What the Newspapers Said When Lincoln Was Killed

The initial reaction to the president’s death was a wild mixture of grief, exultation, vengefulness and fear

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/1a/9a1afeeb-8b8f-4cd7-941c-c5ededc6bcea/mar2015_m02_lincolnreputation-cr.jpg)

Even as he hid out in Zekiah Swamp in Southern Maryland, John Wilkes Booth—famished, soaked, shivering, in agony from his fractured fibula and feeling “hunted like a dog”—clung to the belief that his oppressed countrymen had “prayed” for President Abraham Lincoln’s “end.” Surely he would be vindicated when the newspapers printed his letter.

“Many, I know—the vulgar herd—will blame me for what I am about to do, but posterity, I am sure, will justify me,” he had boasted on April 14, 1865, the morning he determined to kill the president, in a letter to Washington’s National Intelligencer. Lincoln had famously loved Shakespeare, and Booth, the Shakespearean actor, considered the president a tyrant and himself the Bard’s most infamous avenger reborn. “It was the spirit and ambition of Caesar that Brutus struck at,” he boasted. “‘Caesar must bleed for it.’”

As he waited to cross the Potomac River into Virginia, Booth finally glimpsed some recent newspapers for the first time since he had fled Ford’s Theatre. To his horror, they described him not as a hero but as a savage who had slain a beloved leader at the peak of his fame. “I am here in despair,” he confided to his pocket diary on April 21 or 22. “And why? For doing what Brutus was honored for, what made [William] Tell a hero. And yet I for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew am looked upon as a common cutthroat.” Booth died clinging to the hope that he would be absolved—and lionized.

He had no way of knowing that the Intelligencer never received his letter. The fellow actor to whom Booth had entrusted it, fearful of being charged with complicity in the president’s murder, burned it. Not until years later, after he miraculously “reconstructed” all 11 paragraphs, would it appear in print. By then, Lincoln was almost universally embraced as a national icon—the great emancipator and the preserver of the Union, a martyr to freedom and nationalism alike. But that recognition did not arrive immediately, or everywhere; it took weeks of national mourning, and years of published reminiscences by his familiars, to burnish the legend. In shooting Lincoln on Good Friday, 1865, Booth intended to destabilize the United States government, but what he most destabilized was the psyche of the American people. Just the previous month they had heard the president plead for “malice toward none” in his Second Inaugural Address. Now, America’s first presidential assassination unleashed an emotional upheaval that conflated vengeance with sorrow.

Booth’s braggadocio seems delusional now, but it would have appeared less so at the time. Throughout his presidency—right up to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9—Lincoln had attracted no shortage of bitter enemies, even in the North. Just six months earlier, he had been viewed as a partisan mortal: a much-pilloried politician running in a typically divisive national canvass for a second term as president. “The doom of Lincoln and black republicanism is sealed,” railed one of Lincoln’s own hometown newspapers after he had been renominated in June 1864. “Corruption and the bayonet are impotent to save them,” the Democratic Illinois State Register added. Not even the shock of his assassination could persuade some Northern Democrats that he didn’t deserve a tyrant’s death.

“They’ve shot Abe Lincoln,” one jubilant Massachusetts Copperhead shouted to his horrified Yankee neighbors when he heard the news. “He’s dead and I’m glad he’s dead.” On the other extreme of the political spectrum, George W. Julian, a Republican congressman from Indiana, acknowledged that his fellow Radicals’ “hostility towards Lincoln’s policy of conciliation and contempt for his weakness were undisguised; and the universal feeling among radical men here is that his death is a god-send.”

Perhaps nothing more vividly symbolized the seismic impact of the assassination than the scene of utter confusion that unfolded minutes after Booth fired his single shot. It did not go unrecorded. An artist named Carl Bersch happened to be sitting on a porch nearby, sketching a group of Union soldiers and musicians in an exuberant victory procession up Tenth Street in front of Ford’s Theatre. Suddenly Bersch noticed a commotion from the direction of the theater door.

