Smile, Frown, Grimace and Grin — Your Facial Expression Is the Next Frontier in Big Data

Engineer Rana el Kaliouby is set to change the way we interact with our devices—and each other

:focal(1896x638:1897x639)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/6f/646fef71-482b-4142-a1e1-39abebe07053/dec2015_h08_technologyranaelkaliouby.jpg)

The human face is powered, depending on how you count them, by between 23 and 43 muscles, many of which attach to the skin, serving no obvious function for survival. An alien examining a human specimen in isolation wouldn’t know what to make of them. Tugging on the forehead, eyebrows, lips and cheeks, the muscles broadcast a wealth of information about our emotional state, level of interest and alertness. It is a remarkably efficient means of communication—almost instantaneous, usually accurate, transcending most language and cultural barriers. But sometimes the data is lost, ignored or misinterpreted. If a logger smiles in the forest with no one around to see him, was he actually happy?

Rana el Kaliouby hates to see that information go to waste. Meeting el Kaliouby in her small office in Waltham, Massachusetts, I see her contract her zygomaticus major muscle, raising the corners of her mouth, and her orbicularis oculi, crinkling the outer corners of her eyes. She is smiling, and I deduce that she is welcoming me, before she even gets out the word “hello.” But many social exchanges today take place without real-time face-to-face interaction. That’s where el Kaliouby, and her company, come in.

El Kaliouby, who is 37, smiles often. She has a round, pleasant, expressive face and a solicitous manner, belying her position as the co-founder of a fast-growing tech start-up—an anti-Bezos, an un-Zuckerberg. Her company, Affectiva, which she founded in 2009 with a then-colleague at the MIT Media Lab, Rosalind Picard, occupies a position on the cutting edge of technology to use computers to detect and interpret human facial expressions. This field, known as “affective computing,” seeks to close the communication gap between human beings and machines by adding a new mode of interaction, including the nonverbal language of smiles, smirks and raised eyebrows. “The premise of what we do is that emotions are important,” says el Kaliouby. “Emotions don’t disrupt our rational thinking but guide and inform it. But they are missing from our digital experience. Your smartphone knows who you are and where you are, but it doesn’t know how you feel. We aim to fix that.”

Why does your smartphone need to know how you feel? El Kaliouby has a host of answers, all predicated on the seemingly boundless integration of computers into the routines of our daily lives. She envisions “technology to control lighting, temperature and music in our homes in response to our moods,” or apps that can adapt the content of a movie based on your subconscious reactions to it while you watch. She imagines programs that can monitor your expression as you drive and warn of inattention, drowsiness or anger. She smiles at the mention of her favorite idea—“a refrigerator that can sense when you are stressed out and locks up the ice cream.”

In particular, she thinks Affectiva, and the technology it is helping to usher into the mainstream, will be a boon to health care. A researcher testing a new drug, or a therapist treating a patient, gets feedback only at intervals, subject to all the problems of self-reporting—the unconscious desire to please the doctor, for instance, or selective recall that favors the most recent memories. El Kaliouby envisions a program running in the background of the subject’s laptop or phone that could compile a moment-by-moment record of his or her mood over the course of a period of time (a day, a month) and correlate it to the time or anything else your device can measure or track. “It wouldn’t even have to be part of a treatment program,” she muses. “You could just have it on your phone and it tells you, every time ‘X’ calls you have a negative expression, and that tells you something you may not have known.”

