Why a Walk Along the Beaches of Normandy Is the Ideal Way to Remember D-Day

Follow in the footsteps of legendary reporter Ernie Pyle to get a real feel for the events that took place 70 years ago

On a brilliant, spring morning in Normandy, the beach at Colleville-sur-Mer is peaceful. Tall grasses sway in the breeze, sunlight dapples the water, and in the distance, a boat glides lazily along the English Channel.

Only a sign on the hill overlooking the shore suggests that this is anything but a bucolic, seaside resort area: Omaha Beach.

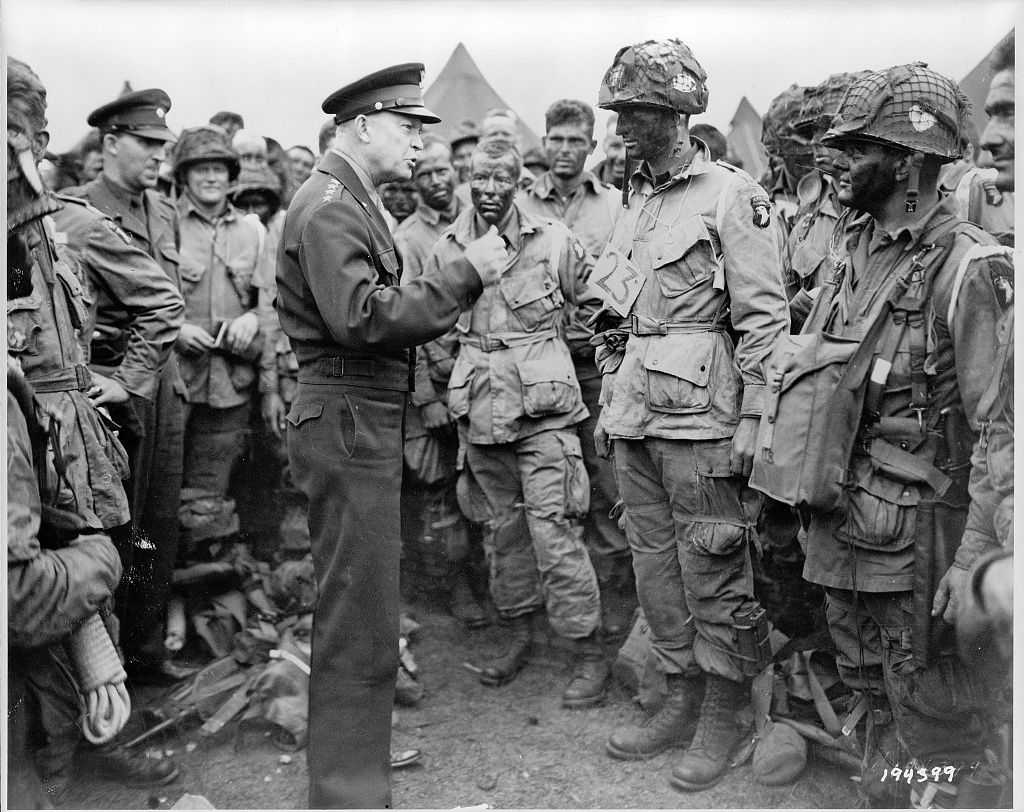

Seventy years ago, this place was a hellish inferno of noise, smoke and slaughter. Here along an approximately five mile stretch of shoreline, what commanding General Dwight Eisenhower called "the great crusade" to liberate Western Europe from Nazi domination, foundered. Had the men of the American 1st and 29th Divisions, supported by engineers and Rangers, not rallied and battled their way through the fierce German defenses along this beach, the outcome of the entire invasion might have been in doubt.

From films such as The Longest Day to Saving Private Ryan, from books by Cornelius Ryan to Stephen Ambrose, the story of the horror and heroism of Omaha Beach has been told and retold. I am here on the eve of the 70th anniversary of D-Day, June 6, 1944, to follow in the footsteps of one of the battles earliest chroniclers: Ernie Pyle, a correspondent for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain who at the time of the invasion was already a celebrity. In fact, when he landed here on June 7, Hollywood was already planning a movie based on his stories, which would be released in 1945 as The Story of G.I. Joe, with Burgess Meredith playing the role of Pyle.

