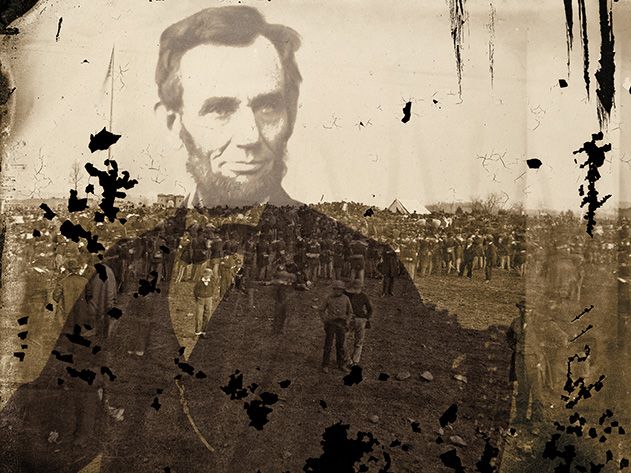

Will the Real Abraham Lincoln Please Stand Up?

A former Disney animator makes a provocative discovery by studying photos taken during the Gettysburg Address

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/the-new-lincoln-photo-631.jpg)

In Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film Blow-Up, a fashion photographer enlarges a series of pictures he’s taken and discovers he may have inadvertently witnessed a murder. His reconstruction of the event becomes an abstract study of subjectivity and perception. Does the camera ever lie? The question has profound implications for Christopher Oakley, who on March 5, during the bleak hours into the dawn, stumbled upon what looks to be the most significant, if not the most provocative, Abraham Lincoln photo find of the last 60 years. The former Disney animator savors the magic moment of discovery as if it were a Proustian madeleine or a 1943 Lincoln copper penny.

See Oakley's finding in this interactive photograph

Oakley, who teaches new media at the University of North Carolina-Asheville, was in his home studio working on a three-dimensional animation of Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg Address. Through the Virtual Lincoln Project, a collaboration with undergraduate researchers, Oakley hopes to shed more light on what happened during the historic dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, an event muddled by conflicting accounts, poor documentation, outright myths and a handful of confusing photographs.

Virtual Lincoln is both a marvel of computer Imagineering and an exercise in laborious exactitude. Over the last two years Oakley’s students have spent hundreds of hours perfecting Lincoln’s features circa November 1863, using Maya, a professional-grade animation and special-effects software program, and life casts Oakley has collected. Maya has also allowed the team to reconstruct the dedication sites of Evergreen and Soldiers’ National cemeteries as they looked at the time of Lincoln’s speech. Using the Evergreen gatehouse, a flagpole, stand-in models for the president and other notables, and four photos of the ceremony, the researchers have mapped out the various photographers’ positions and reproduced their images digitally. Their project is slated for completion by November 19, the 150th anniversary of Lincoln’s speech.

For verisimilitude, Oakley’s team mined the archives of the Library of Congress, which in 2002 began making its trove of more than 7,000 Civil War-era negatives available online in high-resolution scans. There are only about six-score-and-ten known photos of Lincoln, and the ones taken during his greatest rhetorical triumph are so rare that they’re viewed like holy relics. He’s been identified in only three shots, and two of those IDs—announced to great fanfare in 2007—have been challenged.

