Wayne B. Wheeler: The Man Who Turned Off the Taps

Prohibition couldn’t have happened without Wheeler, who foisted temperance on a thirsty nation 90 years ago

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Prohibition-Detroit-1920-631.jpg)

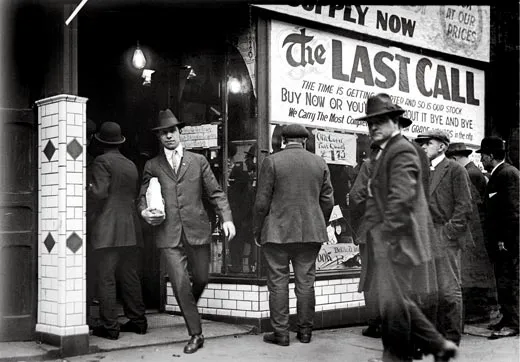

On the last day before the taps ran dry, the streets of San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered just before transporting their contents would become illegal. Across the country in New York City, Gold’s Liquor Store placed wicker baskets filled with its remaining inventory on the sidewalk; a sign read, “Every bottle, $1.”

On the first day of Prohibition, January 17, 1920, Bat Masterson, a 66-year-old relic of the Wild West now playing out the string as a sportswriter in New York, sat alone in his favorite bar, glumly contemplating a cup of tea. In Detroit that night, federal officers shut down two illegal stills (an act that would become common in the years ahead) and reported that their operators had offered bribes (which would become even more common). On the Maine-Canada border, reported a New Brunswick paper, “Canadian liquor in quantities from one gallon to a truckload is being hidden in the northern woods and distributed by automobile, sled and iceboat, on snowshoes and skis.”

The crusaders who had struggled for decades to place Prohibition in the Constitution celebrated with rallies, prayer sessions and ritual interments of effigies representing John Barleycorn, the symbol of alcohol’s evils. “Men will walk upright now, women will smile and the children will laugh,” the evangelist Billy Sunday told the 10,000 people who gathered at his tabernacle in Norfolk, Virginia. “Hell will be forever for rent.”

But Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane may have provided the most accurate view of the United States of America on the edge of this new epoch 90 years ago. “The whole world is skew-jee, awry, distorted and altogether perverse,” Lane wrote in a letter on January 19. “...All goes merry as a dance in hell.”

How did it happen? How did a freedom-loving people decide to give up a private right that had been freely exercised by millions since the first European colonists arrived in the New World? How did they condemn to extinction what was, at the very moment of its death, the fifth-largest industry in the nation? How did they append to their most sacred document 112 words that knew only one precedent in American history? With that single previous exception, the original Constitution and its first 17 amendments concerned the activities of government, not of citizens. Now there were two exceptions: you couldn’t own slaves, and you couldn’t buy alcohol.

But in its scope, Prohibition was much, much more complicated than that, initiating a series of innovations and alterations revolutionary in their impact. The men and women of the temperance movement created a template for political activism that is still followed a century later. They also abetted the creation of a radical new system of federal taxation, lashed their domestic goals to the conduct of World War I and carried female suffrage to the brink of passage.

And the 18th Amendment, ostensibly addressing the single subject of intoxicating beverages, would set off an avalanche of change in areas as diverse as international trade, speedboat design, tourism practices and the English language. It would provoke the establishment of the first nationwide criminal syndicate, the idea of home dinner parties, the deep engagement of women in political issues other than suffrage and the creation of Las Vegas.

Prohibition fundamentally changed the way we live. How the hell did that happen?

It happened, to a large degree, because Wayne Wheeler made it happen.

