William Shakespeare, Gangster

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20111107105016Chandos-portrait-william-shakespeare.jpg)

You wouldn’t think it by looking at the long line of Shakespeare biographies on the library shelves, but everything we know for sure about the life of the world’s most revered playwright would fit comfortably on a few pages.

Yes, we know that a man named Will Shakespeare was born in the Warwickshire town of Stratford-upon-Avon in 1564. We know that someone of pretty much the same name married and had children there (the baptismal register says Shaxpere, the marriage bond Shagspere), that he went to London, was an actor. We know that some of the most wonderful plays ever written were published under this man’s name–though we also know so little about his education, experiences and influences that an entire literary industry exists to prove that Shaxpere-Shagspere did not write, could not have written, them. We know that our Shakespeare gave evidence in a single obscure court case, signed a couple of documents, went home to Stratford, made a will and died in 1616.

And that’s just about it.

In one sense, this is not especially surprising. We know as much about Shakespeare as we know about most of his contemporaries–Ben Jonson, for instance, remains such a cipher that we can’t be sure where he was born, to whom, or even exactly when. “The documentation for William Shakespeare is exactly what you would expect of a person of his position at that time,” says David Thomas of Britain’s National Archives. “It seems like a dearth only because we are so intensely interested in him.”

John Aubrey, the collector of many of the earliest anecdotes regarding Shakespeare. Illustration: Wikicommons.

To make matters worse, what does survive tends to be either evidence of dubious quality or material of the driest sort imaginable: fragments from legal records, mostly. The former category includes most of what we think we know about Shakespeare’s character; yet, with the exception of a couple of friends from the theatrical world who made brief mention of him around the time he died, most of the anecdotes that appear in Shakespeare biographies were not collected until decades, and sometimes centuries, after his death. John Aubrey, the noted antiquary and diarist, was among the first of these chroniclers, writing that the playwright’s father was a butcher, and that Shakespeare himself was “a handsome, well shap’t man: very good company, and of a very redie and pleasant smoothe Witt.” He was followed a few years later by the Reverend Richard Davies, who in the 1680s first wrote down the famous anecdote about Shakespeare’s leaving Stratford for London after being caught poaching deer on the lands of Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote Park. Yet the sources of both men’s information remain obscure, and Aubrey, in particular, is known for writing down any bit of gossip that came to him.

There is not the least shred of evidence that anybody, in the early years of the Shakespeare cult, bothered to travel to Warwickshire to interview those in Stratford who had known the playwright, even though Shakespeare’s daughter Judith did not die until 1662 and his granddaughter was still alive in 1670. The information that we do have lacks credibility, and some of it appears to be untrue; the most recent research suggests that Shakespeare’s father was a wool merchant, not a butcher. He was wealthy enough to have been accused of usury–the loan of money at interest, forbidden to Christians–in 1570.

Absent firsthand information about Shakespeare’s life, the only real hope of finding out much more about him lies in making meticulous searches through the surviving records of late Elizabethan and early Jacobean England. The British National Archives contains tons of ancient public records, ranging from tax records to writs, but this material is written in cramped, jargon-ridden and abbreviated dog Latin that cannot be deciphered without lengthy training. Only a very few scholars have been willing to devote years of their lives to the potentially fruitless pursuit of Shakespeare’s name through this endless word-mine, and the lack of firm information about Shakespeare’s life has had important consequences, not least for those who attempt to write it. As Bill Bryson puts it:

With so little to go on in the way of hard facts, students of Shakespeare’s life are left with essentially three possibilities: to pick minutely over…hundreds of thousands of records, without indexes or cross references, each potentially involving any of 200,000 citizens, Shakespeare’s name, if it appears at all, might be spelled in 80 different ways, or blotted or abbreviated beyond recognition…to speculate…or to persuade themselves that they know more than they actually do. Even the most careful biographers sometimes take a supposition–that Shakespeare was Catholic or happily married or fond of the countryside or kindly disposed towards animals–and convert it within a page or two to something like a certainty. The urge to switch from the subjunctive to the indicative is… always a powerful one.

Bryson is, of course, quite right; most Shakespeare biographies are highly speculative. But this only makes it all the more remarkable that scholars of Shakespeare have chosen to pretty much ignore one of the very few new documents to emerge from the National Archives over the last century. It is an obscure legal paper, unearthed from a set of ancient sheets of vellum known as “sureties of the peace”, and it not only names Shakespeare but lists a number of his close associates. The document portrays the “gentle Shakespeare” that we met in high school English class as a dangerous thug; indeed, it has been plausibly suggested that it proves he was heavily involved in organized crime.

