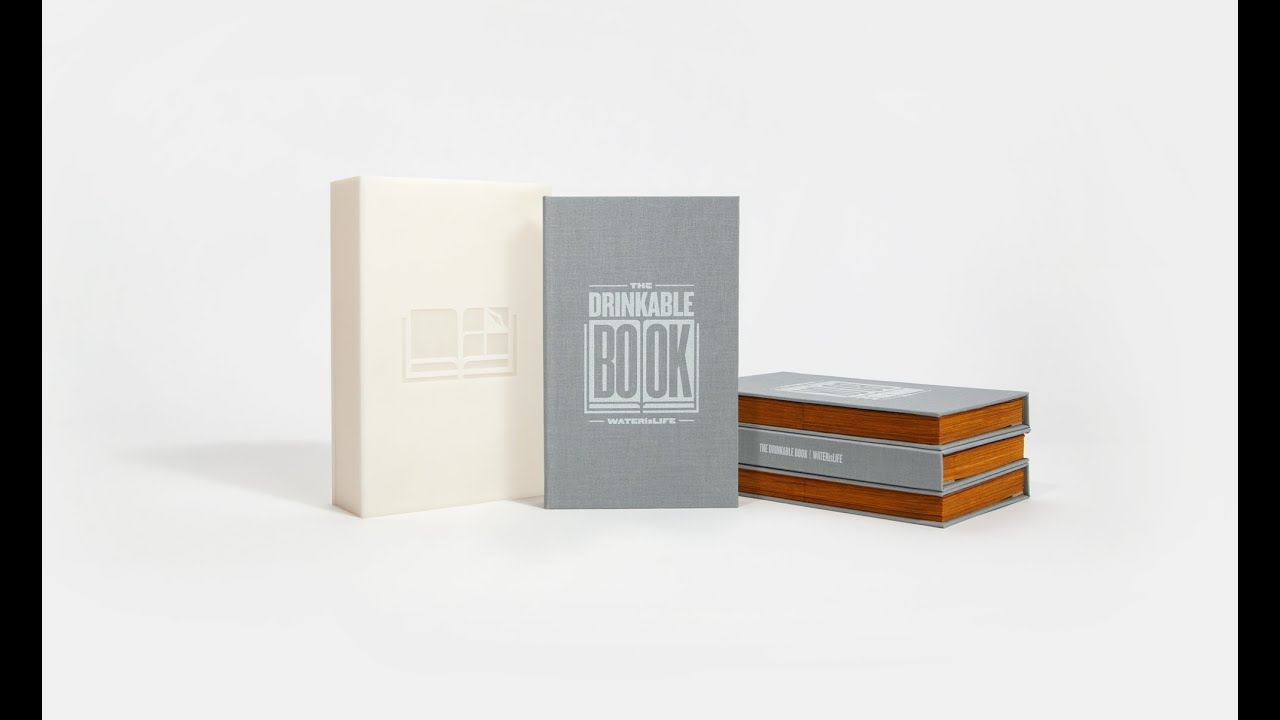

Could This ‘Drinkable Book’ Provide Clean Water to the Developing World?

Pour untreated water over a page from the book and silver nanoparticles embedded in it will kill nearly 100 percent of disease-causing bacteria

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/22/25/2225ee84-9258-47d8-b973-fe9ed936fa2e/1795341_10152439701367407_3664205042201614602_o.jpg)

