What’s Changed, and What Hasn’t, in the Town That Inspired ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’

Traveling back in time to visit Harper Lee’s hometown, the setting of her 1960 masterpiece and the controversial sequel hitting bookstores soon

:focal(2377x2377:2378x2378)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/21/10/211037f4-4a9d-4197-a8e7-a2826a16b1ed/julaug2015_f06_mockingbird.jpg)

The twiggy branches of the redbuds were in bloom, the shell-like magnolia petals had begun to twist open, the numerous flowering Bradford pear trees—more blossomy than cherries—were a froth of white, and yet this Sunday morning in March was unseasonably chilly in Monroeville, Alabama. A week before, I had arrived there on a country road. In the Deep South, and Alabama especially, all the back roads seem to lead into the bittersweet of the distant past.

Over on Golf Drive, once a white part of town, Nannie Ruth Williams had risen at 6 in the dim light of a late winter dawn to prepare lunch—to simmer the turnip greens, cook the yams and sweet potatoes, mix the mac and cheese, bake a dozen biscuits, braise the chicken parts and set them with vegetables in the slow cooker. Lunch was seven hours off, but Nannie Ruth’s rule was “No cooking after church.” The food had to be ready when she got home from the Sunday service with her husband, Homer Beecher Williams—“H.B.” to his friends—and anyone else they invited. I hadn’t met her, nor did she yet know that one of the diners that day would be me.

The sixth of 16 children, born on the W. J. Anderson plantation long ago, the daughter of sharecropper Charlie Madison (cotton, peanuts, sugar cane, hogs), Nannie Ruth had a big-family work ethic. She had heard that I was meeting H.B. that morning, but had no idea who I was, or why I was in Monroeville, yet in the Southern way, she was prepared to be welcoming to a stranger, with plenty of food, hosting a meal that was a form of peacemaking and fellowship.

