The Year of Jackie Robinson’s Mutual Love Affair With Montreal

Before he became a major leaguer, Robinson spent a formative year in the more hospitable environs of Canada

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/0b/690b21e7-cafa-42c0-9cd9-f41072d5710e/be065184.jpg)

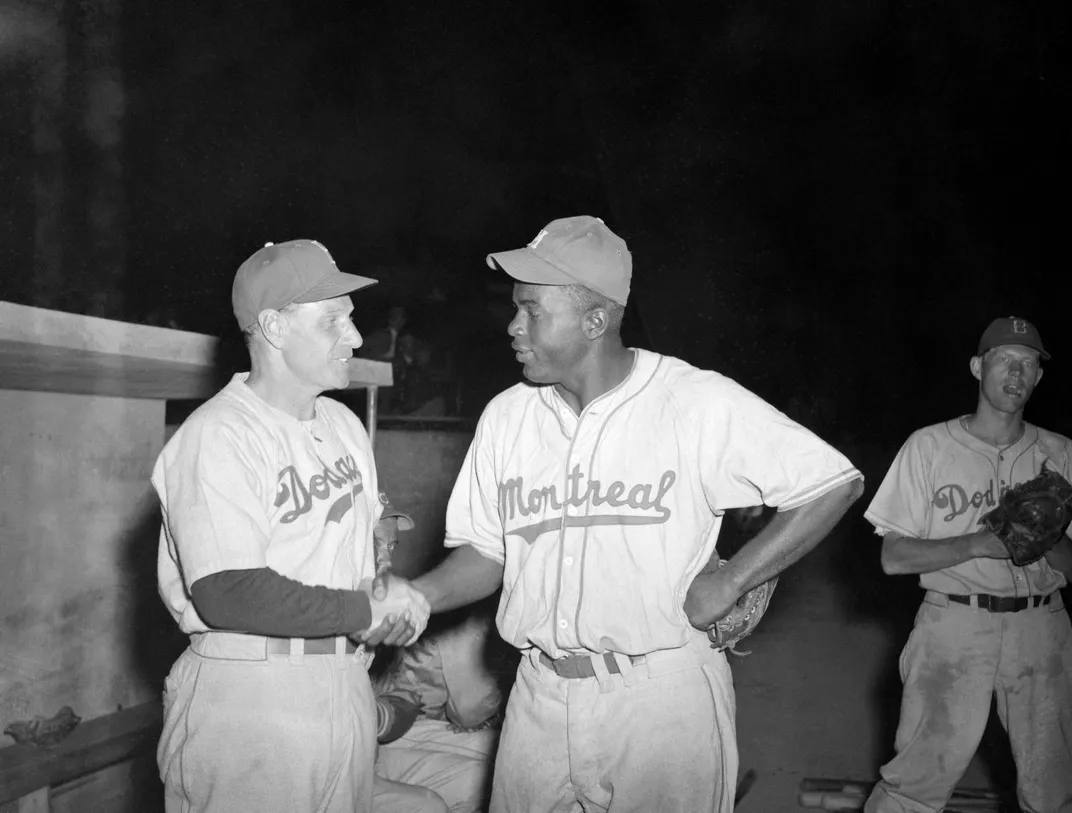

On April 18, 1946, Jackie Robinson, wearing a Montreal Royals jersey (#9) stepped to the plate in front of 52,000 raucous fans at the over-capacity Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City. As he settled in for his first official at-bat as a professional in an integrated baseball game, Rachel, his wife of just over two months, was pacing in the aisles, too nervous to sit. On a full count pitch, Robinson grounded out to the shortstop. It was the only out he’d make that day. His next plate appearance was a three-run homer; he was met with an outstretched hand by teammate George “Shotgun” Shuba, the first known photographed moment of black and white players saluting each other on a diamond. Robinson followed up the dinger with a bunt single, a steal of second, and ultimately a balk home after rattling the pitcher dancing down the third base line. Robinson’s final stat line was 4-5 with four RBIs in a 14-1 victory.

