How Solar-Powered Recycled Smartphones Could Save the Rainforest

A Silicon Valley non-profit is ready to give the forests of Africa and the Amazon ears to listen for loggers—and the ability to phone the authorities

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/30/a6/30a6dc8f-d27e-4949-af33-e00015478320/phone_solar_petal2.jpg)

With short, incessant upgrade cycles and a reliance on rare earth elements and low-wage labor, smartphones often get pegged as a problem, both for the environment, and for the people in developing nations where their components are mined and manufactured.

But Silicon Valley physicist and engineer Topher White, founder of the non-profit Rainforest Connection, thinks our discarded tech can be repurposed to do some serious good.

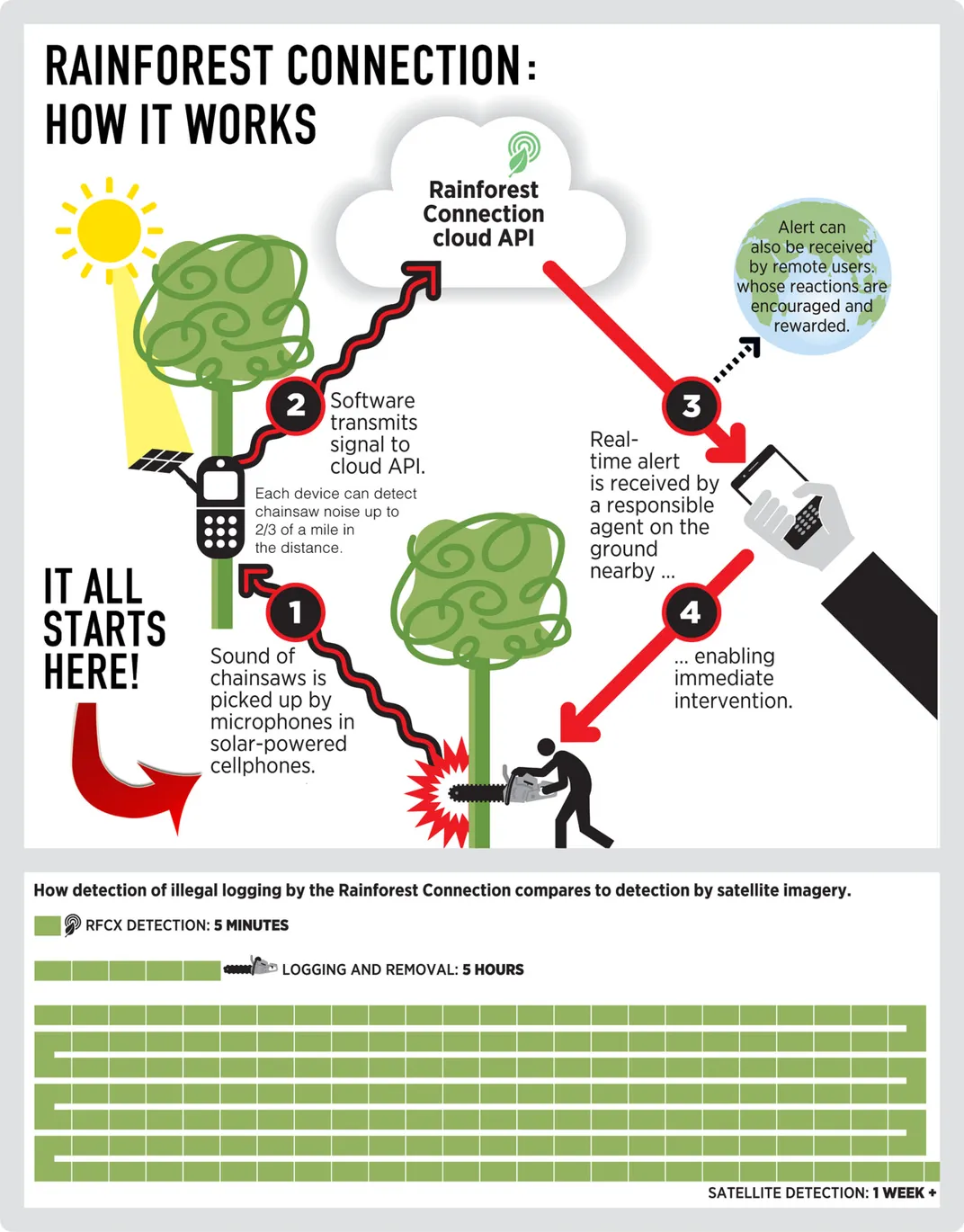

The idea in a nutshell is to place solar-powered phones high up in the tree canopy where they’re tough to spot, but they can listen in for the sounds of chainsaws (and eventually vehicles and poachers). When they detect the sounds of illegal activity, the hidden phones use existing GSM cellphone networks to alert authorities of the location in real time, so that the authorities can deploy to the area and stop the loggers before they fell too many trees. According to the group, each phone can protect up to one square mile of forest.

