Can This Berry Solve Both Obesity and World Hunger?

At a playful café in Chicago, chef Homaro Cantu is experimenting with miracle fruit, a West African berry that makes everything a little sweeter

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/83/1d/831db13e-2262-467d-bc78-7be5a2bc506c/miracle_fruit.jpg)

The Chicago-based chef Homaro Cantu plans to open a new café with Wonka-esque ambitions. He will offer guests a “miracle berry”-laced appetizer that subsequently makes his lite jelly donut—baked without sugar—taste rich, gooey and calorific.

The concept of his Berrista Coffee, set to open next week on Chicago’s north side, rests on miracle fruit—berries native to West Africa that contain a glycoprotein called miraculin that binds to the tongue and, when triggered by acids in foods, cause a sweet sensation. Once diners down the berry, which will be delivered at Berrista in the form of a small madeleine cake, everything subsequently sipped, slurped and swallowed is altered, for somewhere between 30 and 45 minutes. In that time, mascarpone cheese will taste like whipped cream, low-fat yogurt will pass as decadent cheesecake, sparkling water with lemon will sub for Sprite, and cheap merlot will feign a rich port.

Miracle fruit doesn’t just amplify sweetness, it boosts flavor. “If you had a strawberry, it’s not just the sweet that goes up, but there’s a dramatic intense strawberry flavor,” says Linda Bartushuk, director of human research at the Center for Smell and Taste at the University of Florida, who has studied the effects of miracle fruit since the 1970s. “That’s why people get such a kick out of it. The flavor increase is impressive.”

European explorers of West Africa first discovered local tribes eating the fruit before insipid meals, such as oatmeal gruel, in the 18th century. Researchers in the United States have been studying its effects as a sweetener since the 1960s. The berries are considered safe to ingest, according to Bartushuk, but because they are exotic and still little known to the general public, they have yet to become part of our mainstream diet.

Guiding me on a pre-opening tour of his 1,400-square-foot shop, featuring an indoor vegetable garden at the front counter, the ebullient Cantu declares, “Let’s unjunk the junk food!” The Berrista menu will offer sugar-free pastries and dishes like chicken and waffle sandwiches that allow you to, in his words, “enjoy your vices,” without sacrificing your health.

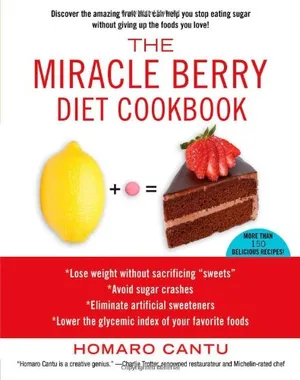

Cantu is a restless tinkerer who holds dozens of patents in food technology, including an edible paper made of soy. He once worked with NASA on creating a “food replicator” in space, much like the 3D printer in Star Trek. Cantu has been experimenting with miracle berries since 2005, when a friend complained her sense of taste had gone metallic as a side effect of chemotherapy. Last year, he published The Miracle Berry Diet Cookbook, giving dieters, diabetics and chemo patients recipes for whoopie pies, cakes and cookies as well as savory dishes, such as Korean beef with kimchi and spicy apricot chicken wings. Now, he hopes to introduce such berry-boosted dishes to mainstream commuters in the working-class Old Irving Park neighborhood, just two blocks from the I-94 expressway.

Miracle fruit, or Synsepalum dulcificum, grows on bushy trees, generally to about five feet. As part of Berrista’s indoor farm, Cantu plans to add a grove of 82 miracle berry plants in the basement by next spring, eventually shipping the harvest to the Arizona-based mberry that processes the fruit into tablets and powder, more potent concentrations than the berry itself, used by the restaurant.

As Cantu sees it, the berry and the indoor farm are solutions to health and hunger issues, as well as to environmental sustainability.

“Refined sugar is a dense energy storage product,” he explains, while offering me a sample of Berrista’s chicken and waffle sandwich, a leaner-than-normal version that, after I down a purple, aspirin-sized miracle berry pill, tastes just like the sweet-savory, maple-syrup-drenched dish. “Throughout history your body got used to consuming raw vegetables and meat, then cooked meat. Sugar is a relatively new invention, maybe in the last 300 years. Now your body, which has taken so long to evolve, has so much thrown at it, it breaks down.”

The menu, still in development, includes plenty of indulgences, such as donuts and paninis. Eliminating sugar doesn't make them calorie-free, but they are better-for-you options, the chef argues. He plans to price his menu items to compete with fast food rivals, making his version of health food economically accessible.

"I don’t necessarily think it’s going to be the next magic pill or silver bullet for our obesity epidemic," said Louisa Chu, Chicago-based food journalist and co-host of the public radio podcast “Chewing the Fat.” "But it gets us thinking and it may wean us from the sugar we take for granted and the hidden sugar in foods we don’t know about."

If the berries can alter flavor perceptions of treats like sugar-free donuts, Cantu reasons they can also feed the developing world on bland or bitter foods that are digestible, but considered inedible. To prove it, he once spent a summer eating his own lawn alongside miracle berries. “Kentucky bluegrass tastes like tarragon,” he reports.

His plans to scale-up the campaign are vague, but hunger is something Cantu knew intimately as a child in Portland, Oregon. “I grew up floating from homeless shelter to homeless shelter with my mom and sister,” he says. “A character building childhood, we’ll call it.”

By age 12, he began working in restaurants, spending his free time taking apart engines to see how they work. “I actually still do that,” he laughs. He earned his practical education in haute cuisine over four years at Charlie Trotter’s, the famed, now-shuttered, high-end restaurant in Chicago. Just before opening his first restaurant, Moto, in 2004, the 38-year-old took a brief hiatus to create edible paper for menus and other food-related innovations, including utensils with spiral handles that chefs can stuff with aromatic herbs and a hand-held polymer oven than can withstand temperatures up to 400 degrees Fahrenheit and still feel cool to the touch, both of which he uses at Moto. “Over the years, I started realizing in food there’s a need for invention, a need for practical applications, because there are so many challenges,” he says.

One of those challenges, as he sees it, is eliminating food miles—the distance a food must be shipped, which dulls the flavor of food over time and wastes considerable fossil fuels in transit. The Natural Resources Defense Council says the average American meal includes ingredients from five countries outside of the United States. After nearly four years and $200,000 spent perfecting his indoor farm growing herbs and vegetables at Moto in Chicago’s West Loop, he says he finally has the right combination of lighting, seeds and a syphoning water system that irrigates without using an electrical pump to make it productive, energy-saving and therefore financially viable.

If visionary Chicago city planner Daniel Burnham, who famously said, “Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood,” had a food counterpart, it would be Cantu, who envisions his indoor farms proliferating and disrupting today’s food system.

“Imagine if this whole neighborhood had access to zero-food-mile products and you were able to buy produce cheaper than at the grocery store up the block? This will happen,” he says with certainty, surveying the busy road on which Berrista resides, a block away from a Dunkin’ Donuts. “Now this is an opportunity for grocery stores to start doing this. This addresses so many problems, the California drought, plastics. We need to decentralize food production.”

One step at a time is not this chef’s multi-tasking, magic-stirring MO.