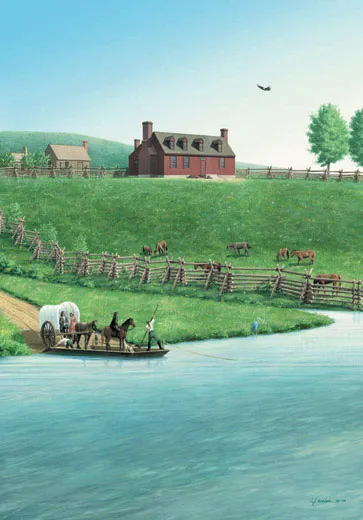

Washington’s Boyhood Home

Archaeologists have finally pinpointed the Virginia house where our first president came of age

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/digswashington_sept08_631.jpg)

Suffice it to say that the idea of historic preservation hadn't quite caught on by the mid-19th century. As Union soldiers decamped on the banks of the Rappahannock River before their offensive on Fredericksburg, Virginia, in December 1862, they knew they were on farmland that had once belonged to George Washington's family.

Some of them sent cherry pits home in the mail, in reference to the legendary, if apocryphal, felled tree, while others lamented that the Civil War raged even at the homestead of the nation's father.

Though the soldiers apparently appreciated the significance of where they were, they methodically tore down the house they believed was Washington's "for fuel and to assist in making comfortable the headquarters of the nearest regiments," as William Draper of the Massachusetts Infantry later recalled.

How times have changed. For the past seven years at Ferry Farm (so named for the ferry that once ran to Fredericksburg), archaeologists David Muraca and Philip Levy have been leading an effort to pinpoint the location of Washington's boyhood home. They hope the understanding they might gain from excavating the house in which our first president came of age will not only shed light on a dimly understood time in his life but will also inform the structure's eventual restoration. Finally, this past July, after fruitless digs in two other locations at the site, Muraca and Levy announced they had indeed found the foundation of the farmhouse, perched atop a bluff that sweeps down to the Rappahannock. (The house the Union soldiers tore down was actually built by another owner around 1850.)

"Historians sort of pick George up at age 20," says Levy, of the University of South Florida. He is standing at the dig site, where a small army of interns and volunteers wearing "I Dig George" T-shirts are sifting soil. "Basically, the first ten pages of any Washington biography describe his childhood—and the remaining 400 pages are devoted to his time as surveyor, soldier and finally president." You can't blame the biographers for this oversight; very few documents from Washington's youth survive. "This site is the best chance to look at a detailed text," says Levy. "This is the best text we're going to get."

As if finding that text weren't difficult enough, deciphering it could prove even tougher. In their years of digging, the archaeologists have uncovered the scars and traces of more than three centuries of human activity, a sort of palimpsest written in dirt and debris. "This is the hardest site I've ever worked on," says Muraca, director of archaeology for the George Washington Foundation. Five different farmsteads have occupied the Washington property since the 1700s—Washington's home was the second; the house torn down by Union soldiers was the third. A trench dug by those soldiers cuts right through the correct house's foundation at one angle, while a 20th-century drainage trench comes at it from another. What's more, each farmhouse had a number of associated outbuildings—quarters for slaves, dairy, smokehouse and kitchen. Thus, despite the quaint country road lined with Virginia fences and the river below, this is essentially "as complex as an urban site," says Levy.

Washington's biographers—or at least, those who have bothered to sift truth from legend—have been able to paint his boyhood only in broad brush strokes. We know his father, Augustine, moved the family to the site in 1738, when George was 6, probably to be closer to the iron furnace he managed. We know George's baby sister Mildred died in 1740, and two letters from family acquaintances allude to a fire on Christmas Eve that same year. And we know Washington's father died in 1743, jeopardizing the family's finances and rendering a proper English education out of reach for George, whose mother never remarried. The future president's budding career as a surveyor and soldier kept him increasingly away from Ferry Farm until 1754, when he took over as the administrator of his late brother's estate, Mount Vernon, at age 22. Beyond that, much has been guesswork.

The data being sifted from the new dig—half a million artifacts (including nails, pottery and even broken eggshells)—are adding to this knowledge. For instance, historians had been uncertain as to the extent of that Christmas Eve house fire. Muraca, Levy and their team found blistered ceramics and burnt plaster in one part of the house, but not elsewhere—indicating that while the fire must have been disruptive, it did not require massive rebuilding. But many of the artifacts raise more questions than answers: for instance, the archaeologists found a ceramic shard and oyster shell hidden in a crevice in the cellar's stone wall. A child's prank? A superstitious totem? Muraca shrugs. Other artifacts are simply exciting to behold, even if they are less mysterious. The excavators found the smoke-stained bowl of a small clay pipe, decorated with a Masonic crest. Since Washington joined the Freemasons in 1753, it is no great leap to imagine the young man stuffing tobacco into that very pipe.

The project at Ferry Farm is but one of several Washington-related sites excavated in recent years. In Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, ongoing excavation has revealed that the Continental Army under Washington's command was more active—preparing for the next clash with the British—than had been previously supposed. Continuous excavation at Mount Vernon shows Washington's entrepreneurial side. After leaving the White House, he entered the whiskey business in 1797, soon distilling up to 11,000 gallons a year. And an excavation last year of the first presidential house in Philadelphia revealed a passageway used by Washington's slaves. "George Washington is hot right now, archaeologically," says Levy.

Back at Ferry Farm, Muraca and Levy are extending the excavation to search for more outbuildings, and they anticipate collecting another half-million artifacts in the next few years. "If we do our job right, the Washington biographies will change," says Muraca.

Washington biographer Richard Brookhiser, who has written three books on the man, welcomes the information gleaned from recent digs, though he says considerable interpretive work remains to be done. "Facts still require us to think about them," he says. Brookhiser puzzles over the elaborate Wedgwood tea service the Washingtons purchased after the Christmas fire and two deaths dealt harsh blows to the family. "What did the Wedgwood mean?" Brookhiser muses. "A surprising level of prosperity? Or a grim effort to hang onto the signs of gentility at all costs?"

Ron Chernow, a biographer of Alexander Hamilton now at work on a biography of Washington, says that at the very least the discovery should help humanize the founding father by giving us "valuable shading and detail" and lifting "the story out of the realm of myth."

David Zax is a freelance writer based in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/david-zax-240.jpg)