Rosanne Cash on Discovering New Artistic Terrain

The singer-songwriter looked to her Southern ancestors to come up with a different kind of concept album

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/69/44/69440eb1-d7a5-4230-8cf1-ab84f6a26926/nov14_a01_rosannecash.jpg)

Innovation is not just for the young. Rosanne Cash learned this in 2011, the year she turned 56, as she pondered what her next album would be. She had just finished touring in support of her 2009 album, The List, a dozen songs selected from the list of essential country and folk numbers that her famous father had given her to learn when she was a teenager. That record had earned glowing press and robust concert-ticket sales.

“So many people told me, ‘Are you going to do The List, Part Two?’” she recalled backstage at the Shenandoah Valley Music Festival in July. “That might have been a good business decision, but it made me feel hollow inside, like I’d be faking it. How boring to stick to what you’ve already done.”

Instead, Cash found her way to a different way of songwriting, and that led to The River & the Thread, a new album of 11 originals that has received even warmer praise than The List. In an era when most listeners download music as single tracks or subscribe to an Internet-radio service that strings single tracks together, the notion of an album—a collection of songs greater than the sum of its parts, whose individual tracks inform and reinforce one another—seems increasingly obsolete. So how can album advocates get through to a public that thinks of songs as free-floating atoms that never bond? By inventing, as Cash has, a new kind of concept album. The River & the Thread, unlike such fabulist projects as Tommy, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and The Wall, is based not on fantasy but on a form of journalism.

The songs sprang from a series of trips that she and her husband, John Leventhal, who doubles as her record producer, took from their home in New York City to the Deep South. Their objective was to explore the hillbilly and blues music they love so much and the childhood geography of her Arkansas-raised father, Johnny Cash, her Texas-raised mother, Vivian Liberto, and her Virginia-raised stepmother, June Carter. Out of this exploration came a series of songs that each depicted a particular person or town but that together formed an astonishing portrait of the region as a whole.

It was a radical departure for this notoriously autobiographical writer. Most of her previous songwriting had taken place in her own house or in her own head; she was so introspective that one of the finest albums she’s ever made was titled, aptly, Interiors. Now she was challenged to evoke landscapes far from her own neighborhood and to have voices other than hers narrate the songs. To push herself further, she decided to write only the lyrics and to allow Leventhal to write all the music.

“The word ‘reinvention’ makes me a little nervous,” she told me, “because it implies a self-conscious architect, and I’ve never been that—sometimes to my own detriment. I’ve never been good at five-year plans. I’ve always moved through life on instinct. But by following my own muse I did keep trying new things. There’s no way we could have said, ‘Let’s go down south and write a record about it.’ It wouldn’t have been the same. But having gone down south and having been so inspired by it, the natural result was these very different songs.”