The real Pyle was 43 years old in June 1944 and already a veteran. The Indiana native’s coverage of the campaigns in North Africa, Sicily and Italy had earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 1944 and a vast audience. “He was at the zenith of his popularity,” says Owen V. Johnson, a professor at Indiana University’s School of Journalism (the offices of which are in Ernie Pyle Hall). According to Johnson, an estimated one out of six Americans read Pyle's columns, which appeared four or five times a week during the war.

Perhaps most importantly, at least to the columnist himself, he had earned the respect of the front line American soldiers whose dreary, dirty and sometimes terrifying lives he captured accurately and affectionately.

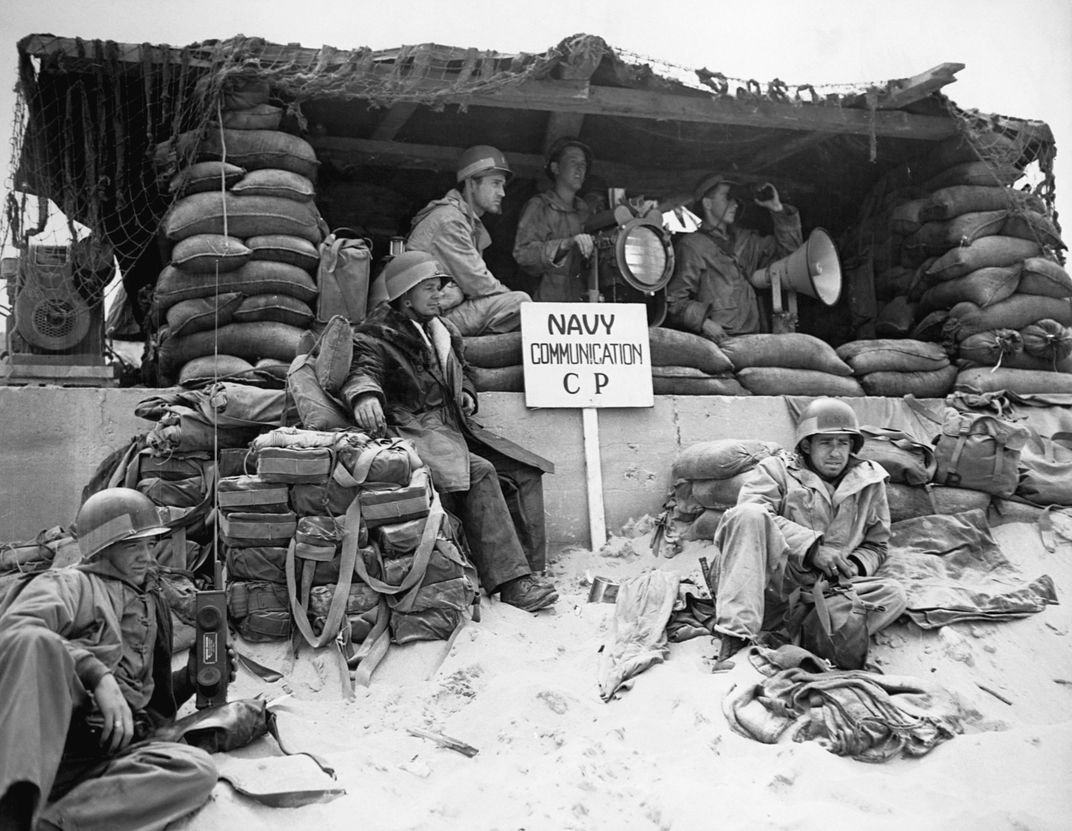

There were fewer more terrifying hours than those endured by the first waves at Omaha Beach on June 6. Only a handful of correspondents were with the assault troops on D-Day. One of them was Pyle's colleague and friend, photographer Robert Capa, whose few surviving photos of the fighting on Omaha have become iconic. When Pyle landed the next morning, the fighting had pretty much stopped but the wreckage was still smoldering. What he decided to do in order to communicate to his readers back home what had happened at this place, not yet even recognized by its invasion code name of Omaha Beach, resulted in some of the most powerful reporting he would produce.

