Childhood Leukemia Was Practically Untreatable Until Dr. Don Pinkel and St. Jude Hospital Found a Cure

A half century ago, a young doctor took on a deadly form of cancer—and the scientific establishment

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8a/28/8a288459-7db7-4298-b903-cd59c12ec5a0/julaug2016_a04_drpinkel.jpg)

It began in the summer of 1968, the summer after her kindergarten year. Barbara Bowles was a 5-year-old girl growing up in the drowsy river town of Natchez, Mississippi. Happy and seemingly healthy, a fetching gap between her two front teeth, she was an introvert with brown hair, the youngest of three. She took piano lessons and, with few neighborhood girls her age, became a tomboy by default. But that summer, coming in from her romps, she began to collapse in exhaustion. Her dad, Robert Bowles, then a technician for International Paper, noticed it first: How tired she was, the lost weight, the peculiar pallor that washed over her face. She complained that her joints ached and seemed to be having a lot of nosebleeds.

Robert took Barbara to the family pediatrician in Natchez, who examined her, ran some tests, drew some blood. And then, just like that, came the verdict: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL).

Under a microscope, the culprit was plainly visible in the blood smear. Deep in the marrow of Barbara’s bones, white blood cells were proliferating out of control. They weren’t normal white cells—they were immature structures called lymphoblasts, primitive-looking globules that seemed to have no purpose other than to crowd out her healthy blood cells. Coursing through her body, these cancerous blobs began to accumulate and take over, literally causing her blood to grow pale. (The word “leukemia” is derived from the Greek for “white blood.”)

Leukemia. The mere sound of it plunged Robert and his wife, Eva, into despair. Acute childhood leukemia was considered a nearly 100 percent fatal malady. Being a blood disease, it did not offer the solace of locality. There was no one place where it resided; it was everywhere, and always on the move. “A death sentence,” Robert said. “It left us in dread.”

ALL was the most common form of childhood cancer. The Bowles’ doctor referred to it as “the Wasting Disease.” He told the couple that nothing could be done for their daughter in Natchez—that, really, nothing could be done for her anywhere. He knew of a few children’s hospitals around the country that could likely prolong her life by a year or so. But after a brief remission, the lymphoblasts would surely return and continue multiplying inside her. She would become dangerously anemic. Infections would begin to attack her. She would suffer from internal bleeding. Eventually the disease would kill Barbara, just as it had in nearly every case of ALL the world had seen since 1827, when the French surgeon and anatomist Alfred Velpeau first described leukemia.

But the Bowles’ family doctor had heard of one place that was experimenting with new drugs for ALL. St. Jude, it was called, named after St. Jude Thaddeus, the patron saint of hopeless causes. Decidedly outside the academic mainstream, this newfangled treatment center—St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital—founded by the comic entertainer Danny Thomas on the largesse of America’s Lebanese-Syrian Christian community, was located in Memphis, 300 miles upriver from Natchez. When it had opened in 1962, St. Jude had turned heads by announcing that its doctors hoped to “cure” childhood leukemia. Most experts scoffed then—and were still scoffing.

But understandably, Eva and Robert were desperate enough to try anything. And so one hot, anxious day in the midsummer of 1968, with Barbara wan and spent on the back seat, they drove through cotton and soybean fields up the Mississippi Delta toward Memphis.

**********

I was born in Memphis the same year that St. Jude hospital opened its doors. As I grew up, I wondered about the improbable rise of this extraordinary institution that so quickly came to occupy a central place in the lore of my hometown. There was something mysterious about St. Jude; it seemed a semi-secret enterprise, bathed in a halo-glow. St. Jude has always appeared to be firmly in control of its publicity and zealously protective of its image. In back of those tug-at-your-heartstrings television ads and celebrity testimonials, significant pioneering triumphs had indeed taken place there. But how those successes had come about was not generally known and seldom talked about—even within the Memphis medical community.

Then, a few years ago, I was in Memphis visiting a friend whose son was being treated at St. Jude for an extremely rare and pernicious form of leukemia. Brennan Simkins, only 8 years old at the time, had undergone four bone marrow transplants. He would later enjoy complete remission with high prospects for a permanent cure (a success story chronicled in his father’s recent book, Possibilities). But when I visited Brennan in his hospital room that afternoon, he wasn’t out of the woods. With his resolute face, his thin smile, and his heartsick family gathered around, he looked much as Barbara must have on the day her parents had first brought her here.

