How Are Universities Grooming the Next Great Innovators?

Design and entrepreneurship courses at Stanford and other institutions are fundamentally changing higher education

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/55/f1/55f1d58b-f083-4027-b5a6-40a1a95fba8f/100412-245.jpg)

Y Combinator is the Stanford of startup incubators. With an acceptance rate of less than 3 percent, it is known for launching superstars, such as Dropbox, AirBNB and Reddit. For a fledgling startup, getting into the exclusive program (which takes in two classes of about 85 companies each year) can feel like a “Hail Mary” opportunity for mentorship and investment. Perks of the three-month program include weekly dinners with tech and business luminaries, hands-on guidance with fundraising and product development, and the opportunity to pitch top investors at a Demo Day at the end.

Meanwhile, Stanford University accepted 5 percent of its applicants for this coming fall. The most selective in the country, the school is the alma mater of PayPal's Peter Thiel, Instagram cofounder Kevin Systrom and the team behind Snapchat. But, to continue to groom some of the country’s leading entrepreneurs and thinkers, it and other academic institutions are realizing that college, in some ways, needs to become a four-year incubator, approaching higher education in a fundamentally new way.

David Kelley, a mechanical engineering professor and founder of IDEO, along with a group of other faculty members including professor Bernie Roth, started Stanford’s d.school in 2004. The school, open to undergraduates and graduate students, emerged as a place to further promote the human-centered approach to learning, problem-solving and innovating already practiced in Stanford's design program, a fusion of engineering, art and technology coursework established in 1958. With the d. school, Kelley told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2010, "Stanford can be known as a place where students are trained to be creative."

Stanford is one of the earliest higher education institutions in the country to apply design thinking across fields, equipping students with the ability and mindset to tackle difficult global problems in industries from healthcare to energy. In d.school courses, students observe, brainstorm, synthesize, prototype and implement their product ideas. “Students start in the field, where they develop empathy for people they design for, uncovering real human needs they want to address,” notes the description on the d.school’s website.

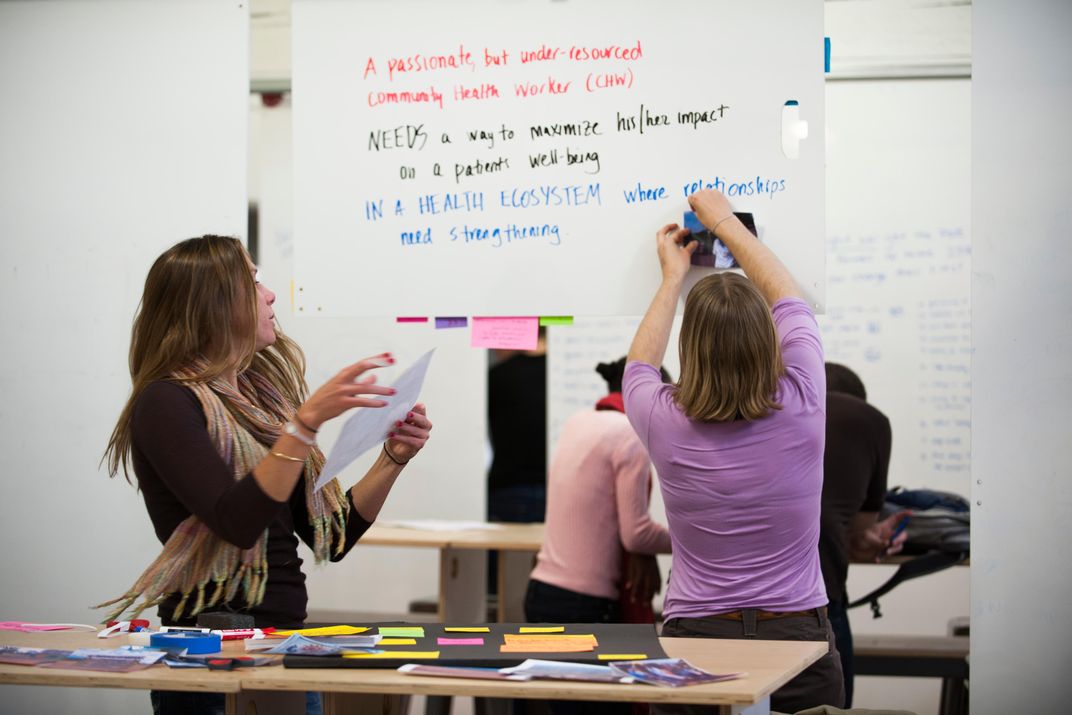

Once a very small room in a deserted building on the outskirts of campus, the popular d.school is now housed in a state-of-the-art, 30,000 square-foot building that was constructed in 2010, centrally located a stone’s throw away from the school’s signature Memorial Church. The industrial space is a brainstormer’s paradise, filled with whiteboards, flurries of colorful post-it notes, bright furniture, conference rooms and rows of collaborative workstations that expand and contract based on need. There are also physical and digital prototyping spaces with hand tools and software for creating products.

