How You Wound Up Playing ‘The Oregon Trail’ in Computer Class

From the 1970s to 1990s, the government-owned Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium dominated the educational software market with more than 300 games

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/42/54/4254a590-f18f-4cde-b772-64a2043f1610/the-oregon-trail.jpg)

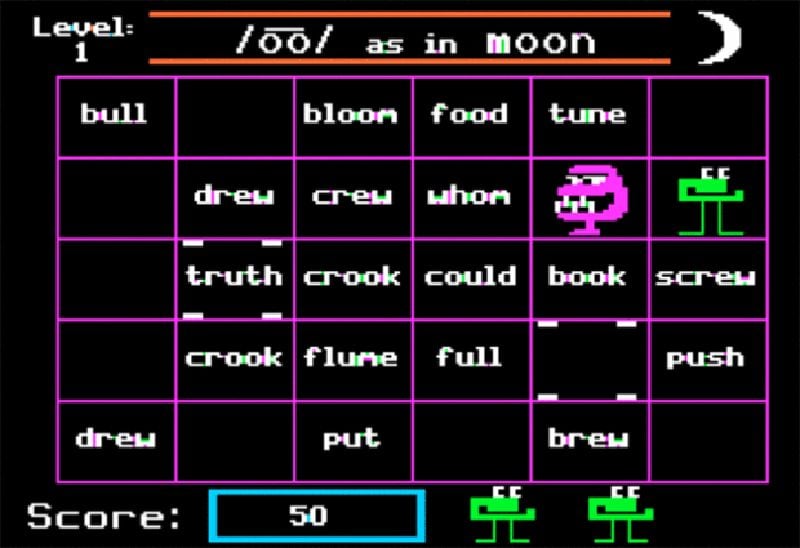

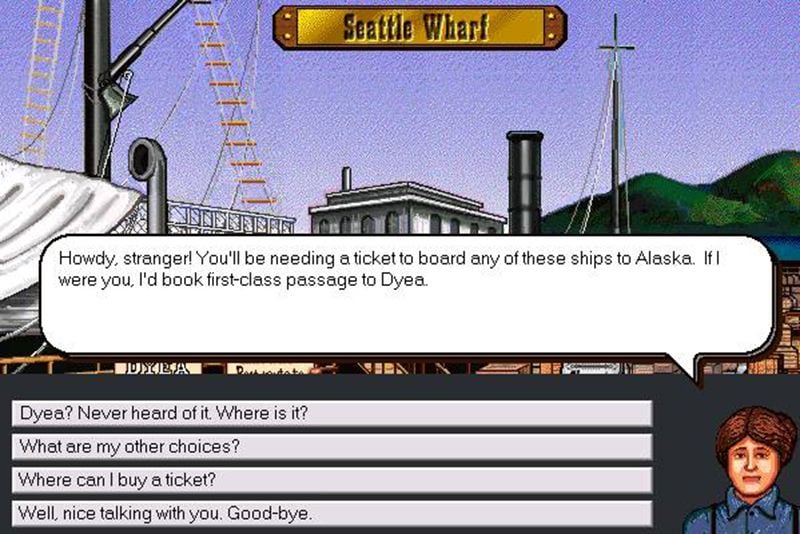

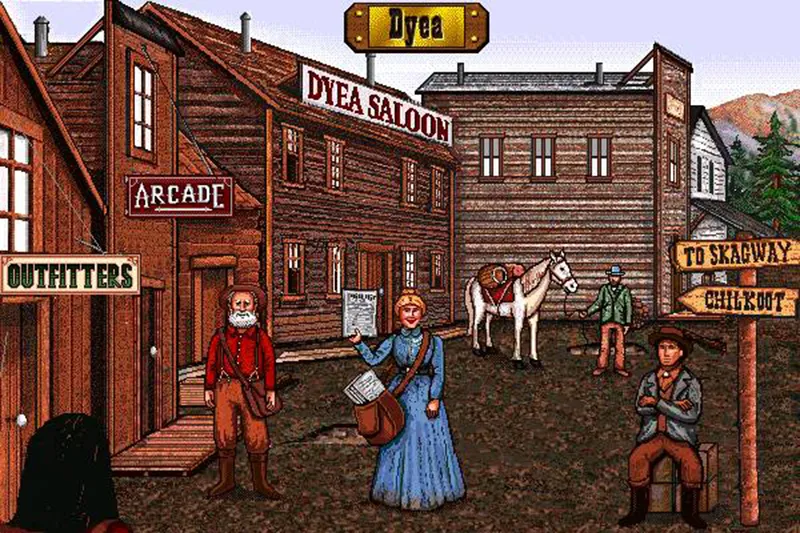

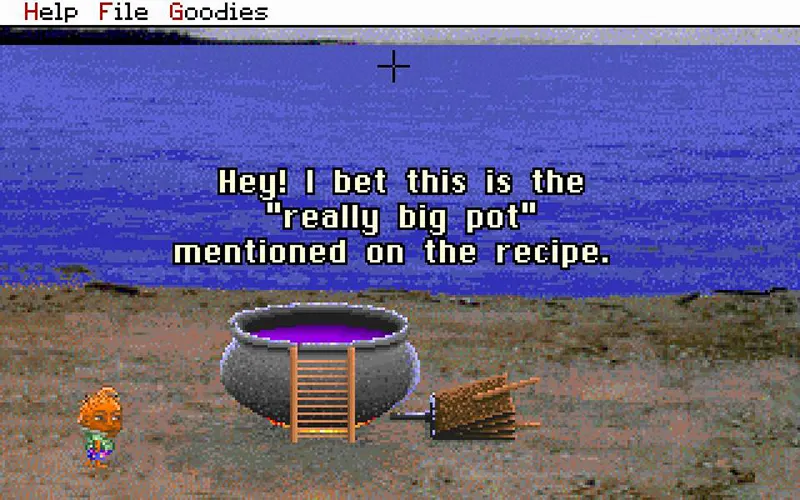

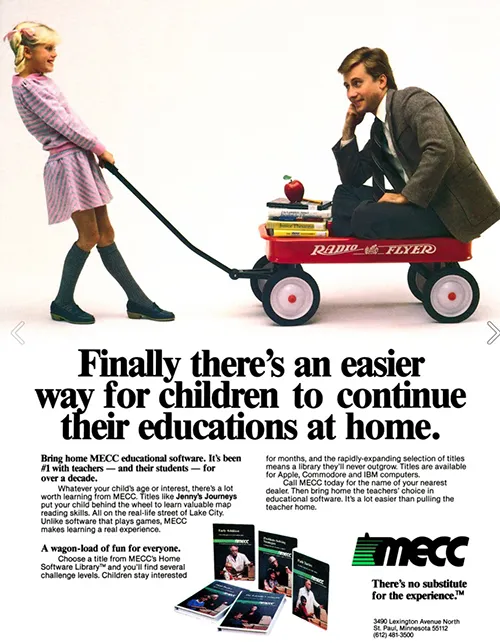

The Oregon Trail, The Yukon Trail, Number Munchers, Word Munchers, The Secret Island of Dr. Quandary, Lemonade Stand, DinoPark Tycoon, Storybook Weaver. All games you played in school, all made by the same state-funded company—the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. Never heard of MECC? It went hand in hand with Apple Computer Inc. in its earliest days. Steve Jobs said as much in a 1995 interview with the Smithsonian Institution: “One of the things that built Apple II's was schools buying Apple II's.” Apple II's loaded with MECC games.

Minnesota was a Midwestern Silicon Valley by the early 1970s. The State of Minnesota threw huge funds to entice computer programmers to Minneapolis and Saint Paul when it created MECC in 1973. From 1978 to 1999, MECC, together with Apple, competed against private software companies to turn American children into a nation of computer-savvy early adopters and make computer class as much a part of American schooling as math and English.