In one of the brightly painted hallways, I met Bill Evans, who was then St. Jude’s CEO and director. Evans gave me a brief tour of the billion-dollar campus, with its state-of-the-art labs, cheerful wards and vast research wings, where armies of be-smocked scientists—and at least one Nobel laureate—plumb the mysteries behind all manner of catastrophic childhood diseases. Nowadays, the hospital treats more than 6,000 patients a year.

I asked Evans: How did this all...happen? Long before it became a fundraising juggernaut and one of the world’s most ubiquitous charities, St. Jude must have gone through a time of trial and worry and doubt, when its success was not inevitable. Who, or what, was responsible for turning the corner?

Evans didn’t miss a beat. “The moment of breakthrough was 1968,” he said, “and a clinical trial called the Total Therapy V Study.” Then a note of awe crept into his voice. “It all came about because of one man: Don Pinkel.”

This was news to me. In Memphis, everyone’s heard of Danny Thomas—and deservedly so. He’s buried in a mausoleum on the hospital grounds, with an important boulevard named after him that cuts through downtown.

But Don Pinkel? The Total Therapy V Study of 1968?

I heard the same reverential tone a few months later, when I spoke with Joseph Simone, a prizewinning oncologist in Atlanta who worked closely with Pinkel. “It wouldn’t have happened without Don,” Simone said. “He had the courage and the charisma and the idealism, and he provided the intellectual infrastructure to make St. Jude work.” Pinkel recruited the staff. He devised the protocols. He forged the relationships. He coaxed the drugs from the pharmaceutical companies. He wheedled the grant monies from the federal agencies. In its first years, he kept St. Jude afloat, though it had few success stories and sometimes could barely make payroll. “Don had a clear and noble vision,” said Simone, “and he created a culture of daring.”

Perhaps most important, it was Pinkel who decided, from the outset, to put the conquest of ALL at the heart of the enterprise. Said Simone, “Don’s the one who realized: It doesn’t do any good to extend the lives of those kids by a few months. You have to go for broke. You have to go for the total cure.”

And he did. In 1970, just eight years into his tenure at St. Jude, Pinkel was able to make an extraordinary pronouncement: Childhood leukemia, he said, “can no longer be considered an incurable disease.” The hospital was seeing a 50 percent cure rate—and had the literature to prove it. Today, building on protocols he and his staff established at St. Jude, the survival rate for most forms of childhood ALL hovers around 85 percent.

Donald Pinkel, it seemed to me, was one of America’s great medical pioneers. He had won some of medicine’s highest accolades, including the Kettering Prize, the Lasker Award for Clinical Medical Research and the American Cancer Society’s Award for Clinical Research. But outside of pediatric oncology and hematology, his accomplishments at St. Jude remained largely unknown—and unsung. So when I found out that he was alive and well and living in California, I had to meet the man.