As a “hushed committee” emerged and began bearing the president’s inert frame through the crowd of revelers toward William Petersen’s boardinghouse across the street, the martial music dissolved and the parade melted into disarray. Remarkably, Bersch kept his composure and incorporated what he called the “solemn and reverent cortege” into his sketch. Later, the artist expanded it into a painting he titled Lincoln Borne by Loving Hands. It is the only known visual record of an end-of-war celebration subdued by the news of Lincoln’s murder, and it seemed to parallel the pandemonium about to overtake the North. As Walt Whitman put it, “an atmosphere of shock and craze” quickly gripped the shattered country, one in which “crowds of people, fill’d with frenzy” seemed “ready to seize any outlet for it.”

For 12 chaotic days—even as hundreds of thousands of heartbroken admirers massed in Northern cities for elaborate funerals for the slain president—the assassin remained terrifyingly at large, with Federal forces in pursuit. Americans followed the story of the manhunt for John Wilkes Booth as avidly as the troops chased him.

In Washington, church bells resumed their recent pealing—but the rhythmic chiming that had rung so triumphant after Lee surrendered now seemed muffled. Victory celebrations were canceled, bonfires extinguished, fireworks and illuminations doused, rallies canceled. Instead, city after city adorned public buildings with so much thick black crape that recognizable architecture all but vanished beneath the bunting. Citizens took to wearing black-ribboned badges adorned with small photographs of the martyred president. A young New York City merchant named Abraham Abraham (long before he and a partner founded the retail empire Abraham & Straus) reverently placed a Lincoln bust in his shop window, one of many shopkeepers to make gestures to honor him. Not far from that storefront, self-described “factory boy” and future labor leader Samuel Gompers “cried and cried that day and for days I was so depressed I could scarcely force myself to work.”

Given the timing of the assassination, Easter and Passover services assumed profound new meaning. Christian ministers took to their pulpits on Easter Sunday, April 16, to liken the slain president to a second Jesus, who, like the first, died for his people’s sins and rose to immortality. During Passover observances, Jewish rabbis mourned the murdered leader as a born-again Moses who—as if echoing the words from Leviticus—had proclaimed liberty throughout the land and to all the inhabitants thereof. Yet, like the ancient lawgiver in the Book of Exodus, Lincoln had not lived to see the Promised Land himself.

Rabbi Henry Vidaver spoke for many Jewish prelates, Northern as well as Southern, when he told his St. Louis congregants that Lincoln’s death brought “woe and desolation into every heart and household throughout the whole Union” during holy days otherwise devoted to jubilee. In Lincoln’s hometown of Springfield, Illinois, Methodist Bishop Matthew Simpson tried to console the slain president’s neighbors by assuring them that Lincoln had been “by the hand of God singled out to guide our Government in these troublous times.” Aware that many Northerners felt vengeful toward his killer, Simpson quoted Lincoln’s recent injunction against malice.

Still, the desire for reprisal could not be entirely checked. Embittered Washingtonians subjected “any man showing the least disrespect to the memory of the universally lamented dead” to “rough treatment,” the New York Times reported. The Union Army—whose soldiers had voted for Lincoln in huge majorities the previous November—was harsh on dissidents. When a soldier named James Walker of the 8th California Infantry declared that Lincoln was a “Yankee son of a bitch” who “ought to have been killed long ago,” he was court-martialed and sentenced to death by firing squad. (An appeals court later commuted the sentence.) In all, military officials dishonorably discharged dozens of loose-lipped enlisted men like the Michigan soldier who dared to blurt out, in Lincoln’s hometown, “The man who killed Lincoln did a good thing.”

