These Photographs From Space Show What Humans Have Done to the Earth

In new book, vivid satellite images of the planet evoke what astronauts call “the overview effect”

More than 550 people have shucked the bonds of Earth and visited space. They unanimously describe the experience as profound. But it isn’t the empty blackness between stars or the power of the harnessed explosion they ride that so affects these space travelers. It’s the feeling they get when they look back at Earth.

“When we look down at the Earth from space, we see this amazing, indescribably beautiful planet,” says astronaut Ron Garan. “It looks like a living, breathing organism. But it also, at the same time, looks extremely fragile.”

Neil Armstrong did call his first step on the moon’s surface a giant leap, but when he looked at Earth he says, “I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small.”

This moving experience is called “the overview effect.” Space travelers have struggled to explain exactly what it is about seeing the planet as a pale blue dot that evokes this feeling. Yet artists, filmmakers and other Earth-bound creatives have been inspired by what the astronauts can share. Author Benjamin Grant, who just released a book, Overview: A New Perspective of Earth, that draws on the rich photographic resources collected by satellites, is the latest person striving to convey the feeling.

“When I learned about the overview effect, it completely changed the way I thought about the world,” Grant says.

Grant got his own taste of the overview effect after he typed the query “Earth” into Google Earth. Instead of zooming out and showing him the globe, he says the program zoomed in to Earth, Texas. Green circles, irrigated fields that pop out from the brown landscape, surround the small community in the western part of the state. “I was amazed and astounded and had no idea what I was seeing,” says Grant. “From there I became completely obsessed with finding patterns in the Earth.”

