What (or Who) Caused the Great Chicago Fire?

The true story behind the myth of Mrs. O’Leary and her cow

![]()

Late one night, when we were all in bed,

Mrs. O’Leary lit a lantern in the shed.

Her cow kicked it over, then winked her eye and said,

“There’ll be a hot time in the old town tonight!”

— Chicago folksong

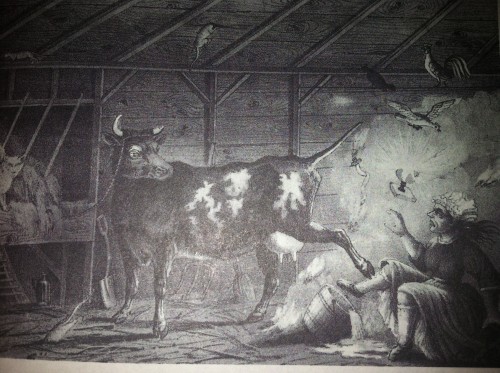

An unflattering depiction of Catherine O’Leary inside her infamous barn. From “The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow.”

There is no known photograph of Catherine O’Leary, and who could blame her for shunning the cameras? After those two catastrophic days in October 1871, when more than 2,000 acres of Chicago burned, reporters continually appeared on Mrs. O’Leary’s doorstep, calling her “shiftless and worthless” and a “drunken old hag with dirty hands.” Her husband sicced dogs at their ankles and hurled bricks at their heads. P.T. Barnum came knocking to ask her to tour with his circus; she reportedly chased him away with a broomstick. Her dubious role in one of the greatest disasters in American history brought her fame she never wanted and couldn’t deflect. When she died 24 years later of acute pneumonia, neighbors insisted the true cause was a broken heart.

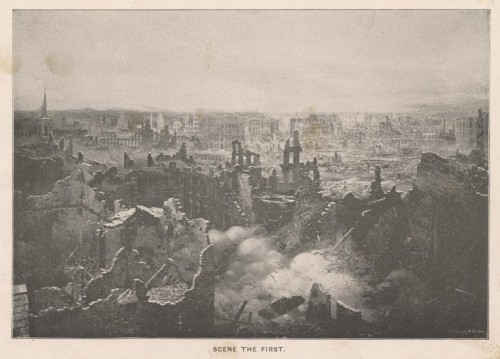

Mrs. O’Leary claimed to be asleep on the night of Sunday, October 8, when flames first sparked in the barn next to the family cottage on DeKoven Street. The blaze traveled in northeast, tearing through shanties and sheds and leaping across Taylor Street, the heat so fierce that fireman Charles Anderson could hold his hose to the flames only when shielded by a door. His hat curdled on his head. All spare engines were called to the growing conflagration, prompting one fire marshal to ask another: “Where has this fire gone to?” The answer was swift and apt: “She has gone to hell and gone.” Residents noticed that a freakish wind whipped the flames into great walls of fire more than 100 feet high, a meteorological phenomenon called “convection whirls”—masses of overheated air rising from the flames and began spinning violently upon contact with cooler surrounding air. “The wind, blowing like a hurricane, howling like myriads of evil spirits,” one witness later wrote, “drove the flames before it with a force and fierceness which could never be described or imagined.”

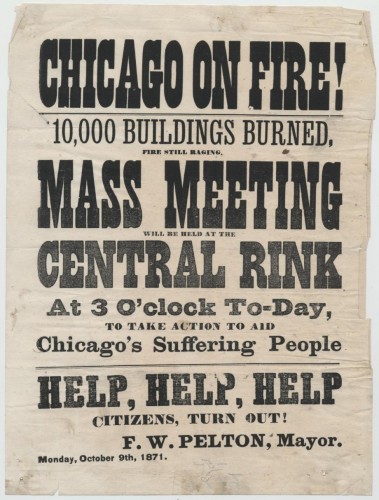

Although the wind never exceeded 30 miles per hour, these “fire devils,” as they were dubbed, pushed the flames forward and across the city. By early morning on Tuesday, October 10, when rain extinguished the last meekly glowing ember, the city was ravaged: $200 million worth of property destroyed, 300 lives lost and 100,000 people—one third of the city’s population—left homeless. The Chicago Tribune likened the damage to that in Moscow after Napoleon’s siege in 1812. In a peculiar twist of fate, and one that would not go unnoticed by the city’s press, the fire spared the O’Leary family’s home.

Before the Great Chicago Fire, no one took notice of Patrick and Catherine O’Leary, two Irish immigrants who lived with their five children on the city’s West Side. Patrick was a laborer and Catherine sold milk from door to door, keeping her five cows in the barn. Even before the fire died out on the city’s northern edges, the Chicago Evening Journal implicated her, reporting that it began “on the corner of DeKoven and Twelfth Streets, at about 9 o’clock on Sunday evening, being caused by a cow kicking over a lamp in a stable in which a woman was milking”—a scenario that originated with children in the neighborhood. Similar articles followed, many perpetuating ethnic stereotypes and underscoring nativist fears about the city’s growing immigrant population. The Chicago Times, for one, depicted the 44-year-old Catherine as “an old Irish woman” who was “bent almost double with the weight of many years of toil, trouble and privation” and concluded that she deliberately set fire to her barn out of bitterness: “The old hag swore she would be revenged on a city that would deny her a bit of wood or a pound of bacon.”