The technology arguably comes at a crucial time for the future of many forest conservation efforts, with recent studies showing places like Borneo losing nearly a third of its rainforests in the last 40 years. While the problems of illegal logging have been well known for years, existing techniques for stopping deforestation are either too slow (satellite imagery is mostly used to survey damage after the fact), or too expensive (aircraft can fly over the forests, but can’t cover huge areas without great expense).

Rainforest Connection has already tested the technology in a limited run in Sumatra in 2013, where White says their devices detected loggers within two weeks. The group, along with local conservationists, was able to deploy to the area and interrupt the logging.

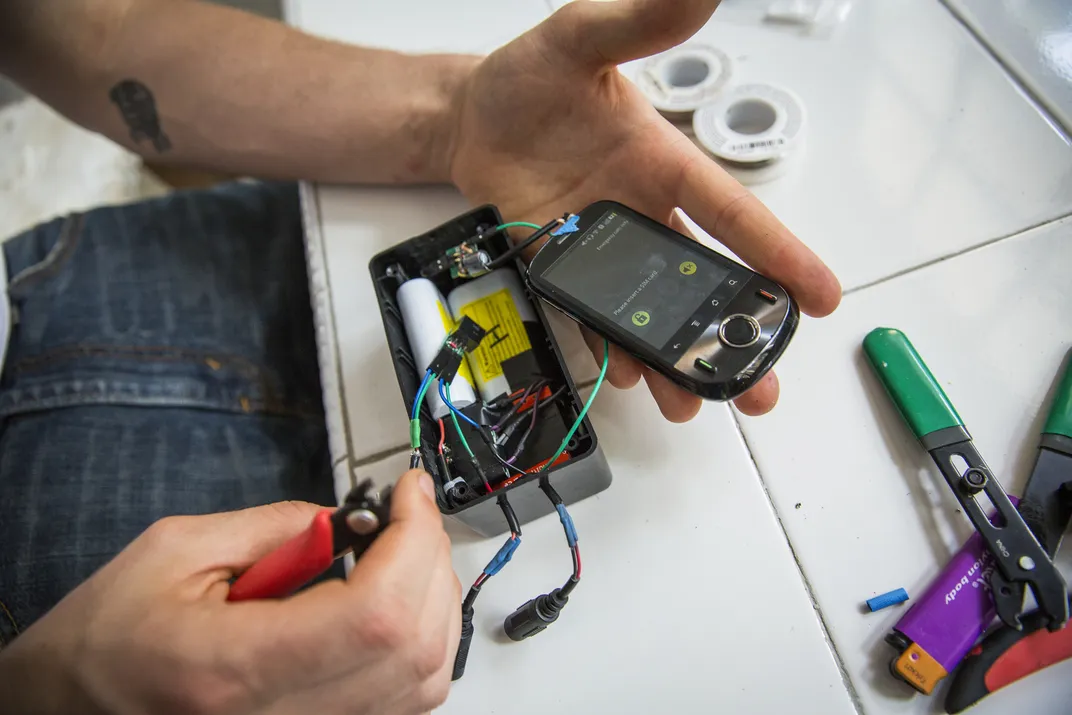

Before White and Rainforest Connection got to that first milestone, they faced several challenges. The core idea of the setup is simple enough. Attach a phone high up in a tree where it can get the best cell reception. Then add another phone in another tree a certain distance away (rougly one every square mile), and continue the process until the network of smartphones covers the area. When a phone detects the sound of a chansaw, it sends an alert that includes its location, so authorities can respond quickly.

