The war couldn’t last much longer. Any day now a cheer would sweep across the airfield. No more missions, no more dice rolls, no more terror in the sky.

A map in the Officer’s Club showed the advancing front lines, with Germany nearly pinched in half as the Americans and British pushed in from the west and the Russians squeezed from the east. Bombers had already destroyed much of military value to the Germans and flattened wide swaths of several cities. But still the Germans fought on.

At 2 a.m. on April 25, 1945, an orderly woke Second Lt. William Hesley and told him to get ready to fly. Hesley had joined the war late, just four months earlier, but 24 times already he had choked down an early-morning breakfast at Podington Air Base, north of London, and crowded into the briefing room, waiting for his fate to be revealed.

An intelligence officer slid the curtain aside, from left to right across the map, farther and farther, all the way beyond Germany to their target in western Czechoslovakia. Once over the city of Pilsen, the B-17 Flying Fortress crews would drop their 6,000-pound payloads onto Skoda Works, a massive 400-acre factory complex that had armed the Austro-Hungarian Empire in World War I. Ever since the Nazis had taken over Czechoslovakia in 1939, more than 40,000 Czech civilian workers there had built tanks and cannons, machine guns and ammunition for the Germans. Allied bombers had tried several times to destroy it, without success.

In the spring of 1945, the Americans and Brits had another motive for destroying the factory: Once the war was over, they didn’t want the Russians to dismantle the factory for industrial production at home, which made the mission one of the earliest chess moves of the Cold War.

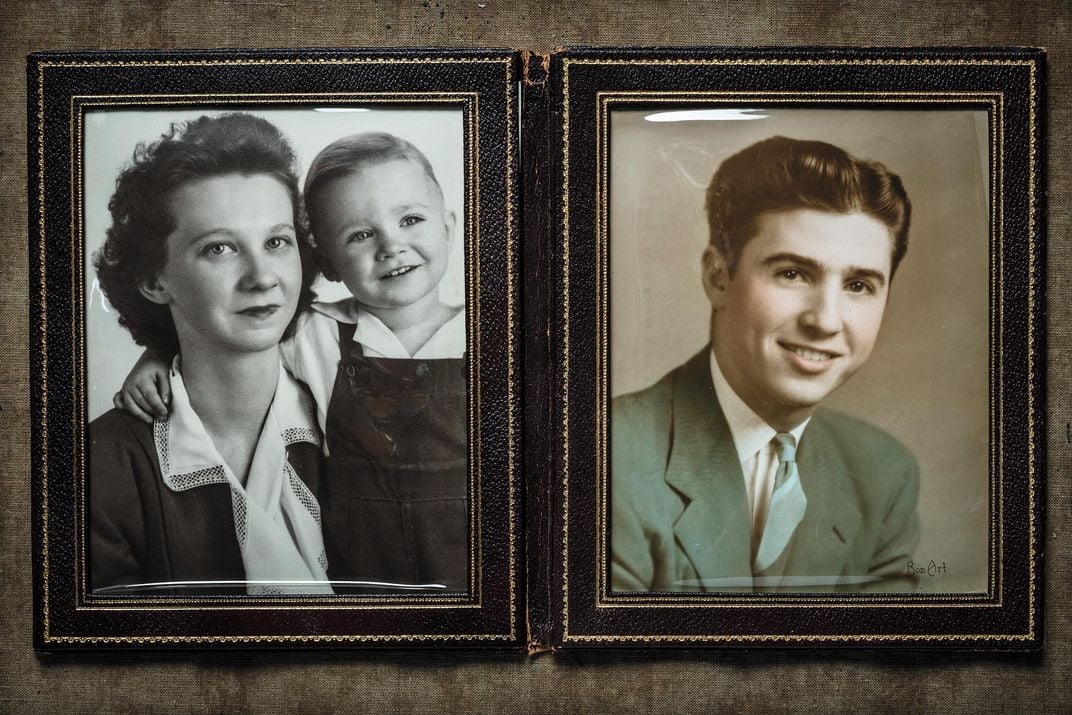

On the flightline, Hesley hoisted himself into a B-17 named Checkerboard Fort. He settled into the navigator’s station at a tiny desk beneath the cockpit and just behind the bombardier’s position in the plane’s plexiglass nose. He had never flown with this crew before. Indeed, Hesley, who had turned 24 three days earlier, hadn’t been scheduled to fly this day, but had volunteered to take the place of a sick navigator. This mission happened to fall on his third wedding anniversary; with a little luck, he’d soon be home in Paris, Texas, where Maribelle waited with their 2-year-old boy, John.