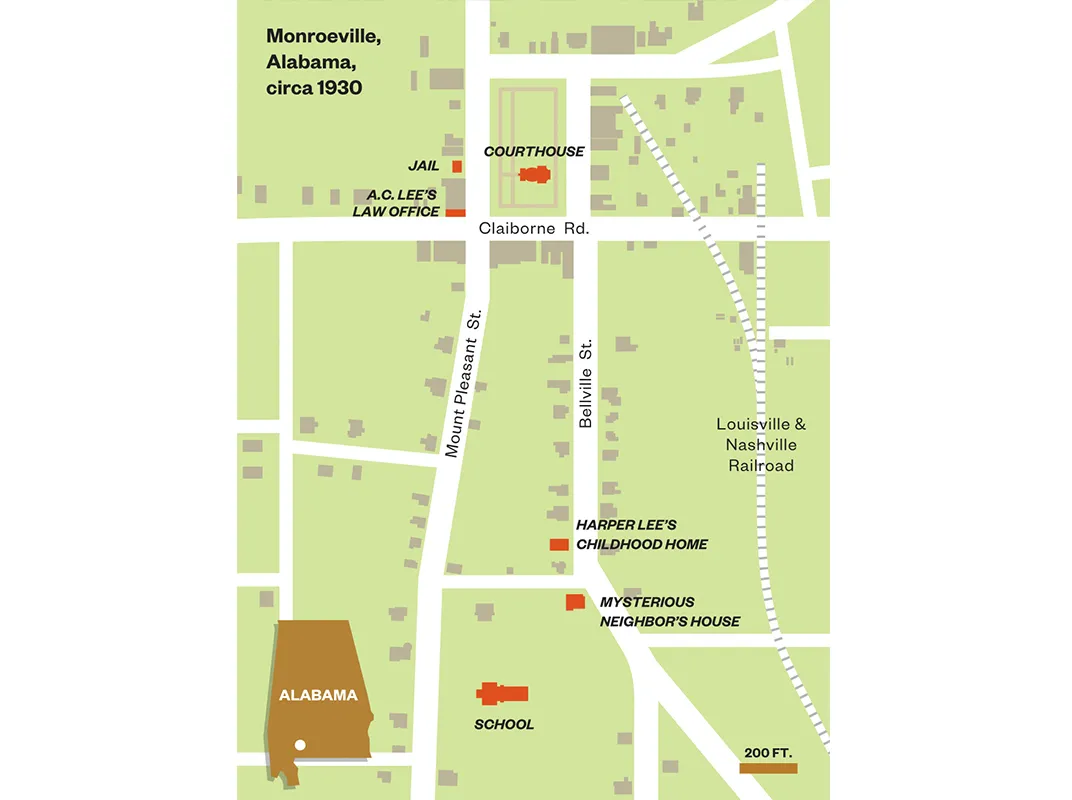

Monroeville styles itself “the Literary Capital of Alabama.” Though the town had once been segregated, with the usual suspicions and misunderstandings that arise from such forced separation, I found it to be a place of sunny streets and friendly people, and also—helpful to a visiting writer—a repository of long memories. The town boasts that it has produced two celebrated writers, who grew up as neighbors and friends, Truman Capote and Harper Lee. Their homes no longer stand, but other landmarks persist, those of Maycomb, the fictional setting of To Kill A Mockingbird. Still one of the novels most frequently taught in American high schools, Lee’s creation has sold more than 40 million copies and been translated into 40 languages.

Among the pamphlets and souvenirs sold at the grandly domed Old Courthouse Museum is Monroeville, The Search for Harper Lee’s Maycomb, an illustrated booklet that includes local history as well as images of the topography and architecture of the town that correspond to certain details in the novel. Harper Lee’s work, published when she was 34, is a mélange of personal reminiscence, fictional flourishes and verifiable events. The book contains two contrasting plots, one a children’s story, the tomboy Scout, her older brother Jem and their friend Dill, disturbed in their larks and pranks by an obscure house-bound neighbor, Boo Radley; and in the more portentous story line, Scout’s father’s combative involvement in the defense of Tom Robinson, the decent black man, who has been accused of rape.

What I remembered of my long-ago reading of the novel was the gusto of the children and their outdoor world, and the indoor narrative, the courtroom drama of a trumped-up charge of rape, a hideous miscarriage of justice and a racial murder. Rereading the novel recently, I realized I had forgotten how odd the book is, the wobbly construction, the arch language and shifting point of view, how atonal and forced it is at times, a youthful directness and clarity in some of the writing mingled with adult perceptions and arcane language. For example, Scout is in a classroom with a new teacher from North Alabama. “The class murmured apprehensively,” Scout tells us, “should she prove to harbor her share of the peculiarities indigenous to that region.” This is a tangled way for a 6-year-old to perceive a stranger, and this verbosity pervades the book.

I am now inclined to Flannery O’Connor’s view of it as “a child’s book,” but she meant it dismissively, while I tend to think that its appeal to youngsters (like that of Treasure Island and Tom Sawyer) may be its strength. A young reader easily identifies with the boisterous Scout and sees Atticus as the embodiment of paternal virtue. In spite of the lapses in narration, the book’s basic simplicity and moral certainties are perhaps the reason it has endured for more than 50 years as the tale of an injustice in a small Southern town. That it appeared, like a revelation, at the very moment the civil rights movement was becoming news for a nation wishing to understand, was also part of its success.

Monroeville had known a similar event, the 1934 trial of a black man, Walter Lett, accused of raping a white woman. The case was shaky, the woman unreliable, no hard evidence; yet Walter Lett was convicted and sentenced to death. Before he was electrocuted, calls for clemency proved successful; but by then Lett had been languishing on Death Row too long, within earshot of the screams of doomed men down the hall, and he was driven mad. He died in an Alabama hospital in 1937, when Harper Lee was old enough to be aware of it. Atticus Finch, an idealized version of A.C. Lee, Harper’s attorney father, defends the wrongly accused Tom Robinson, who is a tidier version of Walter Lett.

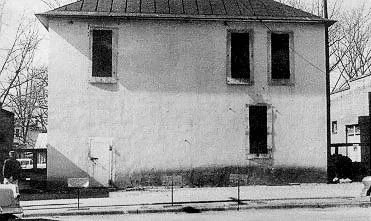

Never mind the contradictions and inconsistencies: Novels can hallow a place, cast a glow upon it and inspire bookish pilgrims—and there are always visitors, who’d read the book or seen the movie. Following the free guidebook Walk Monroeville, they stroll in the downtown historic district, admiring the Old Courthouse, the Old Jail, searching for Maycomb, the locations associated with the novel’s mythology, though they search in vain for locations of the movie, which was made in Hollywood. It is a testament to the spell cast by the novel, and perhaps to the popular film, that the monument at the center of town is not to a Monroeville citizen of great heart and noble achievement, nor a local hero or an iconic Confederate soldier, but to a fictional character, Atticus Finch.