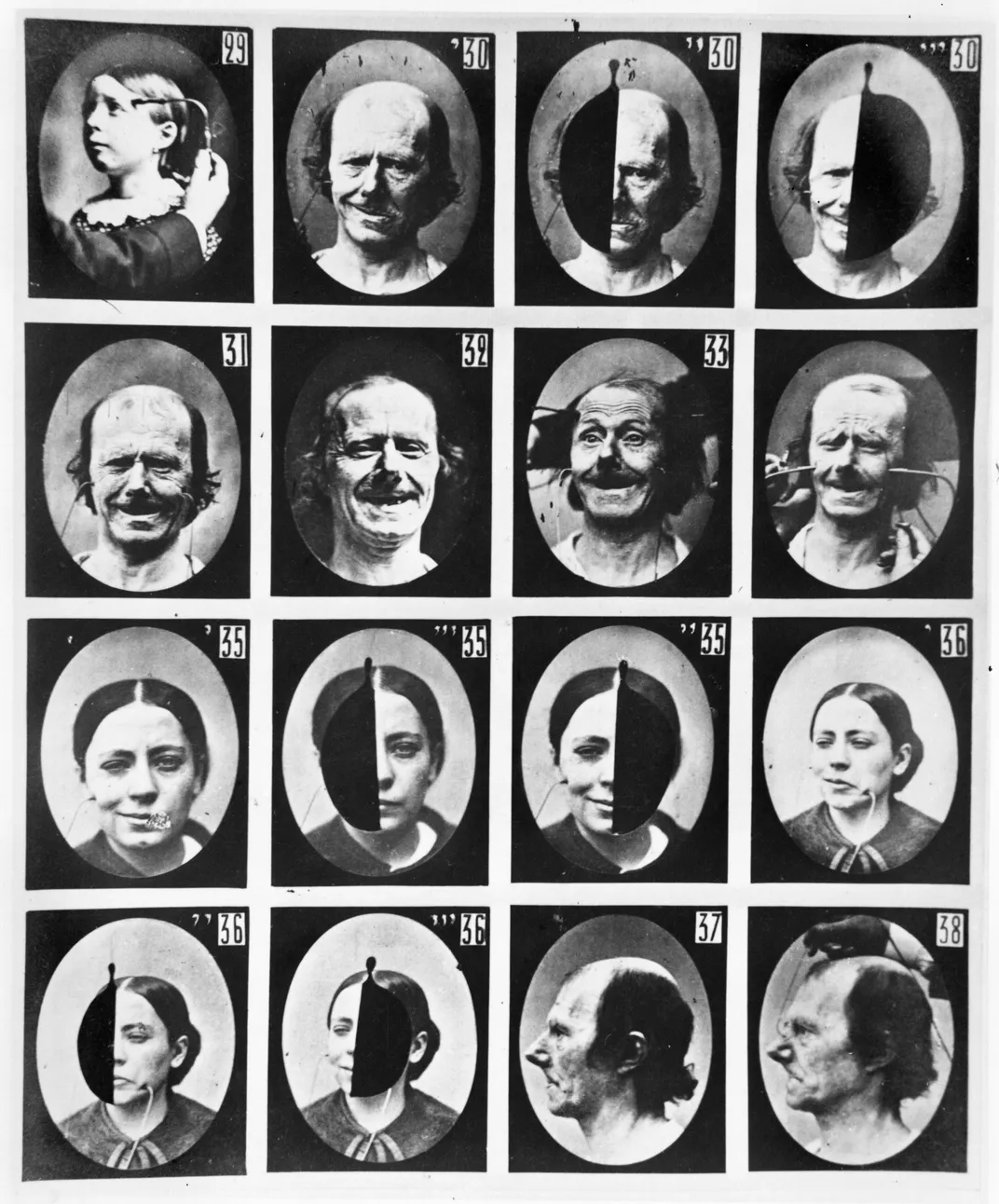

El Kaliouby promotes affective computing as the logical next step in the progression from keyboard to mouse to touchscreen to voice recognition. In the spring, Affectiva released its first commercial software development kit, which developers, interested in users’ real-time emotional states, can incorporate into their own programs—music players or gaming or dating apps, for example. And just this fall Affectiva launched Emotion As a Service, a cloud-based program to which customers can upload videos for analysis. Who might use this? A candidate about to be interviewed for a job, who is worried about appearing anxious or bored or even smiling too much. Or an airline hiring flight attendants, with hundreds of video applications to sift through in search of those who can manage a convincing smile as they bid passengers goodbye. (A genuine smile, which involves a contraction of the muscles at the corners of the eyes, is called a “Duchenne” smile, named for the 19th-century anatomist; its opposite, a forced smile that uses just the mouth, is actually sometimes called a “Pan Am” smile.)

And, of course, the devices running this software are all connected to the Internet, so that the information they gather is instantaneously aggregated, sifted and networked in the way social media apps identify popular topics or personalities. Compiled, perhaps, into something like an Affectiva Mood Index, a numerical read on the gross national happiness, or broken down into regions where smiles or frowns are currently trending.

