How Pyrex Reinvented Glass For a New Age

One hundred years after the birth of the brand, the Corning Museum of Glass pays homage to America’s favorite dish

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/52/87/52872d2c-b698-446f-a01d-1244a3141703/pyrex-main.jpg)

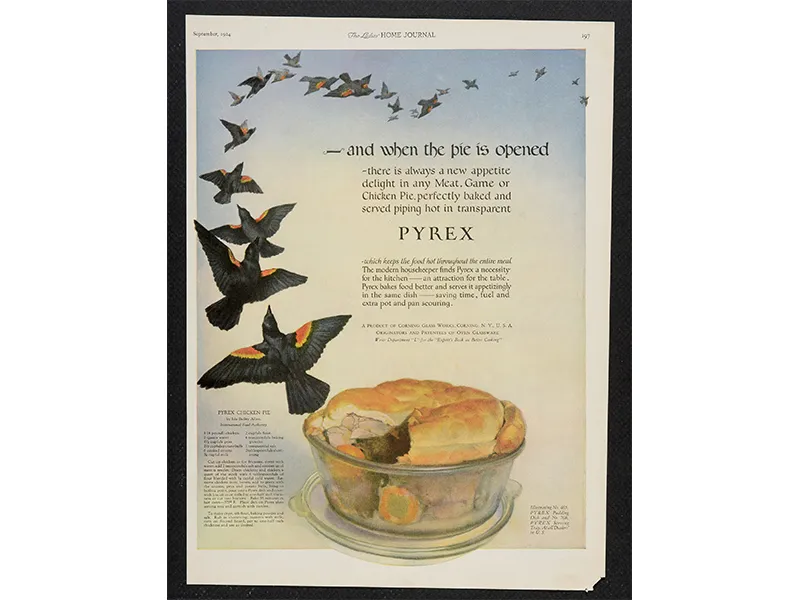

The story of Pyrex glass began like most inventions do: with a problem. Bessie Littleton's earthenware casserole dish had cracked. It was 1914 and Littleton's husband, Jesse, was working as a physicist at Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated) in Corning, New York, where he was evaluating the company's formula for temperature-resistant glass for use in railroad lanterns and battery jars. Bessie asked her husband if the glass might work for baking, so he sawed off part of a battery jar and took it home to her. With this makeshift dish, Bessie successfully baked a cake and her experiments, in part, moved Corning to launch Pyrex, the first-ever consumer cooking products made with temperature-resistant glass, in 1915.

One hundred years later, the Corning Museum of Glass—a private, non-profit foundation supported in large part by Corning Incorporated—is looking back at the history of Pyrex with an exhibit, "America's Favorite Dish: Celebrating a Century of Pyrex," which opens on June 6.

"Pyrex was an amazing innovation," says Bret Smith, professor of industrial design at Auburn University. "It made people reexamine how they thought about glass, and it fueled an interest in more durable materials. Glass became part of a new age of materials, and durable glass came to be used in so many things, from percolators to windshields."

Corning Glass Works wasn't the first company to develop temperature-resistant glass, however. In the 1880s, a German scientist, Otto Schott, developed a low-expansion glass called borosilicate glass, but used it mostly to make products for industrial and scientific settings, such as laboratory glass. Corning developed its own recipe in 1908, mostly selling it to railroad companies for signal lanterns. The company was interested in marketing the glass to household consumers, and Bessie Littleton’s cooking experiments opened up a world of consumer applications. Corning held a patent for its formula for borosilicate glass from 1915 until 1936; when the patent expired, the company came up with a new formula for heat-resistant glass, alumino-silicate glass.

Company accounts suggest that the name Pyrex came from the company's tradition of using "ex" in its glass formulas (Corning's first heat-resistant glass was called Nonex), according to Regan Brumagen, public services librarian and co-curator of the exhibition at the Corning Museum of Glass. She adds that the company was probably also playing with the prefix "pyro," as early ads had the words "fire-glass" printed beneath Pyrex.