These days the talk in town is of Harper Lee, known locally by her first name, Nelle (her grandmother’s name Ellen spelled backward). Avoiding publicity from the earliest years of her success, she is back in the news because of the discovery and disinterment of a novel she’d put aside almost six decades ago, an early version of the Atticus Finch-Tom Robinson story, told by Scout grown older and looking down the years. Suggesting the crisis of a vulnerable and convicted man in the Old Jail on North Mount Pleasant Avenue, the novel is titled Go Set a Watchman.

“It’s an old book!” Harper Lee told a mutual friend of ours who’d seen her while I was in Monroeville. “But if someone wants to read it, fine!”

Speculation is that the resurrected novel will be sought after as the basis of a new film. The 1962 adaptation of To Kill A Mockingbird, with Gregory Peck’s Oscar-winning performance as Atticus Finch, sent many readers to the novel. The American Film Institute has ranked Atticus as the greatest movie hero of all time (Indiana Jones is number two). Robert Duvall, who at age 30 played the mysterious neighbor, Boo Radley, in the film, recently said: “I am looking forward to reading the [new] book. The film was a pivotal point in my career and we all have been waiting for the second book.”

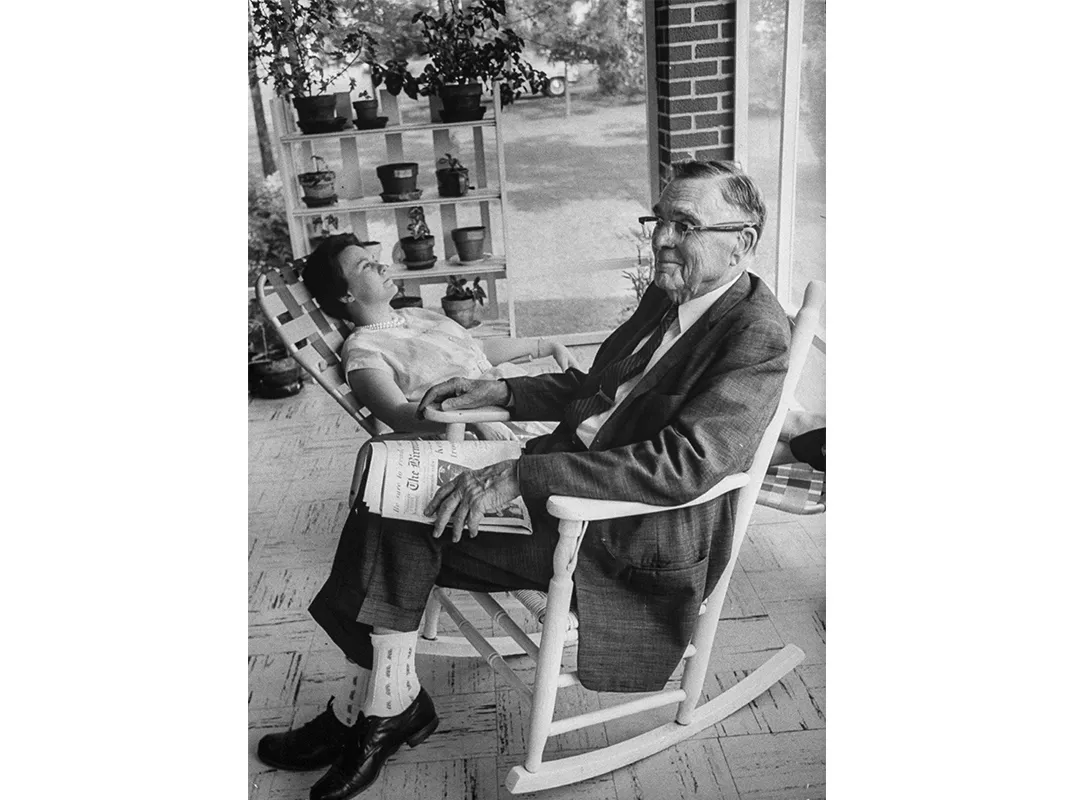

According to biographer Charles Shields, author of Mockingbird: A Portrait of Harper Lee, Nelle started several books after her success in 1960: a new novel, and a nonfiction account of a serial murderer. But she’d abandoned them, and apart from a sprinkling of scribbles, seemingly abandoned writing anything else—no stories, no substantial articles, no memoir of her years of serious collaboration with Truman Capote on In Cold Blood. Out of the limelight, she had lived well, mainly in New York City, with regular visits home, liberated by the financial windfall but burdened—maddened, some people said—by the pressure to produce another book. (Lee, who never married, returned to Alabama permanently in 2007 after suffering a stroke. Her sister Alice, an attorney in Monroeville who long handled Lee’s legal affairs, died this past November at age 103.)