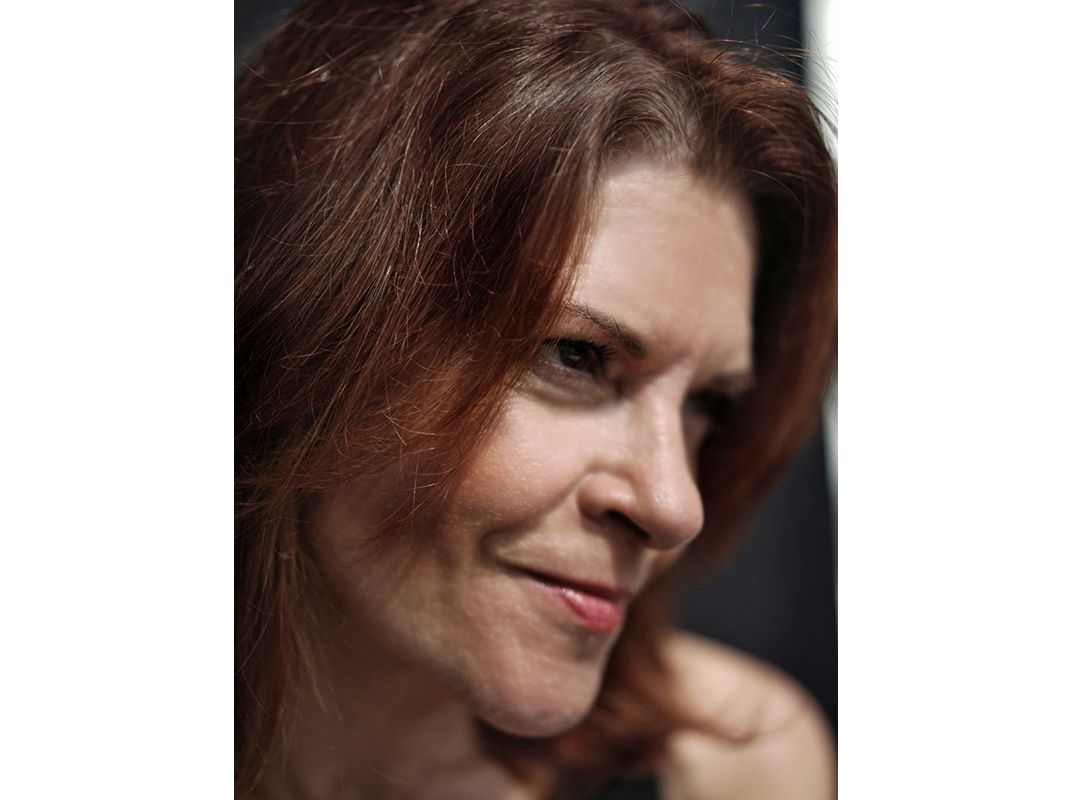

Cash, now 59, sat in the festival office, her dyed-red hair spilling to her shoulders, her oversize man’s shirt open over a black top, a sandal dangling from her right foot crossed over faded jeans. Sitting across from her was her tall, lanky husband, sporting a gray goatee and a snap-button blue shirt.

“I thought the next record shouldn’t just be the next 12 songs we wrote,” Leventhal said. “I thought it should hang together as a whole and be something different than what we’ve done before. One day we were at Johnny’s childhood home at the end of this lonely road, and it had a real ghostly feel because it hadn’t been taken care of. It reminded me of how much I love the South, even though I’m not from there, and something flashed: ‘Maybe we could write something about the South.’”

Cash gets dozens of invitations every year to participate in projects honoring her father, and she turns down almost all of them. Her job, she explains, is not to maintain the Johnny Cash legacy; it’s to write and sing her own songs. But in 2011, she got an invitation she couldn’t refuse. Arkansas State University was going to buy her father’s childhood home and was raising money to fix it up. Would she help?