Early products included the typical Pyrex casserole dishes, as well as pie plates, shirred egg dishes, custard cups, loaf pans, oval baking dishes, cut-glass teapots and engraved dishes. In 1925, the Pyrex liquid measuring cup was introduced, though it didn't look like the one commonly used today (it had two spouts on opposite sides, with a handle in between).

Victoria Matranga, author of America at Home: A Celebration of 20th Century Housewares and design programs coordinator at the International Housewares Association, notes how well the early designs have held up: "The measuring cup and the oblong and square bakers are truly iconic."

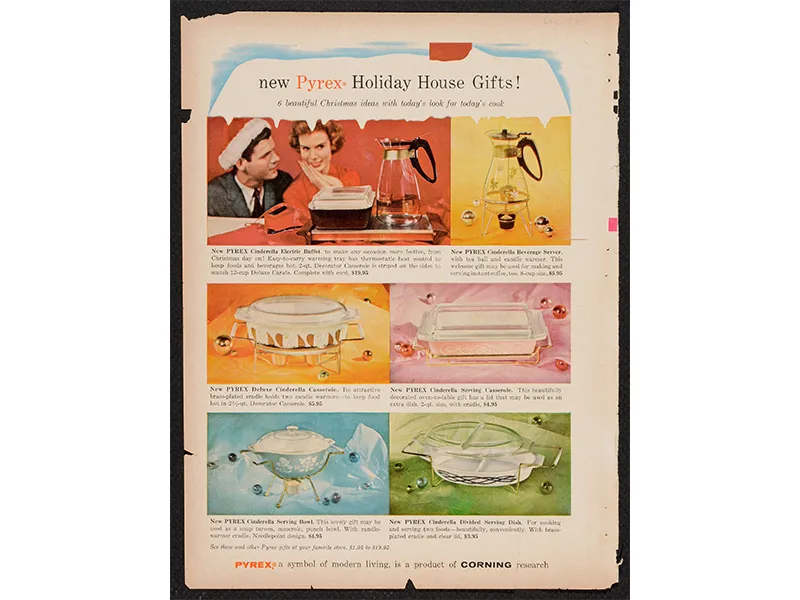

But Pyrex wasn't an overnight sensation. The products were expensive; the production process was initially just semi-automated—meaning the machines were still manned by factory workers. An early advertisement shows a maid, not a housewife, using Pyrex, indicating who Corning felt was the ideal market for the cookware. Pyrex could withstand the heat of the oven as well as the cold of the refrigerator, but in the '20s, only well-off families had homes wired for electricity and refrigerators were considered a luxury.

After World War I, home economics was emerging as a profession, and many women were earning college degrees in this progressive, multidisciplinary field, which applied the principles of science to homes, communities and families. This training prepared women for jobs in academia, public education, industry and government. Corning, like other companies, used the trend to its advantage, hiring domestic professionals to test and promote its products. In 1929, Corning hired a full-time scientist and home economist, Lucy Maltby. In the years that followed, Maltby established a test kitchen to evaluate new products and became an advocate for the consumers who used Pyrex, fielding thousands of letters. Maltby and her test kitchen team "had a profound impact on the functional design of Pyrex products," Brumagen says. Maltby first convinced the company to redesign its cake pans, adding handles and volume, and making the diameter smaller so that two cake pans could fit side-by-side in a standard oven. Maltby's influence was so strong that Corning executives had a mantra: "What does Lucy think?"

"As time has gone on, women have become more discriminating," Maltby once said. "It has become even more important to have home economists work with designers and product engineers." She saw her role as "looking with new eyes on the ever-changing patterns of living."

