Stanford Researchers Map the Feelings Associated With Different Parts of London

The university’s Literary Lab combed British novels from the 18th and 19th centuries to determine if areas elicited happiness or fear

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/ca/bfca329c-3d33-431c-8d13-2cf6cfb618a3/18th-century-map-of-london.jpg)

How do cities make us feel? Does the Champs-Élysées elicit happy emotions? Does the East River generate fear?

A new project from Stanford’s Literary Lab attempts to show how British novels of the 18th and 19th century portrayed different parts of London, giving a peek into how readers might have viewed those parts of the city. The end product, a digital pamphlet full of maps, is called “The Emotions of London.”

“[W]e hoped to better understand aspects of the relationship between fiction and social change in the 18th and 19th centuries,” says Ryan Heuser, a doctoral candidate in English who co-authored the pamphlet. “How did novels represent the vast changes in London's social geography? And how did they help to shape this geography, especially through their ability to imbue locations within London with specific emotional valences?”

In other words, did novels accurately track the ways the city was changing? And if a novel portrayed a part of London as happy or scary, did that help make those places happier or scarier in reality?

To create the pamphlet, researchers used a computer program to search for place names mentioned in 18th and 19th century novels set in London, and plotted them on a map of the city. They then paid workers on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to read the passages surrounding the mentions—some 15,000 of them. The readers were asked to identify happiness or fear, and their responses were compared to readings by English graduate students, and to a computer program designed to identify feelings.

In general, the researchers found that London’s West End—a historically wealthy area—was associated with emotions of happiness, while the East End—a historically poor area—was associated with fear. Since most readers at the time were middle or upper class, this gives us a look into how they might have viewed the city, including the poorer areas they’d probably never visited.

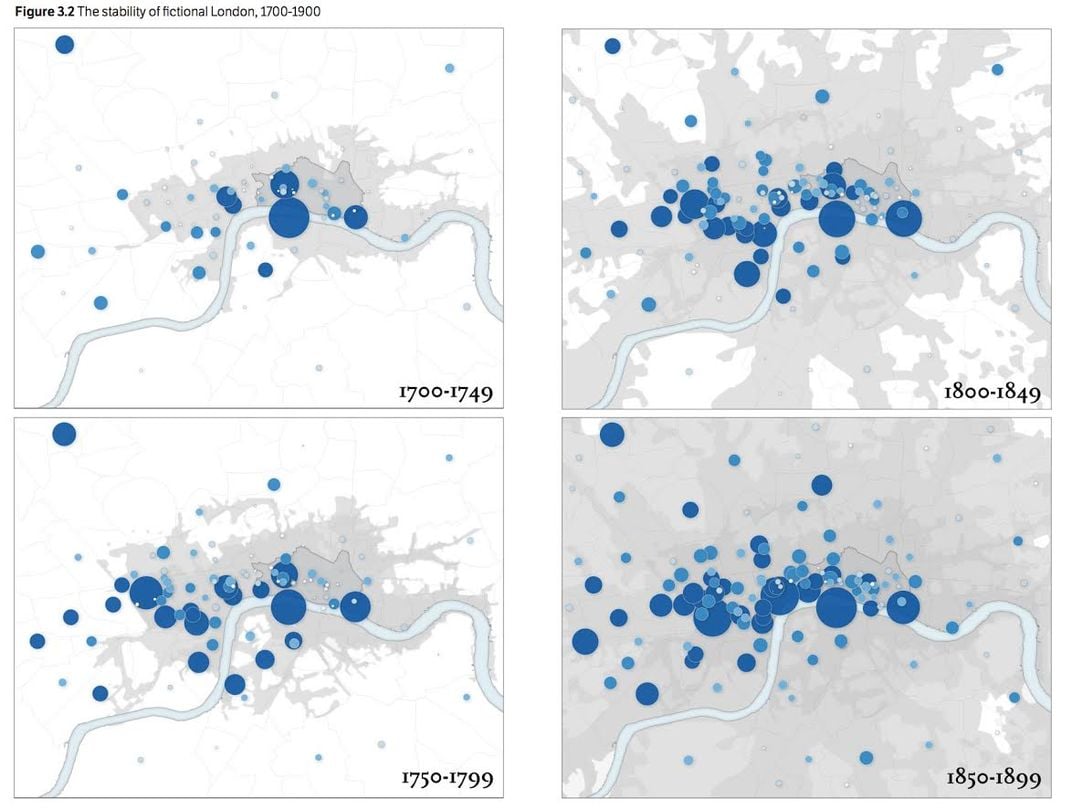

It was surprising, Heuser says, how “the literary geography of London remained remarkably stable, even as the distribution of people across London radically transformed.” In other words, the way places were described in books stayed the same, even as those places changed. For example, the City of London, the ancient heart of the city, had a steady population decline throughout the 19th century as it became a commercial center (today it is home to London’s financial center; saying “the City” is roughly equivalent to saying “Wall Street”). Yet it was still mentioned in novels just as much as before. Though the rest of London was growing wildly, it was hardly ever mentioned, as novelists stuck to writing about the well-trodden territory of the West End and the City. In a sense, the London of the novel was “stuck” in time as the real London moved forward.

The pamphlet also looks at where specific authors tended to set their novels. Catherine Gore, one of the Victorian "silver fork" writers, so-called for their depictions of the upper classes, mentioned West End locations more frequently than any other writer. Walter Besant, whose novels sensitively depicted the poor, wrote about the East End more often than others. Charles Dickens, perhaps the most famous of all London novelists, set his works all over the city, a unique quality among his peers.

The project was attempting to build on other works in the field known as literary geography, says Heuser. One of the major inspirations was Atlas of the European Novel, a 1998 work by the Stanford literary critic Franco Moretti, who co-authored the pamphlet. That book featured 100 handmade maps showing connections between literature and space—where in England various elements of Austen’s novels took place, or where the murders in Sherlock Holmes stories occurred.

The team decided to focus on London for two main reasons, Heuser says. First, London was the center for publication of English language novels. Second, a large proportion of the British population lived there; it was rapidly becoming the largest city in the world.

“Focusing on London, then, allowed us to ask how novels might have registered these profound social changes in their fictional representations of the city,” he says.

Stanford’s Literary Lab is a research collective that uses digital tools to study literature. One recent project analyzes how the language of World Bank reports became more abstract and removed from everyday speech over the decades. Another project created visualizations of which novels various groups (the Modern Library Board, Publishers Weekly and so on) considered “the best of the 20th century”—did they overlap? Was there any rhyme or reason to the lists?

The Emotions of London project was a collaboration between the Literary Lab and the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis (CESTA). CESTA is about using digital tools for humanities research. Their projects are about visualizing information about history and culture in new, often interactive ways. One project, Kindred Britain, is a database of 30,000 famous Britons that can be searched to show connections between different people—how was Charles Darwin connected to Virginia Woolf? How many people does it take to get from Henry VIII to Winston Churchill? Another, The Grand Tour Project, is creating a dynamic, searchable database of images and media having to do with 18th century European tourism in Italy, giving viewers a look into what the so-called “Grand Tour” was like.

Heuser says he hopes that other people might be inspired by his team’s work to think about how novels help create our sense of the cities we live in.

“Does fiction help to maintain a version of a city's geography that is ‘stuck’ in the past?” he asks. “Or does it help to advance our understanding of evolving urban boundaries and geographies?”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)