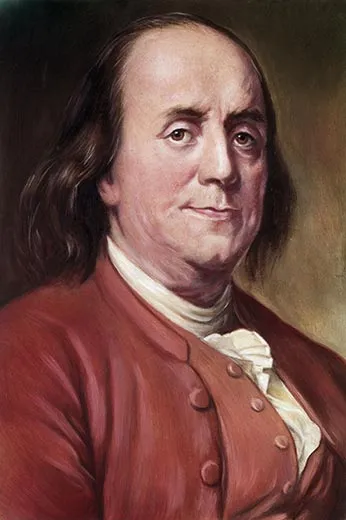

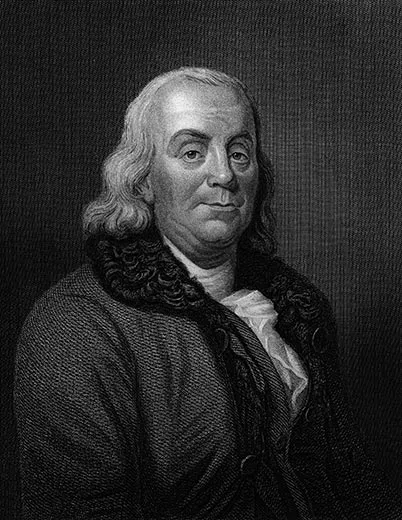

When Ben Franklin Met the Battlefield

Most famous today as a founding father, inventor and diplomat, Franklin also commanded troops during the French and Indian War

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Benjamin-Franklin-black-and-white-portrait-631.jpg)

Weapons ready, slogging into the deserted village, the men and their commander were appalled at what they saw: dead soldiers and civilians and evidence of a hasty retreat. The commander ordered quick fortifications against further attack, then burial parties.

The orders came from an unlikely figure: Benjamin Franklin, 50 years old, already rich, retired from his printing business and notably famous for his inventions.

He had received the Copley Medal from the Royal Society of London in 1753 for his “curious Experiments and Observations on Electricity” and founded a college in Philadelphia, as well as a lending library and other civic institutions. Now the otherwise unathletic Franklin found himself in the role of military chief, leading 170 men deep into countryside overrun by Shawnee, Delaware and Frenchmen who had been attacking English settlements with abandon.

By 1756, the French and Indian War was in full swing, especially in Pennsylvania: Gen. Edward Braddock’s British and American army had been destroyed along the Monongahela River to the west in July; marauding Indians had struck within 80 miles of Philadelphia; and 400 settlers had been killed in the region since summer and others had been taken prisoner. Gnadenhütten (“huts of grace,” at present-day Weissport), a Moravian settlement, had been attacked by Indians in November, then again in early January after militia had been sent there to fortify it. The whole Lehigh Valley was exposed. It fell to Franklin to slow the flow of refugees trudging toward Philadelphia and halt the swelling enemy, bent on pressing the English to the Atlantic.

Franklin was made a military commander because of his experience in the Pennsylvania Assembly. Having lived through clashes between the French and British in the 1740s, he understood the importance of a staunch defense and wrote a bill in 1755 calling for the creation of a militia. Franklin had helped General Braddock the year before, so when news arrived of new raids by the French and Indians in the 70 mile stretch of frontier from Bethlehem to Reading, the Pennsylvania Colony’s governor, Robert Morris, felt obliged to turn to him to bolster the frontier. With scant military training, Franklin nonetheless became the most senior military leader in a critical part of British America.

Accompanying Franklin as aide-de-camp was his 25-year-old son, William, who had served in King George’s War as a teenager and also helped supply Braddock eight months earlier. William, who was more adept at military arts than his father, assisted Franklin significantly. The two would later drift apart (William became an Anglophile and Tory during the Revolution), but now father and son worked hand in glove controlling the troops, building fortifications and warding off attack.