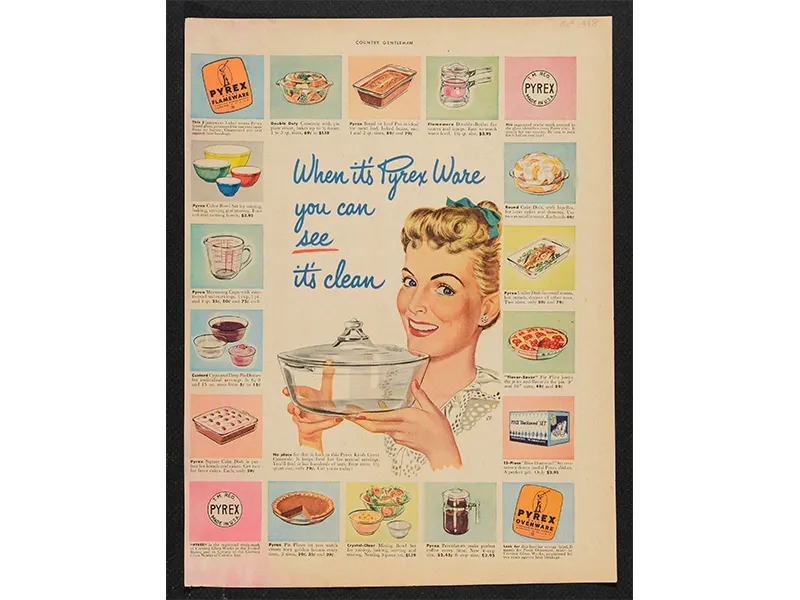

In the '30s, Pyrex became affordable for the masses, when the production process became fully automated. It's remarkable how quickly Corning was able to make the products affordable for a larger audience, Smith says; within roughly 15 years, the products had made their way into the kitchens of farmers and city folk alike. Corning also introduced a line of stovetop pans called Flameware in the '30s. Juliet Kinchin, curator of modern design at the Museum of Modern Art, says the glass frying pans produced during that period "have a certain shock value. It's one thing to put a casserole dish in the oven, but putting glass in direct contact with heat was an uncomfortable idea." Flameware, which was later sold under different names, was on the market until 1979. It was eventually discontinued, as Corning came out with more popular products.

Part of the home economics movement was the idea of food safety and keeping a kitchen sanitary. Pyrex appealed because of its clean look and the ability to see the food inside. An early Pyrex ad shows a secretary at Corning Glass Works clad in a laboratory-style all-white outfit, looking through a pie plate.

Pyrex was also literally cleaner: Smells didn't cling to or seep into the glass the way they did with ceramic, earthenware, cast iron and tin, and the glass didn't rust. Efficiency was also part of the home economics movement, and Pyrex dishes, marketed as being able to cook food quicker, meant that women could save time and fuel.