It seems—especially to a graphomaniac like myself—that Harper Lee was perhaps an accidental novelist—one book and done. Instead of a career of creation, a refinement of this profession of letters, an author’s satisfying dialogue with the world, she shut up shop in a retreat from the writing life, like a lottery winner in seclusion. Now 89, living in a care home at the edge of town, she is in delicate health, with macular degeneration and such a degree of deafness that she can communicate only by reading questions written in large print on note cards.

“What have you been doing?” my friend wrote on a card and held it up.

“What sort of fool question is that?” Nelle shouted from her chair. “I just sit here. I don’t do anything!”

She may be reclusive but she is anything but a shrinking violet, and she has plenty of friends. Using a magnifier device, she is a reader, mainly of history, but also of crime novels. Like many people who vanish, wishing for privacy—J.D. Salinger is the best example—she has been stalked, intruded upon, pestered and sought after. I vowed not to disturb her.

**********

Nannie Ruth Williams knew the famous book, and she was well aware of Monroeville’s other celebrated author. Her grandfather had sharecropped on the Faulk family land, and it so happened that Lillie Mae Faulk had married Archulus Julius Persons in 1923 and given birth to Truman Streckfus Persons a little over a year later. After Lillie Mae married a man named Capote, her son changed his name to Truman Capote. Capote had been known in town for his big-city airs. “A smart ass,” a man who’d grown up with him told me. “No one liked him.” Truman was bullied for being small and peevish, and his defender was Nelle Lee, his next-door neighbor. “Nelle protected him,” that man said. “When kids would hop on Capote, Nelle would get ’em off. She popped out a lot of boys’ teeth.”

Capote, as a child, lives on as the character Dill in the novel. His portrayal is a sort of homage to his oddness and intelligence, as well as their youthful friendship. “Dill was a curiosity. He wore blue linen shorts that buttoned to his shirt, his hair was snow-white and stuck to his head like duck-fluff; he was a year my senior but I towered over him.” And it is Dill who animates the subplot, which is the mystery of Boo Radley.

Every year, a highly praised and lively dramatization of the novel is put on by the town’s Mockingbird Players, with dramatic courtroom action in the Old Courthouse. But Nannie Ruth smiled when she was asked whether she’d ever seen it. “You won’t find more than four or five black people in the audience,” a local man told me later. “They’ve lived it. They’ve been there. They don’t want to be taken there again. They want to deal with the real thing that’s going on now.”

H.B. Williams sighed when any mention of the book came up. He was born in a tenant farming family on the Blanchard Slaughter plantation where “Blanchie,” a wealthy but childless white landowner, would baby-sit for the infant H.B. while his parents worked in the fields, picking and chopping cotton. This would have been at about the time of the Walter Lett trial, and the fictional crime of Mockingbird—mid-’30s, when the Great Depression gripped “the tired old town” of the novel, and the Ku Klux Klan was active, and the red clay of the main streets had yet to be paved over.

After the book was published and became a best seller, H.B., then a school principal, was offered the job of assistant principal, and when he refused, pointing out that it was a demotion, he was fired. He spent years fighting for his reinstatement. His grievance was not a sequence of dramatic events like the novel, it was just the unfairness of the Southern grind. The pettifogging dragged on for ten years, but H.B. was eventually triumphant. Yet it was an injustice that no one wanted to hear about, unsensational, unrecorded, not at all cinematic.

In its way, H.B.’s exhausting search for justice resembles that of the public-interest attorney Bryan Stevenson in his quest to exonerate Walter McMillian, another citizen of Monroeville. This was also a local story, but a recent one. One Saturday morning in 1986, Ronda Morrison, a white 18-year-old clerk at Jackson Cleaners, was found shot to death at the back of the store. This was in the center of town, near the Old Courthouse made famous 26 years earlier in the novel about racial injustice. In this real case, a black man, Walter McMillian, who owned a local land-clearing business, was arrested, though he’d been able to prove he was nowhere near Jackson Cleaners that day. The trial, moved to mostly white Baldwin County, lasted a day and a half. McMillian was found guilty and sentenced to death.