“MECC’s goal was on putting a computer in the hands of every K-12 student in Minnesota,” says Dale LaFrenz, MECC co-founder and CEO from 1985 to 1996. “We already had all schools in Minnesota running teletypewriters hooked to a huge UNIVAC [mainframe].” The UNIVAC was installed in a climate-controlled room at MECC headquarters. Up to 435 users across Minnesota could access it at one time from anywhere that had a telephone line.

Once MECC had this system, it needed a game.

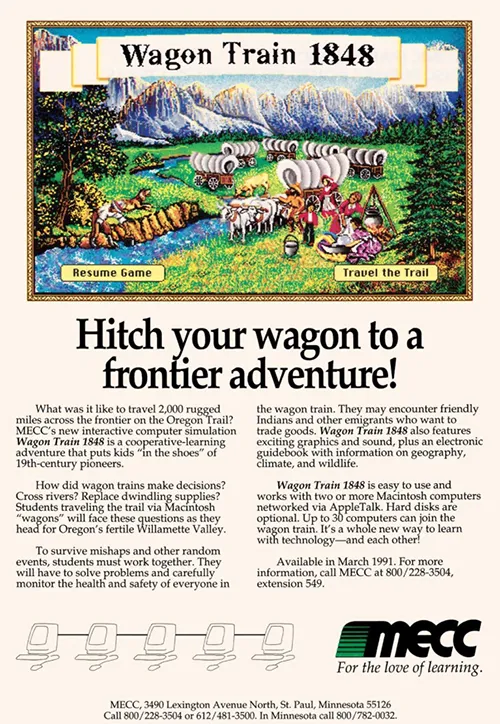

Don Rawitsch, Bill Heinemann and Paul Dillenberger, three student teachers enrolled at nearby Carleton College, created The Oregon Trail in November 1971 for an eighth-grade history class Rawitsch was teaching. The game starts in Missouri, 1848, where the player equips a party of pioneers for the 2,000-mile journey to Willamette Valley, Oregon. Along the way the player manages his or her wagon train through river crossings, food shortages, injuries, illnesses, breakdowns and theft. As soon as Rawitsch uploaded it to the UNIVAC mainframe it became a hit. Then he deleted it. His class finished in December. “We had to remove the game from the Minneapolis Schools computer,” says Rawitsch, “and we had no other computer to run it on. We printed on paper the entire listing of the programming code for the game.” The Oregon Trail was only a month old.