He simply took a walk and wrote what he saw. “It was if he had a video camera in his head,” Johnson said. “He uses words so efficiently...he allows you to gaze and think, just as he did as he walked along.”

I am accompanied for my walk by Claire Lesourd, a licensed, English-speaking tour guide and D-Day expert, who has been giving tours here since 1995. We are heading from east to west, about 1.5 miles, the same length Pyle guessed he had walked along the same beach in 1944.

What he saw that day was a shoreline covered in the litter of battle and the personal effects of men already dead: “A long line of personal anguish,” as he memorably called it.

What I see is emptiness. Aside from a few hikers, we walk alone on a seemingly unending stripe of sand, riven by rivulets of water and sandbars to the water’s edge, which is at this time of day about 600 yards from the low, sandy embankments where the G.I.s—or at least those who made it that far—found some shelter.

My original thought had been to follow Pyle’s lead and wander alone, allowing me to observe and reflect.

But Paul Reed, the British author of Walking D-Day, warned that I could waste a lot of time on areas where there was no fighting. He recommended getting a rental car, which would allow me to visit as many of the significant invasion sites as possible: In addition to Omaha, these would include Utah Beach to the west, where American forces staged a far less bloody and more efficient operation; and Pointe du Hoc, the promontory between the two American beaches that U.S. Army Rangers scaled to knock out German artillery and observation posts.

Reed was right. My reluctance about tooling around in a car in a foreign country proved unfounded. Besides driving on the same side of the road as we do, the French have exceptionally well maintained and marked roads. And in Normandy at least, English is spoken everywhere. So I was indeed able to successfully navigate the entire D-Day area on my own (often relying on nothing more than road signs). I visited the village of St. Mere Eglise—which was liberated by U.S. paratroopers on D-Day—as well as some of the approximately 27 area museums that help deepen one’s understanding of the titanic events that took place here. (I only wish I had had an extra day or two to visit the British invasion beaches, Gold and Sword—which is where the official 70th anniversary observations will be held—and Juno, the Canadian beach.)

At Omaha, I thought all I would need is my notebook and my imagination. A quick re-reading of Pyle’s stories before the walk and some help from Reed’s field guide would suffice. A friend of mine from New York had done just that a few years ago, with less planning than I, and pronounced the experience capital.

But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that the detail and context a well-informed guide could bring would be helpful, if only for my ability to tell this story. Claire proved to be an excellent choice, although she is by no means the only one. There are dozens of competent guides: while they’re not cheap (Ms. LeSourd charges 200€ for a half-day and 300€ for a full-day tour), the time she and I spent walking Omaha proved invaluable—and unforgettable.

On Omaha Beach, monuments to the battle and subsequent carnage are spread out discretely, near the location of the “draws” (paths) that lead up from the beach.

What we know today as Omaha Beach was once called La Plage de Sables D'or; the Beach of the Golden Sands. A century ago, holiday cottages and villas dotted the shore, as well as a railroad line that connected to Cherbourg, then the main junction from Paris. The area attracted artists, including one of the founders of the pointillist school of painters, George Seurat. One of his more famous paintings, Port-en-Bessin, Outer Harbor at High Tide, depicts the nearby seaside village where I stayed the previous night (at the Omaha Beach Hotel).

Much of that was gone by 1944. The Germans, bracing for the attack they were sure would come somewhere along the French coast, demolished the summer homes of Colleville and nearby Vierville sur Mer, minus one Gothic-looking structure whose turret still peaks out from beyond the bike path that runs along the beach road. The Nazis didn't have time to blow that one up (the current owner, Claire tells me, uses the bunker that the Germans built underneath the house as a wine cellar.)

Despite the tranquility of the beach today, it is sobering to look up at the high bluffs overhead and realize that 70 years ago, these wooded hills bristled with weapons—aimed at you. According to Reed, the Germans had at least 85 heavy weapons and machine guns positioned on the high ground, enabling them to rain down about 100,000 rounds a minute. Claire tells me that a few years ago she was escorting a veteran returning to Omaha Beach for the first time since June 6, 1944. Seeing it clearly, without the smoke, noise or adrenaline of battle, he suddenly dropped to his knees and began weeping. "He looked at me,” she recalls, “and said, `I don't know how any of us survived.’"