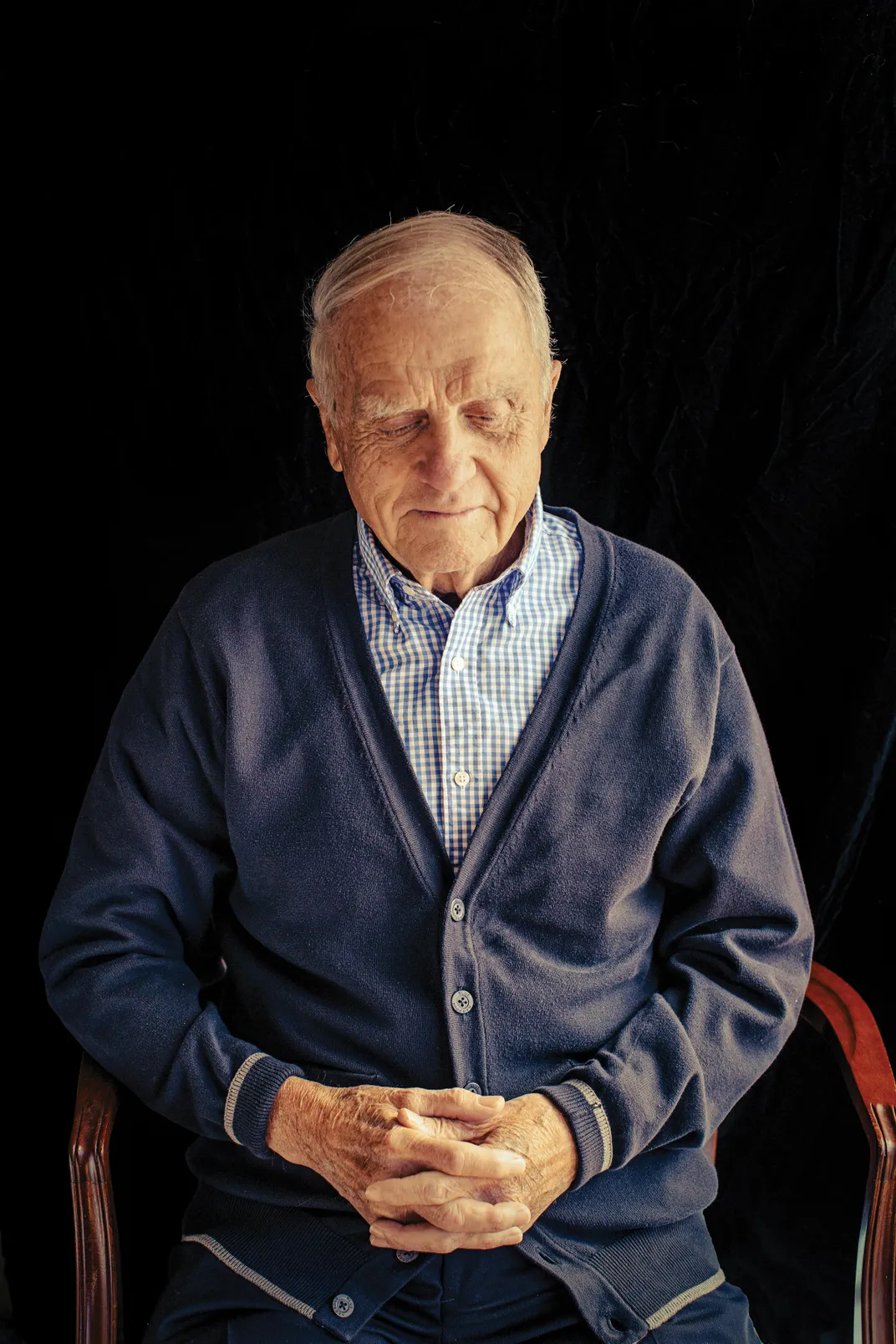

Pinkel lives with his wife, Cathryn Howarth, a British-born pediatric hematologist, in a book-lined ranch-style house in San Luis Obispo, a college town surrounded by patchworks of orchards and vineyards. Now 89 years old and retired, Pinkel is an avuncular man with a gentle voice, kind eyes and silver-gray hair.

I could see in Pinkel the quality Simone was talking about: A clear and noble vision. Whatever it was, the magic was still there. Jesuit-educated, he still has a rigorous mind, a fierce work ethic and a zest for attacking problems. “I’m a very stubborn person,” he says. “A coach once told me, ‘Never run from a fight—the farther you run, the harder it is to fight back.’”

Yet at St. Jude, during those early years, hope went only so far. “There were times,” he says, “when I would go into real despair.” When a child died, the parents would often come to him and unload their anger and grief. Pinkel would listen for hours and try to put up a strong front, assuring them this was not a punishment from God. “Then, after they left,” he says, “I would fasten the door and cry my eyes out.”

**********

When Barbara Bowles arrived at St. Jude, they put her in a room with another girl about her age. Then they took her down the hall to draw her blood and aspirate her marrow—inserting a thin, hollow needle deep into her hip to draw a sample.

Her parents didn’t tell her what she had. “I knew it was serious,” Barbara said. “But that’s all I knew.”

Barbara remembers the medicine room, where they dispensed the drugs by IV. One of them made her feel flushed, as though some hot electric barb were snagging through her. Another left such an acrid taste on her tongue that the nurses gave her candy to suck on. The drugs were potent. She couldn’t keep her food down. She was fuzzy and forgetful and irritable. She developed sores on her thumbs. Her muscles ached. She was so, so tired.

“Leukemia completely tears you apart—not just the child but the whole family,” said Barbara’s dad, Robert Bowles, who passed away not long after this interview, at age 87, earlier this year. “It preoccupies you. It takes over everything. You start to have a fatalistic attitude. But the doctors and nurses were so compassionate. They gave you hope.”

