This Clear Plastic Material Harvests Solar Energy Without You Even Knowing It’s There

Researchers are developing transparent solar collectors that let sunlight in, while turning ultraviolet and near-infrared light into electricity

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/81/4a817469-8931-44dc-8c1d-22451790f30c/transparent_solar_concentrator.jpg)

If we stand any chance of reversing or even slowing climate change, we’re going to need all the clean energy we can get. Solar could potentially be a big slice of the power pie. But particularly in large cities, where power consumption is high, there isn’t a lot of open space to set up massive solar farms—for instance, the Ivanpah Solar Electric Generating System takes up 3,500 acres of California’s Mojave Desert.

Energy can be brought in fairly easily from areas outside cities. But solar efficiency has physical limits, so utilizing all available space for energy production is important. And while city rooftops leave some room for solar panels, that space could instead be used to grow local food in temperate climates.

There are plenty of potentially energy-generating windows in high-rises and skyscrapers, though.

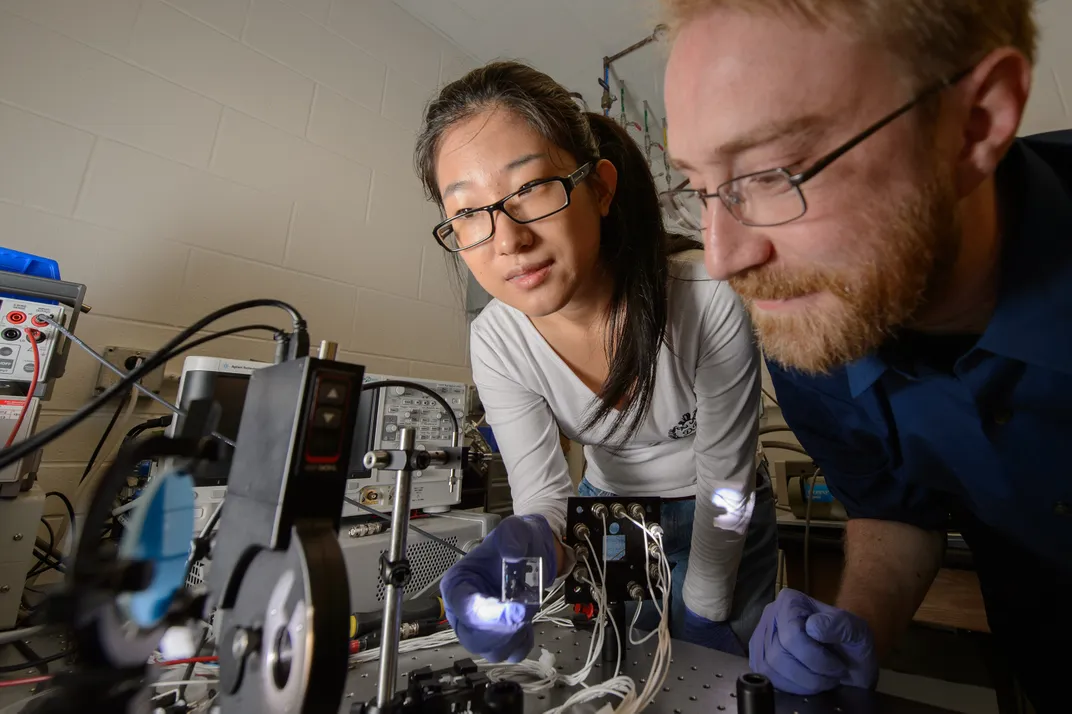

Researchers at Michigan State University have developed clear plastic solar collectors that can be placed on windows without obstructing the view. The same collectors can adhere to the screens of mobile devices as well. According to a recent paper in the journal Advanced Optical Materials, the plastic lets through all visible light. The solar-collecting windows won’t appear tinted or cloudy to the human eye. Instead, the material is embedded with tiny fluorescent organic salt molecules, which have been engineered to absorb only parts of the light spectrum that people can’t see, such as ultraviolet and near-infrared light.

Richard Lunt, an assistant professor at Michigan State and one of the paper’s authors, says the molecules are similar to those found in nature, just slightly tweaked. “We tailor them to suit our needs,” he writes in an email. “That is to harvest particular components on the invisible solar spectrum and glow at another wavelength in the infrared.” That infrared “glow” is then picked up by strips of photovoltaic cells (essentially tiny solar panels) at the edge of the material and turned into electricity. From there, the wired-up windows could shunt the harvested energy to local batteries or back into the electrical grid.

The transparent solar collector still needs a fair bit of refining, as its efficiency is relatively low: just 1 percent of the ultraviolet and near-infrared light is converted into electricity. Most commercial solar panels today are between 15 and 20 percent efficient. But Lund thinks the technology should reach 5 percent or higher with further research.

“We are actively exploring routes to improve efficiency by improving the 'glowing' efficiency, expanding the absorption range of the infrared spectrum,” writes Lunt. He also says further tuning the interactions between the light-collecting molecules and transparent material they're embedded in should increase the amount of energy collected.

Lunt says the basic idea of luminescent solar collectors has been around for decades. But, unlike other projects, this work aims to harvest non-visible light. He claims they can be made using standard industrial processing, and they only require a small amount of solar cells at the edge of the material to collect the energy optically. That means they should be fairly inexpensive to produce. The fact that they can be installed on the existing infrastructure of buildings and windows should also reduce the cost versus standalone solar panels.

Lunt thinks it’s likely, though, that the technology will show up in small electronics first, because it already produces enough energy to power things like e-readers and smart windows. The team has founded a company, Ubiquitous Energy, Inc., which is working on commercializing the technology. They expect to see their transparent solar collectors on buildings and mobile electronics within the next five years.

The professor doesn’t think the potential applications stop there, either, noting that the tech can be used on other glass surfaces, such as car windshields.

“You can even think about putting these devices over surfaces where you care about maintaining certain aesthetics or patterns, like siding, textiles or even billboards,” writes Lunt. “They could be all around us without even knowing they are there.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/unnamed.jpg)