Pyle said pretty much the same thing. “It seemed to me a pure miracle that we ever took the beach at all,” he wrote.

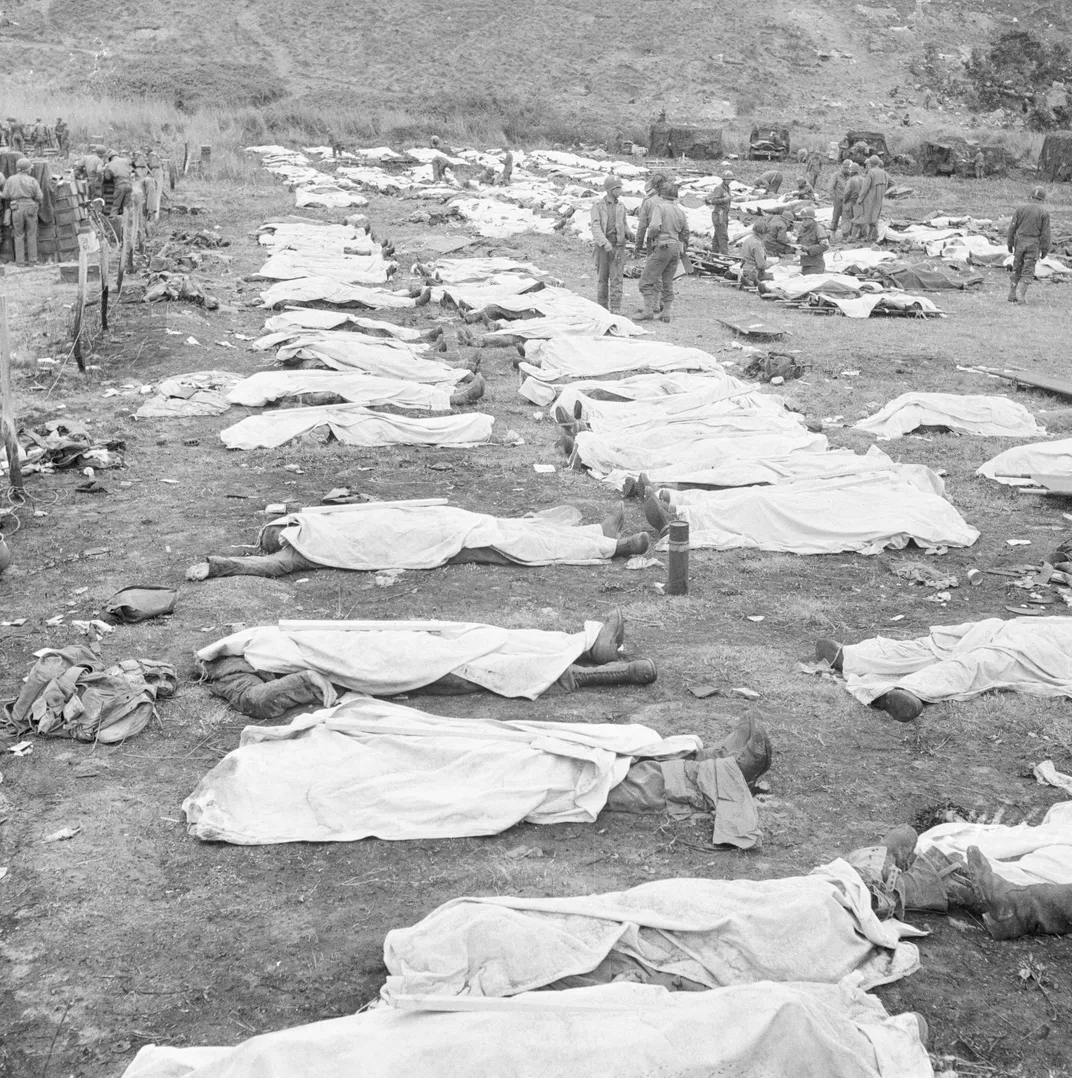

Most of the approximately 2,000 men killed that morning were buried in temporary cemeteries. Many would have their final resting place in the American Cemetery, located on 172 acres on one of the high points overlooking this sacred space (from the shore, you can see the Stars and Stripes peeking out high above, over the tree-line). Here, 9,387 Americans are buried, the vast majority of them casualties not only from Omaha Beach but throughout the Battle of Normandy which began on June 6 and went on until late August, when German forces retreated across the Seine. And not all D-Day casualties are buried there. After the war, families of deceased soldiers had the option to either have the bodies repatriated to the U.S. or buried in Europe. More than 60 percent chose to have the bodies shipped home. Still, the sight of nearly 10,000 graves is sobering, to say the least. As Reed writes, “The sheer scale of the American sacrifice is understood here, with crosses seemingly going on into infinity.”

Pyle moved along with the army. He joined forward units fighting in the hedgerows and ancient Norman towns, but also spent time with an antiaircraft battery protecting the newly secured invasion beaches and an ordinance repair unit. He would go on to witness the liberation of Paris. And in April, 1945, when Germany surrendered, the exhausted correspondent would agree to go cover the war in the Pacific, where American servicemen were eager to have him tell their stories, as well. On an island near Okinawa, in April, 1945, Pyle was killed by a Japanese sniper.

He is buried in Honolulu, but it could be argued that his spirit rests here with so many of the soldiers he wrote about on D Day.

As he finished his grim walk of Omaha Beach, Pyle noticed something in the sand. It inspired the poignant, almost poetic ending to his dispatch:

“The strong swirling tides of the Normandy coast line shifted the contours of the sandy beach as they moved in and out. They carried soldier’s bodies out to sea, and later they returned them. They covered the corpses of heroes with sand, and then in their whims they uncovered them.

As I plowed out over the wet sand, I walked around what seemed to be a couple of pieces of driftwood sticking out of the sand. But they weren’t driftwood. They were a soldier’s two feet. He was completely covered except for his feet; the toes of his GI shoes pointed towards the land he had come so far to see, and which he saw so briefly.”