Barbara continued sharing a room with another girl. One day, though, the girl wasn’t there anymore.

**********

An irony: Donald Pinkel spent most of his career trying to vanquish one devastating children’s disease, but as a young man he was nearly killed by another. In 1954, then a 28-year-old pediatrician serving in the Army Medical Corps in Massachusetts, Pinkel contracted polio. One night, as the virus ravaged through him, he nearly stopped breathing. Through his fever haze, he thought to himself, “This is it. I’m not going to wake up.” For months, he was paralyzed. Having to rely on others to feed and care for him, he had good reason to believe his medical career was over. The Army retired him because he was unfit for duty and he spent the better part of a year in rehabilitation, learning how to walk again. Slowly, steadily, he graduated from a wheelchair to braces to crutches.

Even while he was recovering, Jonas Salk and Albert Sabin were becoming household names around the world for their historic efforts to produce a safe polio vaccine. It was a heady time for an ambitious young doctor like Pinkel, a time when the public was pinning ever greater hopes on miracles of medical science to eradicate the world’s most terrible maladies. As he continued to improve, Pinkel took a position with Sidney Farber, a legendary pediatric pathologist in Boston, who then was experimenting with a promising new drug called aminopterin, which, he found, could induce temporary remissions in some children with leukemia. Though Farber was far from finding a cure, his groundbreaking work planted a seed in Pinkel and set him on his life’s course.

In 1956, Pinkel accepted a job as the first chief of pediatrics at Roswell Park Cancer Institute, a prestigious research hospital in Buffalo, Pinkel’s native city. He loved his work there but found that Buffalo’s damp and freezing winter weather played havoc on his polio-compromised lungs, and he repeatedly contracted pneumonia. He knew he had to move to a milder climate; he didn’t think he could survive another Buffalo winter.

And so, in 1961, when he met Danny Thomas and heard about the new hospital the entertainer was building down South, the young doctor was intrigued. Pinkel had doubts about Memphis, however. At that time, it was a mid-sized provincial city surrounded by cotton fields—a fertile ground for musical invention, perhaps, but decidedly not on the map for cutting-edge medical research. “People thought I’d be crazy to go down there,” Pinkel says. “It was a very chancy situation, led by this Hollywood character. One colleague told me I would be throwing away my career.”

The state of race relations in Memphis also concerned Pinkel. “At first, I said I’d never move to the Deep South, because there was so much virulent prejudice down there.” But when he met with some of the hospital board members, they agreed with his insistence that St. Jude would treat all comers, including African-American children, and that the hospital would be integrated top to bottom—doctors, nurses and staff. As if to underscore the point, Danny Thomas hired Paul Williams, a prominent black architect from Los Angeles, to design St. Jude. In addition, the hospital’s board planned to devote significant resources to treating and researching sickle cell anemia—long a scourge in the African-American community.

Pinkel also expressed his concern that St. Jude should treat patients without regard to their family’s ability to pay. “I was sometimes called a communist,” Pinkel says, “because I didn’t think children should be charged for anything. Money should not be involved at all. As a society, we should make sure they get first-class health care. This, in fact, is the philosophy of most pediatricians.” A need-blind policy was Danny Thomas’ notion as well—and the hospital’s stated goal.

So Pinkel signed on: He would be St. Jude’s first medical director. He was hired on a handshake at the callow age of 34, with an annual salary (paltry, even then) set at $25,000. He drove his Volkswagen bug down to Memphis and arrived in the summer of 1961 to a curious, star-shaped edifice that was still under construction. Pinkel collaborated with the architects in revising the building’s interior spaces to create a workplace conducive to interdisciplinary exchange—one in which doctors and nurses would daily mingle with pathologists and researchers. Pinkel wanted everyone eating together in a central cafeteria, sharing findings, infusing each other’s work with a sense of urgency. He wanted a building that broke down boundaries between practice and theory, between the clinic and the lab. “The idea was to mishmash everyone up,” Pinkel says. “It was actually nothing new. This is what people like Louis Pasteur and Paul Ehrlich did. The idea is to get everyone thinking together, debating—concentrating on the problem at hand.”

“Pinkel wanted to create an environment of solidarity where everyone worked in the trenches together,” says Joseph Simone. “He wanted people to take risks and move ahead rapidly with bold new ideas. And he wanted to keep things small. Pinkel would be leading a few platoons, not an army.”