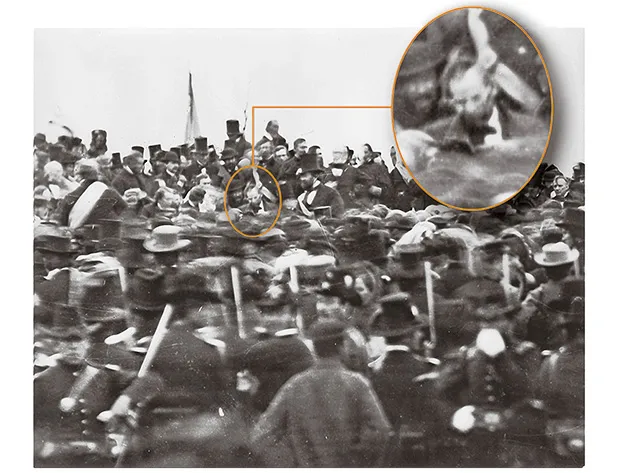

When Oakley made his breakthrough, he was studying an enlargement of one of the images in dispute, a wide crowd shot of the ceremony. To create it, the professional photographer Alexander Gardner had employed a new technique called the stereograph. Two lenses created photos simultaneously, which yielded a 3-D image when seen through a kind of early View-Master. The choicest stereograph views were mass-marketed to the public.

Oakley wanted his animated 3-D re-creation of Gettysburg to feature a Sgt. Pepper-esque collage of the dignitaries who were seated with Lincoln on the platform. While trying to distinguish them in the right half of Gardner’s first stereo plate, he zoomed in and spotted, in a gray blur, the distinctive hawk-like profile of William H. Steward, Lincoln’s secretary of state. Oakley superimposed a well-known portrait of Seward over the face and toggled it up and down for comparison. “Everything lined up beautifully,” he recalls. “I knew from the one irrefutable photo of Lincoln at Gettysburg that Seward sat near him on the platform.” He figured the president must be in the vicinity.

Oakley downloaded the right side of a follow-up shot Gardner snapped from the same elevated spot, but the image was partly obscured by varnish flaking off the back of the 4- by 10-inch glass-plate negative. “Still, Seward hadn’t budged,” he says. “Though his head was turned slightly away from camera, he was in perfect profile.” To Seward’s left was the vague outline of a bearded figure in a stovepipe hat. Oakley leaned into the flat-screen monitor and murmured, “No way!” Zooming in tight, real tight, he stared, compared and sprang abruptly from his chair. After quickstepping around his studio in disbelief, he exulted, “That’s him!”

SEE AN INTERACTIVE DISPLAY OF OAKLEY'S FINDINGS

***

Oakley pulls together information the way a field marshal gathers an army. What separates him from other Abe-olitionists is his animator’s eye—he’s been trained to track and recreate movement and understand how it works.

“I became a Lincoln freak at age 5,” he says. He still remembers the Great Emancipator’s stern visage looming above him on a kindergarten wall in Crystal Lake, Illinois. “I know this sounds silly,” says the 51-year-old professor, “but when I saw that picture, I felt like I knew him and that he was a nice man.”

Oakley is a genial fellow, too. His outlook on life is sardonic and amused, and his home is a sometimes-whimsical testament to his fascination with the nice man in the picture. Amid the sculptures, sketches and paintings of Lincoln are dozens of books, medallions, life casts of his face and hands, and a CD of Oakley’s very first high-school animation—a stop-motion re-enactment of Lincoln’s assassination. (The Super 8 film starred G.I. Joe as Lincoln; a Kewpie-like doll as his wife, Mary; and the Lone Ranger as John Wilkes Booth.) In storage are two boxes of figurines he made in college during an abortive stab at a clay-animated Gettysburg Address, the spiritual forefather of Virtual Lincoln.

During the early 1980s, shortly before he began cranking out cartoons for “Pee-wee’s Playhouse,” Oakley bought a book about Gettysburg that featured a David Bachrach photo of a dense throng of soldiers. In 1952, Josephine Cobb, then the chief of the Still Photo Section of the National Archives, hunted in the background and—focusing on a slight rise that suggested where the stage was—spied the hatless Lincoln. For more than a half century, that was believed to be the lone image of Lincoln at Gettysburg.

Six years ago, a Civil War hobbyist named John Richter magnified the first Gardner stereograph enough to pick out, deep in the crowd, a man on horseback amid what appeared to be a military procession. Too tiny to see with the naked eye, the tall, slim rider sported a bushy beard and a top hat. His white-gloved left hand was raised to his forehead in apparent salute.