While the d.school does not offer its own degree, it has more than 30 classes and workshops taught by 70 instructors from various backgrounds, and more than 750 graduate and undergraduate students across disciplines enroll each year. The classes—some of the most popular on campus, with extensive waitlists—ask students from all backgrounds, not just business and engineering, to take a fresh look at the world around them and improve its existing inefficiencies.

In a course called “Design for Extreme Affordability,” students have helped address water scarcity, infant mortality, sanitation, malnutrition and care for burn victims in 21 countries in the past ten years. To research an issue, they collaborate with a partner organization and travel to the country where that organization is based to speak with residents of local communities about the major challenges they face.

“Designing Liberation Technology” is jointly taught by political science professor Joshua Cohen, system designer Sally Madsen of IDEO and computer science professor Terry Winograd and looks at the role that mobile technology can play in spreading democracy and development in Africa. “LaunchPad: Design and Launch Your Product or Service,” open to graduate students, is a rigorous, 10-week bootcamp on product development. “If you do not have a passionate and overwhelming urge to start a business or launch a product or service, this class will not be a fit,” its online description warns.

Since it launched, demand for d.school courses has more than quadrupled. And it’s growing popularity should come as no surprise—67 percent of Millennials in the United States aspire to start their own business or have already done so, according to a poll conducted by Bentley University in 2014. In a 2011 Stanford Alumni Innovation Survey, 61 percent of those the survey terms “quick founders,” individuals who received venture capital funding within three years of graduation, said they were exposed to courses in entrepreneurship during their time in college.

***

Alaa Taha took her first d.school course, ME101: Visual Thinking, in 2013, as a sophomore. The class taught her how to quickly visualize and prototype product ideas. “I loved the way I was challenged to create what I envisioned in my mind,” she says.

She went on to take six other courses at the d.school before graduating this June with a bachelor's degree in product design. She worked on projects for Caltrain, Target and the San Francisco Unified School District during her studies and designed and manufactured a robot that mimics the motion of ants, a drip coffee set-up made from steel tubing and her own interpretation of a traditional working lamp. Beyond the practical skills she gained, Taha learned to remove personal biases and create products tailored to the needs of the audience in question.

“Our context or environment gives us a certain lens,” she says. “A lot of classes have been about breaking down that lens and leaving my bias at the door.” To figure out how to improve the commuting experience for bikers using Caltrain, for example, she spent hours at different stations talking with riders of the rail, which connects San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara counties.

“It's a lot about doing," says Taha, "to prototype an initial concept, to have a user try it and see what works.”

***

Across the country, higher education institutions are establishing new degrees and courses, building innovation labs and maker spaces, and launching startup competitions and hackathons. In 2013, in collaboration with the National Advisory Council on Innovation and Entrepreneurship (NACIE), 142 research universities agreed to promote these particular lenses of study at their institutions. More than 500 colleges and universities have already established programs specifically focused on innovation and entrepreneurship. Schools are trying to keep up with the demands of students, wannabe Mark Zuckerbergs who have seen the meteoric rise of startups like Facebook.

Serial high-tech entrepreneur and professor Edward Roberts published a study, “Entrepreneurial Impact: The Role of MIT,” in 2009, which looked at the financial ripple effect of MIT alumni’s startups on the broader economy. According to the report, current companies founded by MIT graduates make hundreds of billions of dollars—enough that if the ventures combined to form their own country, that country would be the 17th-largest economy in the world, at the very least. And that’s not to mention the hundreds of thousands of jobs the companies create.

Under the leadership of MIT’s president L. Rafael Reif and his predecessor Susan Hockfield, the school’s commitment to innovation and entrepreneurship has gone from being a talking point to an institutional prerogative. The university created two new Associate Dean positions dedicated to these topics in 2013. At the same time, Reif spearheaded the launch of the MIT Innovation Initiative, which spans all five schools at the university and focuses on developing new programs to promote invention, creativity and entrepreneurship. One idea that’s emerged from recent efforts is the creation of an innovation and entrepreneurship minor at MIT.

Construction is also underway on a new facility called the Gateway Building. As its namesake implies, the building will function as a literal and figurative bridge between the academic haven of MIT and the companies adjacent to its grounds in Cambridge’s Kendall Square—one of the most esteemed biotech and IT hubs in the world.