Exploring this unlighted lane in Shakespeare’s life means, first, looking at the crucial document. “Be it known,” the Latin text begins,

The 1596 writ charging Shakespeare with making death threats, discovered in Britain's National Archives by the Canadian scholar Leslie Hotson in 1931. The second of the four entries is the one relating to the playwright.

that William Wayte craves sureties of the peace against William Shakspere, Francis Langley, Dorothy Soer wife of John Soer, and Anne Lee, for fear of death, and so forth. Writ of attachment issued by the sheriff of Surrey, returnable on the eighteenth of St Martin .

A few pages away in the same collection of documents, there is a second writ, issued by Francis Langley and making similar charges against William Wayte.

Who are these people, each alleging the other was issuing death threats? The scholar who unearthed the document—an indefatigable Canadian by the name of Leslie Hotson, best remembered today as the man who first stumbled across the records of the inquest into the highly mysterious murder of Shakespeare’s fellow playwright, Christopher Marlowe—uncovered a squalid tale of gangland rivalries in the theatrical underworld of Queen Elizabeth’s day.

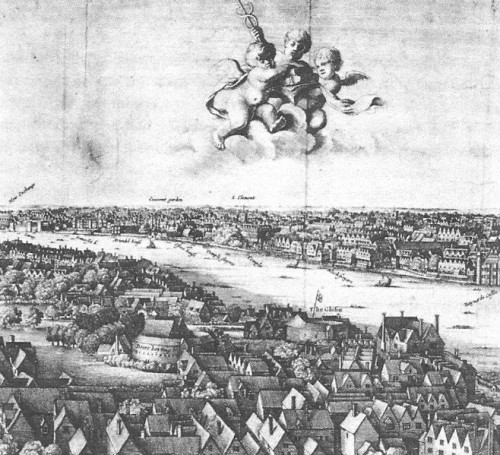

According to Hotson’s researches, Shakespeare was an energetic, quick-witted but only sketchily educated country boy—perfect qualifications for someone trying to make his way in the bohemian and morally dubious world of the theater. That world was far from respectable in those days; that is why London’s playhouses were clustered on the south bank of the Thames, in the borough of Southwark, outside the jurisdiction of the City of London–and why the document Hotson discovered lies with the Surrey writs and not among those dealing with London proper.

The shady pleasure districts of Southwark in Shakespeare's time—safely on the far side of the river from the forces of law and order.

As a newcomer to the big city, Hotson realized, Shakespeare was obliged to begin his career on a lowly rung, working for disreputable theater people—which, at that time, was generally regarded as akin to working in a brothel. Theaters were meeting places for people whose interest in the opposite sex did not extend to marriage; they were also infested with crooks, pimps and prostitutes, and attracted an audience whose interest in the performance on stage was often minimal. This, of course, explains why the Puritans were so quick to ban public entertainments when they got the chance.

What seems certain is that the work that the young Shakespeare found took him to the shadiest part of the theater world. Most biographers suggest his first employer was Philip Henslowe, who became wealthy as much from his work as a brothel landlord as he did as a theatrical impresario. Nor was the playwright’s next boss, Langley, much of a step up.

Langley, as Hotson’s minutely careful research shows, had made much of his fortune by crooked means, and was the subject of a lengthy charge sheet that included allegations of violence and extortion. He was the owner of the newly constructed Swan Theater, which the Lord Mayor of London had campaigned against, fruitlessly, on the ground that it would be a meeting spot for “thieves, horse-stealers, whoremongers, cozeners, connycatching persons, practisers of treason, and such other like”–a formidable list, if you know that “cozeners” were petty confidence men and “connycatchers” were card sharps.

Langley’s most dangerous opponent was William Wayte, the man who accused Shakespeare of threatening him. Wayte was noted as the violent henchman of his stepfather, William Gardiner, a Surrey magistrate whom Hotson was able to show was highly corrupt. Gardiner made a living as a leather merchant in the upmarket district of Bermondsey, but most of his money came from criminal dealings. Legal records show that several members of his wife’s family sued him for swindling them; at different times he was found guilty of slander and “insulting and violent behaviour,” and he served a brief prison sentence for the latter. Gardiner’s appointment as a magistrate indicates no probity, merely the financial resources to make good any sums due to the crown in the event that some prisoner defaulted on them. Since they took this risk, most magistrates were not above exploiting their post to enriching themselves.