During an inquiry held by the Board of Police and Fire Commissioners to determine the cause of the blaze, Catherine testified that she went to bed sometime between eight o’clock and eight-thirty, and was sleeping when her husband roused her with the words, “Cate, the barn is afire!” She ran outside to see it for herself, and watched as dozens of neighbors worked to save adjacent homes, fixing two washtubs to fire hydrants and running back and forth with buckets of water. One of them had thrown a party that night—Catherine recalled hearing fiddle music as she prepared for bed—and a woman named Mrs. White told her that someone had wandered away from the gathering and slipped into her barn. “She mentioned a man was in my barn milking my cows,” Catherine said. “I could not tell, for I didn’t see it.”

The board also questioned a suspect named Daniel Sullivan, who lived directly across from the O’Leary’s on DeKoven Street, and who had first alerted Patrick O’Leary to the fire. Sullivan, known as “Peg Leg” for his wooden limb, said he had attended the party and left about half past nine. As he stepped out into the night, he said, he saw a fire in the O’Learys’ barn. He ran across the street hollering, “Fire, fire, fire!” and headed straight to the source of the flames, reasoning that he might be able to save the cows. “I knew a horse could not be got out of a fire unless he be blinded,” Sullivan testified, “but I didn’t know but cows could. I turned to the left-hand side. I knew there was four cows tied to that end. I made at the cows and loosened them as quick as I could. I got two of them loose, but the place was too hot. I had to run when I saw the cows were not getting out.”

After nine days of questioning 50 people—testimony that made up more than 1,100 handwritten pages—the board members issued an inconclusive report about the fire’s cause. “Whether it originated from a spark blown from a chimney on that windy night,” it read, “or was set on fire by human agency, we are unable to determine.” Nevertheless Catherine O’Leary remained culpable in the public’s eye. None of her contemporaries bothered to ask the obvious questions that indicate her innocence: Why would she leave the barn after setting the fire—even accidentally—and go back into her home? Why would she not scream for help? Why would she risk losing her cows, her barn, and possibly her home without trying to save them?

One of Catherine’s sons, James, was two years old at the time of the fire, and would grow up to become “Big Jim” O’Leary, notorious saloon proprietor and gambling kingpin. Over the years he granted numerous newspaper interviews, complaining that, “That musty old fake about the cow kicking over the lamp gets me hot under the collar.” He insisted that the fire was caused by the spontaneous combustion of “green” (or newly harvested) hay, large quantities of which had been delivered to the barn on the eve of the fire. But the summer of 1871 had been one long and merciless heat wave in Chicago, with scorching temperatures extending into the fall, making it likely that the hay was thoroughly dry before being stored in the barn.

Patrick and Catherine O’Leary sold their cottage on DeKoven Street in 1879 and moved many times, eventually settling in on South Halstead Street on what was then the far South Side. In 1894, the year before Catherine died, her physician did what she’d always refused to do and gave a comment to the press:

“It would be impossible for me to describe to you the grief and indignation with which Mrs. O’Leary views the place that has been assigned her in history. That she is regarded as the cause, even accidentally, of the Great Chicago Fire is the grief of her life. She is shocked at the levity with which the subject is treated and at the satirical use of her name in connection with it…. She admits no reporters to her presence, and she is determined that whatever ridicule history may heap on her it will have to do it without the aid of her likeness. Many are the devices that have been tried to procure a picture of her, but she has been too sharp for any of them. No cartoon will ever make any sport of her features. She has not a likeness in the world and will never have one.”

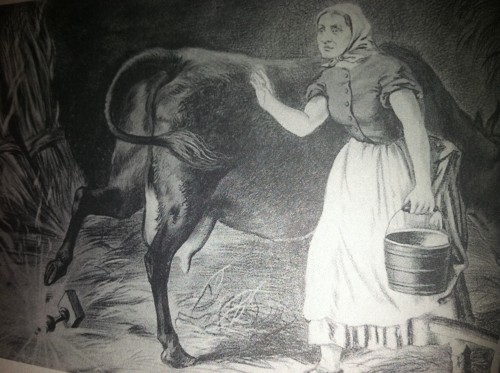

A sympathetic depiction of Catherine O’Leary. From “The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow.”

Patrick and Catherine O’Leary are buried in Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery in Chicago, next to their son James and his wife. In 1997, the Chicago City Council passed a resolution exonerating Catherine—and her cow—from all blame.

Sources:

Books:

Richard F. Bales, The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O’Leary’s Cow. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2002; Owen J. Hurd, After the Fact: The Surprising Fates of American History’s Heroes, Villains, and Supporting Characters. New York: Penguin Group, 2012; Carl Smith, Urban Disorder and the Shape of Belief. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Articles:

“Fire and Death in Chicago.” New York Herald, October 10, 1871; “The Chicago Fire: Vivid Accounts by Eyewitnesses.” Cincinnati Daily Gazette, October, 11, 1871; “The Chicago Fire! The Flames Checked At Last.” Richmond Whig, October 13, 1871; “The Great Fire That Wiped Out Chicago.” Chicago Inter-Ocean, October 9, 1892; “Lesson of the O’Leary Cow.” Biloxi Daily Herald, July 5, 1899; “Mrs. O’Leary Is Dead.” Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1895; “O’Leary Defends His Mother’s Cow.” Trenton Evening Times, December 1, 1909; “Alderman Tries to Exonerate Mrs. O’Leary and Her Cow.” Rockford (IL) Register Star, September 12, 1997.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/karen.png)