A close-up view of the right portion of Gardner’s follow-up photo revealed that the horseman had lowered his hand. In both shots, the man’s back was to the camera. Though neither offered a clear view of his face, the more Richter stared at the enhanced 3-D images on his screen, the more certain he was that he had something special.

Richter is a director of the Center for Civil War Photography, a Web-based community of self-made experts. The core members compose a kind of murder board for anyone who thinks he has a new finding. The murder board is as hard to please as Madonna, for whom Oakley once created a backdrop video she used on tour. “These guys are approached all the time by people who literally see Jesus in a piece of toast,” Oakley says.

In Richter’s case, the center’s president, Bob Zeller, was dead certain that the figure was the president on his way to the stage. Zeller reasoned that Lincoln rode on horseback to the ceremony while wearing a top hat and white riding gloves. Gardner, he deduced, had taken rapid-fire photos of the faraway president. Or rapid-ish, considering that the shots may have been taken as much as ten minutes apart. “I’m absolutely convinced,” said Zeller, who later teamed up with Richter to write the book Lincoln in 3-D.

The discovery of possible Lincoln photos made national news. The claim was endorsed by no less an eminence than Harold Holzer, chairman of the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation.

Not everyone on the murder board was swayed by Richter and Zeller’s conclusions, however. The center’s vice president, Garry Adelman, had serious misgivings. But none of the heavy hitters on Murderers’ Row was more skeptical than William Frassanito, the Gettysburg photo pioneer whose sleuthing had shown that one of Gardner’s iconic battleground shots was staged.

***

It’s round midnight at the Reliance Mine Saloon, and Fraz, as he is known, is nursing his third Coors Light of the evening. He rose, as he does every day, at 4 p.m., and entered this cavelike Gettysburg tavern at 10:30 on the nose, as he does every Monday, Wednesday and Friday.

Bellied up to the bar, stroking his whiskers, Fraz looks like a worn and weathered Walt Whitman pondering the silence. He shifts a little creakily on his stool—he’s 67 now—and begins to tick off reasons Richter’s Lincoln is not Lincoln. Carefully, cheerfully, he says: “For starters, the guy on the horse looks like a Cossack. His beard is longer and much fuller than the wispy, trimmed one the president wore in his studio session with Gardner 11 days before. Lincoln had an unmistakable gap between his goatee and his sideburns. If you’re going to spy him in a black speck in a distant background, at least get the beard right.”

For his part, Oakley never bought into Richter’s Lincoln, either. He chuckles at the idea that Gardner was a long-range paparazzo. He maintains that the photographer was taking “establishing shots” that showed the pageantry of the procession and the breadth of the gathered crowd. “Gardner was well used to photographing the president and wouldn’t have been overly excited by a distant view of him that he knew would be difficult to see and market,” he says. “If Gardner did manage to capture an image of Lincoln, either on a horse or on foot, it most likely was by accident.”

After unearthing his own accidental Lincoln in the second Gardner stereograph, Oakley wrote to the Library of Congress and asked if the left-side negative of that view had ever been scanned. It hadn’t, so Oakley ordered a copy. Curiously, Richter and Zeller had been requesting the very same scan for years, to no avail.

As it turned out, the left half was in better shape than the right, but Oakley’s Lincoln looked fuzzy even when blown up. Oakley knew that Gardner, in the studio session, had taken a profile portrait of Lincoln facing left, just like the possible Lincoln he was now looking at. The Gardner profile would offer the most accurate representation of Lincoln’s hair and beard as they were on dedication day, so Oakley downloaded a high-resolution scan of it from the Library of Congress website and used Photoshop to cut out a separate image of the face. He then overlaid that face on the figure in the second stereograph, sizing it to the same scale and rotating it to look downward, just as the man in the stereograph photo is doing.

“All the landmarks—jaw line, beard, hair, cheekbones, heavy brow, ears, line up perfectly,” Oakley says. Most astonishingly, when his researchers triangulated the location of the speakers’ stand from four photos of the ceremony, his Lincoln appeared in precisely the right spot.