While an emphasis on innovation has intensified, so too has the debate about whether a traditional and steeply priced four-year college education is necessary for budding entrepreneurs.

Zuckerberg famously dropped out of Harvard in 2004 after his sophomore year to work full-time on Facebook. (At a 2012 talk at Stanford, he encouraged young entrepreneurs to use college as a chance to "explore and develop new interests.") The brilliant, successful dropout has become a character ensconced in pop culture. In the Forbes 400 list of the richest people in America in 2014, the magazine notes that 63 out of the 400 individuals only have a high school degree. Students, poised to develop something new, seem to face a choice: stay in school and simultaneously pursue their idea or drop out and go full-time.

“To look at it from the student’s perspective, sometimes it makes sense to stay in school and sometimes it makes sense to drop out,” says Robert Sutton, professor of management science and engineering at Stanford. “Some of the best innovation classes we teach put them in a position to drop out.”

One of the most prominent advocates for an alternative route to traditional education is PayPal founder and serial entrepreneur Peter Thiel. He developed a two-year fellowship program in 2010 that individuals can join in lieu of attending an institution of higher education. As some have plainly put it, Thiel pays students to drop out of college; he grants each lucky fellow $100,000 to start a company. The website for the fellowship opens with a carefree-looking photo of its members on a beach and a Mark Twain quote: “I have never let schooling interfere with my education.”

Sean Parker, founder of Napster, has also questioned the value of a college education. In Michael Ellsberg’s 2011 book, The Education of Millionaires, Parker says, “When incredible tools of knowledge and learning are available to the whole world, formal education becomes less and less important. We should expect to see the emergence of a new kind of entrepreneur who has acquired most of their knowledge through self-exploration.”

***

In his 2014 book, Excellent Sheep, William Dersiewicz, a former English professor at Yale, lambasts the Ivy League system for imposing one-size-fits-all ambitions upon students who come in with varied interests and goals and, he argues, leave as carbon copies of one another.

“Our system of elite education manufactures young people who are smart and talented and driven, yes, but also anxious, timid, and lost, with little intellectual curiosity and a stunted sense of purpose: trapped in a bubble of privilege, heading meekly in the same direction, great at what they’re doing but with no idea why they’re doing it,” he wrote in an opinion piece for The New Republic.

Sutton, too, states that students can be constrained by the expectations that are currently imposed on them in a traditional system of higher education. “Whether you drop out or not, there’s this belief that there’s a pyramid and you are climbing your way from one level to the other, and if you take the wrong step, you’re going to get moved off the pyramid,” he says.

By offering courses on innovation, colleges aren’t just adding another subject matter—they are fundamentally shifting how they approach the path that students can take in school and the way they confront questions and problems after graduation.

“It’s getting away from this model of lockstep education,” says Patricia Greene, chair of entrepreneurial studies and former undergraduate dean at Babson University.

There is a growing consensus that higher education, moving forward, should be a flexible experience that can be customized in both subject matter and structure to fit individual interests and learning styles. There is no longer one template that can be interchangeably applied to every student’s path.

More than 900 colleges and universities now afford students the opportunity to create their own majors, tailoring a field of study to fit their specific interests. If you are interested in healthcare and engineering, why not major in health systems engineering? This way, you are equipped to actually prototype design ideas with practical applications.

In addition to vocational training, professors and students argue that college offers aspiring entrepreneurs unparalleled access to intelligent peers and mentors, and a risk-free testing ground for their ideas. The d.school welcomes a mix of professors and students with backgrounds in business, law, engineering and other disciplines to create a “nice tension,” says Sutton.

A key role of higher education is also broadening an individual’s worldview. “There is always a bias when you go at it alone,” says Dayna Baumeister, founder of the Biomimicry Center at Arizona State University, which focuses on building inventive ideas derived from behaviors in nature. “But, when you’re in a school environment, when you’re learning from your peers and your faculty, it removes some of that natural bias.”

Additionally, students and professors say that college can help provide a foundational compass for not only how to address challenges, but also how to choose which ones to tackle. Rajan Patel, a former student of Sutton’s at Stanford, cofounded Embrace, a social enterprise that provides low-cost infant warmers to vulnerable babies in developing countries. He highlights his experience at the d.school as vital for determining what areas he was interested in ultimately working in. “The techie stuff can be empowering and enable you to solve problems, but which problems will you choose to solve? What does it mean to be a good citizen, and how will you do that?” he says.