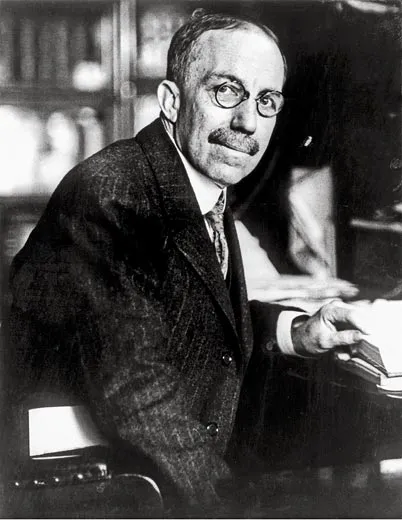

How does one begin to describe the impact of Wayne Bidwell Wheeler? You could do worse than to begin at the end, with the obituaries that followed his death, at 57, in 1927—obituaries, in the case of those quoted here, from newspapers that by and large disagreed with everything he stood for. The New York Herald Tribune: “Without Wayne B. Wheeler’s generalship it is more than likely we should never have had the Eighteenth Amendment.” The Milwaukee Journal: “Wayne Wheeler’s conquest is the most notable thing of our times.” The Baltimore Evening Sun had it absolutely right and at the same time completely wrong: “Nothing is more certain than that when the next history of this age is examined by dispassionate men, Wheeler will be considered one of its most extraordinary figures.” No one remembers, but he was.

Wheeler was a small man, 5-foot-6 or 7. Wire-rimmed glasses, a tidy mustache, eyes that crinkled at the corners when he ventured one of the tight little smiles that were his usual reaction to the obloquy of his opponents—even at the peak of his power in the 1920s, he looked more like a clerk in an insurance office than a man who, in the description of the militantly wet Cincinnati Enquirer, “made great men his puppets.” On his slight frame he wore a suit, a waistcoat and, his followers believed, the fate of the Republic.

Born on a farm near Youngstown, Ohio, in 1869, he was effectively born anew in 1893, when he found himself in a Congregational church in Oberlin, Ohio, listening to a temperance lecture delivered by the Rev. Howard Hyde Russell, a former lawyer who had recently founded an organization called the Anti-Saloon League (ASL). Wheeler had put himself through Oberlin College by working as a waiter, janitor, teacher and salesman. Now, after joining Russell in prayer, he signed on as one of the first full-time employees of the ASL, which he would turn into the most effective political pressure group the country had yet known.

It was, in fact, Wheeler who coined the term “pressure group.” When he teamed up with Russell in 1893, the temperance movement that had begun to manifest itself in the 1820s had hundreds of thousands of adherents but diffuse and ineffectual leadership. The most visible anti-alcohol leader, Frances Willard of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), had diluted her organization’s message by embracing a score of other issues, ranging from government ownership of utilities to vegetarianism. The nascent Prohibition Party had added forest conservation and post office policy to its anti-liquor platform. But Russell, with Wheeler by his side, declared the ASL interested in one thing only: the abolition of alcohol from American life.

Their initial objective was a law in every state banning its manufacture and sale. Their tactics were focused. A politician who supported anti-liquor laws could count on the league’s support, and a politician who did not could count on its ferocious opposition. “The Anti-Saloon League,” Russell said, “is formed for the purpose of administering political retribution.”

Wheeler became its avenging angel. Years later he said he joined the ASL because he was inspired by the organization’s altruism and idealism. But despite all the tender virtues he may have possessed, none was as essential as a different quality, best summarized by a classmate’s description: Wayne Wheeler was a “locomotive in trousers.” While clerking for a Cleveland lawyer and attending classes at Western Reserve Law School, Wheeler worked full time for the league, riding his bicycle from town to town to speak to more churches, recruit more supporters. After he earned his law degree in 1898 and took over the Ohio ASL’s legal office, his productivity only accelerated. He initiated so many legal cases on the league’s behalf, delivered so many speeches, launched so many telegram campaigns and organized so many demonstrations (“petitions in boots,” he called them) that his boss lamented that “there was not enough Mr. Wheeler to go around.”

Soon Wheeler and the ASL had effective control of the Ohio legislature. They had opposed 70 sitting legislators of both parties (nearly half the entire legislative membership) and defeated every one of them. Now the state could pass a law that had long been the league’s primary goal: a local-option bill that would put power over the saloon directly in voters’ hands. If Cincinnatians voted wet, Cincinnati would be wet; if Daytonites voted dry, they would be dry.