The pilot, First Lt. Lewis Fisher, gunned the four massive engines. The bomb-laden plane lifted off the runway and the English countryside faded beneath them. Fisher slid into a miles-long formation of 296 B-17s and crossed the English Channel. Hesley spread out his maps and charts and busied himself with calculations for what would be the Eighth Air Forces’ last bombing mission of World War II.

Their orders for Pilsen were for visual bombing only, which meant the bombardiers had to see the target clearly. The alternative is area bombing—close enough is good enough. Bombing industrial targets in Germany, the Allies weren’t as concerned about whether their bombs fell into neighborhoods. The British frequently hit civilian areas to break the German will to fight, and as the war dragged on the Americans broadened their targets as well. But the Czechs were not the enemy, and killing thousands of them could only sow ill will and slow their recovery from years of war and occupation. Better to risk few and save many.

Some of the bomber radio operators tuned into the BBC broadcast to break the monotony of another long flight and to keep their minds off the artillery shells that would soon splinter the sky, the shards of shrapnel that might rip through their planes’ thin aluminum skins. Far from calming their nerves, what they heard chilled them. “Allied bombers are out in great strength today. Their destination may be the Skoda Works,” an announcer said, the first time in the war the Allies had issued a warning before a major bombardment. “Skoda workers get out and stay out until the afternoon.”

The warning would likely save thousands of civilians, but it also told the Germans where to concentrate their defenses. For the aircrews rumbling toward Pilsen, their chances of surviving this last mission just took a serious hit.

* * *

War has been fought on land and at sea for millennia, but World War II brought it fully into the skies with strategic bombing, meant to destroy a country’s economy and infrastructure and crush its people’s will to fight.

The British, who favored nighttime bombing, couldn’t accurately hit precise targets in the dark. Instead, they blanketed German cities with bombs, as the Germans had done to them. But with the high-tech Norden bombsight, the Americans were sure they could knock out specific targets, like armament factories and railroad yards—and do it without fighter escorts.

Though the B-17 bristled with a dozen or more .50-caliber machine guns from nose to tail, proponents of unescorted daylight bombing overestimated the plane’s ability to defend against the German fighters, which darted through formations and tore into the bombers.

On an October 1943 mission to destroy several ball-bearing plants in Germany, 60 B-17s were shot down, which left 564 empty bunks that night at air bases across England. That same week in a raid over Munster, the 100th Bomb Group, nicknamed “The Bloody Hundredth,” lost 12 of 13 bombers.

And the losses kept piling up. During the air war over Europe, the Eighth Air Force would suffer more than 26,000 men killed in action—more than all the U.S. Marines killed in the South Pacific. Still, Hesley figured it better than the alternative. “If I have to die,” he told Maribelle, “better up here in the air than down in the mud.”

Before leaving for England in late 1944, he wrote a letter for her to read to John on his second birthday, the following April. It was the sort of letter meant to be read through the years, full of expressions of love and pride, and hopes for the man his son would become. “In case anything should ever happen to daddy either now or later on in life,” he wrote. “I want you to always take care of your mother for me.”

But he reassured his son that he’d be home soon, that everything would be fine, something a little boy could understand.

“Saying goodbye to you was the hardest thing I think that your Daddy ever had to do,” Maribelle wrote in a letter for John’s 21st birthday. “Because in his heart he knew it would be the last time he would ever be with his son on earth.”

“After he left, you and I pretended he was there living with us. It was the best way I knew to get you ‘acquainted’ with him while he was gone. Because I knew that he would be back, just as strongly as he knew that he would not.”

* * *

Maribelle first saw William at a dance at the Gordon Country Club in 1941. She was home on spring break from Texas Christian University. He worked as the night manager at a hamburger joint called Green Castle. She told her friend Jeanne that was the man she would marry, never mind that she hadn’t met him yet.

They married the next spring. He enlisted in the Army a few months later and volunteered for flight school. After his initial single-engine pilot training, he was assigned to be a navigator. Not as glamorous as being the pilot, this was the toughest job on the plane, getting the crew to the target and then back home. Hesley had to know the plane’s exact location at any moment, through tracking airspeed and direction, noting terrain features on the ground, triangulating radio signals and even using the stars by looking through a plexiglass bubble above the navigator’s desk.

The conditions were miserable. The plane flew at about 25,000 feet, and wasn’t pressurized or heated. Oxygen masks often clogged with ice, and exposed skin could freeze in minutes.