St. Jude opened in February of 1962 and the work began in earnest. The hours were brutal—“ten days a week,” says Pinkel—but he was enthralled by the challenge of creating something entirely new.

What Barbara Bowles remembers most vividly is the spinal taps, how much it hurt when they inserted the needle that dripped the chemicals directly into the base of her spine. “You got the sense the doctors were experimenting,” said her father, Robert. “They were very unsure about some of the side effects. They would change up the cocktail, trying to find something that would suppress the disease.”

After her therapy sessions, Barbara would return to her room and open her coloring book, but often found that she was too exhausted to work the crayons. “The routine just wore her out,” said Robert.

All the same, Barbara remembers St. Jude as a cheerful place. Toys. Puppet shows. Television. Ice cream. Parents stayed for less than $10 a night at the nearby Claridge Hotel. The kids were from all over the South, all over the country. Her parents reassured her that she was in the best possible place for treatment.

Still, Barbara did notice something odd: Her hair was falling out.

**********

St. Jude didn’t focus on just leukemia, of course. From the start, the hospital trained its resources on an array of devastating diseases—including cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, sickle cell anemia and brain tumors. But it was Pinkel’s ambition to “cure” ALL that caused consternation among his medical colleagues back East. Some thought it was irresponsible, the kind of quest that would give parents false hope. “At that time, with ALL, the idea was to try to prolong life in comfort—that was it,” Pinkel says. “We called it ‘palliation.’ No one thought you were going to ‘cure’ anybody. That was almost a forbidden word.”

Still, there had been tantalizing developments. By the early 1960s, a number of agents had been found that could temporarily induce remission in ALL patients. They were highly toxic substances with draconian tongue-twister names like mercaptopurine, methotrexate, vincristine and cyclophosphamide. Up to that point, doctors tended to give these chemotherapeutic drugs to their patients serially—that is, one at a time, a regimen known as “monotherapy.” Each medication might work for a while, but invariably the doses proved insufficient and the patient would relapse. Within months or even weeks, the cancer would return. Doctors might move on to the next drug, achieving the same short-lived remission. But soon enough, another relapse would occur. The disease was so furtive, resilient and adept at hiding in the body (especially the meninges—the membranes enveloping the brain and spinal cord) that no single drug could knock it out.

Pinkel’s idea—drawing on pioneering work then underway at the National Cancer Institute—was to use what he called the “full armamentarium.” That is, combine all the drugs known to induce remission and administer them to the patient more or less concurrently, at maximum tolerable dosages, over a sustained period. In addition, he would employ radiation of the cranium and the spine to reach the disease’s final redoubts. Finally, he would continue to administer multi-drug chemotherapy for three years to “eradicate residual systemic leukemia.” It would be a regimen so relentless, multifarious and prolonged that the disease would be permanently destroyed. He called it “Total Therapy.”

“We said, ‘Let’s put it all together. Let’s attack the disease from different directions, all at once.’ My hypothesis was that there were some leukemia cells that were sensitive to one drug and other cells that were sensitive to another. But if we use all these drugs at once and hit them along different pathways, we would permanently inhibit the development of resistant cells.” This intensive approach of simultaneously using multiple agents had been tried, with hugely successful results, in the treatment of tuberculosis. Why not try it with leukemia?

Pinkel realized, of course, that the Total Therapy protocol carried large risks. Each of these drugs, used alone, could have dangerous, even fatal side effects. In combination, who knew what they would do? “I really worried that we were going to push these youngsters to the very brink,” he says. “On the other hand, you had to weigh the bitter fact that they were going to die anyway.” Through the early pilot studies, he and his staff would constantly refine the dosages, improve the methods of delivery. Pinkel’s staff would closely follow their patients, checking their blood weekly, and sometimes daily, to determine how they were tolerating this witch’s brew of medicines. Pinkel recognized that he was quite literally experimenting on children—and this troubled him. But he saw little alternative. Says Pinkel, “We were tired of being undertakers.”

For the first several years, with every new case admitted to the hospital, Pinkel sat down with the parents, explained to them his radical approach, and gave them a choice to participate. Not one parent declined. Many, in fact, looked at the situation altruistically. “They would tell me, ‘We know our child is not going to live. But if there’s something you can learn by treating our child that might one day lead to a cure of this terrible disease—please, please go ahead.’”