“We’ve innovated a lot and changed a lot, but if we project out 20 to 30 years, what kind of world do we want to live in?” asks David Edwards, an engineering professor at Harvard and the founder of the course "Engineering Sciences 20: How to Create Things and Have Them Matter." His class forces students to confront a key world challenge in the world and develop a product to address it within one semester. Edwards sees college as providing both a comprehensive understanding of different subjects and the tools needed for students to build inventions that will have a positive impact on society in the long-term. “There’s a real need to have a deep understanding of a complex world and to also think out of the box,” he says.

Currently, in many institutions, courses on innovation and entrepreneurship help lay the necessary groundwork for approaching a problem, inventing a product and starting a company. Professors often ask students to analyze cases of different businesses, glean from their success or demise and apply those lessons in launching their own product or experience. Students conduct extensive interviews and research on their products’ target audience, build prototypes and then test them.

“Think about what you want for yourself,” says Eric von Hippel, a professor of entrepreneurship at MIT. “Now, let's start to see how you can quickly and economically make that and try out to see if other people want it too.”

These courses essentially teach students what to do with an idea. They provide step-by-step guidance on taking an idea from concept to reality. “There’s a little bit of a perception that innovation is like the light bulb, about having the idea and voila,” Baumeister says. “But it’s actually hard work—you have to roll up your sleeves and be intentional about it. There’s an express intention in the classroom.”

The classroom is also a place for experiments to take place unfettered by financial recourse. While it may be a bubble, the college environment is safe, in that it provides the opportunity to take large risks and pursue ideas without significant repercussions. “The beauty of doing it in the classroom is that your job is not on the line,” says Baumeister.

Liz Gerber, a 2007 graduate from Stanford and d.school alumna, is now a design professor at Northwestern University, where she has helped establish a similar design thinking program.

Yuri Malina, one of Gerber’s students, started SwipeSense, a venture focused on promoting physicians’ hand hygiene, after graduating in 2011. His repeated practice of business development in class is what prepared him for the experience. “I had already been there six times before. If that was the first time I was doing it, I would probably have frozen up. I had been through the motions several times in this sheltered environment,” he says.

“Actually trying something is very different from learning about it in theory,” says Von Hippel. “I could explain kitesurfing until we're blue in the face, but you won’t be able to do it until you try. Conversely, I can send you out there and you get really good at it, but understanding the principles beforehand provides a significant advantage.” The d.School motto sums up this complementary relationship: “Do to think. And think to do.”

***

Taha credits design thinking courses for completely changing her outlook on learning. “A lot of [other] classes are: Here's a book. Read it. Here's a prompt. Write it. We are constrained to the context of where the assignment is versus the world we live in,” she says. But her work in d.school classes felt practical and applicable to everyday life.

In an advanced product design course, Target challenged Taha and her classmates to develop a smart product for the "Internet of Things" market. As a target audience, the group chose mothers who work from home. After visiting many moms in their workspaces and determining key areas of need, they developed lighting that changed to shift a space from home to work mode, so that moms could have a physical marker that helped them transition between the two.

During this project, Taha says the students were told there were no limits to what they could propose—even if the technology for the product didn’t exist yet. “If you’re not restricted, you become a lot more creative," she says.

***

In innovation courses, there is no existing answer to the questions being discussed. “We never tell students we have the answer. We keep asking them questions and push them to overcome them,” says Sutton. “Instead of lecturing as a professor, I stop and have students brainstorm solutions.”

Learning in this type of environment changes the way that students approach problems post-graduation. “It’s about being entrepreneurial in how you live your life,” says Greene. These students don’t trip up when faced with a problem—they question, poke and probe until they figure out a solution.

“I never thought of myself as creative or entrepreneurial, but classes at Stanford pushed us to do, and when you go through that process, you realize your own potential," says Patel. Now on the market, his infant warmer has impacted the lives of about 200,000 babies in 12 countries. "Not only did this all start as a class project, but it's the empowering educational experiences we had at Stanford that gave us the ability and confidence to take the dive, move to India and build the company, despite the many challenges we faced," he says.

Companies recruiting across industries specifically seek out students who have taken design-thinking courses. According to a survey by the Association of American Colleges and Universities, employers, more than anything else, look for college students who have had “educational experiences that teach them how to solve problems with people whose views are different than their own.”

***

Taha is now working as a design thinking strategist at Capital One Labs in San Francisco. She says her time spent at the d.school has had a major impact on her choice of job and how she aims to approach her work.

“I want to be solving real people's problems. I don't want to work in an organization that goes 18 months without ever being tested in front of a real user," she says.

“College can help you understand what your cause is," Taha adds. "Once you understand it, now what are you going to do with it?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/profile.jpg)