When MECC hired Rawitsch in 1974, the game had been a dormant pile of papers for three years. MECC set him to work resurrecting the game, and as he did, he added new features. He read diaries of Oregon Trail pioneers for ideas on new events to include, such as pegging the likelihood of certain events to certain locations. “For example, the South Pass through the Rockies occurs at 950 miles along the trail,” he says. “Only if (you were at least 950 miles along) would certain mountain-related events like 'snow' or 'oxen injury in rough terrain' occur.” Accounts of help from American Indians popped up often in those diaries, so he introduced events into the game where players would encounter friendly tribes. “I sharpened up the historical accuracy of the game without changing its design.” The revised The Oregon Trail landed on Minnesota's UNIVAC system in 1975, right about the time companies were preparing the earliest (relatively) small and affordable personal computers.

“When the first personal computers hit the market—Apple II, Tandy TRS-80, Commodore Pet—MECC realized that it wouldn’t take long for schools to adopt them,” says Rawitsch. In 1978, MECC's product development team retooled The Oregon Trail for the color-screen Apple II released a year earlier. The company had a hunch the personal computer was going to move the education system away from the mainframe.

“MECC went to Apple very early on and cut a deal for five Apple II's,” says LaFrenz. “We launched The Oregon Trail for proof of concept, tested with Minnesota schools and had a positive evaluation.” From there, MECC put out a solicitation for a hardware company to supply the computers. A dozen or so manufacturers answered, among them Radio Shack, IBM, Atari, Commodore and Apple. Apple was an industry lightweight, but Steve Jobs had parallel ideas about computer education.

“[The partnership] worked,” LaFrenz says. “MECC became Apple’s largest dealer and sold to all the Minnesota schools. MECC and Apple were always in sync, including a grand plan to 'save the world by putting computing power in the hands of every kid in America.' Humility did not run in the veins of Steve [Wozniak] and Steve [Jobs].”

“There were about only 10 percent of [American] schools that even had one computer in them in 1979,” said Jobs, in the 1995 interview. “We saw the rate at which this was happening and the rate at which the school bureaucracies were deciding to buy computers for the schools, and it was real slow. We realized that a whole generation of kids was going to go through school before they even got their first computer, so we thought the kids can't wait.”

Minnesota was set, but MECC and Apple wanted the country. “We found a common vision about computing and kids and education,” says LaFrenz.

All MECC games had to do four things, says Rawitsch. First, the information based on real events had to be historically accurate. Second, learning couldn't be spread out in patches; it had to be woven throughout the game start to finish. Third, it had to include thorough documentation for the teachers to use it as a teaching aid. And fourth, the games had to be fun.

“MECC’s focus on integrating technology into the teaching and learning process was the way to promote systemic change,” says LaFrenz. “Remember, the K-12 system is far-flung across a huge continent with millions of individuals involved. All this under 'local control.'”

In his 1995 interview, Jobs spoke of a federal tax deduction he found in 1979. A company that donated scientific equipment, such as a computer, to a university for research and education could write it off as an extra tax deduction. The company would still lose money, but not much. Jobs wanted to apply the rule to K-8 schools and remove the research requirement to allow the tax deduction for exclusively educational purposes. He got a senator and a representative to introduce the modified bill to Congress. The bill failed, but the State of California was enamored. It passed its own version as a statewide tax credit. “We gave away 10,000 computers in California,” said Jobs in the aforementioned interview. “We got a whole bunch of the software companies to give away software. We trained teachers for free and monitored this thing over the next few years. It was phenomenal.”

Minnesota and California had quick success, and eventually the rest of the country saw the value of compulsory computer education. By 1989 almost every school district in America had a computer. “For the most part the movement was driven by local and state forces,” LaFrenz says, not the federal U.S. Department of Education.

From 1975 to 1995, MECC sold millions of copies of more than 300 different products, but it was always The Oregon Trail series that brought the most attention and profit. It went through four sequels, plus mobile adaptations and parodies, and outlived MECC's end. “MECC was sold to a conglomerate company [SoftKey] in 1995, which also bought other educational technology companies,” says Rawitsch. “However, the new owners were more interested in the consumer market than education, and in 1999, they terminated MECC as a separate entity.”

Forty-five years after Rawitsch, Heinemann, and Dillenberger sat down and created the original game in two weeks, The Oregon Trail is still a cultural landmark for any school kid who came of age in the 1980s or after. Even now, there remains a constant pressure to revive the series, so that nostalgic Gen Xers and Millennials can amble westward with a dysentery-riddled party once again.

It’s not totally out of the question, Rawitsch explains.

“The authority to initiate such a project rests in the hands of the current Oregon Trail intellectual property owners, educational publisher Houghton Mifflin Harcourt,” he says. “The Oregon Trail game could be revived and rejuvenated, if only to upgrade the code in the Oregon Trail II version to work on current computing devices.”