**********

By the end of the summer of 1968, Barbara’s leukemia had gone into remission. St. Jude released Barbara, and she went back home to Natchez just in time for first grade. “It raised our spirits,” said her dad. “But we were still so apprehensive.”

Barbara’s mom gave her a wig to wear, and a variety of caps, but Barbara found it all so awkward. She didn’t know what to tell her friends. By then she knew she had some form of cancer—but cancer was widely misunderstood then; many kids thought it was a contagious disease, that you could “catch” it on the playground.

Every Tuesday, Barbara would report to her pediatrician’s office in Natchez to continue with her intravenous chemo treatments as prescribed by St. Jude. And several times a week, she and her family would go to the Lovely Lane United Methodist Church. Congregants held regular prayer meetings there, and would single out Barbara for special attention.

In the fall, when she went back to St. Jude for a checkup, the news was promising: Her remission was holding.

By 1968, Pinkel and his staff had completed the first four studies of the Total Therapy protocol. These trials offered a glimmer of hope: Between 1962 and 1967, a total of seven patients had enjoyed long-term remissions and seemed well on their way to full recoveries. Seven was by no means a definitive number, Pinkel conceded. “But it said to me, it’s not necessarily so that they’re all going to die.” It also suggested that the underlying concept of Total Therapy was working; it just needed fine-tuning.

And so in early 1968, he and his staff started afresh with a new cohort of 35 patients—one of whom was Barbara Bowles. Who could have predicted that that year of national convulsions, the year when Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered on a motel balcony just a few miles from the hospital, would prove the watershed year in the history of this disease?

In the Total Therapy V Study, Pinkel placed greater emphasis on attacking the disease’s last holdouts, those drug-resistant leukemia cells that secreted themselves within the membranes of the central nervous system. His new protocol would retain certain elements from the first four studies, but he would carefully revise the dosages while adding a few entirely new elements, including the use of methotrexate injected “intrathecally”—that is, directly into the spinal canal—to head off meningeal relapse. Pinkel and his staff began to administer the new protocols and waited for the results—which, given the time-lagged nature of both the disease and its treatment stages, took many months to trickle in.

But when the data finally arrived—bingo. Something in this new iteration of therapies worked. Thirty-two of the 35 patients attained remission. After five months, not one had relapsed. And after three years, half the patients were still in remission. By 1970, they were considered long-term survivors, all but declared cured. Pinkel could scarcely believe his own numbers. A 50 percent cure rate? This was beyond astonishing; it was historic.

In this eureka moment, one can only imagine the euphoria that surged through the corridors of St. Jude. “We were all excited,” says Pinkel. “This was better than winning a football game, I’ll tell you.” He realized that the hospital was sitting on a giant secret that now needed to get out into the world; lives depended on it. “I sent my best people in different directions,” Pinkel recalls, “and we gave papers all over the place saying it was now possible to cure this disease.” They penned articles for the Journal of the American Medical Association, the New England Journal of Medicine and other important periodicals. Yet to Pinkel’s dismay, he was met with sharp skepticism. Many experts simply refused to accept St. Jude’s findings.

Some went further than that. Alvin Mauer, the highly reputed director of hematology/oncology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, all but called Pinkel a fraud. “He wrote me a letter saying I have no business telling people leukemia was curable, that I was foolhardy, and deceiving everyone. He really laid into me.” So Pinkel invited Mauer to come to St. Jude and see for himself. “I said to him, ‘You’re like Doubting Thomas, in the New Testament. Why don’t you come down here and feel the wounds?’” Mauer accepted. He met with the patients, examined the charts and histories, toured the wards and labs. And he was sold. “Mauer became one of our biggest advocates,” Pinkel recalls with a chuckle.

By 1973, the Total Therapy V results had generally become accepted. “It was pretty gutsy what Pinkel had done,” says Stephen Sallan, a leukemia expert at Boston’s Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and a Harvard pediatrics professor. “He had found a way to treat ALL in the central nervous system, and he was sitting in the catbird seat. We were all paying attention.” Suddenly, it seemed, everyone was knocking on the hospital’s door. Joseph Simone remembers “a tsunami of doctors” coming to St. Jude to learn the protocol. Soon other U.S. hospitals were using the Total V methodology—and achieving the same extraordinary results. Pinkel traveled internationally to spread the news; he even made a trip to the Soviet Union to share his findings with Russian doctors. “What bothered me more than anything,” says Pinkel, “was that Total Therapy required tremendous amounts of manpower and expensive technologies that weren’t available outside the United States. I thought children all over the world should have the same opportunities as American children.”

