The Future of 3D-Printed Pills

Now that the FDA has approved Spritam, an anti-seizure drug and the first 3D-printed pill, what’s next?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/14/3e14b4d7-e913-4682-8dbd-bc98e3edaac9/istock_000049099534_large.jpg)

These days, 3D printing seems poised to take over the world. You can 3D print prosthetic limbs, guns, cars, even houses. This month, another 3D printed product has hit the market, this one with potentially much wider reach: 3D printed pills.

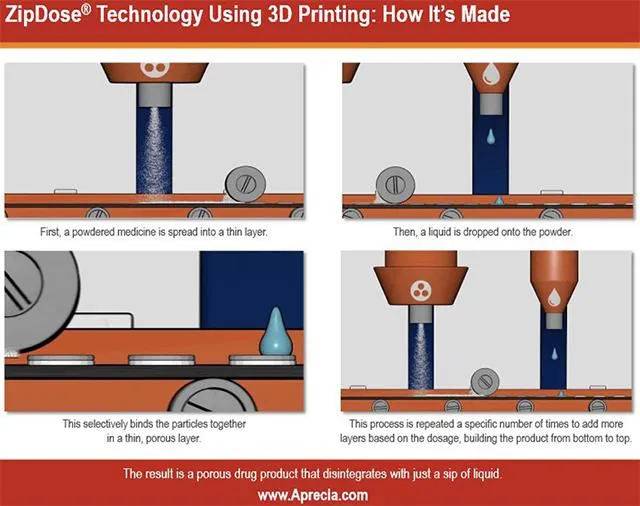

The first 3D printed pill, an anti-epilepsy drug called Spritam, was recently approved by the FDA. Created by Ohio-based Aprecia Pharmaceuticals, Spritam is made with Aprecia's proprietary 3D printing technology, ZipDose. ZipDose creates pills that instantly dissolve on the tongue with a sip of liquid, a potential boon to those who have trouble swallowing traditional medications.

“We intend to use this technology to change the way people are experiencing medicine,” says Don Wetherhold, the CEO of Aprecia.

The technology behind ZipDose was first developed at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where researchers began working on 3D printing in the late 1980s. They first printed pills in 1997. Though those pills were early and experimental, they set the stage for years of more research. Aprecia bought out the pill-printing technology in the early 2000s.

The ZipDose printer is about 6 feet by 12 feet. Using a small nozzle, it lays down a thin disc-shaped layer of powder. The printer then deposits tiny droplets of liquid on the powder, to bind it together at a microscopic level. These two steps are repeated until the pill reaches its proper height. The final product looks more or less like any regular pill, just slightly taller and with a rougher exterior. While most medications use inert filler material to create the body of the tablet, ZipDose technology allows the active ingredients to be squeezed into a smaller space. So one small pill can have a relatively high dose of medication, meaning patients have to take far fewer tablets.

Dissolving instantly is particularly important for a drug like Spritam, which curtails seizures. A patient in the throes of a seizure episode can’t sit down with a pill and a full glass of water. ZipDose-created pills could also be useful for children, who traditionally have difficulty swallowing tablets, as well as the elderly and those with neurological issues or dementia.

Aprecia plans to develop more 3D-printed medications—“an additional product per year, at least,” Wetherhold says. They may partner with other drug companies and manufacture those companies' drugs on the ZipDose platform. Aprecia will also be looking into using the technology for purposes other than prescription pharmaceuticals, Wetherhold says, such as over-the-counter medicines or nutritional supplements.

Medication-printing technologies could revolutionize the pharmaceuticals industry, making drug research, development and production considerably cheaper. This could make it more cost-effective for pharmaceutical companies to study drugs for rare diseases and ultimately make the product itself more affordable, though these savings are likely years away. No price has been set for Spritam yet, but officials at Aprecia say it will be in line with other anti-seizure meds on the market.

In the future, it may even be possible to print pills at home. For some, this idea is thrilling. AIDS patients in Sub-Saharan Africa could print their own antiretroviral drugs for low prices. People in the developing world could stop worrying about fake or low-quality drugs flooding the market. Getting here would, of course, take many steps and likely many years. A personal-sized printer would need to be invented and made affordable. Inventors would need to figure out how to supply the printers with their raw ingredients. Some researchers envision patients going to a doctor or pharmacist and being handed an algorithm rather than a prescription. They'd plug the algorithm into their printer and—boom—personalized medicine.

Lee Cronin, a Glasgow University chemist, has been an evangelist for the idea of democratizing medication with personal “chemputers” capable of producing any number of drugs.

"Imagine your printer like a refrigerator that is full of all the ingredients you might require to make any dish in Jamie Oliver's new book," Cronin told The Guardian in 2012. "If you apply that idea to making drugs, you have all your ingredients and you follow a recipe that a drug company gives you.”

Others wonder whether 3D printing technology will be a boon for drug dealers and drug addicts. If you can print a seizure drug, why not ecstasy or methamphetamines? This is all speculative at the moment, but it could easily become a reality once personal-sized printers hit the market.

But long before we see either home "chemputers" or 3D-printed illicit drugs, we’re likely to see a whole lot more lab-made, easy-to-swallow medicines.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)