After different versions of the measure had passed both houses of the legislature, Gov. Myron T. Herrick persuaded members of the conference committee to adopt some modifications he deemed necessary to make the law workable and equitable. To the league, this was heresy. After Herrick signed the amended bill into law in the election year of 1905, Wheeler, playing for stakes greater than the ASL had ever risked before, took him on directly.

The governor was no easy target. A lawyer and banker from Cleveland, he was the political creation of Senator Mark Hanna, the Republican Boss of Bosses. In 1903, Herrick had been elected governor with the largest plurality in Ohio history; for the 1905 campaign, he had substantial campaign funds, as well as the goodwill of many a churchgoer for having vetoed a bill that would have legalized racetrack betting. And Ohio Republicans had lost only one gubernatorial election in almost two decades.

Wheeler and the ASL sponsored more than 300 anti-Herrick rallies throughout the state and mobilized their supporters in the churches by suggesting that the governor—“the champion of the murder mills”—was a pawn of the liquor interests. When the Brewers’ Association sent out a confidential letter urging its members to lend quiet but material support to Herrick (his Democratic opponent was a vocal temperance advocate), Wheeler said he “got [a copy of the letter] on Thursday before election, photographed it and sent out thousands of them to churches on Sunday.” In a race that drew what was at the time the largest turnout for an Ohio gubernatorial election, every other Republican on the statewide ticket was elected, but Myron Herrick’s political career was over.

“Never again,” Wheeler boasted, “will any political party ignore the protests of the church and the moral forces of the state.” Nor, in a word, would they ignore Wayne B. Wheeler.

The ASL’s state-by-state campaign was reasonably effective, particularly in the South. But in 1913, two events led the organization to adopt a new strategy. First, Congress overrode President William Howard Taft’s veto of something called the Webb-Kenyon Act, which outlawed the importation of alcoholic beverages into a dry state. The stunning 246 to 95 override vote in the House of Representatives showed not just the power of the anti-liquor forces but also how broadly representative they had become.

The override was followed by enactment of a national income tax authorized by the recently ratified 16th Amendment. Until 1913, the federal government had depended on liquor taxes for as much as 40 percent of its annual revenue. “The chief cry against national Prohibition,” the ASL’s executive committee said in a policy statement that April, “has been that the government must have the revenue.” But with an income tax replacing the levy on liquor, that argument evaporated, and the ASL could move beyond its piecemeal approach and declare its new goal: “National Prohibition, [to] be secured through the adoption of a Constitutional Amendment.”

The ASL statement called this new policy “The Next and Final Step.” But the league could not take that step without extracting Wheeler from Ohio and sending him to Washington. Although that didn’t happen officially until 1916, Wheeler’s domination of the highest councils of the ASL began with the 1913 decision to push for a Prohibition amendment. Shuttling between Columbus and the ASL’s Washington office, he displayed the strategic savvy and the unstoppable drive that would eventually lead the editors of the New York Evening World to proclaim him “the legislative bully before whom the Senate of the United States sits up and begs.”

By the time Wheeler stepped onto the national stage, he had long since mastered his legislative parlor tricks. When Lincoln Steffens had visited Columbus several years earlier, Wheeler explained his tactics to the great muckraker. “I do it the way the bosses do it, with minorities,” Wheeler said. By delivering his voters to one candidate or another in a close race, he could control an election: “We’ll vote against all the men in office who won’t support our bills. We’ll vote for candidates who will promise to.” Wheeler, who had greeted Steffens amiably—“as a fellow reformer,” Steffens recalled— now “hissed his shrewd, mad answer” to those politicians who would betray ASL voters: “We are teaching these crooks that breaking their promises to us is surer of punishment than going back on their bosses, and some day they will learn that all over the United States—and we’ll have national Prohibition.”

A constitutional amendment mandating such a thing required a two-thirds majority in each house of Congress as well as legislative majorities in 36 states. Wheeler’s skill at achieving majorities by manipulating minorities freed the ASL from the more cumbersome referendum and initiative movement. When voters were offered a simple yes-or-no, dry-or-wet choice on a ballot measure, a minority was only a minority. But when two candidates in an election could be differentiated by isolating one issue among many, Wheeler’s minority could carry the day. A candidate with, say, the support of 45 percent of the electorate could win with the added votes of the ASL bloc. In other words, in legislative elections, the power of Wheeler’s minority could be measured in multiples.