On January 15, Franklin began his march toward Gnadenhütten to build a fort that would blunt further French and Indian aggression and protect settlers. With cavalry, infantry and five Conestoga wagons, he led his troops up trails along the Lehigh River, flankers well out to the sides and scouts in front, acutely aware of the Indians’ proclivity to ambush. Gnadenhütten was just beyond Lehigh Valley’s northern border—a long ridge called Blue Mountain—and just outside Lehigh Gap, a cleft cut by the river and a natural artery for travel or invasion. Negotiating the gap was especially trying. Capt. Thomas Lloyd, who served under Franklin , noted in his diary: “The narrow path through the mountains made by the Lehigh where the rocks overhang the road on each side . . . render it practicable for a very small number to destroy a thousand.”

Franklin’s force warded off attack and arrived safely, if cold and wet, at the ruined settlement. After burying the dead, the next day the troops set about erecting a stockade. Franklin proved an able commander. He had the men build a simple 125- by 50-foot fort of felled pines with 18-foot-high walls, and had carpenters erect a platform several feet above ground on which soldiers could stand and fire through loopholes. He led patrols to rout out Indians. He issued succinct orders for companies to bolster nearby settlements, hasten supplies and build two additional forts 15 miles to the east and west. Throughout the Gnadenhütten campaign, as was his wont, Franklin had a keen eye for improvement. When attendance slacked at daily prayer, Franklin suggested to the Rev. Charles Beatty that unless the clergyman found it offensive, he would order the daily ration of rum be made available only at the conclusion of divine service; attendance jumped. He suggested that men use tethered dogs for flanking and scouting duties, unleashing them when enemy were spotted.

Ever curious even on a military mission, Franklin noted in his autobiography the beneficial ventilation of stone buildings in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and discoursed with Moravian leaders about their attitudes toward violence (they would fight only if attacked) and the custom of sometimes arranging marriage by lot—at this last Franklin expressed skepticism but admitted that leaving the choice to individuals could lead as easily to unhappy unions.

Franklin’s military service was dangerous, wearying, cold and wet, and there were times when he placed himself in harm’s way. But his service was also tinged with more than a little politics. Franklin was an important member of the Pennsylvania Assembly. In his bill to raise a militia, he was careful to include the democratic principle that men would elect their officers. He also served without pay. For all of this, he grew ever more popular among Pennsylvanians and unpopular with Thomas Penn, the colony’s disliked London-based proprietor, and Governor Morris. Both feared Franklin might commandeer the militia and, Caesar-like, march on Philadelphia to seize the government.

On February 2, Morris called for a meeting of the Assembly in Philadelphia. Franklin and his son set off for the capital city, relinquishing command of the Gnadenhütten garrison. About one day out, Franklin heard that citizens planned to greet him and march with him into the city. Franklin, who since a young man had striven for humility, was aghast. He quickened his pace to arrive at night, thus quashing a military show.

University of California professor Alan Houston, author of Benjamin Franklin and the Politics of Improvement, discovered copies of 18 previously unknown Franklin letters written during his military service. Houston says the foray into the war-ravaged territory expanded Franklin’s appreciation of the frontier as a source of growth, strength, and wealth. “Franklin’s life was spent in cities: Boston, Philadelphia, London, Paris. But he considered the western frontier a vital interest and in need of vigorous defense,” he says. “It also reinforced Franklin’s notion – especially in the ‘rum’ affair, that even if individuals had questionable motives, they could still be organized to effect a laudable end. Practicality was a Franklin hallmark.”

Within weeks of his arrival in Philadelphia, Franklin, who was deputy postmaster general for several colonies, set off on an inspection tour of Virginia. From there he sailed to New York to meet Lord Loudoun, the new military commander in chief of the colonies sent by King George. Then the Assembly—even more disgruntled with Penn in London—asked Franklin to be their representative to the British government. Franklin agreed, set sail within months and did not return to America for five years.

Houston believes the Gnadenhütten campaign is largely forgotten today because, he says, “being a soldier and commander does not fit our image of Franklin. We recall the kite flier, the clever writer of Poor Richard’s Almanack, the organizer of civic improvements and the sage of the Declaration of Independence debate. Military chief does not seem to be a notion we want to place among these.”