Biographers who have made mention of the writ’s discovery since Hotson made it in 1931 have tended to dismiss it. Shakespeare must simply have got caught up in some quarrel as a friend of Langley’s, they suggest–on very little evidence, but with the certainty that the author of Hamlet could never have been some sort of criminal. Thus the evidence of the sureties, Bill Bryson proposes, is “entirely puzzling,” while for the great biographer Samuel Schoenbaum, the most plausible explanation is that Shakespeare was an innocent witness to other men’s quarrels.

A contemporary depiction of the Globe Theatre, part-owned by Shakespeare and built on much the same model as Francis Langley's Swan.

This seems almost willful distortion of the evidence, which seems fairly unambiguously to show that the playwright—who is named first in the writ–was directly involved in the dispute. Indeed, Hotson’s researches tend to suggest that Langley and Gardiner were in more or less open conflict with each other for the spoils of the various rackets that theater owners dabbled in—that their dispute was, in John Michell’s phrase, “the usual one between urban gangsters, that is, control of the local vice trade and organized crime.” And since Shakespeare “was principal in their quarrel,” Michell reasonably concludes, “presumably he was involved in their rackets.”

Certainly, Will’s other associates seem to have been no more salubrious that Langley and Gardiner. Wayte was described in another legal case as a “loose person of no reckoning or value.” And though Hotson could discover nothing definite about Soer and Lee, the two women in the case, he plainly suspected that they were associated with Langley through his extensive interests in the Southwark brothel business. Shakespeare, meanwhile, was perhaps the man who supplied Langley with muscle, just as Wayte did for Gardiner. As much is suggested by one of the four principal portraits supposed to show him: the controversial “Chandos portrait” once owned by the Duke of Buckingham. As Bill Bryson points out, this canvas seems to depict a man far from the diffident and balding literary figure portrayed by other artists. The man in the Chandos portrait disturbed Schoenbaum, who commented on his “wanton air” and “lubricious lips.” He “was not, you sense,” Bryson suggests, “a man to whom you would lightly entrust a wife or grown daughter.”

There is plenty of evidence elsewhere that Shakespeare was somewhat less than a sensitive poet and entirely honest citizen. Legal records show that him dodging from rented room to rented room while defaulting on a few shillings’ worth of tax payments in 1596, 1598 and 1599—though why he went to so much trouble remains obscure, since the totals demanded were tiny compared to the sums that other records suggest he was spending on property at the same time. He also sued at least three men for equally insignificant sums. Nor was Will’s reputation among other literary men too good; when a rival playwright, Robert Greene, was on his deathbed, he condemned Shakespeare for having “purloined his plumes”—that is, cheated him out of his literary property—and warned others not to fall into the hands of this “upstart crow.”

That Will Shakespeare was somehow involved in the low-life rackets of Southwark seems, from Hotson’s evidence, reasonably certain. Whether he remained involved in them past 1597, though, it is impossible to say. He certainly combined his activities as one of Langley’s henchmen with the gentler work of writing plays, and by 1597 was able to spend £60—a large sum for the day—on purchasing the New Place, Stratford, a mansion with extensive gardens that was the second-largest house in his home town. It is tempting to speculate, however, whether the profits that paid for such an opulent residence came from Will’s writing–or from a sideline as strong-arm man to an extortionist.

Sources

Brian Bouchard. “William Gardiner.” Epson & Ewell History Explorer. Accessed August 20, 2011. Bill Bryson. Shakespeare: the World as a Stage. London: Harper Perennial, 2007; Leslie Hotson. Shakespeare Versus Shallow. London: The Nonesuch Press, 1931; William Ingram. A London Life in the Brazen Age: Francis Langley, 1548-1602. Cambridge : Harvard University Press, 1978; John Michell. Who Wrote Shakespeare? London: Thames & Hudson, 1996; Oliver Hood Phillips. Shakespeare and the Lawyers. Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge, 1972; Ian Wilson. Shakespeare: The Evidence. Unlocking the Mysteries of the Man and His Work. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1999.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mike-dash-240.jpg)