A resolution calling for a Prohibition amendment had been introduced in nearly every Congress since 1876, but none had ever emerged from committee. And no version of a female suffrage amendment had gotten as far as floor debate in two decades. But in the congressional session of 1914, both were reported out of committee on the same day.

This was no coincidence. The suffrage movement had long shared a constituency with the anti-liquor movement. Frances Willard and the WCTU campaigned actively for both causes. Susan B. Anthony had first become involved in securing the vote for women when she was denied the right to speak at a temperance convention in 1852 in Albany, New York. By 1899, after half a century of suffrage agitation, Anthony attempted to weld her movement to the Prohibition drive. “The only hope of the Anti-Saloon League’s success,” she told an ASL official, “lies in putting the ballot into the hands of women.” In 1911, Howard Russell’s successor as the league’s nominal leader, Purley A. Baker, agreed. Women’s suffrage, he declared, was “the antidote” to the efforts of the beer and liquor interests.

This was not the only alliance that the ASL made with other movements. Though in its public campaigns it stuck to its single issue, the league had worked with Western populists to secure ratification of the income tax amendment. It made common cause with progressives who were fighting the political power of the saloons in order to bring about the “uplift” of urban immigrants. In the South, Prohibitionists stood side by side with racists whose living nightmare was the image of a black man with a bottle in one hand and a ballot in the other.

Such alliances enabled the dry forces to make their first congressional impact on December 22, 1914, when a version of a Prohibition amendment came up for a vote before the entire House of Representatives. The final tally was 197 for, 190 against—not the two-thirds majority the Constitution required, but an astonishing victory, nonetheless. Dry votes came from both parties and from every part of the country. Nearly two-thirds of the affirmative voters lived in towns with fewer than 10,000 people, but among the House members of the largely urban Progressive Party, 17 of the 18 who voted went dry.

The ASL’s assiduous attention to Congress had made wet politicians wobble, uncertain politicians sprint for dry shelter and dry politicians flex their biceps. Heading toward the 1916 elections, the league’s political expenditures exceeded the 2010 equivalent of $50 million in a single year.

By Election Day, the ASL’s leadership, its publicists and its 50,000 lecturers, fund-raisers and vote counters had completed their work. While the rest of the nation remained in suspense as the votes in the 1916 presidential balloting were counted in California—the state’s 13 electoral votes would re-elect Woodrow Wilson—the managers of the ASL slept comfortably.

“We knew late election night that we had won,” Wheeler would recall a decade later. The league, he wrote, had “laid down such a barrage as candidates for Congress had never seen before.” Every wet measure on every statewide ballot was defeated. Four more states had voted themselves dry, including Michigan, the first Northern industrial state to make the leap. Some form of dry law was now on the books in 23 states. And, wrote Wheeler, “We knew that the Prohibition amendment would be submitted to the States by the Congress just elected.”

Shortly after that Congress was sworn in, Senator Morris Sheppard of Texas introduced the resolution that would become the 18th Amendment. Sheppard was a Yale man, a Shakespeare scholar and one of the Senate’s leading progressive figures. But all that mattered to Wheeler was that Sheppard also believed that the liquor sellers preyed most dangerously on the poor and uneducated.

In fact, Wheeler’s devotion to the dream of a dry America accommodated any number of unlikely allies. Billy Sunday, meet pioneering social worker Jane Addams: you’re working together now. The evangelical clergy of the age were motivated to support Prohibition because of their faith; reformers like Addams signed on because of the devastating effect that drunkenness had on the urban poor. Ku Klux Klan, shake hands with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW): you’re on the same team. The Klan’s anti-liquor sentiment was rooted in its hatred of the immigrant masses in liquor-soaked cities; the IWW believed that liquor was a capitalist weapon used to keep the working classes in a stupor.

After the Sheppard amendment passed both houses of Congress with gigantic majorities in late 1917, Wheeler turned to what most political figures believed to be a much tougher battle, a state-by-state ratification campaign. The drys would need to win over both legislative houses in at least 36 states to reach the three-quarters requirement.