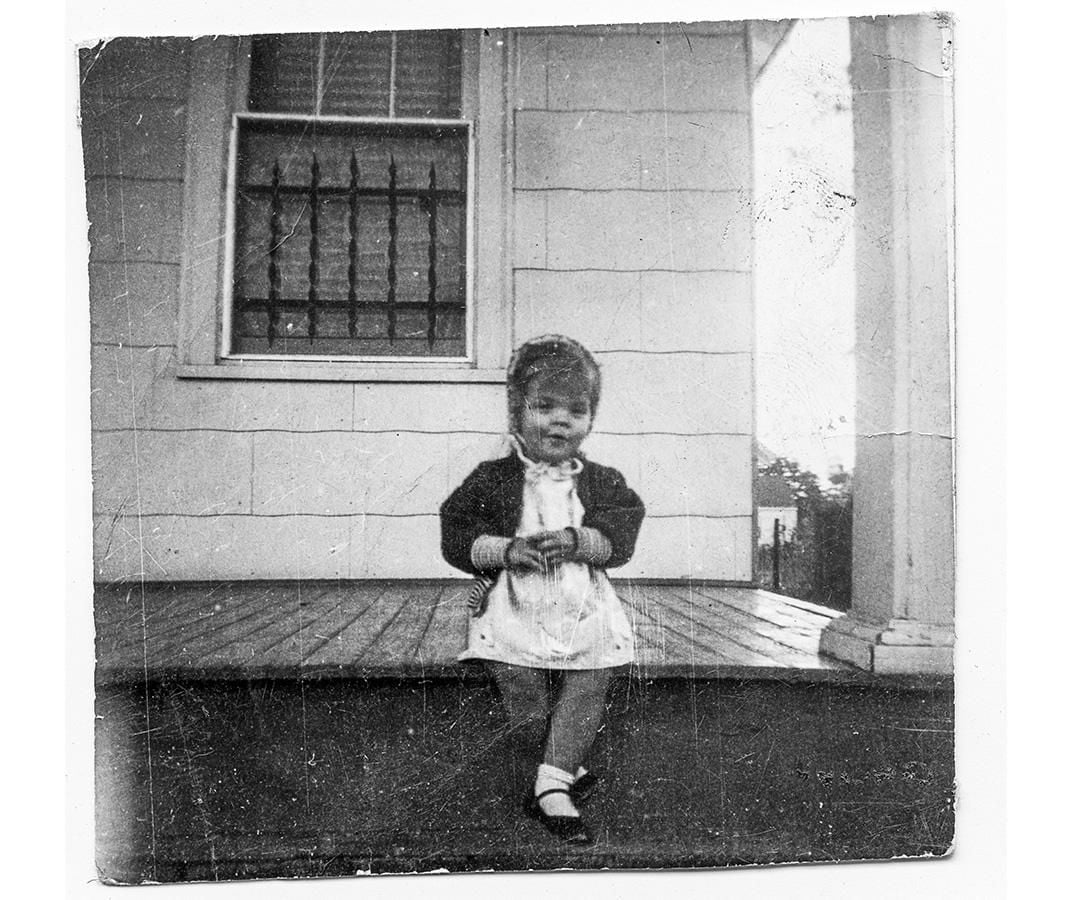

Amid the Great Depression, President Roosevelt’s New Deal began establishing “colonies” where starving farmers could get a second chance: a farmhouse, chicken coop, seed, tools and 20 acres. One such colony opened as Dyess, Arkansas, in 1934, and a 3-year-old Johnny Cash moved in with his parents and siblings. The house was new—Johnny’s earliest memory was of the five empty cans of paint that stood alone in the vacant house.

“It saved their lives,” Rosanne said. “They were so poor, at the very bottom of the ladder. But my dad was so proud of where he came from. I got involved in this project because he would have cared about it more than anything. I did it for my kids, because I wanted them to know he started out as a cotton farmer.”

But how could she turn that experience into a song? Describing her visit to the farmhouse in 2011 would have been too many generations removed. She had to get out of her own head and see the world through someone else’s eyes. She could have sung the song from her father’s point of view, but that would have been too obvious, so she chose to sing it from the perspective of her grandmother Carrie Cash.

She performed the resulting song, “The Sunken Lands,” at the Shenandoah Valley Music Festival, a concert series on the grounds of a post-Civil War-era resort in Orkney Springs, Virginia. The mist from an early-evening rain hung between the dark-green oaks and the hotel’s white porches and balconies as Cash and Leventhal took the stage of the open-sided pavilion. Performing without a band, Leventhal opened the song with a rising melodic figure on the guitar, and Cash transported herself back to 1935 to sing, “Five cans of paint / And the empty fields / And the dust reveals. / The children cry; / The work never ends. / There’s not a single friend.”

“I realized that if I just wrote about my own feelings, the song would collapse on itself,” Cash said. “At this stage of life, the questions we ask ourselves—‘Where is my home?’ ‘What do I feel connected to?’—are different from the questions we ask at 25. I needed a new way of writing to answer those questions. I’m still writing about love, and need is still in there, but those feelings become stronger when they’re taken out of your own head. Somehow the feelings become more specific when they’re imbued with the character of a place. A love story in Memphis is different from a love story in Detroit.”

During the Orkney Springs show, Cash sang her unreleased arrangement of Bobbie Gentry’s 1967 single, “Ode to Billie Joe,” one of the strangest number-one hits ever. A Mississippi family sits around the dinner table, sharing the biscuits and black-eyed peas with the local gossip, including the news that Billie Joe McAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge. Only in the fourth verse do we learn that the narrator and Billie Joe had been seen throwing something off the same bridge. Gentry never discloses what that something was.

Cash, now wearing a long black jacket over a black top, introduced the song by recounting her trip with Leventhal to the same bridge. “We thought it would be this grand structure, but it was this modest bridge over this modest river,” she said. “We were there for half an hour and one car went by. We asked each other, ‘What are we going to throw off the bridge?’ So we threw off a guitar pick. John took an iPhone picture of me on the bridge, and that’s the album cover. The record label didn’t want to use an iPhone photo on the cover, but we won.”