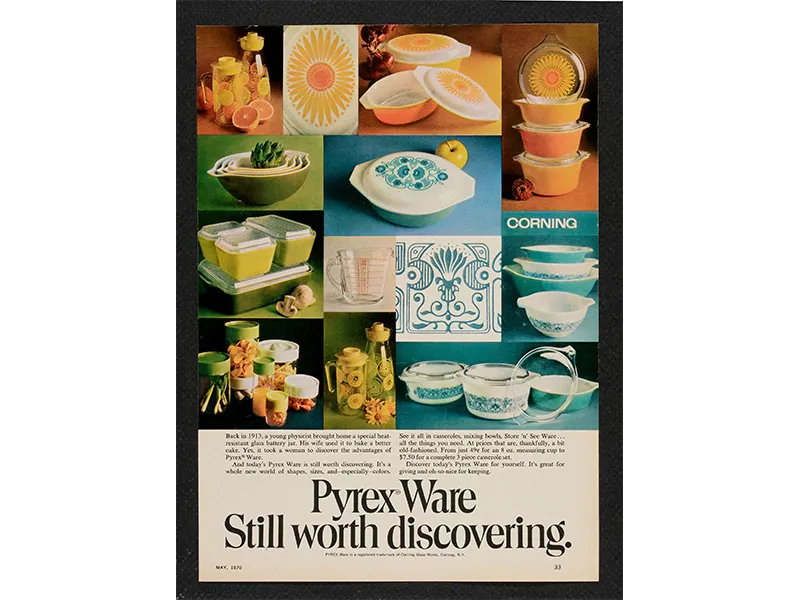

Pyrex's efficient cooking, its material and domestic manufacturing made it indispensable during World War II, when families were instructed to conserve energy, metal was scarce and glass imports from Germany were cut off. During World War II, ads emphasized that using Pyrex was patriotic; one read, "My wife sure makes food fight for freedom!" Corning developed a line of durable military mess ware, and post-war the line evolved into opalware—an opaque glass. Over the following decades, Corning would apply color and decorative patterns to opalware, creating more than 150 distinct designs.