By the time Hesley came to the war, in January of 1945, the Luftwaffe wasn’t nearly the threat it had been, crippled by fuel shortages, a lack of experienced pilots and relentless attack by the Allies. The introduction in late 1943 of the P-51B Mustang, a fighter capable of escorting the bombers deep into Germany and back, had greatly reduced the effectiveness of the Luftwaffe. But the antiaircraft guns remained just as dangerous as ever.

The Germans tracked the incoming bombers with radar and fired ahead of the planes, the way a hunter leads a flying duck with a shotgun. To counter this, the formations changed course frequently as they flew over enemy territory, forcing the Germans to constantly change their firing coordinates. This kept Hesley and the other navigators busy, plotting flight adjustments that zigzagged them toward the targets.

Once the bombers were over the target area they couldn’t change course, and the Germans could throw up a barrage of shells, creating an enormous aerial box of shrapnel. The air crews could do little but hope that a shell wouldn’t find them, and that their flak jackets and steel helmets would protect them from the shards of metal. The Flying Fortress was tough, able to fly with two and even three engines out. They regularly returned to England peppered with holes, and sometimes with whole chunks of plane shot away. But many erupted into fireballs or spiraled down, out of control, as men in other planes watched and waited for little white flashes of parachutes.

Even without enemy fighters and flak, just getting to and from the target was incredibly dangerous. Flying over Dresden, Germany, on April 17 to bomb railroad tracks and marshaling yards, the lead squadron lost its way in the clouds and flew into the path of another group of bombers. Pilots realized the mistake too late. Queen of the Skies and Naughty Nancy, flown by Lt. John Paul, slammed together and plummeted to the ground.

Hesley had trained with Paul and his crew in America and flown with them for the first several weeks. He’d recently started filling in as navigator on different crews, so he wasn’t with them that day. More dead friends and empty bunks, and no time to mourn. The next morning Hesley was over southern Germany bombing rail yards near Munich.

For the next week, with the Allies advancing so rapidly toward Berlin, hopes rose among the aircrews that they had flown their last mission. But the Skoda Works waited for them.

The complex supplied the Germans with everything from bullets and tanks to plane engines and the 88-millimeter cannons that devastated the bomber formations. The Skoda Works was so important to the Germans that they built a wood and canvas replica of the factory several miles away to confuse the Allies, who had tried several times to destroy the factory. In April of 1943, the British Royal Air Force sent more than 300 heavy bombers to Skoda, but mistakenly bombed a psychiatric hospital in the nearby town of Dobrany—and lost 36 planes.

April 25 was supposed to be a bluebird day, perfect bombing weather. The scout planes reported clear skies, but they had gotten lost and were reporting the weather over Prague. When the formation arrived over Pilsen in the late morning, they found the city clouded over.

The Germans couldn’t see the bombers, but they could hear them and watch them on radar. They fired barrages of shells that pockmarked the sky with ragged black puffs of smoke and showers of shrapnel.

The bombers started their run toward the Skoda Works, hoping the clouds might part, just for a quick moment. No luck.

Bombardiers eased their fingers from the release toggles and pilots made the stomach-churning announcement to their crews: We’re going around again.