It emerged that McMillian had been set up; the men who testified against him had been pressured by the police, and later recanted. Bryan Stevenson—the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, who today is renowned for successfully arguing before the Supreme Court in 2012 that lifetime sentences for juveniles convicted of homicide constituted cruel and unusual punishment—had taken an interest in the case. He appealed the conviction, as he relates in his prize-winning account, Just Mercy (2014). After McMillian had been on death row for five years, his conviction was overturned; he was released in 1993. The wheels of justice grind slowly, with paper shuffling and appeals. Little drama, much persistence. In the town with a memorial to Atticus Finch, not Bryan Stevenson.

And that’s the odd thing about a great deal of a certain sort of Deep South fiction—its grotesquerie and gothic, its high color and fantastication, the emphasis on freakishness. Look no further than Faulkner or Erskine Caldwell, but there’s plenty in Harper Lee too, in Mockingbird, the Boo Radley factor, the Misses Tutti and Frutti, and the racist Mrs. Dubose, who is a morphine addict: “Her face was the color of a dirty pillowcase and the corners of her mouth glistened with wet which inched like a glacier down the deep grooves enclosing her chin.” This sort of prose acts as a kind of indirection, dramatizing weirdness as a way of distracting the reader from day to day indignities.

Backward-looking, few Southern writers concern themselves with the new realities, the decayed downtown, the Piggly Wiggly and the pawn shops, the elephantine Walmart, reachable from the bypass road, where the fast-food joints have put most of the local eateries out of business (though AJ’s Family Restaurant, and the Court House Café in Monroeville remain lively). Monroeville people I met were proud of having overcome hard times. Men of a certain age recalled World War II: Charles Salter, who was 90, served in the 78th Infantry, fighting in Germany, and just as his division reached the west bank of the Rhine he was hit by shrapnel in the leg and foot. Seventy years later he still needed regular operations. “The Depression was hard,” he said. “It lasted here till long after the war.” H.B. Williams was drafted to fight in Korea. “And when I returned to town, having fought for my country, I found I couldn’t vote.”

Some reminiscences were of a lost world, like those of the local columnist, George Thomas Jones, who was 92 and remembered when all the roads of the town were red clay, and how as a drugstore soda jerk he was sassed by Truman Capote, who said, “I sure would like to have something good, but you ain’t got it....A Broadway Flip.” Young George faced him down, saying, “Boy, I’ll flip you off that stool!” Charles Johnson, a popular barber in town, worked his scissors on my head and told me, “I’m from the child abuse era—hah! If I was bad my daddy would tell me to go out and cut a switch from a bridal wreath bush and he’d whip my legs with it. Or a keen switch, more narrah. It done me good!”

Mr. Johnson told me about the settlement near the areas known as Franklin and Wainwright, called Scratch Ankle, famous for inbreeding. The poor blacks lived in Clausell and on Marengo Street, the rich whites in Canterbury, and the squatters up at Limestone were to be avoided. But I visited Limestone just the same; the place was thick with idlers and drunks and barefoot children, and a big toothless man named LaVert stuck his finger in my face and said, “You best go away, mister—this is a bad neighborhood.” There is a haunted substratum of darkness in Southern life, and though it pulses through many interactions, it takes a long while to perceive it, and even longer to understand.

The other ignored aspect of life: the Deep South still goes to church, and dresses up to do so. There are good-sized churches in Monroeville, most of them full on Sundays, and they are sources of inspiration, goodwill, guidance, friendship, comfort, outreach and snacks. Nannie Ruth and H.B. were Mount Nebo Baptists, but today they’d be attending the Hopewell C.M.E. Church because the usual pianist had to be elsewhere, and Nannie Ruth would play the piano. The pastor, the Rev. Eddie Marzett, had indicated what hymns to plan for. It was “Women’s Day.” The theme of the service was “Women of God in these Changing Times,” with appropriate Bible readings and two women preachers, the Rev. Marzett taking a back pew in his stylish white suit and tinted glasses.

**********

Monroeville is like many towns of its size in Alabama—indeed the Deep South: a town square of decaying elegance, most of the downtown shops and businesses closed or faltering, the main industries shut down. I was to discover that To Kill A Mockingbird is a minor aspect of Monroeville, a place of hospitable and hard-working people, but a dying town, with a population of 6,300 (and declining), undercut by NAFTA, overlooked by Washington, dumped by manufacturers like Vanity Fair Mills (employing at its peak 2,500 people, many of them women) and Georgia Pacific, which shut down its plywood plant when demand for lumber declined. The usual Deep South challenges in education and housing apply here, and almost a third of Monroe County (29 percent) lives in poverty.