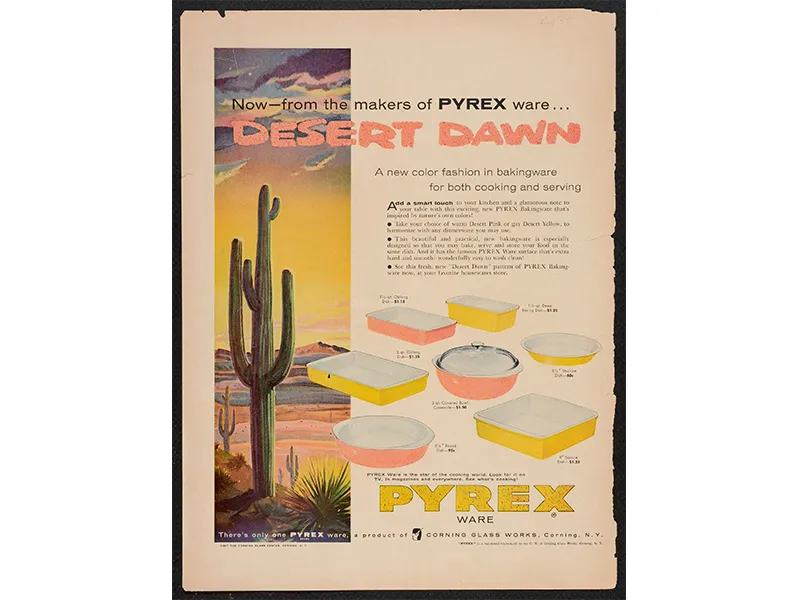

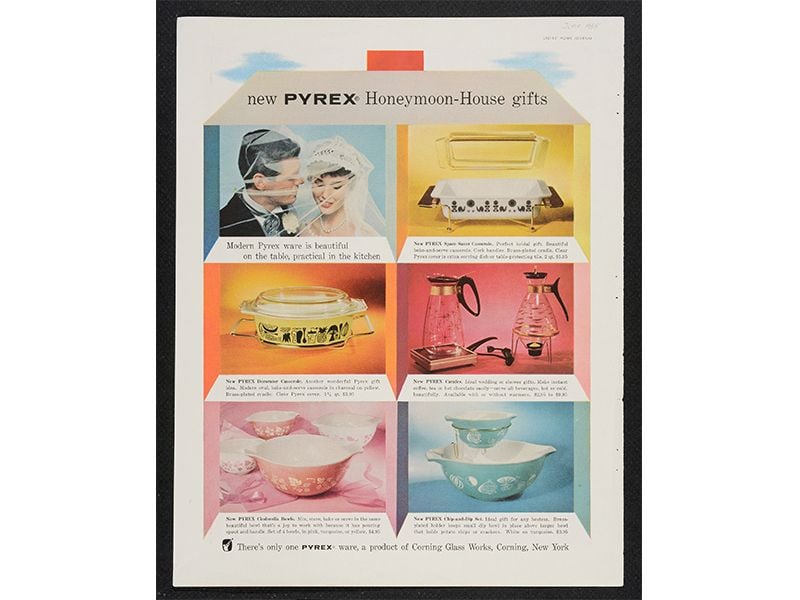

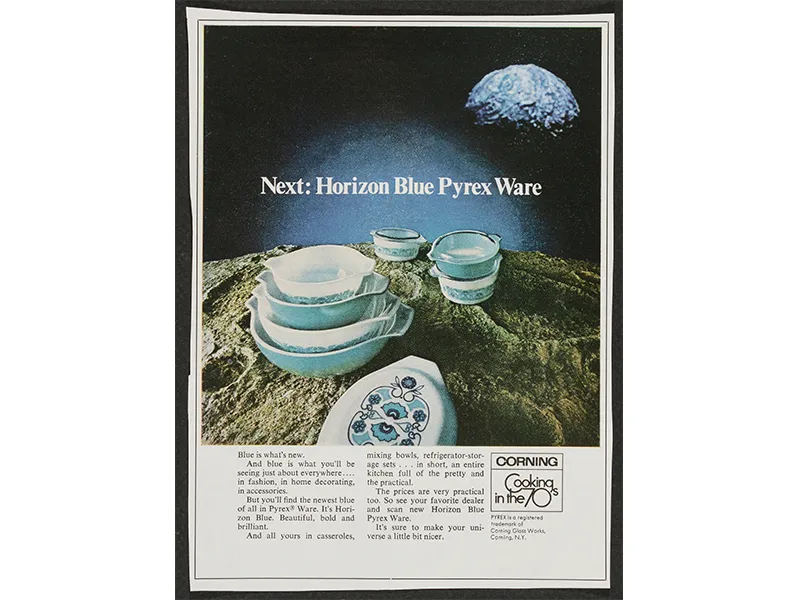

"In the post-war period, you have this explosion of color in the kitchen, with plastics and other materials, and the mixing and matching of colors in tableware," Kinchin says. "That's also when the barrier between the kitchen and other spaces broke down; the kitchen became a communal space. With new, spacious kitchen designs, dishes were on view for all to see. With colored Pyrex came the oven-to-table idea, which had always existed but was adopted by wealthier households after the war."