I, too, have come far to see this place, albeit with the privileges and comforts of 21st century travel. As we head back to the car, I feel the warmth of the spring sun and a sense of unlimited space and possibility. Despite the gravity of what happened here 70 years ago, I feel like I could walk all day along this beach—and I have the freedom to do so. The men here gave their lives for that. Ernie Pyle told their stories, and died with them. It’s hard not to be humbled in their presence.

Editor's Note, June 6, 2013: This piece has been edited to correct the date of Ernie Pyle's death. He died in April, 1945, not August of that year. Thank you to commenter Kate for alerting us to the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ca/13/ca13798d-95d6-482f-b29f-b24c5c2debf3/42-28646879.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/b0/99b0a18b-aac3-49f6-b280-e240d0dccf8d/42-30873585.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c1/01/c101159d-2997-465d-b537-82432044b4a1/10732087665_ef39d35486_o.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/62/43/6243cf0c-052b-48ea-a76f-39f4d981b9b0/42-28646883.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/dd/e2/dde269f2-bfb0-4e32-bebd-d365050c379b/42-31334111.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f2/2f/f22fef60-4e66-44ea-b037-e37f41324e7a/15_d-day_42-16732151.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/37/99/3799ae51-f810-4a0c-9902-b68cb8856ff0/23_d-day_us002947.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/19/7e19e2de-3688-4b77-9d7b-18b8604c926a/21_d-day_na001170.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/ec/f0ece055-3959-48aa-9128-16af2ee89ece/20_d-day_us002967.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/08/f608d0ed-153a-407b-931c-499cee539ede/19_d-day_na007134.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a8/b5/a8b5c5fe-5eb1-4765-97a4-7fcc2d57facf/18_d-day_hu030895.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/3d/b63dacf3-3fa2-4faf-a0ca-15dc44895269/14_d-day_na008690.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/47/5247de2c-d4c8-4413-bba7-eb9af9f9ba7a/12_d-day_na012067.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cf/0f/cf0f7ce1-ea75-44bc-9b6a-1d4d6b06b3d4/10_d-day_0000295192-001.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7a/58/7a58b249-2ace-4f3e-bbcb-2f93ec700e54/02_d-day_42-21670573.jpg)