“I was a traveling bra and panty salesman,” Sam Williams told me. “You don’t see many of those nowadays.” He had worked for Vanity Fair for 28 years, and was now a potter, hand-firing cups and saucers of his own design. But he had lucked out in another way: Oil had been found near his land—one of Alabama’s surprises—and his family gets a regular small check, divided five ways among the siblings, from oil wells on the property. His parting shot to me was an earnest plea: “This is a wonderful town. Talk nice about Monroeville.”

Willie Hill had worked for Vanity Fair for 34 years and was now unemployed. “They shut down here, looking for cheap labor in Mexico.” He laughed at the notion that the economy would improve because of the Mockingbird pilgrims. “No money in that, no sir. We need industry, we need real jobs.”

“I’ve lived here all my life—81 years,” a man pumping gas next to me said out of the blue, “and I’ve never known it so bad. If the paper mill closes, we’ll be in real trouble.” (Georgia-Pacific still operates three mills in or near Monroeville.) Willie Hill’s nephew Derek was laid off in 2008 after eight years fabricating Georgia-Pacific plywood. He made regular visits to Monroeville’s picturesque and well-stocked library (once the LaSalle Hotel: Gregory Peck had slept there in 1962 when he visited to get a feel for the town), looking for jobs on the library’s computers and updating his résumé. He was helped by the able librarian, Bunny Hines Nobles, whose family had once owned the land where the hotel stands.

**********

Selma is an easy two-hour drive up a country road from Monroeville. I had longed to see it because I wanted to put a face to the name of the town that had become a battle cry. It was a surprise to me—not a pleasant one, more of a shock, and a sadness. The Edmund Pettus Bridge I recognized from newspaper photos and the footage of Bloody Sunday—protesters being beaten, mounted policemen trampling marchers. That was the headline and the history. What I was not prepared for was the sorry condition of Selma, the shut-down businesses and empty once-elegant apartment houses near the bridge, the whole town visibly on the wane, and apart from its mall, in desperate shape, seemingly out of work. This decrepitude was not a headline.

Just a week before, on the 50th anniversary of the march, President Obama, the first lady, a number of celebrities, civil rights leaders, unsung heroes of Selma and crowders of the limelight had observed the anniversary. They invoked the events of Bloody Sunday, the rigors of the march to Montgomery, and the victory, the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

But all that was mostly commemorative fanfare, political theater and sentimental rage. The reality, which was also an insult, was that these days in this city which had been on the front line of the voting rights movement, voting turnout among the 18-to-25 age group was discouragingly low, with the figures even more dismal in local elections. I learned this at the Interpretive Center outside town, where the docents who told me this shook their heads at the sorry fact. After all the bloodshed and sacrifice, voter turnout was lagging, and Selma itself was enduring an economy in crisis. This went unremarked by the president and the civil rights stalwarts and the celebrities, most of whom took the next plane out of this sad and supine town.

Driving out of Selma on narrow Highway 41, which was lined by tall trees and deep woods, I got a taste of the visitable past. You don’t need to be a literary pilgrim; this illuminating experience of country roads is reason enough to drive through the Deep South, especially here, where the red clay lanes—brightened and brick-hued from the morning rain—branch from the highway into the pines; crossing Mush Creek and Cedar Creek, the tiny flyspeck settlements of wooden shotgun shacks and old house trailers and the white-planked churches; past the roadside clusters of foot-high ant hills, the gray witch-hair lichens trailing from the bony limbs of dead trees, a mostly straight-ahead road of flat fields and boggy pinewoods and flowering shrubs, and just ahead a pair of crows hopping over a lump of crimson road-kill hash.

I passed through Camden, a ruinous town of empty shops and obvious poverty, just a flicker of beauty in some of the derelict houses, an abandoned filling station, the white-washed clapboards and a tiny cupola of old Antioch Baptist Church (Martin Luther King Jr. had spoken here in April 1965, inspiring a protest march that day and the next), the imposing Camden public library, its facade of fat white columns; and then the villages of Beatrice—Bee-ah-triss—and Tunnel Springs. After all this time-warp decay, Monroeville looked smart and promising, with its many churches and picturesque courthouse and fine old houses. Its certain distinction and self-awareness and its pride were the result of its isolation. Nearly 100 miles from any city, Monroeville had always been in the middle of nowhere—no one arrived by accident. As Southerners said, You had to be going there to get there.