Plenty of opposing fans were belligerent, shouting out racial slurs, but many more in the crowd roared his every move. Robinson’s debut was indicative of the year he was about to have with the Royals, a season that is often overlooked in his storied legacy. It was pivotal, coming on the heels of a spring training experience in Florida that was also a harbinger of the bigotry and ugliness he would face throughout his professional career.

“Coming from California, Jack and I had never been to the Deep South and the treatment we received there was just horrendous,” says Rachel Robinson about her husband in an interview.

About eight months prior to that day in Jersey City, Jackie Robinson first met with Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey. In October, 1945, the team announced that Robinson had joined the organization for $600 a month with a $3,500 signing bonus, but Rickey had devised a plan to ease the future star and civil rights pioneer into the spotlight. Sending Robinson to play with the team’s triple-A minor league affiliate in Montreal was by design; Rickey felt it was the best place for Robinson to get acclimated to baseball in relative tranquility.

But first, the Robinsons had to endure a month of spring training in Florida. The Dodgers’ homebase of Daytona Beach, was relatively accepting for the time, but what they encountered in the Florida towns of Jacksonville, Sanford and Deland was hostility and bigotry.

Among the indignities the Robinsons suffered in spring training were getting bumped off of two flights with little or no official reason given (in both cases, their seats were given to whites), being shunted to the back of a bus on the way to Daytona by a driver who called him “boy,” not being able to dine with his teammates,, and being forced to live apart from the team in the home of Duff and Joe Harris, a local pharmacist and black leader. The Dodgers themselves weren’t immune from Jim Crow; they arrived in Jacksonville to find the stadium padlocked, and the game canceled because the lights weren’t working; it was an afternoon contest. For Robinson, racism even wore the same uniform. Years later, he would learn that early on, Rickey described a catch he made as a “superhuman play,” Montreal Royals manager Clay Hopper, a Mississippi native, responded, “Mr. Rickey do you really think a nigger’s a human being?”

In Montreal, the situation was the polar opposite. “We were still shaking from the experience we had before going to Canada,” says Rachel Robinson, who started the Jackie Robinson Foundation in 1973 to provide college scholarships to disadvantaged students of color and still serves on its board today.

“When we got to Montreal it was like coming out of a nightmare. The atmosphere in Montreal was so positive, we felt it was a good omen for Jack to play well,” says Robinson.

Jack Jedwab 56, a Montreal native and the executive vice-president of the Association for Canadian Studies, says that although it wasn’t utopia, in general, his home country was more idyllic. Canada doesn’t have the history and legally-enforced prejudice towards African-Americans found in the United States.

“The issue of race was not as fundamental a marker of identity in Canada as it was in the U.S.,” says Jedwab, author of Jackie Robinson’s Unforgettable Season of Baseball in Montreal. “It wasn’t an existential issue here, our conflicts centered around the ongoing conflicts between the French and English, Catholics and Protestants, they were more religiously based. Some experts argue there was slavery in parts of the British Empire in Canada, but it had nowhere the legacy of the American narrative.”

Peace of mind allowed Jackie to do what he did best, play ball. And what a season the Montreal Royals had, tearing up the Triple-A International League with a record of 100-54, ranked one of the top 100 minor league seasons ever according to MILB.com. The 27-year-old Robinson led the league in average (.349) and runs scored (113), while stealing 40 bases, driving in 66 runs and striking out just 27 times.

Robinson’s year in Montreal was an overwhelming success, but it didn’t entirely erase the memories from spring training, or the abuse he took during the season in towns like Syracuse, where players on the Chiefs taunted him and one threw a black cat on the field, yelling out that it was Jackie’s “cousin.” In mid-season, Robinson became convinced he was seriously ill. In his autobiography I Never Had it Made, Robinson admits that he wasn’t aware of the toll the abuse was taking and says he, was “overestimating my stamina and underestimating the beating I was taking.”