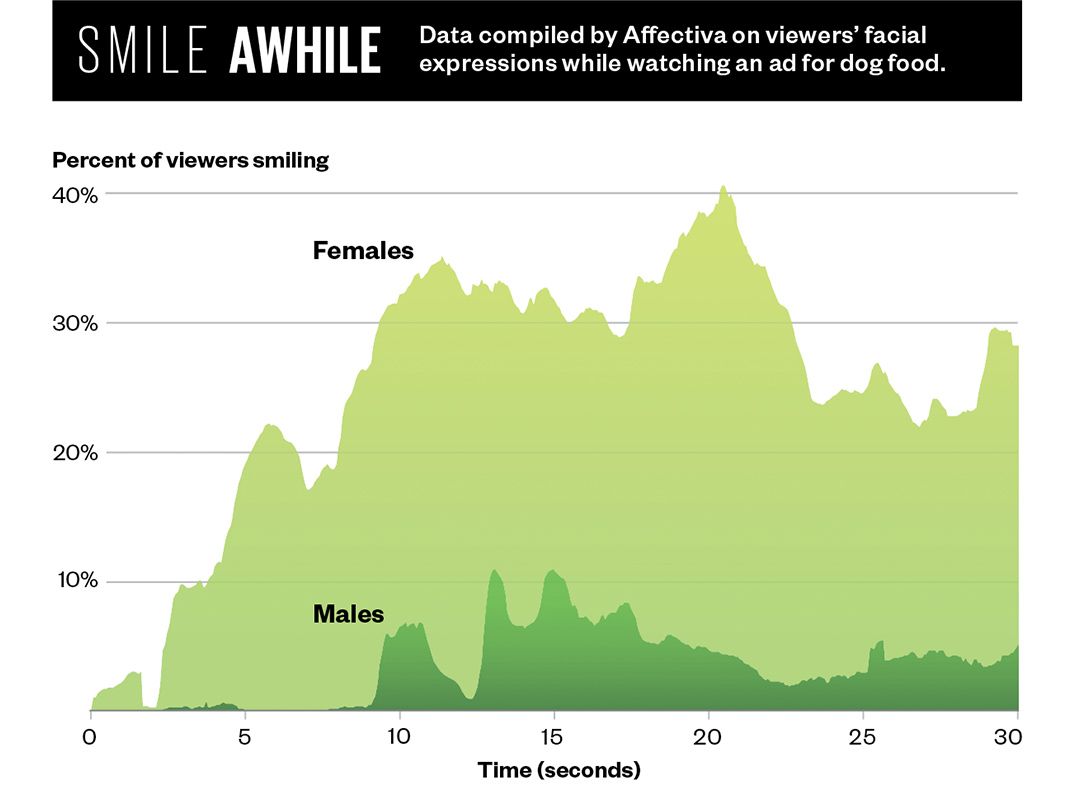

Until now, Affectiva’s main customers have been advertising, marketing and media companies. Its software automates the process of running a focus group, the cumbersome ritual of assembling a dozen people in a room to give their opinions about a new product, TV series or ad campaign; it records reactions directly, without a participant’s having to twiddle a dial or answer a questionnaire in response to a presentation. Moreover, the software expands the potential focus group to the whole world, or at least the substantial fraction of it that has a webcam-enabled computer or mobile device.

Feedback from Affectiva’s relentless, all-seeing eye helped shape a network TV sitcom, consigning two characters to oblivion for the sin of not making viewers smile. (El Kaliouby won’t identify the show or the characters.) Its software was used to build a “smile sampler,” a machine that dispensed candy bars to shoppers who smiled into its camera. With more research, it could probably be useful for crowd surveillance in airports, or to identify potential shoplifters, or as a lie detector.

But el Kaliouby has resisted these surreptitious applications, however lucrative they might be. She thinks affective computing will change the world, including, but by no means limited to, selling candy bars. “The ethos of our company,” she says, “is to use this technology to improve people’s lives and help them communicate better, not just to help advertisers sell more products.”

**********

Unlike many tech entrepreneurs, getting rich wasn’t on el Kaliouby’s original agenda. Born in Cairo to Egyptian parents who both work in technology, she studied computer science at the American University in Cairo, where she graduated in 1998, around the time computers were becoming powerful enough for researchers to think about endowing them with what in human terms is called emotional intelligence.

She continued studying computer science at the University of Cambridge, arriving just after the attacks on America of September 11, 2001. Her parents thought she risked being arrested, harassed or worse because of her heritage. But although she wore a Muslim head-covering until a couple of years ago, neither in Cambridge, England, nor in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she moved in 2006, to join the MIT Media Lab, was she ever bothered about her religion or appearance. “I think it’s because I smile a lot,” she says, smiling.