* * *

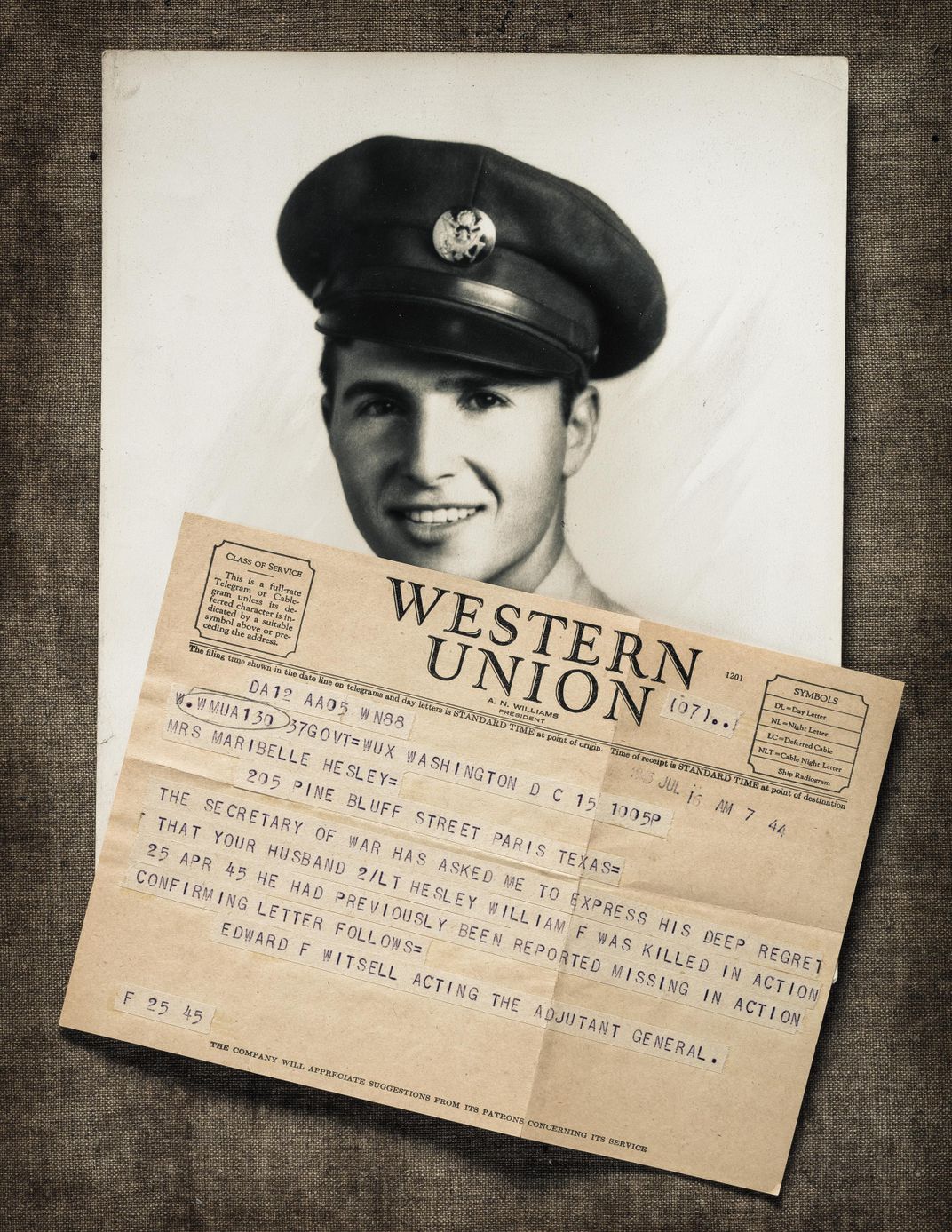

The war in Europe ended on May 8 and Maribelle received the telegram on May 11. “The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your husband 2/LT Hesley William has been missing in action over Czechoslovakia since 25 April 45.”

Maybe he’d bailed out and been taken prisoner. She kept the same routine she started after William left, setting a place for him at the table, even after she received another telegram, on July 16, confirming that he’d been killed in action.

When John was 3 years old he asked her when his daddy was coming home. His first memory is his mother’s answer. He ran to a bedroom closet with a window where he sometimes played. He looked out on the sun shining through the trees and he wept.

John knew plenty of kids whose dads fought in the war. But their dads had all come home. His mother, mired in her own grief, kept the blinds drawn, the house dark, and he often escaped to his grandparents’ home next door.

Three years after John’s father died, Maribelle remarried. But his stepfather, who had served in Europe with the Army, had his own struggles. Each night he’d walk into the fields near their farmhouse with a bottle of Old Crow whiskey, coming home when he’d drunk enough to sleep through the night.

She married again, in John’s late teens, to a Marine who saw brutal combat in the South Pacific and talked about having to burn Japanese soldiers out of caves with a flamethrower. Between the ghost of William and two more damaged husbands, the war never let go of her—or John.