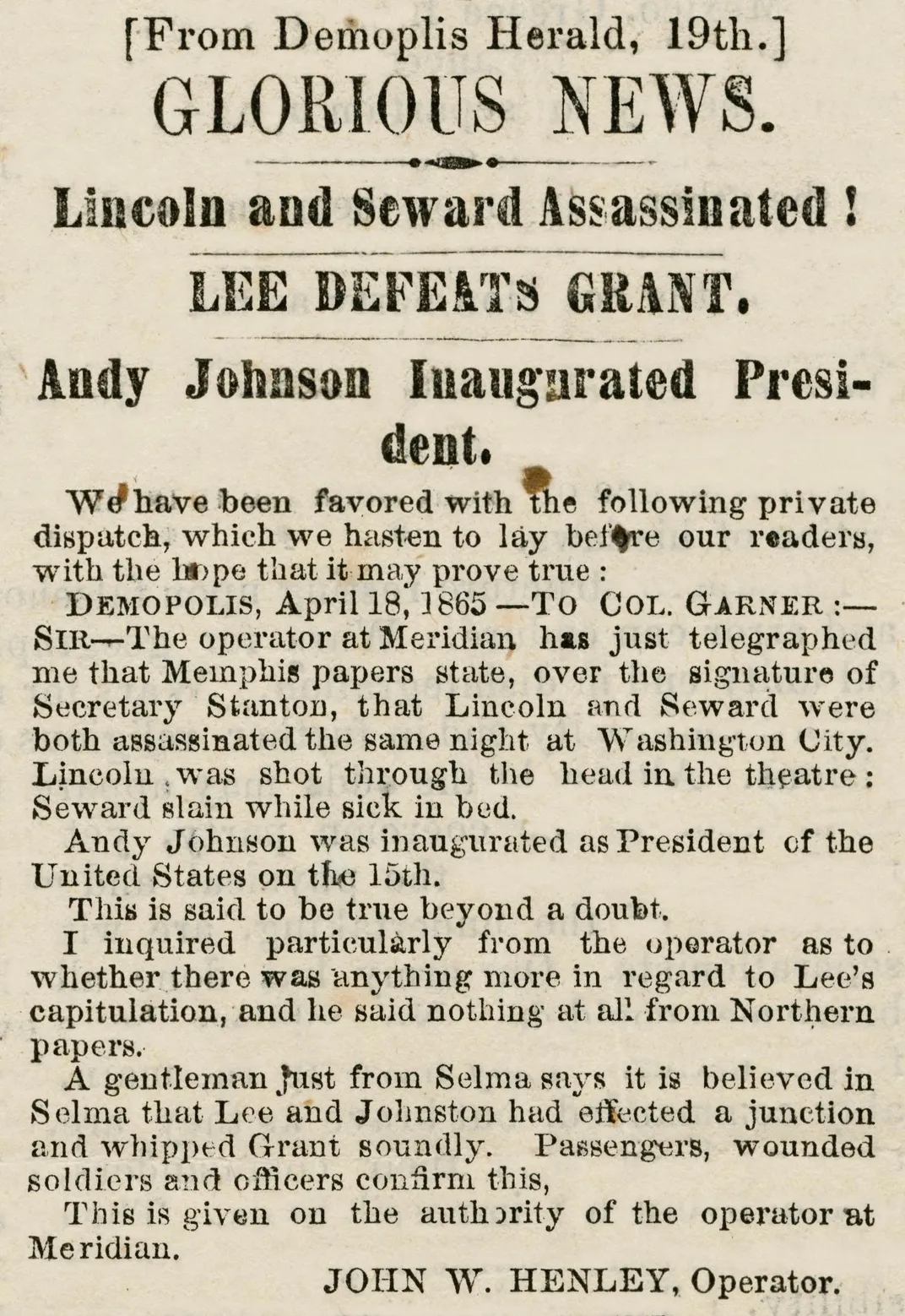

In the Upper South, many newspapers expressed shock and sympathy over Lincoln’s murder, with the Raleigh Standard conveying its “profound grief” and the Richmond Whig characterizing the assassination as the “heaviest blow which has fallen on the people of the south.” But not all Southern journals proffered condolences. The aptly named Chattanooga Daily Rebel opined: “Abe has gone to answer before the bar of God for the innocent blood which he has permitted to be shed, and his efforts to enslave a free people.” Thundering its belief that Lincoln had “sowed the wind and has reaped the whirlwind,” the Galveston News sneered: “In the plentitude of his power and arrogance he was struck down, and is so ushered into eternity, with innumerable crimes and sins to answer for.”

Many Southerners who reviled the Northern president held their tongues—because they feared they would be blamed for his murder. “A kind of horror seized my husband when he realised the truth of the reports that reached us of this tragedy,” recalled the wife of Clement C. Clay, who represented Alabama in the Confederate States Senate and, late in the war, directed Rebel secret agents from a posting in Canada. “God help us,” Senator Clay exclaimed. “I[t] is the worst blow that yet has been struck at the South.” Not long afterward, Union officials arrested Clay on suspicions that he had conspired in Lincoln’s assassination and threw him into prison for more than a year.

