How the U.S. Postal Service Could Tackle Food Insecurity

A team of Washington University students has a plan: use postal workers to pick up food, deliver it to food banks and even store it in post offices

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/c3/e8c334f6-b252-4aae-b976-18e5605c7a40/screen_shot_2017-01-26_at_45916_pm.png)

If you’re an avid podcast listener, you’ve probably heard the pitch for Stamps.com, a website where users pay for and print postage from their own computers: “You’ll never have to go to the post office again.”

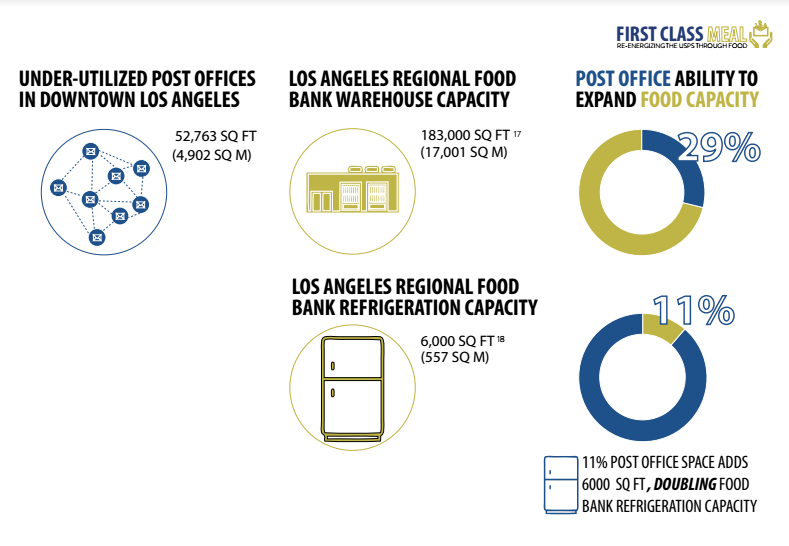

For many, as UPS, FedEx and Amazon have encroached on United States Postal Service turf and communication has gone digital, that’s already a reality. Since 2006, according to the USPS’s own numbers, revenues are down, employment is down, total mail volume is down and post office visits are declining. As a result, thousands of branches have closed or slashed hours over the past decade. Yet the buildings remain, and so does the postal delivery infrastructure.

Anu Samarajiva, Irum Javed, and Lanxi Zhang, students at Washington University and winners of the recent Urban SOS competition by engineering firm AECOM and urban design nonprofit Van Alen Institute, see that as an opportunity. The annual competition, which invites students to take on a global infrastructure challenge, focused this year on “Fair Share” and the so-called “sharing economy,” defined as using digital platforms to connect those with resources to those without. How, the proposal asked, could applying sharing economy principles to infrastructure support a more equitable distribution of public goods?

“The most obvious critique of the shared economy is that it really improves the life of a small portion of our population,” says Stephen Engblom, senior vice president and global director of AECOM Cities. “It helps the wealthy, but it doesn’t really help the challenged sectors of our populations.”