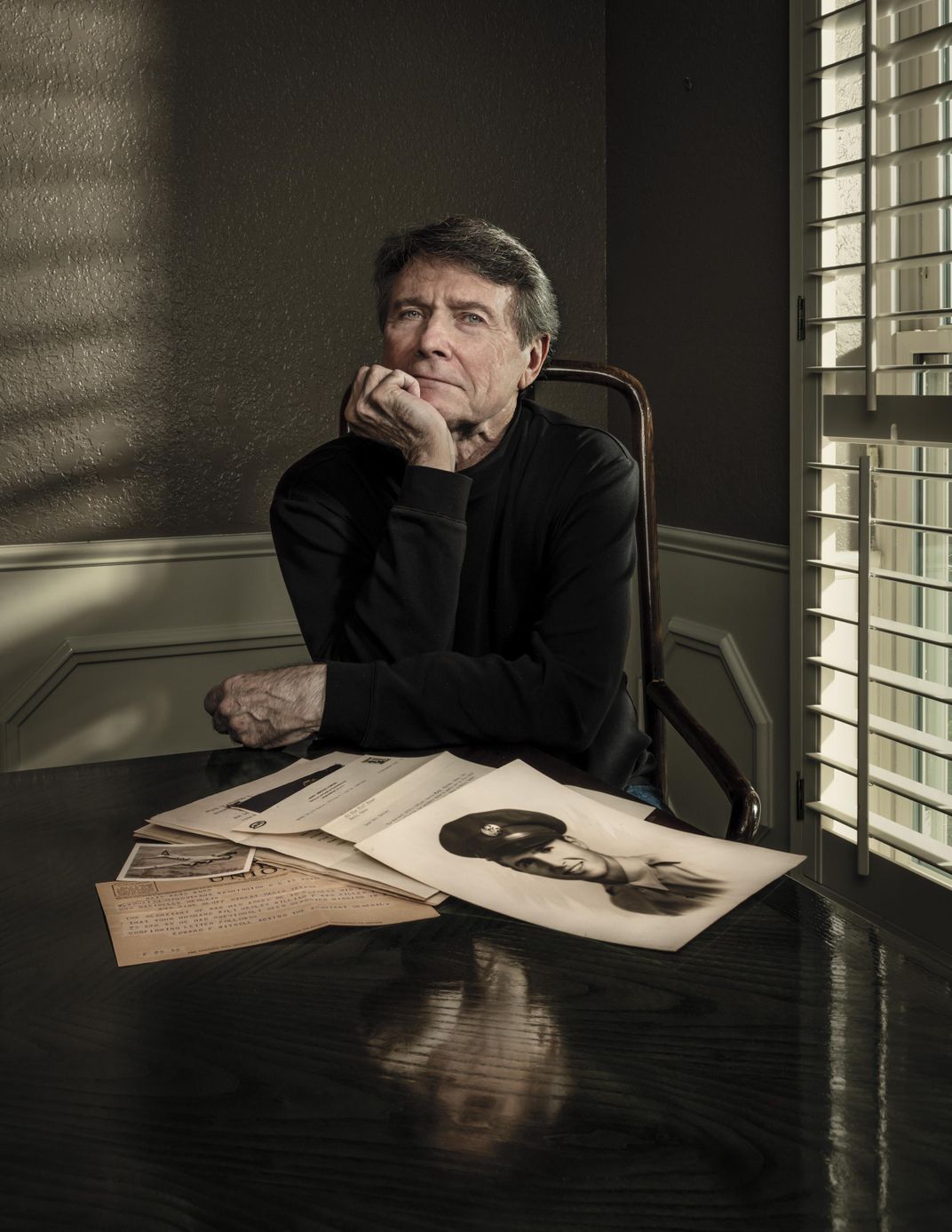

“Up until she died, he was the only love of her life, which is hell on a kid,” John says of his father, sitting in the book-lined study of his home in Arlington, Texas, where he lives with his wife, Jan. He has a lean runner’s build, silver-streaked hair and a smile that starts at the eyes. He speaks slowly and softly, his voice tinged by a lifetime of Texas living. “You’re growing up and he’s perfect,” he says. “You can never be perfect.”

John played football, even though he was small, to feel like less of an outsider, to show the other kids he could be just like them, even without a father. He earned starring roles in school plays and was elected class president, several years running.

Yet he felt his own time was running out. He had convinced himself that he would die young. As his family’s sole surviving son, he was exempt from service in Vietnam, but in college he passed the test to start naval flight training. Since his father died in a plane in combat, maybe that should be his fate, too.

But before he signed the final papers, he thought about the high likelihood that he would be killing civilians. He wondered if the killing had bothered his father. Maribelle had told John a story about squishing a bug while she and William sat on a park bench when he was in pilot training. “Why did you do that?” he asked. “You shouldn’t do that, killing things.”

Hesley had mostly bombed factories that produced war materials and the railways that moved soldiers and supplies. But by the winter of 1945, the Americans had broadened their target lists to include cities. On February 3, Hesley’s crew joined a 1,000-bomber armada from England that pummeled Berlin, an occasion when American bombers directly targeted civilians. How had his father felt about dropping bombs on people in Berlin, John wondered, like so many helpless little bugs down below?

John changed his mind and enrolled in a Presbyterian seminary, where his conscience was stirred by the civil rights and antiwar movements. As he rallied fellow Presbyterians to oppose the war, he thought about his father, who had volunteered for such dangerous duty, and worried what his mother would think of her son choosing the opposite course.