White says cell networks are good enough in most areas for the phones to remain connected. Many developing nations have embraced mobile phone technology because it's less expensive to set up and maintain than traditional landlines.

Providing enough power proved to be an issue, however. The tree canopy, with its bursts of intense light and shade, is far from the ideal place to harness solar energy. So White had to do some testing to find out what would work.

“The petal [design] that you see [in our images] is able to maximize the amount of power that comes out of these rays of light and sunflecks that are able to make it through the canopy,” says White. “But the flip side is that they’re much less efficient than a normal solar panel, so we have to have more of them.”

Dealing with the cellphone payment plans of other countries was also a problem White says he ran into in Sumatra. “The biggest adaptation that I had to make in the field,” says White, “was teaching the phones to top each other up and deal with the quirks of the network out there in Indonesia versus here in the United States.”

Next Up: Trials in Africa and South America

Now, Rainforest Connection, partnered with the Zoological Society of London and fresh off a successful Kickstarter campaign which raised $167,000, is ready to test its technology on a broader scale in Africa and the Amazon over the next year.

The group will be working with local law enforcement and conservation groups to teach them how to set up, install and manage the ad hoc network of smartphone-outfitted trees. Eventual autonomy from Rainforest Connection will be an important step. Many technologies intended for remote areas fail because there’s no one around to repair or replace them when something goes wrong. White says that it’s unclear how long the devices will keep functioning in the treetops, but he suspects most will run for a year or two at least. And it’s doubtful the supply of discarded phones will run out anytime soon.

The Kickstarter funding will pay in part for refined specialized housings for the phones and solar panels, which should make them less expensive, easier to deploy and better able to stand up to the elements. The group also plans to create an app that will let anyone in the world listen to the sounds of the rainforest at any time, and receive alerts from the trees in real time.

White says the initial idea wasn’t to use smartphones at all, but to create customized hardware that would interact with cellphone networks. But smartphones, which are loaded with sensors, already tested to stand up to wear and tear, and built around an established development platform, proved too appealing to ignore—especially since millions of still-functioning models are discarded every year.

Beyond the hardware: Engagement and eventual monetization

The notion of setting up a surveillance network over vast swaths of pristine forest sounds a bit sinister. But, the idea of using old smartphones is perhaps as much a clever public relations move as it is a prudent use of discarded technology. White says an app that lets users in other countries listen in on the forest and take part in the monitoring is also essential to get people to reengage in rainforest issues.

“The messaging hasn’t changed in 20 years,” says White. “Because 20 years ago it was an incredibly urgent, destructive, terrible issue. Here we are 20 years later, and it’s perhaps worse. But it’s still just as distant and just as abstract. There’s been a general decline in people’s feelings of urgency.”

As the project moves forward, Rainforest Connection hopes to expand the scope of the project so that the phones can detect things like vehicle use in off-peak hours, and the sounds of potential poachers. In Africa, they also want to see if the technology can be used to track elephants through the forest.

But in the long run, White thinks the real solution is not in stopping illegal activities, but in showing locals that they can make money from the rainforest in non-destructive ways. And on that front, White’s ideas sound straight out of Silicon Valley.

“Impressions can be monetizable. People care about the rainforest, but there’s not a lot of engaging content coming out of it,” says White. “If you’re able to make people pay attention and integrate [the rainforest] into their everyday lives, the fact that people pay attention can be used to generate revenue for the people.”

Can information and interest alone keep an economy growing and deter a handful of people from exploiting the environment in destructive ways? That question is just as pertinent to the asphalt jungles of New York and San Francisco as it is to the remote rainforests of Africa, Asia and South America.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)