One thing mystified Oakley, however. Why was his Lincoln on Seward’s left when eyewitness accounts and the Bachrach photo have him seated on Seward’s right? The answer, Oakley says, became clear when his team got its 3-D model together and synced the virtual cameras with the actual photos. The stand, they concluded, was three feet off the ground, and the 6-foot-4 Lincoln was not seated on it, but standing in front of it.

The new scan also revealed what Oakley calls the “most damning evidence” against Richter’s man on the horse being Lincoln. The figure appears to have epaulets on his shoulders that were not visible in previous iterations. “If those are indeed epaulets,” says Oakley, “the man is in uniform, despite the top hat, and cannot be Lincoln.”

Armed with his findings, Oakley sought audiences with the murder board’s Murderers’ Row. Of course, Lincoln could not have appeared in two different places in the same photograph, so he and Richter couldn’t both be right. Opinion was deeply divided and, with some members, perhaps not unbiased. Richter and Zeller were impressed by Oakley’s technological wizardry, but unmoved by his inferences. “It’s like looking at an ink blot,” says Richter. “If you want to see a butterfly, you can see a butterfly. Personally, I don’t see Lincoln.”

Garry Adelman is not so dismissive. “I have never been a big proponent of John’s Lincoln theory,” he says. “I feel considerably better about Christopher’s ID.” Harold Holzer went farther, disowning Richter’s speck and embracing Oakley’s ink blot as “convincing,” even if not “beyond dispute.” “Pretty amazing,” he says. “It’s like ‘Law & Order’: You keep enhancing an image until you see the suspect.”

You can count Fraz in the Oakley camp. “My sense is that Chris has found Lincoln on the platform,” he says. “The resemblance is 80 percent in favor.” His only question: Why is Lincoln standing below the platform when all the other dignitaries are seated? Oakley’s answer: Now that the crowd has been safely pushed back, Lincoln is preparing to mount the steps.

The implications of Oakley’s detective work do not sit particularly well with Richter and Zeller. Told that Fraz backs the ink blot, Richter’s voice suddenly jumps an octave. “The man I found had to be Lincoln,” he says. “Who else might have been returning a salute but the commander in chief?” Well, pretty much anyone but Lincoln. It’s generally accepted that Ronald Reagan was the first president to salute the troops—Dutch caused a big ruckus in 1981 when he broke ranks on tradition to do so. Lincoln’s response to salutes from the military has been documented. He simply tipped his hat.

So who was Richter’s Lincoln? Fraz has an idea. Hundreds of members of the Independent Order of Odd Fellows attended the dedication. Fraz owns the logs of the Gettysburg lodge from 1846 to 1885. “The fraternal order assigned its own marshals to the ceremony,” he says. “No one knows what their uniforms looked like.” He’s betting Horseback Man was an Odd Fellows official or some other marshal.

Zeller, the most ardent defender of John Richter’s Lincoln, accuses Fraz of being disingenuous. “In my opinion, Bill sees this discovery, if considered legitimate and real, as something that he missed, but that he should not have missed. As such, it would be a threat to his legacy and his work in historic photography at Gettysburg. If he was to acknowledge John’s Lincoln as Lincoln, it would mean that he would have to acknowledge the existence of something significant in the photo that he himself overlooked.”

No one has ever questioned Fraz’s integrity before—at least not publicly—and this personal attack from a one-time protégé clearly disappointed him. History, he says, is like a vast puzzle for which most of the pieces will forever remain missing. “The historian’s job is to gather as many pieces as he can from as many sources as possible,” he says. “You come up with as logical an interpretation as you can, always realizing that new pieces will surface indefinitely.” To his mind, Oakley is laying a foundation for future scholars to work with.

We may never know if Oakley’s Honest Abe is Honest-to-Goodness Abe. “All I can say is I’ve sculpted Lincoln, sketched him, painted him and animated him getting shot,” he says. “I’ve been looking at his face for nearly 50 years, and last March, at 3 a.m. in my studio, he looked back.