On the run in a doomed effort to keep the Lost Cause alive, Confederate President Jefferson Davis received word of the president’s death in an April 19 telegram that reached him in Charlotte, North Carolina. Demonstrating that, like his Northern counterpart, he knew his Shakespeare, Davis was reported by a witness to have paraphrased Lincoln’s favorite play, Macbeth: “If it were to be done, it were better it were well done,” adding, “I fear it will be disastrous for our people.” Later, in his postwar memoirs, Davis claimed that while others in his government-in-exile had “cheered” the news, he had expressed no “exultation” himself. “For an enemy so relentless in the war for our subjugation, we could not be expected to mourn,” he conceded with restrained candor, “yet, in view of its political consequences, it could not be regarded otherwise than as a great misfortune for the South.” The Union Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, ordered that Davis, like Clay, be indicted on charges that he conspired with Booth in Lincoln’s murder. (Davis, Clay and other Confederate leaders ultimately received amnesty from President Andrew Johnson.)

Some anti-Lincoln men did little to disguise their jubilation. A pro-Confederate minister in Canada was heard declaring “publicly at the breakfast table...that Lincoln had only gone to hell a little before his time.” More circumspect Confederate loyalists confided their satisfaction only to their securely locked personal journals. Though she decried violence in any form, Louisiana diarist Sarah Morgan judged the murdered Union president harshly: “[T]he man who was progressing to murder countless human beings,” Morgan wrote, “is interrupted in his work by the shot of an assassin.” From South Carolina, the most acclaimed Southern diarist of them all, Mary Boykin Chesnut, was succinct: “The death of Lincoln—I call that a warning to tyrants. He will not be the last president put to death in the capital, though he is the first.”

Even as such comments were being furtively recorded, Lincoln’s remains were being embalmed to the point of petrification so they could be displayed at public funerals in Washington, Baltimore, Harrisburg, Philadelphia, New York, Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Columbus, Indianapolis, Michigan City, Chicago and, finally, beneath signs reading “HOME IS THE MARTYR,” in Springfield.

No venue wore its dramatically changed emotions—and politics—more gaudily than Baltimore. As president-elect in 1861, Lincoln had felt compelled to pass through the so-called “Mob City” at night, in secret, and, some foes mocked, in disguise to evade a credible pre-inaugural assassination threat. In Lincoln’s atypically bitter recollection (which he chose not to make public), “not one hand reached forth to greet me, not one voice broke the stillness to cheer me.” Now, on April 21, 1865, in a scene suggesting a mass quest for atonement, tens of thousands of Baltimore mourners braved a pounding rain to pay their respects at Lincoln’s catafalque. Disappointed admirers at the back of the lines never got to glimpse the open coffin, which was punctually shut and carted away so the president’s remains could arrive at their next stop in time.

Similar scenes of mass grief played out repeatedly as Lincoln’s body headed north, then west, to its final resting place. New York—the scene of vicious, racially animated draft riots in 1863—hosted the grandest funeral of all. More than 100,000 New Yorkers waited patiently to gaze briefly at Lincoln’s remains as they lay in state at City Hall (a scene sketched by Currier & Ives artists and immortalized in a single photograph, which Stanton inexplicably ordered seized and withheld from the public). All told, half a million New Yorkers, black and white, participated in or witnessed the city’s farewell to Lincoln, an event that even the long-hostile New York Herald called “a triumphant procession greater, grander, more genuine than any living conqueror or hero ever enjoyed.”

But even there, local officials showed that some attitudes remained unchanged, and perhaps unchangeable, despite Lincoln’s martyrdom. To the mortification of the city’s progressives, its Democrat-dominated arrangements committee denied an African-American contingent the right to march in the procession honoring the man one of its banners proclaimed as “Our Emancipator.” Stanton ordered that the city find room for these mourners, so New York did—at the back of a four-and-a-half-hour-long line of marchers. By the time the 200 members of the African-American delegations reached the end of the procession near the Hudson River, Lincoln’s remains had left the city.

