These Glasses Could Help the Blind See

Developed by Oxford scientists, SmartSpecs capture real time images and enhance the contrast for legally blind users

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9c/96/9c96954f-9c0e-4bc3-b6ed-d22f2e76534b/smartspecs1.jpg)

Many people with normal vision imagine blindness as utter darkness, the unbroken black of a dead TV screen. But approximately 90 percent of people who are designated as legally blind (defined as having less than 20/200 vision in your better eye, with corrective lenses) have some degree of remaining sight. They may have decent peripheral vision but no sight in the center, or they may have only central sight, or “tunnel vision.” They may be able to see light or large objects that are very close.

Now, scientists in the United Kingdom are trying to address the needs of the legally blind with a pair of “smart” glasses.

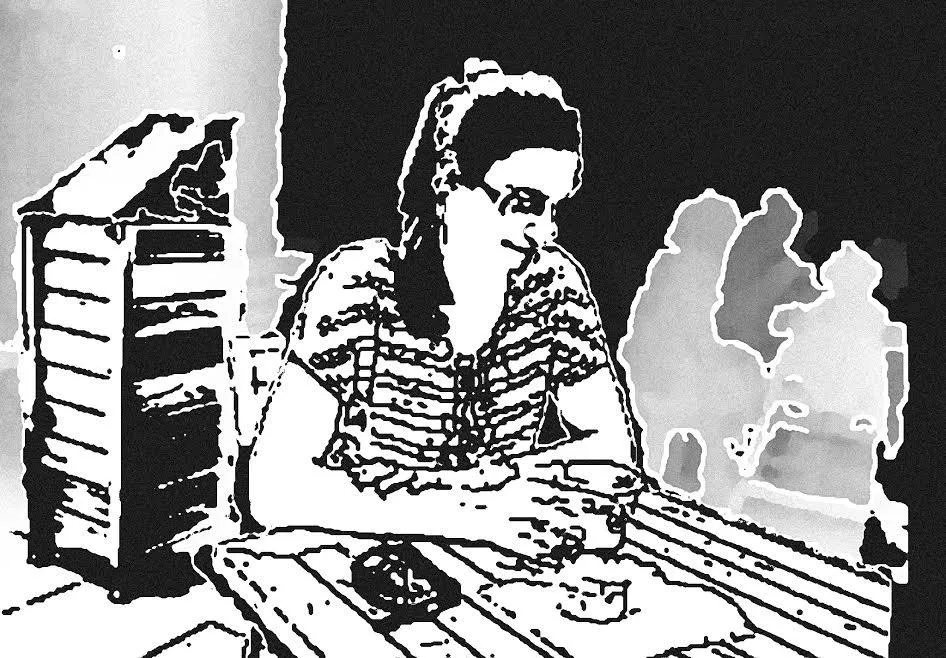

SmartSpecs, developed by a research team at a University of Oxford lab, use 3D cameras originally developed for the Xbox to capture real time images. The images are then put into high contrast and displayed on a screen in front of the user’s eyes. Dark things become black, while bright things become white. Far away objects are simply erased to reduce visual clutter.

Many visually impaired users find the high contrast allows them to see things they normally couldn’t. Furniture that might ordinarily blend in with a same-colored floor, turning it into a tripping hazard, becomes bright white. Doorways are enhanced. Even faces, which might normally appear as a blur, turn into crisp black and white cartoons. Smiles that might go unseen can be appreciated.

“All you need to do is get a few bits and pieces of an image and your brain fills it in,” says Stephen Hicks, the Oxford neuroscientist leading the project. “[SmartSpecs are] sort of tapping into that intuitive sense of vision—you just need a bit of shadow here and there, like walking around your house by moonlight.”

The team has been testing prototypes for about four years, using about 100 testers. They’re hoping to become the first to make a portable, high-tech, vision-enhancing device that can be used without a bulky computer apparatus.

Only about a third of the users find the glasses useful to some degree, Hicks says. Unfortunately blindness takes on numerous forms, some of which are not amenable to the kind of enhancement offered by SmartSpecs.

But for those who can benefit from the glasses, the experience can be life-changing. He recalls being with a tester in New York, who put on the glasses and was suddenly able to see an old friend.

“She was quite emotional about it, because she hadn’t really seen a face with that amount of definition in a long time,” he says.

Hannah Thompson, a legally blind British academic, was one of the early testers of SmartSpecs. On her blog, she describes how SmartSpecs allowed her to do something most of us take for granted: shop for food in a busy market.

“The first thing that struck me as I looked at the cheeses on display was that I could, for the first time ever, distinguish their different shapes and sizes,” she writes.

Thompson said the glasses could benefit her in a number of specific situations—walking around in dappled sunlight, which can be difficult for the visually impaired as it breaks up the sharp edges of objects making them harder to see, and navigating low-light situations. She hopes, though, that future models have cameras accuate enough to read small text, such as the names on the cheese labels.

The Oxford team is working in conjunction with Britain’s Royal National Institute of Blind People. The project is putting £500,000 (about $776,000) to use that the team won in the 2014 Google Impact Challenge, a contest for innovative solutions to the issues faced by people with disabilities.

There are a number of high-tech glasses for the visually disabled on the market or under development. On the complex, medicalized end is the Argus II, which involves a pair of camera-equipped glasses that transmit images to a retinal implant surgically placed in one of the user’s eyes. On the simpler side are magnifying visors worn like glasses for reading or other close work. Other devices, like the Canadian-created eSight, work similarly to SmartSpecs, but have a bulky, somewhat science-fiction look, and come with a processing unit that must be carried in a bag or backpack.

“They look a bit like a virtual reality headset,” says Hicks. “Our real focus is on a pair of glasses that approach something people wouldn’t feel too self-conscious to wear.”

Part of making glasses look less off-putting is designing them so the user’s eyes are visible. Since eye contact is such a big part of human interaction, devices that obscure the eyes tend to project a bit of a “cyborg” appearance. SmartSpecs have tinted, sunglasses-like lenses that leave the user’s eyes visible, while the cameras are mounted above. While SmartSpecs’ current prototype is still bulky and would likely attract curious stares in public, Hicks says future versions will be much slimmer.

Hicks’ group is now launching a nine-month test of the latest prototype. Testers will take home the glasses for four-week “in the wild” trials, then report their experiences to the team.

The next step will be equipping the glasses with semantic imaging software, which can automatically recognize different types of objects. This would allow users to say “glasses, find me a chair,” and the glasses would identify chair-like objects in the vicinity.

An improved version of SmartSpecs, utilizing testers’ input and possessing a higher powered battery and smaller frame, should be available on the market next year, Hicks says. He expects the glasses to retail for around £700 (around $1100).

“We’re trying to make something that actually is a desirable thing for people to be able to wear,” Hicks says. “You can make the best thing in the world, but if it makes no sense to wear, it’s not very useful.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)