Rachel understood the true source of his tension, the Jim Crow south. “Jack was very angry in Florida, but he had to restrain himself,” says Rachel. “He also wasn’t eating or sleeping well, so we took time off. After he rested and reclaimed his faculties, he was fine for the rest of the season.”

Robinson’s brief bout of mental and physical exhaustion was no match for the young couple’s other amazing development in Montreal. Rachel was pregnant with their first child, Jackie Jr. (who was later killed in an automobile accident at age 24.) Once Rachel began showing, the eight French-speaking children who lived above the Robinsons always carried her groceries. “The neighbors were all friendly and protective,” she says. “The women came over and helped sew my maternity gowns and brought me rationing tickets because they said I needed to eat more meat.”

Whatever Jackie was eating, it worked. The Royals barnstormed their way to the “Little World Series” against the Louisville Colonels, one of only two teams below the Mason-Dixon line in the rival American Association. The series was set to open in Kentucky, but Robinson wasn’t allowed to stay in the team hotel. It was a big question of whether the Royals were even going to show up. Robinson found lodging, but the discrimination didn’t end there as the Louisville owners put a quota on the number of black fans that could attend the games. Robinson went into an ill-timed slump, going 0-5 in Game 1--the only time that happened all season--and 1-10 in the first three games, His spirits, and his bat, picked up when he returned home to a hero’s welcome. Royals fans were livid at the treatment he’d received and they packed Delormier Downs with full-throated force. Down 2-1, the Royals won the next three games with Robinson driving in the game-winner in the 10th inning of Game 4.

After the 2-0 series Game 6 clincher, and knowing Jackie was headed to greener diamonds, the fans mobbed him after a final curtain call. They hugged and kissed him, tore at his clothes, and Robinson’s sportswriter friend Sam Maltin of the Pittsburgh Courier wrote that there were tears in Robinson’s eyes when the masses lifted him onto their shoulders. Maltin famously described the scene as, “probably the only day in history that a black man ran from a white mob with love instead of lynching on its mind.”

After Robinson’s season, even Clay Hopper shook his hand and sang his praises, saying he’s “a player who must go to the majors. He’s a big-league ballplayer, a good team hustler, and a real gentleman.”

Royals fans certainly embraced Robinson, but surprisingly, his year in Montreal didn’t have staying power in the annals of Canadian sports lore. In part because baseball isn’t hockey, but also because, as Jedwab notes in Canada, it’s a sports story not a civil rights one.

Grantland contributor Jonah Keri, a Montreal native who wrote Up, Up & Away, the definitive history of the Expos, says growing up, the Robinson story wasn’t as ingrained with Canadian kids as it is in America. “My maternal grandfather, who lived in Montreal when Jackie was around, talked about the Expos rather than the old Royals,” says Keri. “That said, city councilman Gerry Snyder's quest to bring professional baseball back to Montreal in the late 1960s definitely had its roots in his affinity -- and Montreal's affinity -- for the glory days of the Royals. To this day, the only statue outside the Expos' old home park Olympic Stadium -- where Hall of Famers Gary Carter and Andre Dawson, and many other greats played -- is of Jackie Robinson.”

The statue was erected in 1987, and in 2011, the former de Gaspes Avenue home of Jackie, Rachel, and their future son was commemorated with a plaque and dedicated as a heritage site, preserved in baseball immortality. On April 15 of this season, the Los Angeles Dodgers will host the Seattle Mariners in major league baseball’s Civil Rights Game, the culmination of its annual Jackie Robinson Day where players throughout baseball don his retired jersey #42.

Breaking major league baseball’s color line will always be the centerpiece of Jackie Robinson’s legacy, but there’s one fan who will never forget his 1946 season with the Montreal Royals.

“In Jack’s book he said he owes more to Canadians than they’ll ever know. We were passionately in love and brimming with the anticipation of starting a family. I will always feel a deep sense of gratitude and appreciation for the attitudes of the people in Montreal,” says Rachel. “It had a lot to do with our future success.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_2851_thumbnail_copy.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/IMG_2851_thumbnail_copy.png)