“If your father were alive, he would agree with you,” his mother told him. “This is not a good war.”

John served as a minister for several years, then trained as a clinical psychologist. Over the years he worked with several veterans, helping them process what they had seen and done in war. One man was haunted by the killing he’d done in Vietnam and felt he’d lost his humanity. A sailor, swallowed up by depression, wanted to go back to war, where he felt useful. A woman struggled with survivor’s guilt after watching her best friend die in an explosion.

All the while, as he helped ease their burdens, he kept his own grief and loss tucked away.

* * *

The Allied warning broadcast on the BBC was unusual for its time. The Hague convention of 1907 had stated, “After due notice has been given, the bombardment of undefended ports, towns, villages, dwellings or buildings may be commenced.” During World War II, few targets were considered “undefended,” since each side had radars and war planes at the ready. In 1945, Americans did drop leaflets into Japanese cities, urging civilians to end the war or face “the most destructive explosive ever devised by men.” But the leaflets didn’t specify that the attacks would be on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Skoda Works was different. The target was not on enemy soil but on land occupied by the enemy. The Allies issued a specific warning, even though it would give the Germans time to bring in reinforcements to the antiaircraft guns arrayed near Pilsen. With the formation stretched out for miles, the German gunners had a nonstop stream of targets.

In another squadron farther back from Hesley in the formation, several planes found a break in the clouds and had been able to drop their bombs on the first pass, but the commander’s plane hadn’t dropped its bombs, and he ordered his squadron over the radio to make another pass with him to maintain the integrity of the formation.

“If you are going back over again,” a pilot told him, “you are going alone.”

“Be quiet,” the commander said. “We are going around again. I don’t want to discuss it. It’s an order.”

“I’m married and have a little boy,” the tail gunner in another plane told his pilot. “I’m not going through that again. If you go around, I’m bailing out.”

The pilot wanted nothing to do with another run. He broke from the formation and started back for England with several other planes.

But most hadn’t been so lucky. They still had bombs to drop, so they looped around and lined up for another run through the field of flak.