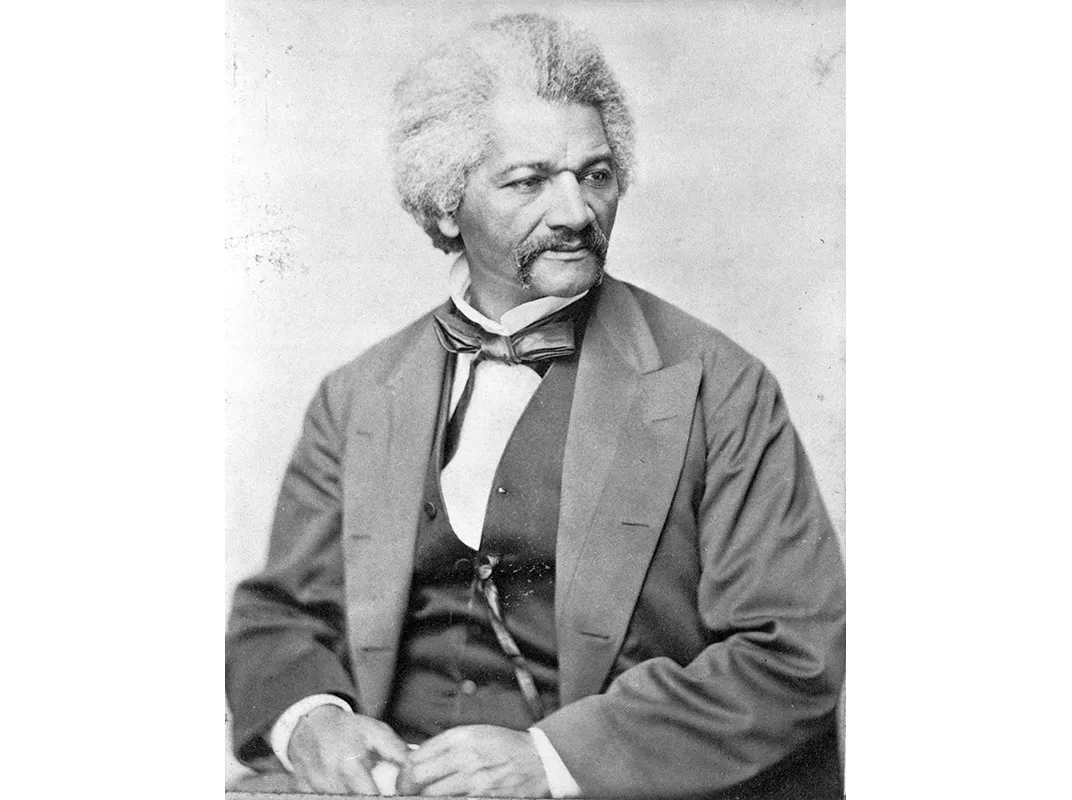

It seemed fitting that the African-American leader Frederick Douglass would rise to deliver an important but largely unpublished eulogy at the Great Hall of Cooper Union, site of the 1860 speech that had helped make Lincoln president. From the same lectern Lincoln had once spoken, the antislavery champion—about whom the president had only recently declared, “There is no man’s opinion that I value more”—told his audience that Lincoln deserved history’s acknowledgment as “the black man’s president.” (Yet this judgment, too, eventually shifted. On the 11th anniversary of the assassination, as the guarantee of equal rights for African-Americans remained unfulfilled, Douglass reassessed Lincoln as “preeminently the white man’s president.”)

Nowhere did the initial, unpredictable response to Lincoln’s death seem more bizarrely insensitive than in the birthplace of secession and civil war: Charleston, South Carolina, where a picture vendor placed on open sale photographs of John Wilkes Booth. Did their appearance signify admiration for the assassin, a resurgence of sympathy for the Lost Cause, or perhaps a manifestation of Southern hatred for the late president? In fact, the motivation may have arisen from the most sustained emotion that characterized the response to Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, and it was entirely nonpartisan and nonsectional: burning curiosity.

How else to explain what came to light when, more than a century later, scholars discovered an unknown trove of Lincoln family pictures long in the possession of the president’s descendants? Here, once housed in a gold-tooled leather album alongside cartes de visite of the Lincoln children, Todd relatives, scenic views, the family’s dog and portraits of Union political and military heroes, a curator found an inexplicably acquired, carefully preserved photograph of the man who had murdered the family patriarch: the assassin himself, John Wilkes Booth.

Related Reads

President Lincoln Assassinated!! The Firsthand Story of the Murder, Manhunt

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/harold2.png)