friends—especially Vanderbilt, who offered to forgive the loan. With no pension, Grant sold his home and insisted that Vanderbilt take possession of his Civil War mementos—medals, uniforms and other objects from Grant’s famous past. Vanderbilt reluctantly accepted them and considered the debt settled. (With Julia Grant’s consent, Vanderbilt later donated the hundreds of historical items to the Smithsonian Institution, where they remain today.)

Bankrupt and depressed, Ulysses S. Grant soon received more bad news. Pain at the base of his tongue had made it difficult for the 62 year-old to eat, and he visited a throat specialist in October of that year. “Is it cancer?” Grant asked. The physician, observing carcinoma, remained silent. Grant didn’t need to know more. The physician immediately began treating him with cocaine and a derivative of chloroform. Aware that his condition was terminal, and that he had no other way of providing for his family, Grant determined there was no better time to write his memoirs. He left the doctor’s office to meet with a publisher at the Century Co., who immediately offered a deal. As a contract was being drawn up, Grant determined to get to work on his writing and to cut back on cigars. Just three a day, his doctors told him. But shortly after his diagnosis, Grant received a visit from his old friend Mark Twain. The visit just happened to occur on the November day that Grant was sitting with his eldest son, Fred, about to sign the Century contract.

Twain had made a considerable amount of money from his writing and lecturing but, was, once again, in the midst of his own financial troubles. He’d suffered a string of failed investments, such as the Paige Compositor—a sophisticated typesetting machine that was, after Twain had put more than $300,000 in it, rendered obsolete by the Linotype machine. And he had a manuscript that he’d been laboring over for almost a decade in fits and starts. Twain had been after Grant to write his memoirs for years, and he knew a publishing deal was in the works. Grant told Twain to “sit down and keep quiet” while he signed his contract, and Twain obliged—until he saw Grant reach for his pen. “Don’t sign it,” Twain said. “Let Fred read it to me first.”

When Twain heard the terms, he was appalled: The royalty rate was only 10 percent, too low for even an unknown author, let alone someone of Grant’s stature. He said he could see to it that Grant would get 20 percent if he would hold off on signing the Century contract. Grant replied that Century had come to him first and he felt “honor-bound” to keep to the deal. Then Twain reminded his host that he had offered to publish Grant’s memoirs years before. Grant acknowledged that that was true, and ultimately allowed Twain to persuade him to sign with what would become Charles L. Webster & Co., the publisher Twain formed with his niece’s husband. Out of pride, Grant refused a $10,000 advance from his friend, fearing his book might lose money. He agreed, however, to accept $1,000 for living expenses while he wrote. Twain could only shake his head. “It was a shameful thing,” the author later recounted, “that a man who had saved his country and its government from destruction should still be in a position where so small a sum—$1,000—could be looked upon as a godsend.”

Even as he sickened over the next year, Grant wrote and, when too tired for that, dictated at a furious pace each day. On the advice of doctors, he moved into a cottage in the fresh Adirondack air at Mount McGregor in upstate New York. As word of his condition spread, Civil War veterans made pilgrimages to the cottage to pay their respects.

Twain, who was closely supervising Grant’s writing, also finally finished his own manuscript. He published it under the title The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in the United States in February 1885. It was a huge and immediate success for Charles L. Webster and Co., and it has done rather nicely ever since.

On July 20, 1885, Grant—his neck swollen, his voice reduced to a pained whisper—deemed his manuscript complete. Unable to eat, he was slowly starving to death. Grant’s doctors, certain that his will to finish his memoir was the only thing keeping him alive, prepared for the end. It came on the morning of July 23, with Julia and his family beside him. Among the last words in his memoirs were the words that would eventually be engraved on his tomb: “Let us have peace.”

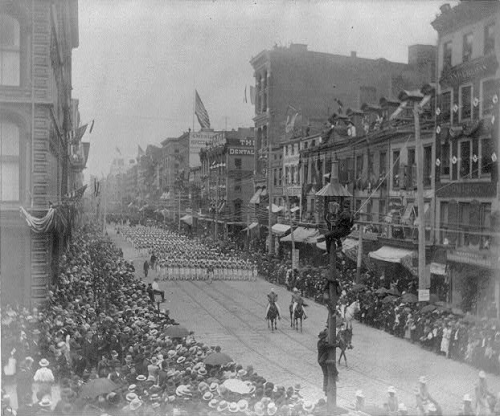

Twenty years before, Grant had stood at Abraham Lincoln’s funeral and wept openly. Grant’s Funeral March, through New York City on August 8, 1885, was the longest procession in American history to the time, with more than 60,000 members of the United States military marching behind a funeral car bearing Grant’s casket and drawn by 25 black stallions. Pallbearers included generals from both the Union and Confederate armies.

Earlier that year, Webster & Co. had begun taking advance orders on what was to be a two-volume set of Grant’s memoirs. Published that December, the Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant was an immediate success; it ultimately earned Julia Grant royalties of about $450,000 (or more than $10 million today), and today some scholars consider it one of the greatest military memoirs ever written. Between that and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Charles L. Webster & Co. had quite a year.

Sources

Books: Charles Bracelen Flood, Grant’s Final Victory: Ulysses S. Grant’s Heroic Last Year, De Capo Press, 2012. Mark Perry, Grant and Twain: The Story of a Friendship that Changed America, Random House, 2004. Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, Charles L.Webster & Company, 1885-86.

Articles: “Pyramid Schemes Are as American as Apple Pie,” by John Steele Gordon, The Wall Street Journal, December 17, 2008. “A Great Failure,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 7, 1884. “Grant’s Funeral March,” American Experience, PBS.org. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/grant-funeral/ ”The Selling of U.S. Grant,” by Bill Long, http://www.drbilllong.com/CurrentEventsVI/GrantII.html “Read All About Geneseo’s Dirty Rotten Scoundrel,” by Howard W. Appell, Livingston County News, May 16, 2012. “Museum to help spotlight Grant’s life, legacy,” by Dennis Yusko, Albany Times Union, November 23, 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/gilbert-king-240.jpg)