One of Pinkel’s other great regrets was that the Total V protocol exposed children to radiation and noxious chemicals that he feared could cause lifelong complications, growth problems, even other forms of cancer. In subsequent studies, Pinkel sought to dial down the most toxic dosages. Pediatric cancer researchers eventually dispensed with the use of radiation altogether, but there was no avoiding the fact that the zealous treatments pursued at St. Jude—like cancer treatments everywhere—carried real hazards.

It was Pinkel’s fervent hope that science would someday find a vaccine that would prevent ALL, so that none of the Total V treatments would even be necessary. For a time, he and his staff worked on a vaccine, to no avail. Pinkel has long had a hunch that ALL may be caused by a virus (as is true of some forms of leukemia found in cats and rodents). If science could isolate that virus, and develop a vaccine from it, then children could be immunized against ALL, just as they’re immunized against diphtheria, mumps, polio and measles. “That’s what I always hoped for,” Pinkel says. “Prevention is always the better way.”

So far, that dream is unrealized. But over the past half century, the 50 percent cure rate established by the Total Therapy Study has not only held—it’s steadily, emphatically improved. The key components of ALL treatment remain just as Pinkel designed them. To combat the disease, physicians use many of the same drugs—vincristine, methotrexate and mercaptopurine, agents that were approved by the FDA in the 1950s and 1960s, then combined into treatment protocols by Pinkel’s team. These subsequent leaps toward an overall cure rate approaching 90 percent were made possible, in part, by the development of better antibiotics and antifungals for fighting infections, by the advent of better diagnostic tests for detecting residual leukemia cells, and by the use of genomics to select the optimal drugs and doses for individual patients. Although these and other new techniques and medications have been added to the ALL arsenal, they have in no way replaced the basic protocol that Pinkel established all those years ago. Today, childhood ALL is frequently cited as one of the great triumphs in the war on cancer.

After publishing his findings and consolidating his breakthroughs at St. Jude, Pinkel soon considered a change. In 1974, he resigned as the hospital’s director and took a series of eminent hospital and faculty posts—in Milwaukee, Los Angeles, Houston, Corpus Christi. He was a builder, he realized, not a stayer. “I would set things up and get things rolling,” he says. “Then I would move on.”

While enjoying his retirement in San Luis Obispo, he has found that his polio symptoms have returned with a vengeance. He walks with a cane now, and often has to use braces. He stays busy swimming, reading medical journals and keeping track of his ten children and 16 grandchildren. From time to time he hears from his Total Therapy patients—they’re scattered around the world now, with their own families and careers, and grateful to be alive after all these years. He has reportedly been considered for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, and still occasionally lectures on medical subjects, at nearby California Polytechnic State University (Cal Poly). “Medicine isn’t a job,” he says. “It’s a life. You’re always on call.”

**********

For two years, then three, Barbara Bowles’ remission held. Although she continued her chemotherapy sessions in Natchez and did regular follow-ups at St. Jude, she remained in school without interruption. “My parents would drive me up there every year,” she says. “It was so scary—the whole time, I’d be saying to myself, ‘Are they going to find something?’”

When she was 12, her hair grew back in an entirely new color: A brilliant silver-gray.

In 1980, twelve years after her ordeal began, doctors at St. Jude brought her in for yet another checkup. Only this time, they said, “You’re cured. You don’t have to come back.”

Today she is Barbara Extine. She is a calm, stoic woman with rosy cheeks and a beautiful nimbus of silver-gray hair. She lives in Vicksburg, with her husband, Roy. She has a degree in geology, has finished her coursework for her master’s and has done contract work for years as an environmental scientist for the Army Corps of Engineers. She’s active in her church and is an avid gardener. Barbara hasn’t been able to have children, and has had health problems that are likely related to her leukemia treatments—including a malignant tumor that led to the removal of her bladder.

But she knows she’s one of the lucky ones. Lucky enough to be connected with a piece of history, one of the kids who just happened to show up in exactly the right place at exactly the right time, under the watch of a kindly doctor on the cusp of a breakthrough.

“I’m so happy to be here,” she says. “Cured. That was the word they used. You can’t imagine the relief. You just can’t imagine it.”

Related Reads

The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/hampton.png)