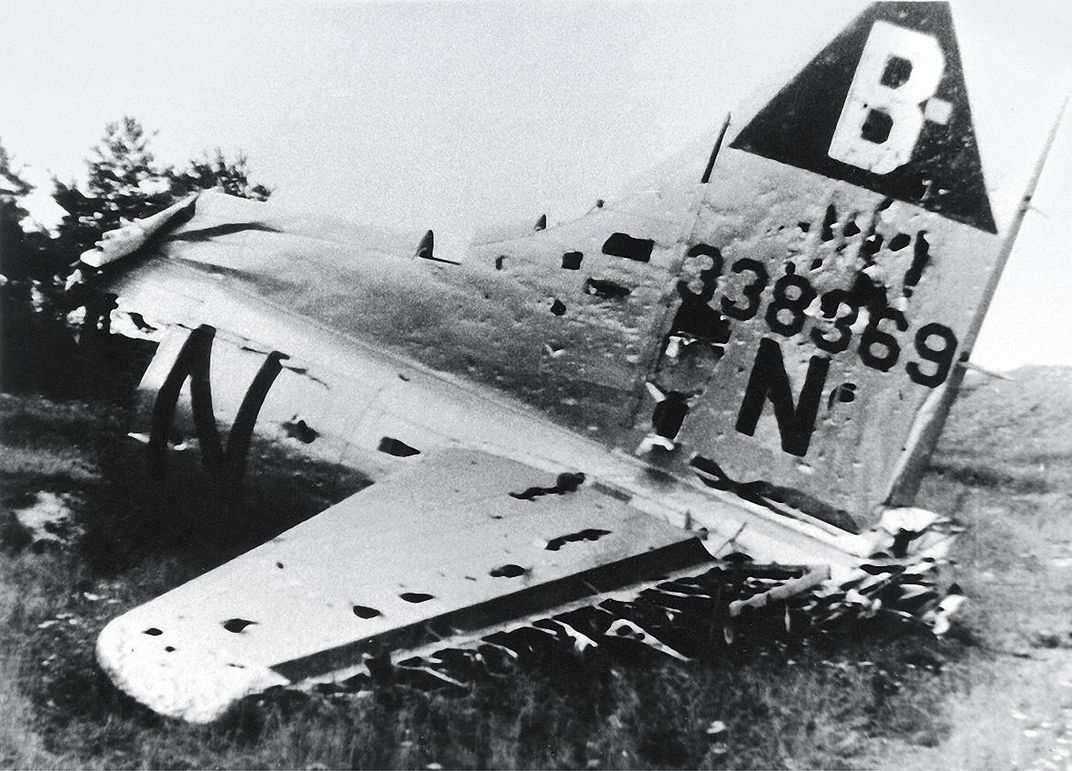

Checkerboard Fort, with Hesley huddled at his navigator’s desk, didn’t fare any better on the second pass. Clouds still covered the target. The bomb bay doors closed and the pilot, Lt. Fisher, banked the plane for an almost unheard of third pass. Fifteen minutes later, at around 10:30 a.m., they were lined up for another run. Fisher opened the cockpit door and called back to the radioman. “Hey, Jerry,” he said, “take a look at what we’ve got to fly through.”

From his little radio room behind the bomb bay, Jerome “Jerry” Wiznerowicz peered through the cockpit window at a sky blackened by explosions. In all his missions, he’d never seen it so bad. “Holy Christ almighty,” he said. “We’re not going to make it.”

On this third run, the clouds had parted over the Skoda Works complex. Neal Modert flipped the toggle switch and bombs poured from the belly of Checkerboard Fort.

Many of the crews hit the mark. Six people were killed on the factory grounds, and errant bombs killed 67 civilians in the city. But the bombers annihilated the Skoda Works, destroying or heavily damaging 70 percent of the buildings. Despite the chaos in the skies, the mission was turning out to be a great success.

Fisher banked the plane and they headed for home.

A moment later, an 88-millimeter shell tore through the two engines on the left side. The bomber tipped into a dive and Fisher rang the bell for everyone to bail out.

Crews in other planes saw Checkerboard Fort spin off to the left of the formation. A few P-51 escorts followed it down, looking for parachutes, until it disappeared into the clouds at 15,000 feet.

Just as Wiznerowicz fastened his parachute the plane exploded and broke in half. He fell out and tumbled through the sky.

The blast blew Modert through the plane’s plexiglass nose. Though injured by flak in the shoulder, he was able to pull his chute. Hesley and everyone else were trapped inside as the two burning halves of Checkerboard Fort pinwheeled through the clouds.

* * *

Last September John finally opened the box.

Preparing for his home office to be recarpeted, he emptied the closet where he’d stored it after his mother’s death 20 years earlier. He had seen many of the items before, like the two letters his father and mother had written to him, and the photo of the family walking down a street in Texas, Maribelle in a plaid dress, William in his uniform, with his son in his arms.

But he hadn’t before been ready to consider them in totality, and the story they told about his father, and himself.

John unrolled a three-foot-wide panoramic photo showing his father with his class of more than 200 men as they started navigator training in Southern California on April 25, 1944—his second wedding anniversary and a year to the day before his last mission.

He sifted through pictures his dad had with him in England, which were sent home after he died. John, a few weeks old, held aloft in his father’s hands. As a toddler, with an officer’s cap covering his head. More of him, playing and smiling, and photos of B-17s in flight, surrounded by flak explosions, stacks of bombs pouring from their bellies.

Maribelle had clipped a dozen newspaper articles about air raids, no doubt wondering if her husband had taken part in the attacks, if he was safe, or among the crews lost: “1,200 Heavies Hit Reich”; “1,300 8th Heavies Again Blast Reich as Nazis Hide”; “8th’s Blow Sets Berlin Ablaze.”

She had saved their marriage announcement from the local paper, and a final clipping:

“Death of W.F. Hesley Confirmed; Wife Notified Here Monday; Died Over Czechoslovakia”

John found the two Western Union telegrams reporting his father missing and then killed in action, and a half-dozen official letters of condolence. “Words can do little to ease your grief,” Gen. Hap Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, wrote, “but I hope you will be comforted by the thought that your husband faithfully fulfilled his duty to his Country.”

From the den of his home in Texas, Hesley searched the internet, reading histories of the bombing campaign in Europe, firsthand accounts from air crews, and stories about the last mission over Pilsen. For the first time he started to understand the horror of what his father had experienced. “I was overwhelmed by it for a while,” he says. “I would have nightmares, waking up in the middle of the night from dreaming about flying bomber missions.”

He reached out to military historians who scoured archives. They sent him lists of all the missions his father had flown, but he still didn’t know anything about his father’s last hours.

The Army had told Maribelle that he died instantly, but John always thought that was a kindness, saving family members from the bloody, awful details. He imagined his father burning to death, pinned inside the plummeting plane.

