This $34 Smartphone-Assisted Device Could Revolutionize Disease Testing

A new low-cost device that plugs into a smartphone could cut down on expensive lab tests

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/b6/73b69cfa-2ca9-43c3-8e31-8bc18de173ec/smartphone_testing_device.jpg)

In the near future, getting a blood test could be as simple as plugging an accessory into your smartphone and watching half an episode of your favorite sitcom while you wait for the results.

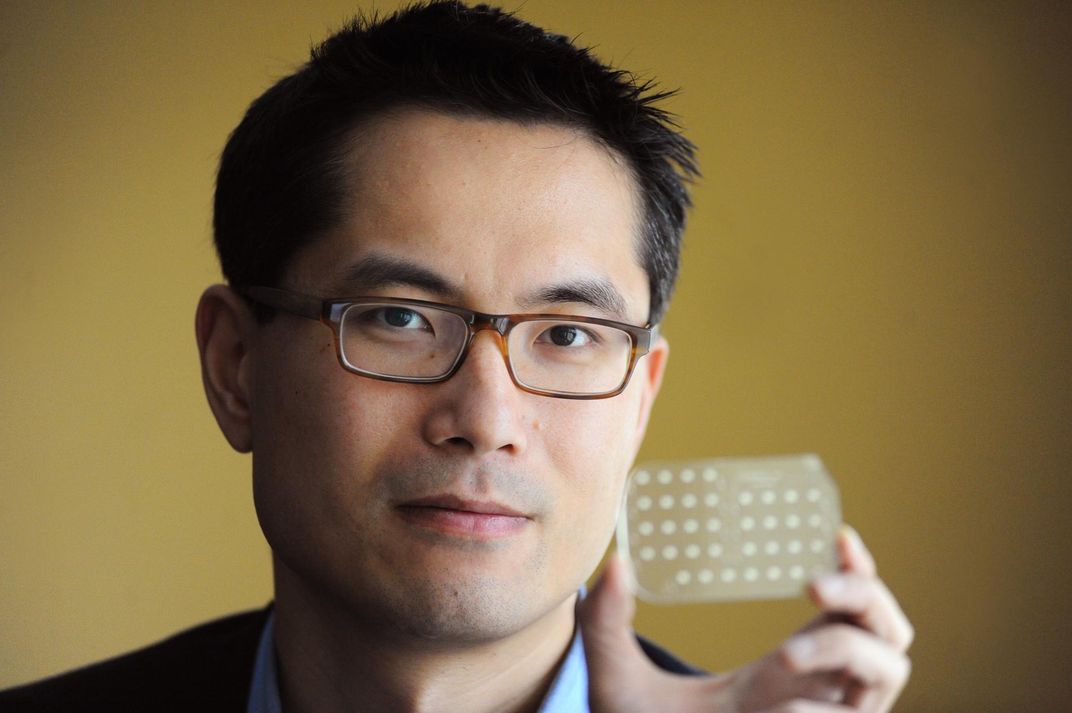

Researchers led by Samuel K. Sia, associate professor of biomedical engineering at Columbia University, have developed a tiny lab on a chip that, when fed a drop of blood from your finger and plugged into a smartphone, can test for HIV and syphilis in just 15 minutes. In contrast to the expensive, lab equipment that’s typically used for blood tests, the team says their device should cost just $34 to manufacture and is small enough to hold in the palm of your hand.

The test kit also gets all the power it needs through the smartphone’s headphone jack, which is also used to transfer data to the app to display and record results. This means the device can also be used with any type of smartphone, and could potentially be powered by less-expensive devices, like iPods and lower-end phones as well. One of the key goals was to keep power consumption as low as possible so the tool could be used in areas where power isn’t always available or reliable.

A user collects a drop of blood from a pricked finger into a small plastic cartridge with several tiny maze-like channels. Once the cartridge is inserted into the smartphone-attached device, pressing a large black button sucks the blood down different channels into a number of detection zones. Each of these zones searches for antibodies or antigens within the blood that indicate the presence of a particular disease.

Sia says that he and fellow researchers started working on the project a decade ago, before smartphones, focusing on miniaturizing the aspects of testing that actually deal with blood and fluids. The goal was to bring diagnostic tests to remote locations that don’t have the money or infrastructure to support large, expensive lab equipment.

“When the smartphone started being used by a lot of people we adapted our design,” says Sia. “There’s good reasons for doing that, because we can now put the functions of the lab-based test into our smartphone accessory, and all the other functions, like user interface, communication, and any sort of processing that you have to do with the information, we can directly leverage off the smartphone.”

The device’s abilities were put to the test recently in a pilot program in Rwanda, where it was used by health care workers to quickly screen 96 patients at three clinics for HIV and both active and latent syphilis. According to the published results, the device missed just one case of latent syphilis, making it 96 percent as accurate as standard lab tests.

There was also a 14 percent false positive rate when using the device. But because the test is inexpensive and fast, administering a second test to confirm in some cases wouldn’t be a major problem, particularly in remote locations with limited infrastructure. For these kinds of tests, traditional equipment costs close to $20,000 and requires a skilled operator and a lab.

While the device was used to test for HIV and syphilis in the recent field study, it isn’t limited to just testing for STDs—or even diseases in general.

“We do a kind of test called ELISA,” says Sia. “It covers certain infectious disease markers, HIV and syphilis and other infectious diseases, and chronic disease markers, such as some cancer markers, diabetic markers and cardiovascular. And it covers markers that have nothing to do with disease, actually, that are more health and wellness, so vitamin levels and hormones, that just tell you what’s going on in your body.”

The device can’t test for all these conditions at once, but would require different plastic cassettes (and a separate blood drop) to test for different markers or conditions. That means a broader lab-based test would still be better in some cases. Lab machines also process several blood samples at once, while Sia’s device is aimed at individuals.

“I don’t think [our device] is going to make lab tests obsolete,” says Sia. “But I think it’s going to start moving a lot of those tests away from a lab-type of facility, so that people have more options, so people can test at pharmacies, at homes, they don’t have to be in a hospital or go to a lab.”

Sia also says that, because the device is so inexpensive, people could opt to pay out of pocket if insurance doesn’t approve a particular test. But the team’s immediate goal is nobler and more urgent than making first-world blood tests a little more convenient. The group would like to complete a larger trial in the developing world, then bring it to market there first, so it can be used to diagnose pregnant women and help keep them from passing HIV and syphilis on to their children.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)