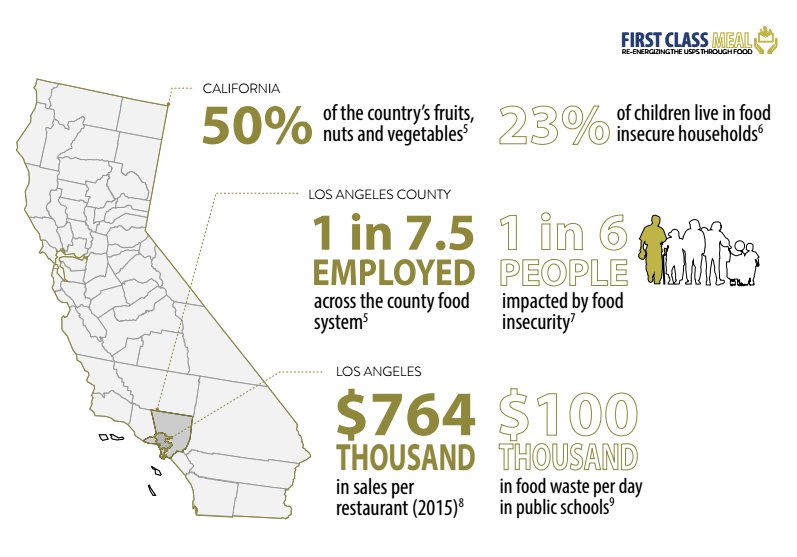

The winning proposal, First Class Meal, posited that post offices could remain relevant in a digital world by providing delivery and logistics for one of Los Angeles’ most pressing needs: food insecurity. Samarajiva had been in an L.A.-focused design studio, and along with Zhang and Javed, a public health student, was interested in food policy. Talking to food banks and other organizations battling urban hunger, they learned that while there is no lack of wasted food in the L.A. area, organizations struggle to pick up donations, store them and distribute to people in need.

“We kind of had this realization that the post office still touches us all,” says Samarajiva. “It has this incredible network and connection to all of us as citizens, but it’s just what is it delivering now, how is it connecting us now?”

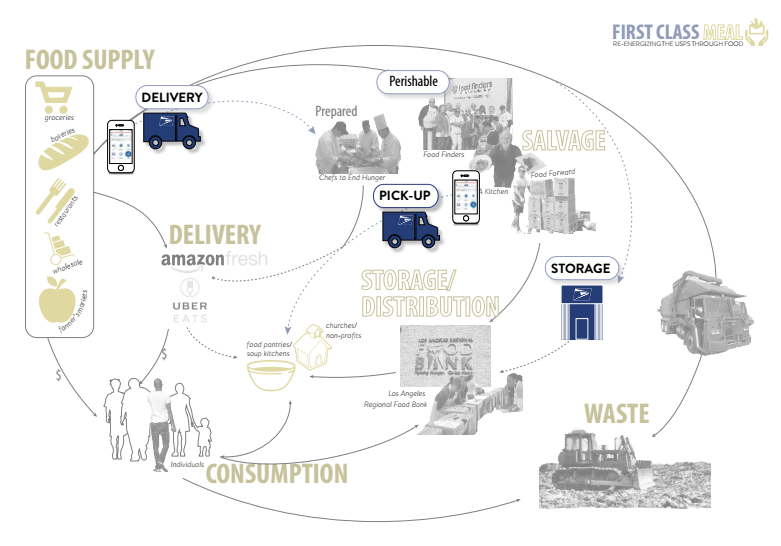

In the First Class Meal proposal, USPS would connect interested organizations. Postal drivers out on their normal routes would pick up donations of food from groups that collect them, deliver to food banks or pantries, and store food in post offices with excess capacity. The existing USPS app would direct drivers to where donations are waiting, just like a customer might use the app to schedule a package pickup today.

“There are already a lot of organizations in a place like L.A. working on remediating food insecurity,” says Samarajiva. “We don’t want to duplicate that work. But we talked to them and realized there are gaps in how they are able to serve people. … The post office infrastructure would be used to fill those gaps.”