While at Cambridge, she had become interested in the problem of autism, specifically the difficulty autistic children have in reading facial expressions. She proposed building an “emotional hearing aid” that could be worn to read faces and cue appropriate behaviors to the wearer. Turned down at first for a grant by the National Science Foundation on the grounds that the project was too difficult, she and her colleagues built a prototype, consisting of a pair of eyeglasses outfitted with a tiny camera, blinking lights and a headphone, not unlike an early version of Google Glass. A second grant application was successful, and, after she moved to MIT, she and her team worked for the next three years to perfect and test it at a school in Rhode Island. El Kaliouby describes it as “a research project, and a successful one”—the autistic children who used it had overwhelmingly positive experiences—but in 2008, as the grant ended, she faced a moment of reckoning. Commercial interest in affective computing was growing, and she wanted to see it expand and flourish; putting her efforts into developing the glasses would limit it to a tiny slice of its potential uses. So along with Picard, she spun off Affectiva, while holding out hope that another company would pick up the emotional hearing aid and bring it to market.

When Affectiva was formed, the handful of “team members” who made up the company each chose a value they wanted to embody, such as “learning” or “social responsibility” or “fun.” Hers, as chief strategy and science officer, was “passion.” The 20-person company is run as a quasi-democracy, with semiannual meetings at which employees vote on priorities to pursue over the next six months. Her office has a whiteboard covered with drawings by the young daughter of one of her colleagues; she has a 6-year-old son, Adam, and a 12-year-old daughter, Jana, who live with her in the Boston suburbs (their father lives in Egypt). Her manner is mild and considerate; an hour into a morning meeting she offers to order a sandwich for a visitor, even though she herself is skipping lunch. “It’s Ramadan for me,” she says, smiling, “but it’s not Ramadan for you.”

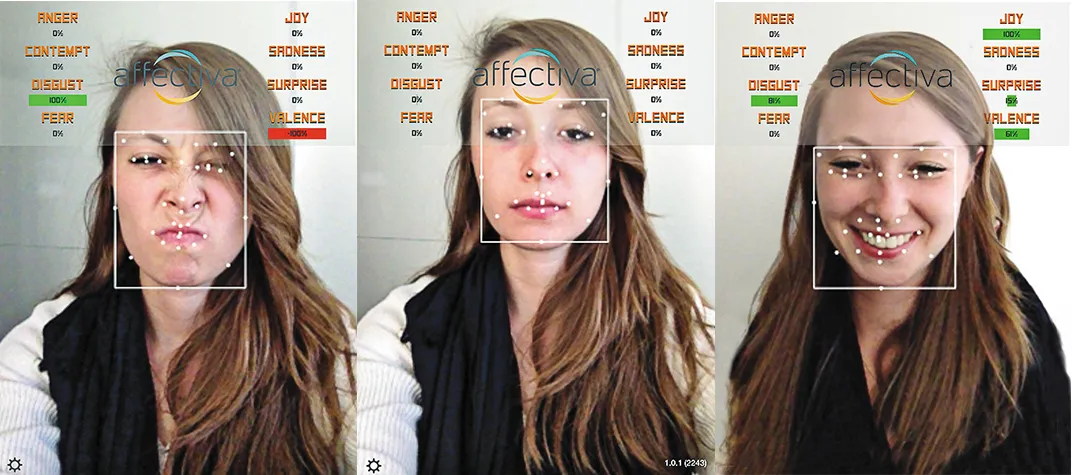

She seats visitors at a desk, facing a monitor and a webcam; the software locates the visitor’s face and draws a box around it on the screen. It identifies a set of points to track: the corners of the eyes and mouth, the tip of the nose, and so on. Twenty times each second, the software looks for “action units,” the often-fleeting play of muscles across the face. There are 46 of these, according to the standard system of classification, the Facial Action Coding System (FACS). They include inner and outer brow raisers, dimplers, blinks, winks and lip puckers, funnelers, pressors and sucks. Affectiva’s standard program samples about 15 of these at any time, and analyzes them for expressions of seven basic emotions: happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, anger, disgust and contempt, plus interest and confusion. Smile, and you can see the measure of happiness shoot up; curl your lip in a sneer and the program notes your disgust.

Or, more precisely, your expression of disgust. The whole premise of affective computing rests on what amounts to a leap of faith, that a smile conveys a feeling of happiness, or pleasure, or amusement. Of course, human beings are in the same position: We can be fooled by a false smile or feigned anger, so we can’t really expect more from a computer program, at least not yet.