A niece of the Checkerboard Fort tail gunner, Staff Sgt. Chris Chrest, had searched through archives and found debriefings of the two survivors, Wiznerowicz, the radioman, and Modert, the bombardier. She sent them to John.

German patrols had captured them as soon as they landed in their parachutes, and held them as prisoners. Released at the war’s end two weeks later, they filled out reports about the Pilsen mission, which included questions about each crew member and when they were last seen.

For most of the crew, Wiznerowicz and Modert reported the same fate. Did he bail out? “No.” If not, why not? “Plane blew up. Pinned in and went down with the plane.”

But his father’s report was different. Did he bail out? “No.” If not, why not? “He was killed by flak.”

Relief washed over John. It was true. The blast that had taken out the two engines had killed his father.

His searching also put him in touch with historians in Pilsen. The city holds an annual festival that commemorates U.S. soldiers liberating the city from German forces on May 6, 1945. They invited John to attend the event as an honored guest, and to see the town the bomber crews had spared. They already knew about John’s dad. In Ceminy, the little town where the bomber crashed a few miles outside Pilsen, there’s a marble memorial etched with Hesley’s name, and the rest of the crew who died.

John had lived so long with murky memories and scraps of information that he hadn’t imagined this possibility: The story left forever unfinished when he was 2 years old might finally have an ending.

* * *

On an overcast afternoon in early May, John climbed into the front seat of a restored World War II-era U.S. Army jeep, driven by a Czech man dressed as an American soldier. A little convoy of old U.S. military vehicles loaded with local politicians and a dozen more re-enactors drove into the hills above Ceminy, a town of 250.

They stopped near a forest at the edge of rolling farm fields and gathered around a depression plowed out seven decades earlier when Checkerboard Fort slammed into the ground with William Hesley inside.

In the weeks leading up to their trip from Texas, John hoped that he and Jan might experience this moment alone, that he might grieve his father in private. But he understood the significance of his visit for a city still grateful for its liberation from the Germans and the lives saved by the BBC warning.

While the raid succeeded in destroying the factory and limiting civilian deaths, it didn’t have much lasting effect. The factory was rebuilt soon after the war and started producing heavy industrial machinery, locomotives and trucks that were shipped throughout the Eastern Bloc. Several Skoda companies, privatized after the fall of the Soviet Union, are still active today, building buses and railroad trains.

Even with the intensity of the flak that day, the Americans lost only six bombers, with 33 crewmen killed and ten captured. Eleven days later, on May 6, 1945, U.S. troops liberated Pilsen. At the Patton Memorial Museum in Pilsen John saw displays of weapons and uniforms, maps and patches, and mannequins dressed as victorious Americans, Czech civilians and surrendering Germans. His breath caught when he saw the ragged-edged piece of wing, about 4 feet wide and 9 feet long. He ran his hand along the metal that had carried his father here from England, the paint long faded, pockmarked with jagged holes where shrapnel punched through the skin.

“That was when it was real,” he says. “It moved it from being a story I had always heard about. Here was the evidence that it really happened.”

Out at the crash site the next day, where little pieces of wreckage still littered the ground, one of the re-enactors picked up a piece of metal that had been melted into a wad the size of a softball. He handed it to John. “It should stay here,” John said.

“No,” the man said. “You’re the person who should have this.”

John walked alone through the trees and looked out on the fields. He started to reconsider the narrative he’d told himself throughout his life. “I always believed that if he’d lived, my life would have been different and better,” he says. “After going over there and talking with the folks, it dawned on me, I don’t have any guarantee of that at all. If he’d lived, I don’t know who he would have been. I don’t know whether he would have come out damaged after getting into that B-17 every morning.”

Damaged like his stepfathers. And everyone else who came home from the Good War and suffered. And the widows. The man whose life his father had inadvertently saved by taking his place that day—did he struggle with guilt?

Compared with the tens of thousands of fatherless children, John knows he’s been lucky. Even without his father, his life turned out well, with a loving family, good friends and fulfilling work.

“There were all sorts of good people who just got ground up in the tragedy,” he says. “At some point you have to say ‘What happened happened.’ If he hadn’t gone, somebody would have gone. Why is his life more important than somebody else’s? That’s just how things went.”

His sense of loss has faded, replaced with an acceptance of the story told in the scorched piece of Checkerboard Fort that sits on his desk.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/16/cb164c14-5fdd-4759-a069-fa2c56ead414/b17-mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f7/88/f788cd52-c520-498b-b2de-f3d6f649afbb/b17s-longform-opener.jpg)