“We’ve been doing that song a lot live because we’re fascinated with it,” Leventhal said after the show. “You can hear the dirt beneath the strings, and it tells a complete story in five verses without explaining everything. The lyrics whetted our appetite for writing more story songs, and the sound of that record made me want to bring out the blues and soul that’s always been buried in Rosanne, that sultriness in her voice. We decided we wanted to make an album of 11 songs as good as ‘Ode to Billie Joe.’”

“I’d always wanted to write story songs,” Cash replied. “I wanted to write those Appalachian ballads with four characters and 12 verses, but I’d always felt it wasn’t my forte, that it was beyond me. When I wrote ‘The House on the Lake’ about my father’s home in Tennessee, the description of the rose garden and the people dying felt so specific I felt like I couldn’t sing it live; it was too personal. But when I did, this guy came up to me and said, ‘We all have that house on the lake.’ That’s the discovery I made on this record: The more specific you are about places and characters, the more universal the song becomes.”

Later in the show Cash introduced the song “Money Road” by explaining, “You can walk from the Tallahatchie Bridge to Bryant’s Grocery, where Emmett Till got in the trouble that got him lynched, to Robert Johnson’s grave. They’re all along Money Road in Mississippi.” She sings the song as if she were the teenage narrator of “Ode to Billie Joe” 40 years older, living in New York, convinced she had left Mississippi behind, but discovering, as she sings, “You can cross the bridge and carve your name / But the river stays the same. / We left but never went away.”

She elaborates on this theme in “The Long Way Home,” a song about coming to terms with a South she thought she had escaped—if not when she moved from Memphis to California at age 3, then when she moved from Nashville to New York at age 35. “You thought you’d left it all behind,” she sings. “You thought you’d up and gone. / But all you did was figure out / How to take the long way home.”

In a remarkable coincidence, Cash’s former husband and producer, Rodney Crowell, has a similar song with a similar title, “The Long Journey Home,” on his new album, Tarpaper Sky. “We’ve both reached an age,” Crowell says, “where in the rearview mirror this journey called life has more stacked-up mileage than out the front windshield. Which is the reason we are both wringing twice as much out of life—and therefore art—as when we were in our 20s and 30s.”

Still friends, Crowell, Cash and Leventhal co-wrote “When the Master Calls the Roll,” the most ambitious story song on The River & the Thread. It had begun as a possible song for Emmylou Harris but was completely revamped by Cash’s renewed interest in the South and the ultimate Southern story: the Civil War. It’s the tale of a Virginia woman who advertises for a husband in a newspaper and finds the perfect match, only to watch him march off to battle, never to return. It’s Cash’s most skillful use of narrative arc and character development in song. (She annotated the lyrics for the print version of Smithsonian.)

She told the Orkney Springs crowd that she was thrilled to finally sing the song in Virginia—the home not only of the song’s characters but also of June Carter; June’s mother, Maybelle; and Maybelle’s cousin Sara; and Sara’s husband, A.P. The last three, performing as the Carter Family farther south down the same Appalachian Mountain chain that now cradled Cash and Leventhal, created the foundation of modern country music.

At last Cash had a song with a story so tightly structured and so closely wedded to its Celtic melody that one could easily imagine the Carter Family singing it. She couldn’t have written it five years ago, but she learned that her profession, like anyone’s, requires constant innovation if it is to remain fresh. “I feel alive when I’m immersed in my work—when I’m fully employed, as Leonard Cohen says, as a songwriter,” she said. “You have to keep cracking yourself open or you become a parody of yourself.”

Related Reads

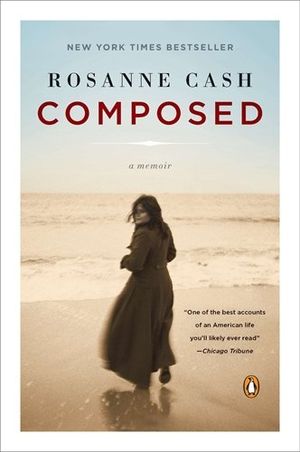

Composed: A Memoir

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/geoff-vancouver-bio-lightened.jpg)