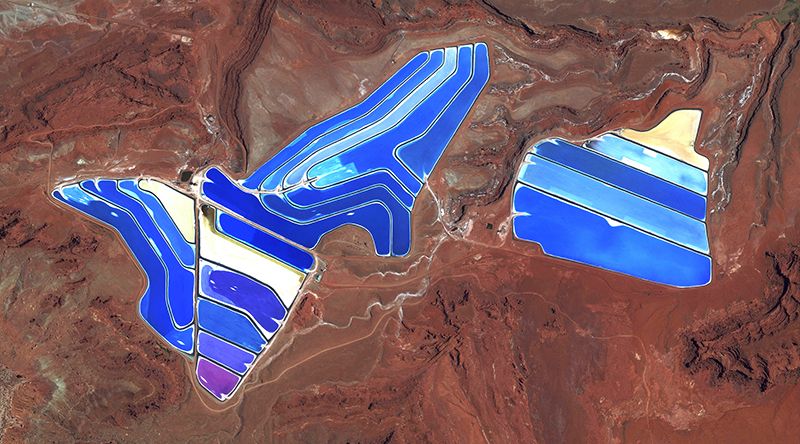

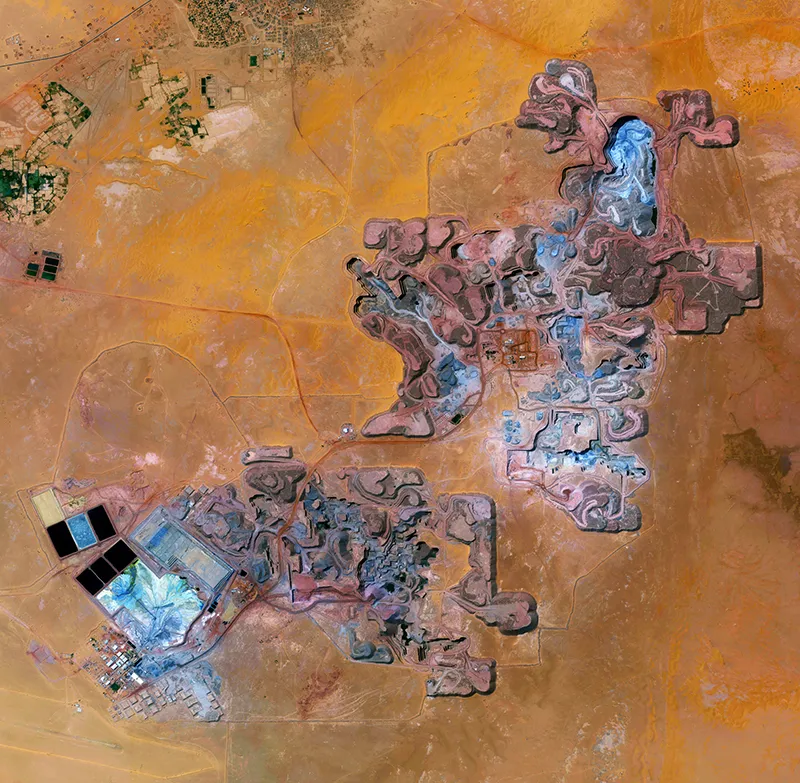

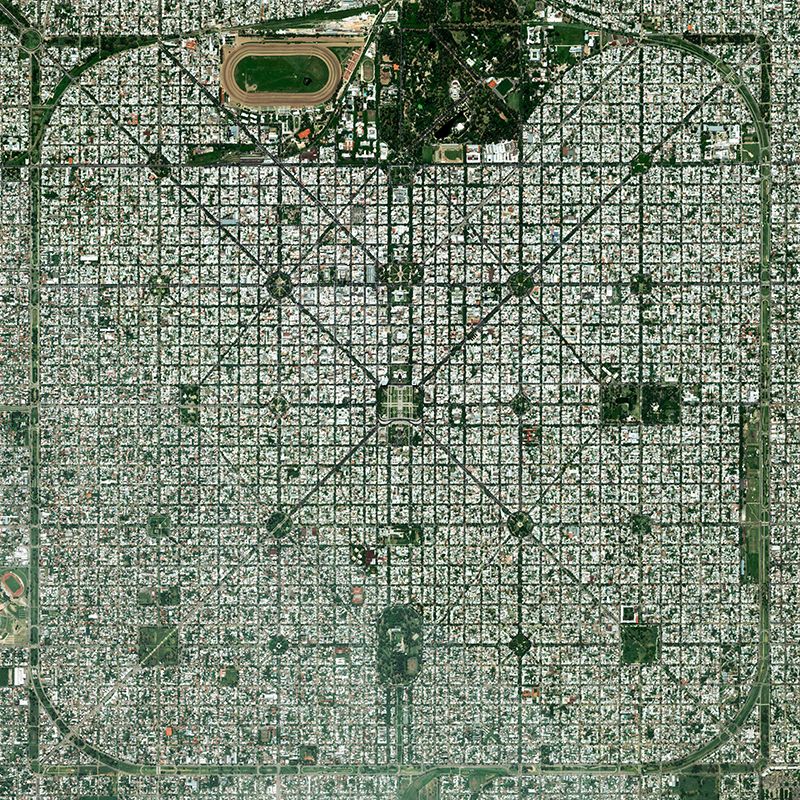

Grant’s curiosity led him to search for other striking ways that humans have altered the landscape of the planet. From the orderly grid of city streets to the patchwork quilts of agricultural areas, from the vivid hues of mining waste ponds to the sinuous curves of highway interchanges, Grant kept finding intriguing marks of civilization etched on the surface of Earth. In December 2013, he started to collect the images and explain what they were in a blog he calls “Daily Overview.”

The new book is a collection of more than 200 photographs Grant found over three years. As curator, he edited and stitched together raw images taken by satellite company DigitalGlobe. He then organized his creations into eight chapters that explore how humans are shaping the Earth. “Where We Harvest,” for example, looks at how we cultivate the land and sea to feed ourselves. In “Where We Play,” Grant shows us parks, beaches and resorts.

These images from above all have the same curious flatness one can see from a plane window. Removal from the immediate and overwhelming complexity of life on the ground encourages a sort of clarity of perspective. Life below can seem small and even quaint. But there’s also a contradiction that becomes clear from this vantage point. Some of these structures and built landscapes are enormous. Knowledge of that fact belies the neat, orderly illusion that distance gives.