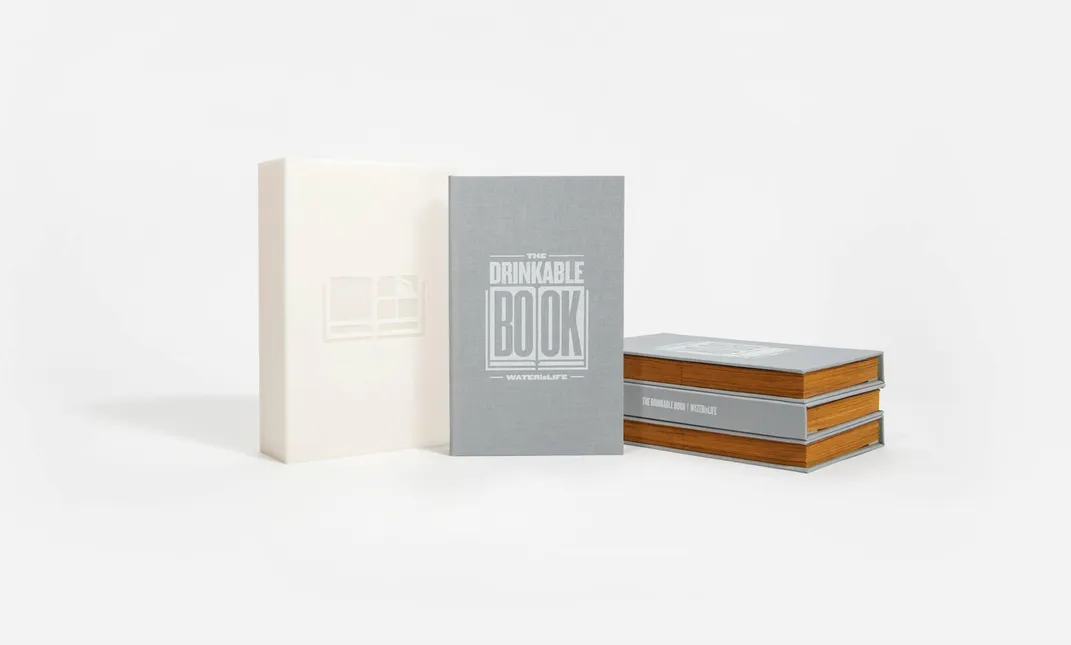

Perhaps we shouldn’t give up on paper books just yet. One in particular, called The Drinkable Book, might be a lifesaver. The hardcover with sturdy pages infused with bacteria-killing silver nanoparticles is a patent-pending water purification system.

Silver nanoparticles release silver ions, which render disease-causing microbes that get near them inactive, explains John Tobiason, professor of environmental engineering at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