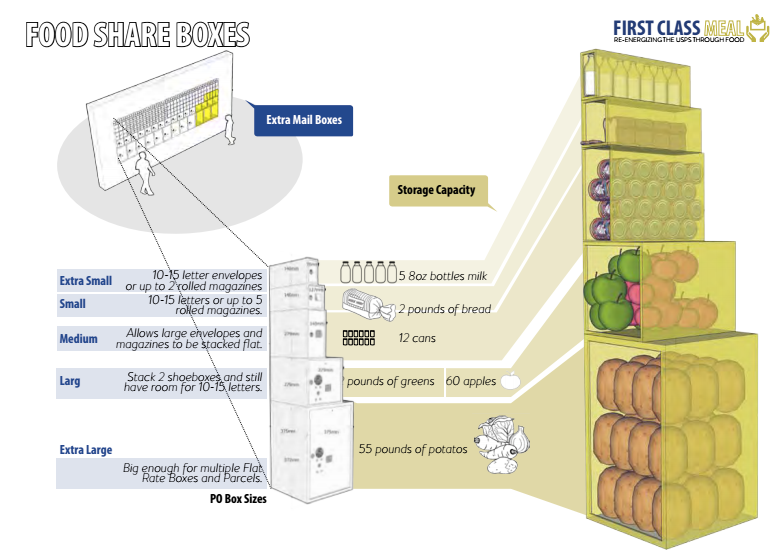

The team also imagined post offices and retrofitted trucks as food share stations. Trucks with cooling technology could go into food deserts as pop-up markets, while also giving residents the opportunity to weigh their mail, and buy postage stamps or food stamps. Or residents could go to the post office to pick up donations. The presentation includes a vision of redesigned post office boxes storing milk, bread, greens and other staples. (Who knew an extra-large P.O. box could contain 55 pounds of potatoes?)

“There is some idea of a stigma with going to a food pantry, but [in this proposal] you’re just going to the post office,” says Samarajiva. “We wanted to normalize the idea because food insecurity is so prevalent.”

At first, she admits, the post office tackling hunger seems an unlikely juxtaposition, but it may be no more of a contradiction than the fact that 1 in 7.5 Los Angeles County residents work in the food system — but 1 in 6 experience food insecurity. In downtown L.A., a number of post offices are in food deserts, some of which, including the pilot location explored in the First Class Meal proposal, operate only on limited hours. Post offices are already expanding their capacity to deliver food in order to accommodate Amazon Fresh, a grocery delivery service.

And, as the students learned, the National Association of Letter Carriers has held America’s largest one-day food drive every year since 1991, a fact that makes many postal workers immensely proud. In 2016, 4,232 L.A. USPS district members alone collected 1,523,525 pounds of food, the second-highest collection rate in the U.S. “This isn’t a venture that’s straying away from their current ventures at USPS,” says Javed.

The proposal sounds like it would strain staff and budgets though, and anyone who has stood in an endless post office line or waited days for a package that never arrived might be wary of heaping the USPS with more responsibility.

The First Class Meal designers say the food share stations in post offices could be staffed by volunteers from food service organizations, and that if the post office is already handling more grocery packages through Amazon Fresh, they can handle the increased load from food donations. They also hope expanding into food access work could shore up USPS branches from further closures, like the nearly 3,700 threatened and then walked back in 2011.

“I think by making them more of a staple in communities, by showing that they’re giving back, by distributing food to people in need, I think it makes a stronger case for the USPS,” says Javed.

So far, the USPS’s L.A. office has not officially commented on the plan. But by chance, L.A.’s director of planning and chief resilience officer were both jurors for the final competition, which was hosted in L.A., and both expressed interest in learning more, says Samarajiva.

And whether or not it’s implemented, the competition’s framing and finalists do shine a light on the inequity of most existing sharing economy platforms, and their unrealized potential. In October, two weeks after the Urban SOS semifinalists were announced, three drivers for Amazon Flex, an Uber-like delivery pilot for the logistics giant, filed a lawsuit saying they should be treated as employees rather than independent contractors.

Other finalists included an app that connects households in Durban with paid informal waste collectors and a project to map the needs and resources of residents in Quito’s self-governing indigenous territories in a bid to help them work more collectively.

Jen Kinney is a freelance writer and documentary photographer. Her work has also appeared in Satellite Magazine, High Country News online, and the Anchorage Press. See her work at jakinney.com.

This story was originally published on NextCity.org, which publishes daily news and analysis on cities. Learn more about Next City by following them on Twitter and Facebook.