Hopewell C.M.E. Church—in a festive Women’s Day mood—was adjacent to the traditionally black part of town, Clausell. The church’s sanctuary had served as a secret meeting place in the 1950s for the local civil rights movement, many of the meetings presided over by the pastor, R.V. McIntosh, and a firebrand named Ezra Cunningham, who had taken part in the Selma march. All this information came from H.B. Williams, who had brought me to a Hopewell pew.

After the hymns (Nannie Ruth Williams on the piano, a young man on drums), the announcements, the two offerings, the readings from Proverbs 31 (“Who can find a virtuous woman, for her price is far above rubies”), and prayers, Minister Mary Johnson gripped the lectern and shouted: “Women of God in these Changing Times, is our theme today, praise the Lord,” and the congregation called out “Tell it, sister!” and “Praise his name!”

Minister Mary was funny and teasing in her sermon, and her message was simple: Be hopeful in hard times. “Don’t look in the mirror and think, ‘Lord Jesus, what they gonna think ’bout my wig?’ Say ‘I’m coming as I am!’ Don’t matter ’bout your dress—magnify the Lord!” She raised her arms and in her final peroration said, “Hopelessness is a bad place to be. The Lord gonna fee-all you with hope. You might not have money—never mind. You need the Holy Spirit!”

Afterward, the hospitable gesture, my invitation to lunch at the Williams house, a comfortable bungalow on Golf Drive, near the gates to Whitey Lee Park, which was off-limits to blacks until the 1980s, and the once-segregated golf course. We were joined at the table by Arthur Penn, an insurance man and vice president of the local NAACP branch, and his son Arthur Penn Jr.

I raised the subject of Mockingbird, which made Nannie Ruth shrug. Arthur Senior said, “It’s a distraction. It’s like saying, ‘This is all we have. Forget the rest.’ It’s like a 400-pound comedian on stage telling fat jokes. The audience is paying more attention to the jokes than to what they see.”

In Monroeville, the dramas were intense but small-scale and persistent. The year the book came out all the schools were segregated and they remained so for the next five years. And once the schools were integrated in 1965, the white private school Monroe Academy was established not long after. Race relations had been generally good, and apart from the Freedom Riders from the North (which Nelle Lee disparaged at the time as agitators), there were no major racial incidents, only the threat of them.

“Most whites thought, ‘You’re good in your place. Stay there and you’re a good nigger,’” H.B. said. “Of course it was an inferior situation, a double standard all over.”

And eating slowly he was provoked to a reminiscence, recalling how in December 1959 the Monroeville Christmas parade was canceled, because the Klan had warned that if the band from the black high school marched with whites, there would be blood. To be fair, all the whites I spoke to in Monroeville condemned this lamentable episode. Later, in 1965, the Klan congregated on Drewry Road, wearing sheets and hoods, 40 or 50 of them, and they marched down Drewry to the Old Courthouse. “Right past my house,” H.B. said. “My children stood on the porch and called out to them.” This painful memory was another reason he had no interest in the novel, then in its fifth year of bestsellerdom.

“This was a white area. Maids could walk the streets, but if the residents saw a black man they’d call the sheriff, and then take you to jail,” Arthur Penn said.

And what a sheriff. Up to the late 1950s, it was Sheriff Charlie Sizemore, noted for his bad temper. How bad? “He’d slap you upside the head, cuss you out, beat you.”

One example: A prominent black pastor, N.H. Smith, was talking to another black man, Scott Nettles, on the corner of Claiborne and Mount Pleasant, the center of Monroeville, and steps from the stately courthouse, just chatting. “Sizemore comes up and slaps the cigarette out of Nettles’ mouth and cusses him out, and why? To please the white folks, to build a reputation.”

That happened in 1948, in this town of long memories.

H.B. and Arthur gave me other examples, all exercises in degradation, but here is a harmonious postscript to it all. In the early ’60s, Sizemore—a Creek Indian, great-grandson to William Weatherford, Chief Red Eagle—became crippled and had a conversion. As an act of atonement, Sizemore went down to Clausell, to the main house of worship, Bethel Baptist Church, and begged the black congregation for forgiveness.

