Fast Forward: 3D Building Blocks Are the Secret Of This Old (Digital) House

Researchers have printed 3D houses before—but this attempt, using recycled material in a classic Amsterdam style, can be rearranged for different needs.

Four hundred years ago, when architects began to build tall, narrow houses along Amsterdam’s winding canals, they invented a style that would become popular around the world.

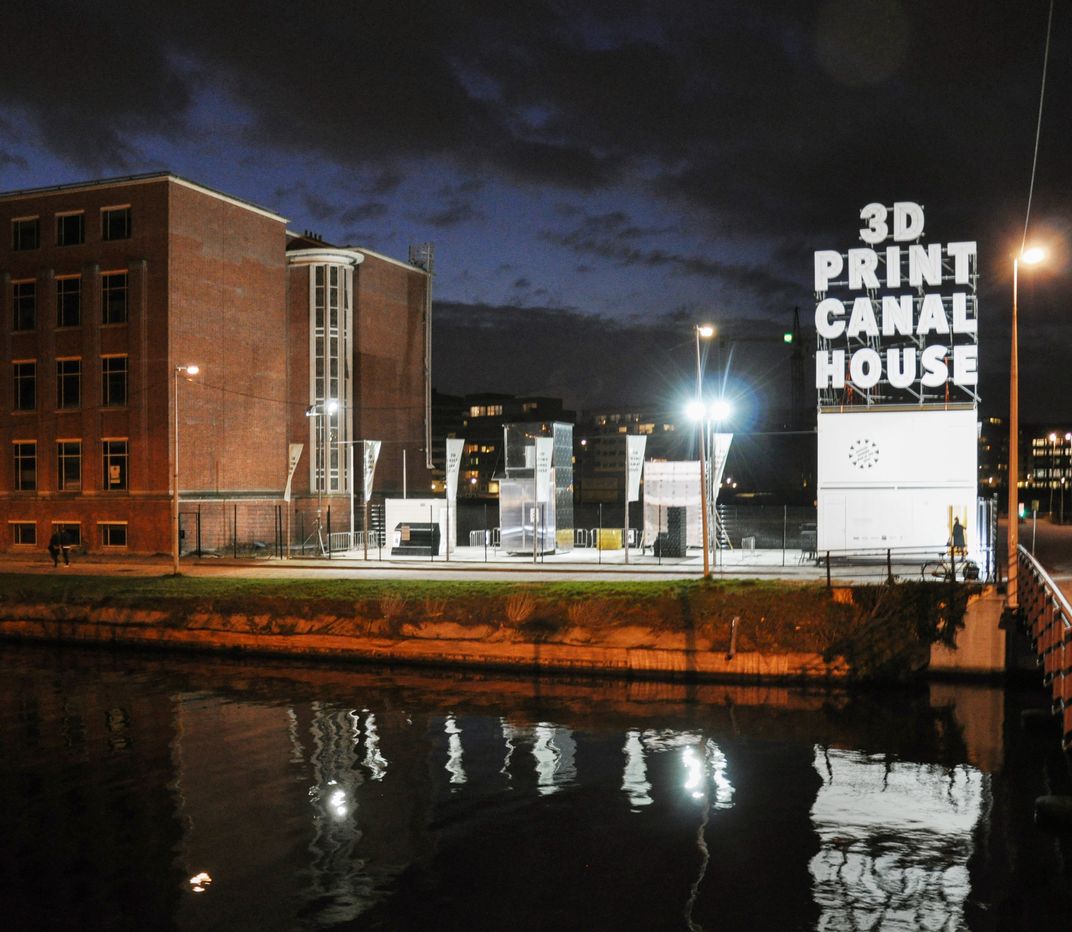

Now, designers from the Dutch firm DUS Architects are re-imagining the structures in a very modern way, breaking ground on what could become the world’s largest 3D-printed structure.

Dozens of industries, from athletic wear to health care, have chased after 3D printing in the past few years. Construction isn’t new to the game, but most efforts have focused around individual building parts—steel rods or concrete beams, for instance. Much of the race in housing has focused on speed: In China, one company recently built 10 houses measuring 2,100 square feet each in a day, and a professor from University of Southern California says he can build a 2,500 square foot house—including the plumbing and wiring—in about 20 hours.

DUS’ venture, though, has loftier aims—for large houses but also structures that could conceivably be used for shops or restaurants. It also relies mostly on recycled materials and claims to better handle more complicated design elements (which means, beyond disaster and poverty relief, 3D printed houses could also help repair or add to the veneer of historic neighborhoods without as much aesthetic disruption).

It also, unlike the other projects, is inviting the public into the process.

As in traditional construction, the process begins with blueprints. Digital design files are fed into a device called the KamerMaker (“room builder”), a 20-foot-tall printer that converts a digital design into code. The machine prints the interior and exterior of a room in a single round, squeezing recycled bioplastic layer by layer from floor to ceiling, leaving space for pipes and wiring.

Once completed, the individual rooms become three-dimensional building blocks. For the pilot project, blocks will be stacked to form a 13-room house overlooking one of the city’s central canals.

Though the first room in that project won’t be done until this summer, the venture—open to the public as an expo—could revolutionize modern architecture, designers say. The blocks can be rearranged to create different layouts depending on occupants’ needs. Since the house is printed and assembled on-site, says expo manager Tosja Backer, there is little waste and minimal transportation costs. And digital design files can be sent to sites around the world and then produced locally, says expo manager Tosja Backer, “to suit the location and context.” In areas struck by disaster, for instance, the KamerMaker could print with local waste materials.

Granted, it will be some time before we reach the age of print-it-yourself houses. It will take three years to complete the house, DUS says; along the way, designers are bound to hit roadblocks and challenges, some of which they may not be able to solve on their own. But in some ways, Backer says, that’s the point: Because the site is both an open workplace and exhibition, anyone, from engineers to visitors who pay the $3 entry fee, can help improve the technology.

“Sharing knowledge helps a project grow,” he says. “A building project is not just about the building: it’s about the context, the users, and the community. They are all part of the process.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/erica-hendry-240.jpg)