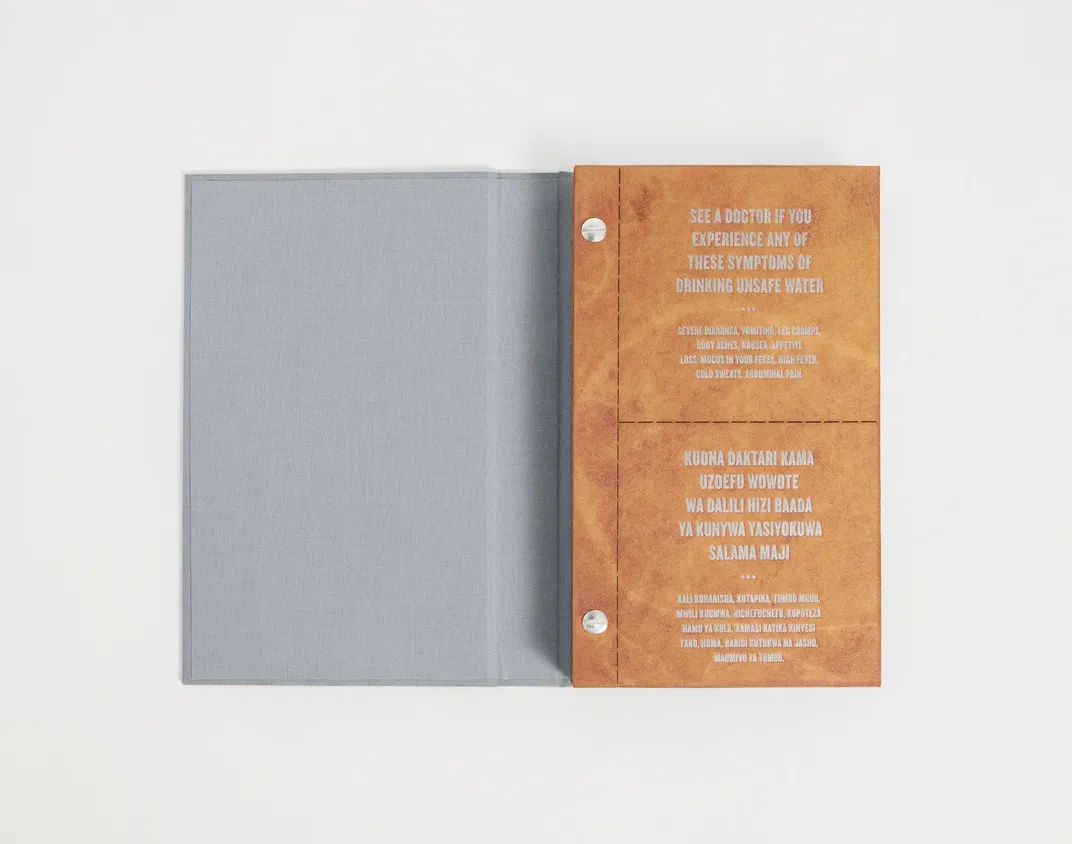

The pages of The Drinkable Book are embedded with these particles, which in field tests in five different countries eliminated nearly 100 percent of bacteria that causes waterborne diseases, such as typhoid, cholera, hepatitis and E. coli. But they are also stamped with brief messages about water safety.

“It’s both a guide of how and why you would need to clean your drinking water and also a means to do so,” says Theresa Dankovich, the creative mind behind the technology. She began researching antimicrobial paper as a PhD candidate in chemistry at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec.

To clean water, a user tears a page out of the book, slides it into the appropriate slot in the accompanying custom filter box and then pours water into the box, passing it through the purifying paper. The length of this process depends on the turbidity, or number of particles, in the water, but it is ready to drink as soon as it passes through the paper.

According to Dankovich, one of her filters can clean up to 26 gallons of water, and at that rate, the 25-page book could clean water for one person for about four years.

When she set out to create this purifying paper, Dankovich, now a researcher at Carnegie Mellon University, imagined inventing a product that could be used in emergency situations in North America. But once she learned more about the problems caused by drinking water all over the world, she realized her invention had the potential to be “really good for humankind,” she explains.

The filter is portable and easy to use, and unlike other water cleaning processes that use chemicals such as chlorine or iodine, there is no off-taste to the water cleaned by The Drinkable Book.

“The main thing is that it would fit in someone’s normal life without requiring massive changes to adopt such a technology,” says Dankovich.