To the shock of many, ratification would come with astonishing velocity. For years the ASL’s vast national organization had been mobilizing its critical minority of voters to carry legislative elections in every state. But what really put across ratification in an eventual 46 states (Connecticut and Rhode Island were the only holdouts) had nothing to do with political organizing. The income tax had made a Prohibition amendment fiscally feasible. The social revolution wrought by the suffragists had made it politically plausible. Now Wheeler picked up the final tool he needed to wedge the amendment into the Constitution: a war.

A dry Wisconsin politician named John Strange summarized how the ASL was able to use World War I to attain its final goal: “We have German enemies across the water,” Strange said. “We have German enemies in this country, too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz and Miller.” That was nothing compared with the anti-German—and pro-Prohibition—feeling that emerged from a Senate investigation of the National German-American Alliance (NGAA), a civic group that during the 1910s had spent much of its energy opposing Prohibition.

The Senate hearings were a disaster for wets. At a time when most Amerians reviled all things German—when the governor of Iowa declared that speaking German in public was unlawful, and playing Beethoven was banned in Boston, and sauerkraut became known as “liberty cabbage”—the NGAA was an easy target. When the hearings revealed that NGAA funds came largely from the beer barons, and that beer money had secretly secured the purchase of major newspapers in several cities, ratification proceeded, said the New York Tribune, “as if a sailing-ship on a windless ocean were sweeping ahead, propelled by some invisible force.”

“Invisible” was how Wayne Wheeler liked it. In fact, he had personally instigated, planned and materially abetted the Senate inquiry—inquisition, really—into the NGAA. “We are not willing it be known at present that we started the investigation,” Wheeler told a colleague. But he added, “You have doubtless seen the way the newspapers have taken up the German-American Alliance. They are giving it almost as much attention as the Acts of Congress itself.”

The Senate hearings had begun on September 27, 1918. Less than four months later, Nebraska ratified (by a 96 to 0 vote in its lower house), and the 18th Amendment was embedded in the Constitution. From the moment of submission, it had taken 394 days to meet the approval of 36 state legislatures—less than half as long as it had taken 11 of the first 14 states to approve the Bill of Rights.

Not seven years after Prohibition took effect, on January 17, 1920 (the amendment had stipulated it would go into effect one year after ratification), Wayne B. Wheeler died. He had taken a rare vacation on Lake Michigan when his wife was killed in a freak fire and his father-in-law thereupon was felled by a heart attack. Wheeler had been in ill health for months; the vacation that he had hoped would restore him instead led to his own death by heart failure just three weeks after the fire.

Until virtually the end, Wheeler remained as effective as he had been in the years leading up to the passage of the 18th Amendment. He was intimately involved in the drafting of the Volstead Act, which specified the means of enforcing the Prohibition amendment. All subsequent legislation refining the liquor-control laws required his imprimatur. He still determined whether candidates for Congress would receive the ASL’s endorsement. And he underscored his authority by supervising a gigantic patronage operation, controlling appointments to the Prohibition Bureau, which was set up to police the illegal liquor trade.

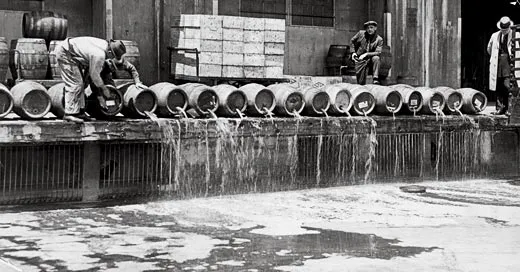

But for all his political might, Wheeler could not do what he and all the other Prohibitionists had set out to do: they could not purge alcoholic beverages from American life. Drinking did decline at first, but a combination of legal loopholes, personal tastes and political expediency conspired against a dry regime.