Out of curiosity, and against the advice of several whites I met in town, I visited Clausell, the traditionally black section of town. When Nelle Lee was a child, the woman who bathed and fed her was Hattie Belle Clausell, the so-called mammy in the Lee household, who walked from this settlement several miles every day to the house on South Alabama Avenue in the white part of town (the Lee house is now gone, replaced by Mel’s Dairy Dream and a defunct swimming pool-supply store). Clausell was named for that black family.

I stopped at Franky D’s Barber and Style Shop on Clausell Road, because barbers know everything. There I was told that I could find Irma, Nelle’s former housekeeper, up the road, “in the projects.”

The projects was a cul-de-sac of brick bungalows, low-cost housing, but Irma was not in any of them.

“They call this the ’hood,” Brittany Bonner told me—she was on her porch, watching the rain come down. “People warn you about this place, but it’s not so bad. Sometimes we hear guns—people shooting in the woods. You see that cross down the road? That’s for the man they call ‘James T’—James Tunstall. He was shot and killed a few years ago right there, maybe drug-related.”

A white man in Monroeville told me that Clausell was so dangerous that the police never went there alone, but always in twos. Yet Brittany, 22, mother of two small girls, said that violence was not the problem. She repeated the town’s lament: “We have no work, there are no jobs.”

Brittany’s great-aunt Jacqueline Packer thought I might find Irma out at Pineview Heights, down Clausell Road, but all I found were a scattering of houses, some bungalows and many dogtrot houses, and rotting cars, and a sign on a closed roadside café, “Southern Favorites—Neckbones and Rice, Turkey Necks and Rice,” and then the pavement ended and the road was red clay, velvety in the rain, leading into the pinewoods.

Back in town I saw a billboard with a stern message: “Nothing in this country is free. If you’re getting something without paying for it, Thank a Taxpayer.” Toward the end of my stay in Monroeville, I met the Rev. Thomas Lane Butts, former pastor of the First United Methodist Church, where Nelle Lee and her sister, Alice, had been members of his congregation, and his dear friends.

“This town is no different from any other,” he told me. He was 85, and had traveled throughout the South, and knew what he was talking about. Born ten miles east in what he called “a little two-mule community” of Bermuda (Ber-moo-dah in the local pronunciation), his father had been a tenant farmer—corn, cotton, vegetables. “We had no land, we had nothing. We didn’t have electricity until I was in the 12th grade, in the fall of 1947. I studied by oil lamp.”

The work paid off. After theology studies at Emory and Northwestern, and parishes in Mobile and Fort Walton Beach, Florida, and civil rights struggles, he became pastor of this Methodist church.

“We took in racism with our mother’s milk,” he said. But he’d been a civil rights campaigner from early on, even before 1960 when in Talladega he met Martin Luther King Jr. “He was the first black person I’d met who was not a field hand,” he said. “The embodiment of erudition, authority and humility.”

Rev. Butts had a volume of Freud in his lap the day I met him, searching for a quotation in Civilization and Its Discontents.

I told him the essay was one of my own favorites, for Freud’s expression about human pettiness and discrimination, “the narcissism of minor differences”—the subtext of the old segregated South, and of human life in general.

His finger on the page, Rev. Butts murmured some sentences, “‘The element of truth behind all this...men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved...can defend themselves...a powerful share of aggressiveness...’ Ah here it is. ‘Homo homini lupus...Man is a wolf to man.’”

That was the reality of history, as true in proud Monroeville as in the wider world. And that led us to talk about the town, the book, the way things are. He valued his friendship with H.B. Williams: the black teacher, the white clergyman, both in their 80s, both of them civil rights stalwarts. He had been close to the Lee family, had spent vacations in New York City with Nelle, and still saw her. An affectionately signed copy of the novel rested on the side table, not far from his volume of Freud.

“Here we are,” he intoned, raising his hands, “tugged between two cultures, one gone and never to return, the other being born. Many things here have been lost. To Kill A Mockingbird keeps us from complete oblivion.”

Related Reads

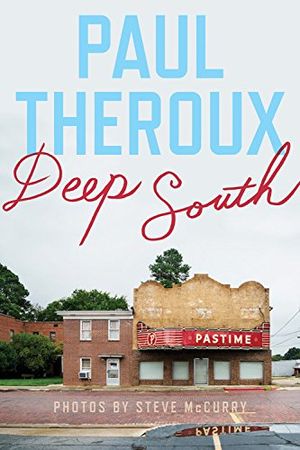

Deep South: Four Seasons on Back Roads