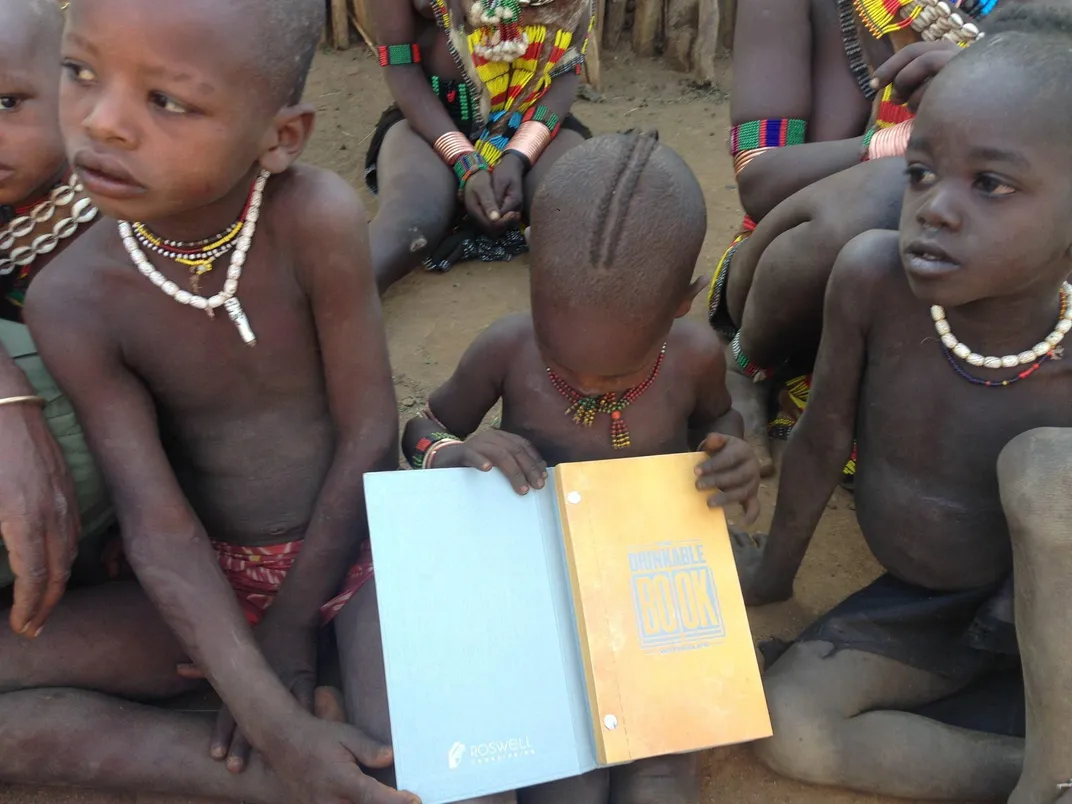

Dankovich began her field tests about two years ago in South Africa, when she was a post-doc researcher at the University of Virginia. She was testing the paper herself, not asking community members to test it. But she found that her paper filtered almost 100 percent of the bacteria. While she was there, designer Brian Gartside contacted her about collaborating with the non-government agency Water is Life, an organization that aims to improve drinking water in developing countries through community based action groups and the distribution of personal water filters, such as filter straws and, now, The Drinkable Book. It was Gartside’s idea to transform the paper into a guidebook that could be translated into local languages. The cost of the book is yet to be determined, but Water is Life is asking donors to give $50. The organization is raising funds to help produce the books, and Ken Surritte, the organization’s founder and CEO, hopes they will be ready for distribution in the field by the end of this year.

Earlier this summer, Dankovich teamed up with iDE Bangladesh, an NGO that designs programs to alleviate poverty, to conduct sociocultural research for the development of the book. Through focus groups and surveys, Dankovich and her team engaged over 500 people in southern Bangladesh. They found there are regional differences in water treatment resources. While a plastic bucket may be an appropriate water receptacle for communities in sub-Saharan Africa, a gourd-shaped aluminum container called a kolshi is much more familiar to Bangladeshis.

Though she designed her paper to kill numerous microbes, Dankovich learned that one of the biggest water problems in Bangladesh is algae, an organism she had not previously considered in her design. Algae is found in pond water, which the Bangladeshis prefer to cook with because it does not contain the rice-darkening properties found in tube well water. Although her book appeared to clean algae-contaminated water, she will have to complete further tests to determine the effectiveness of the filter paper on the algae.

These community specific challenges are examples of problems that she has to consider as she moves into larger scale product design and manufacturing. Up to this point, she has manufactured each page by hand with the help of students in her lab. For lab and field tests, and copies of the book, she has produced some 2,000 sheets of filter paper.

The effectiveness of water purifying devices depends on the initial quality of the water, the amount of water being purified and the commitment of the user, Tobiason notes. But he thinks that point-of-use products like this, which treat water where it will be used rather than where it is sourced, are a component of an overall solution to solving the water crisis in developing countries.

“The first step is sanitation,” Tobiason says. “And on the water side it’s to build up the capacity to support people at point-of-use and to support community water supplies.”

While The Drinkable Book is still in its early stages of development, Dankovich aims to move into larger scale production soon. She presented her findings today at the American Chemical Society’s 250th National Meeting & Exposition in Boston, Massachusetts.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_0154.JPG.jpeg)