The book’s photographs are saturated with color. The large pages give plenty of space for the images to take center stage, while short but informative captions lurk unobtrusively to the side. Even with the ubiquity of satellite-based images available online, this is a unique view of the globe we all call home.

Grant spoke to Smithsonian.com about the book and its message.

Can you convey the overview effect in a book, or does one need to travel to space?

I think what the images do is provide a little of that effect for all of us stuck here on the ground. They provide a new vantage point and new way to think about our species and what we are doing to the planet.

I'm trying to get people to feel awe when they look at the images. When you are looking at something that is so vast and so grand and bigger than anything you've seen before,

your brain is forced to develop new frameworks. You have to reset, in a way, to comprehend what you are seeing. You have to look for pieces of the photograph that give you a sense of scale. You have to kind of mentally go up into the camera in the satellite and back down to Earth to understand what you see.

I don't know if the project fully gets across what astronauts saw, but I was fortunate to get to speak to astronauts as I was working on it. They said that it did remind them of looking back down at Earth.

At this point, we have a lot of satellite images available to us. How is your collection unique?

I take this satellite imagery that we have access to from Google Earth and other programs and started treating it more like art, or like photographs. I take the time to compose them and enhance certain colors to get across what I want to convey in that image.

For me, the artistic composition is a way to pull people in and to make them curious. If I have done a good job of pulling people in, I get them to say more than, "That is pretty," but "Wow, what is that?"

Why do you focus on human-influenced landscapes?

I made the decision on the first day to focus on human landscapes we have created. I'm not necessarily saying these landscapes are good or bad or that we are destroying the planet. But I am creating an accurate picture of where we are now.

Before people make decisions on what to do about the planet, they need to understand what we have done. Hopefully then, we can understand how to create a better and smarter planet.

But, I think when I made that decision, I didn't know all the different ways that it would manifest.

Are there particular images that were surprising to you?

The chapter on mining, "Where we extract," is pretty remarkable to me. It started with the research to figure out what these mines were and how the materials we are extracting from the Earth are used in our home and what we eat…in everything. To see where these materials are coming from makes you more informed. You realize how much needs to happen in different places around the world to get the aluminum in your car or the coal that we burn.

At the same time, the images are profoundly beautiful. That creates an interesting tension: You know this can't be good for the planet, that chemicals are being released into the environment, and at the same time you really enjoy looking at it. Mining often creates these textures, patterns and colors that can't exist anywhere else.

There are other images too where it is pleasing to look at, but you know it can't be good. I have a beautiful image of the Dadaab Refugee Camp in Kenya. There's the stunning red of the soil and then an intriguing pattern on top of it. But then you realize that this is an expansion for a refugee camp that already has 400,000 Somali refugees, and they are planning for more.

In a weird way, this is one of the best things about the project. It shows people things they may not want to look at or read about and encourages them to do exactly that.

Why did you decide to do a chapter on "Where we are not?”

I couldn't help but be interested in creating this juxtaposition. Not only is the book showing the planet and what we are doing to it, but I also wanted to encourage people to develop an appreciation for the natural beauty of the Earth itself.

Astronauts talk about the patterns in clouds and water, where you don't see man-made lines or constructions. They develop this incredible appreciation for this oasis that is floating in darkness. The final chapter touches on that, this pure natural beauty that has nothing to do with us.

There is also this sense of time. Mountains that rose up because of tectonic activity or rivers that meander—these are things that could only have been created over lengths of time that are almost unfathomable. The previous chapters focus mostly on things that have been created very recently, in the past century. So the book is about not only what we are doing to the planet, but how quickly we are doing it.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

Before people start acting in service of the planet, I think they need to have a better idea of what is going on. These images are a fascinating, relatively new way to look at our planet. Hopefully, the book encourages people to start asking questions. I think that inquisitiveness will lead to better behavior.

This planet will be here long after we are gone. We should develop an appreciation and love for it, because it's the only planet we have, for now.