Over time Affectiva has built an archive of more than three million videos of faces, uploaded by Internet users recruited from some 75 countries all over the world. Hundreds of thousands of these have been analyzed by trained observers and coded for FACS action units—a monumental undertaking, since the videos average around 45 seconds and each takes about five times as long to process. The results from the human coders, in turn, were used to “train” the company’s algorithms, which processed the rest in real time. The entire database now comprises about 40 billion “emotion data points,” a resource, el Kaliouby boasts, that sets Affectiva apart from other companies in the same field, such as California-based Emotient, probably its closest competitor.

Daniel McDuff, who joined Affectiva from MIT Media Lab and serves as director of research, is continually studying this trove for additional insights into the expression of emotions. How do they differ by age, gender and culture? (Perhaps surprisingly, McDuff has found that older people are more expressive, especially of positive emotions, than younger ones.) Can we reliably measure contempt, embarrassment, boredom, anxiety? When does a brow furrow signal confusion, and when does it indicate concentration? How can we distinguish between an expression of fear and one that signifies surprise? (Hint: Action unit 1, the “inner brow raiser,” is the marker for fear; action unit 2, the “outer brow raiser,” indicates surprise.) There is, he says, every reason to believe that the program will continue to get better at detecting expressions (although it may never completely overcome the greatest obstacle of all: Botox).

At my request, McDuff gave the program one of the great classic problems of emotion detection, the Mona Lisa, whose enigmatic quasi-smile has intrigued viewers for 500 years. With the caveat that the software works best on shifting expressions, not static images, he reported that it found no evidence of a genuine smile by La Gioconda, but rather some combination of action unit 28 (lip roll) and 24 (lips pressed together), possibly suggesting some level of discomfort.

**********

“I’m talking to you now,” el Kaliouby says, “and watching you to gauge your interest in what I’m saying. Should I slow down and explain more? Should I go to another topic? Now, imagine I’m giving a webinar to a large group that I can’t see or hear. I get no feedback, there’s no way to tell if a joke worked or fell flat, if people are engaged or bored. Wouldn’t it be great to get that feedback in real time, aggregated, from moment to moment as I go along?”

She plays an ad for Jibo, a “social robot” available for preorder on the crowd-funding website Indiegogo and developed by a former MIT colleague, Cynthia Breazeal. Looking something like a high-tech lava lamp, Jibo sits on a table and scans its surroundings, identifying individuals by face and interacting with them—relaying messages, issuing reminders, making routine phone calls, even chatting. This is another potential application for Affectiva’s software—the companies are in talks—and it’s “a very exciting prospect,” el Kaliouby says.

Exciting to some, but the prospect of emotion-processing robots is alarming to others. Sherry Turkle, who has long studied how humans relate to computers, warns in her new book, Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age, about the “robotic moment,” when machines begin to substitute for human companionship. Turkle believes that scientists like el Kaliouby and her team can do what they say they will. “These are all brilliant, gifted people doing brilliant work,” she says. And she agrees that in certain contexts—dangerous environments, such as outer space or around heavy machinery, where you want to enlist every possible mode of communication—affective computing has a role to play. “But the next step,” she says, “does not follow at all. The next step is, Let’s make a robot friend. I’ve interviewed parents who are happy their children are talking to Siri, and I think that’s not taking us down a road where we want to go. We define ourselves as human beings by who we associate with, and it makes no sense to me to form your sense of self-esteem in relation to a machine. Why would you want a computer to know if you’re sad?”

Even el Kaliouby is inclined to agree that “we’re spending more time than we should with our devices,” having in mind, naturally, her preteen daughter, whose gaze locks on her smartphone screen.

But she regards the trend toward ever-greater connectivity as irreversible, and she thinks that, while users should always have to opt in, we might as well make the best of it. She predicts that our devices will have “an emotion chip and a suite of apps that use it in a way that adds enough value to our lives that outweighs people’s concerns in sharing this data.” She draws an analogy to GPS devices: Affective computing can help us navigate emotional space the same way phone apps help us get around in physical space. “Everyone worried about location-sensing devices when they first came out, too: They were invading our privacy, they were tracking us all the time,” she says. “Only now, we’d all be lost without Google Maps on our phones. I think this will be the same.”

**********

Related Reads

Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