As declarative as the 18th Amendment was—forbidding “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors”—the Volstead Act allowed exceptions. You were allowed to keep (and drink) liquor you had in your possession as of January 16, 1920; this enabled the Yale Club in New York, for instance, to stockpile a supply large enough to last the full 14 years that Prohibition was in force. Farmers and others were allowed to “preserve” their fruit through fermentation, which placed hard cider in cupboards across the countryside and homemade wine in urban basements. “Medicinal liquor” was still allowed, enriching physicians (who generally charged by the prescription) and pharmacists (who sold such “medicinal” brands as Old Grand-Dad and Johnnie Walker). A religious exception created a boom in sacramental wines, leading one California vintner to sell communion wine—legally—in 14 different varieties, including port, sherry, tokay and cabernet sauvignon.

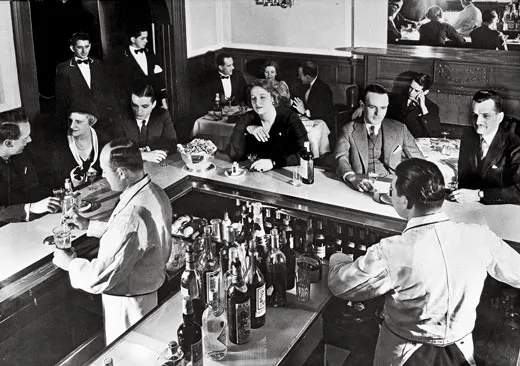

By the mid-’20s, those with a taste for alcohol had no trouble finding it, especially in the cities of the East and West coasts and along the Canadian border. At one point the New York police commissioner estimated there were 32,000 illegal establishments selling liquor in his city. In Detroit, a newsman said, “It was absolutely impossible to get a drink...unless you walked at least ten feet and told the busy bartender what you wanted in a voice loud enough for him to hear you above the uproar.” Washington’s best-known bootlegger, George L. Cassiday (known to most people as “the man in the green hat”), insisted that “a majority of both houses” of Congress bought from him, and few thought he was bragging.

Worst of all, the nation’s vast thirst gave rise to a new phenomenon—organized crime, in the form of transnational syndicates that controlled everything from manufacture to pricing to distribution. A corrupt and underfunded Prohibition Bureau couldn’t begin to stop the spread of the syndicates, which considered the politicians who kept Prohibition in place their greatest allies. Not only did Prohibition create their market, it enhanced their profit margins: from all the billions of gallons of liquor that changed hands illegally during Prohibition, the bootleggers did not pay, nor did the government collect, a single penny of tax.

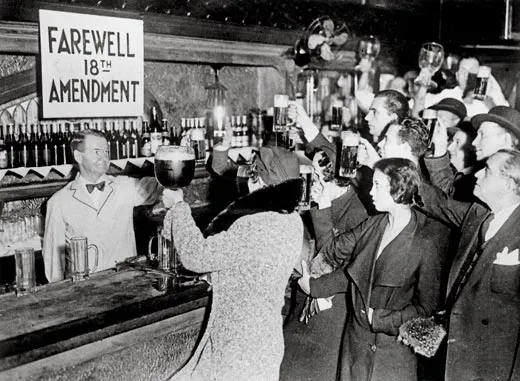

In fact, just as tax policy, in the form of the income tax amendment, had paved the way for Prohibition, so did it shape Prohibition’s eventual death. Rampant criminality, epidemic disrespect for law and simple exhaustion had turned much of the country against the 18th Amendment by the late ’20s, but the arrival of the Great Depression sealed the deal. As income tax revenues plummeted along with incomes, the government was running on empty. With the return of beer alone, Franklin Roosevelt said during his 1932 campaign, the federal treasury would be enriched by hundreds of millions of dollars.

On December 5, 1933, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the 21st Amendment and Prohibition came to an inglorious end. That was a little more than six years after the death of the man who had brought it to life. In a posthumous biography written by a former colleague, Wayne B. Wheeler was described as a man who “controlled six Congresses, dictated to two Presidents...directed legislation...for the more important elective state and federal offices, held the balance of power in both Republican and Democratic parties, distributed more patronage than any dozen other men, supervised a federal bureau from outside without official authority, and was recognized by friend and foe alike as the most masterful and powerful single individual in the United States.”

And then, almost immediately, he was forgotten.

Copyright © 2010 by Last Laugh, Inc. From the forthcoming book Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition, by Daniel Okrent, to be published by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.