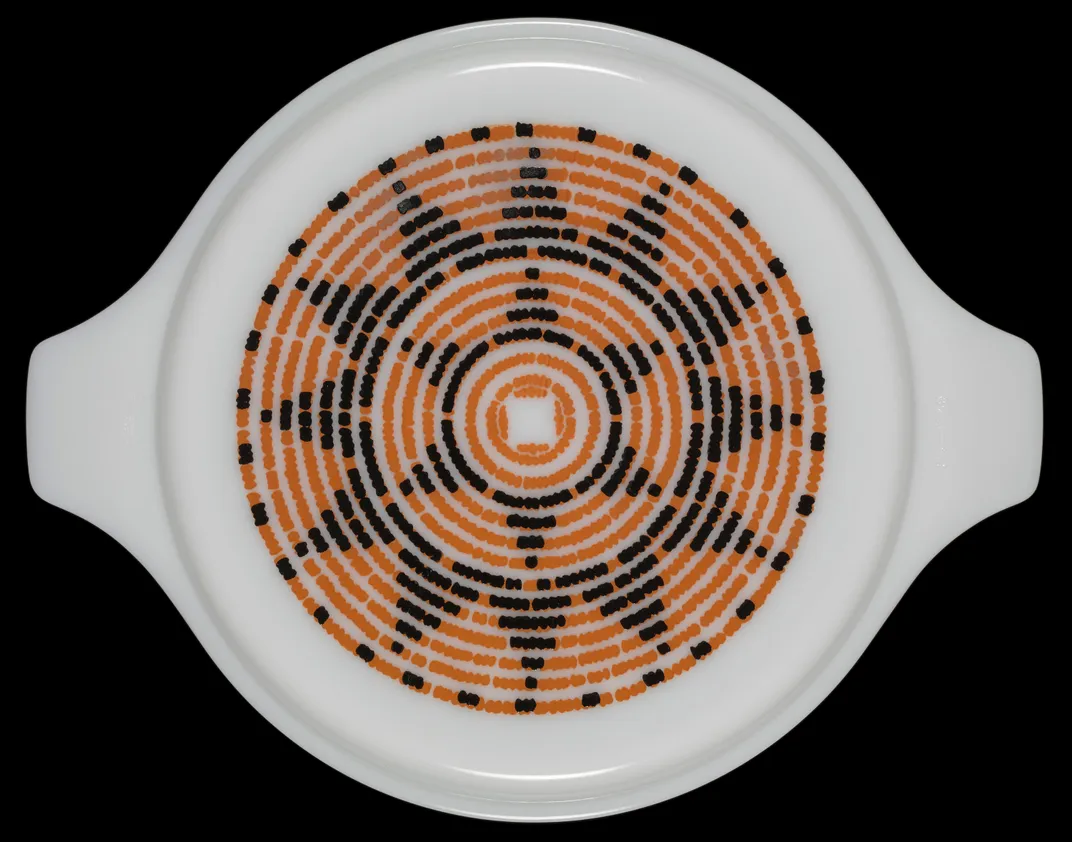

Most people associate Pyrex with brightly colored pieces from the '50s; turquoise pieces—such as ones with the "Butterprint" pattern, depicting an Amish farming couple—and pink pieces, are especially popular with collectors. In the '60s, the tones became earthy and muted, as in the "Terra" pattern, characterized by a black exterior and simple, thin rings of brown. The Corning Museum of Glass exhibit includes advertisements, ephemera and a wide variety of products from the brand's history: everything from an elegant cut-glass teapot from the '30s to casserole dishes in psychedelic hues from the '70s. In a large atrium, a long wall is filled with row after row of opalware patterns—nearly 150 in total—in a crazy rainbow of colors.

"There's an astounding variety of colors and designs, and you can pick out the decades so clearly. For instance, there's a '70s avocado green that I recognize from my parents' kitchen," Brumagen says.

Colors and styles may have changed, but temperature-resistant glass stood the test of time. In the '70s and '80s, Pyrex only became more relevant as microwaves were adopted. Originally, there was an incredible variety of sizes and styles of Pyrex dishes, Brumagen says; there were more than 100 styles according to a 1919 ad. Now, some of the same products are produced, but with less variation. Transparent ovenware, especially, has not changed much over the years.

But Pyrex's history is not without controversy. Around the '50s, Corning began making Pyrex out of thermally tempered soda-lime glass, which is less expensive to produce, instead of borosilicate glass. Other companies are still using borosilicate; in fact, Pyrex that's produced in Europe is still made using borosilicate glass. In recent years, Consumer Reports has documented hundreds of cases of Pyrex dishes shattering and injuring users, but the magazine's tests have been inconclusive. It has called for the Consumer Product Safety Commission to investigate the glass bakeware on the market, comparing soda-lime glass and borosilicate. World Kitchen, which has owned the Pyrex brand since 1998, claims that the tempered soda-lime glass is as durable as borosilicate and very safe, and that the incidents reported represent only a fraction of one percent of the millions of households that use Pyrex products. World Kitchen's website instructs users of Pyrex ovenware to avoid severe hot-to-cold temperature changes and, when dealing with a hot dish, avoid placing it or its cover in the sink, adding liquid, immersing the dish in water or placing on wet or cold surfaces.

Criticism aside, it's unusual to find an American kitchen that doesn't include at least one Pyrex product. To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the brand, World Kitchen unveiled the world's largest measuring cup—standing four feet, two inches tall and capable of holding 3,040 cups—at the International Home & Housewares Show earlier this year. It will be on tour this summer throughout the country.