Transparent Mice Let Researchers See Cancer Spread in Real Time

By making organs transparent, researchers at Tokyo University can spot individual cancer cells

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/68/35/683598a9-8896-485f-b78f-36ca99c5b48e/161116_renca-mcherry_reddot2_body.jpg)

One of the scariest things about cancer is the way it spreads, with cancerous cells breaking free and spreading throughout the body, landing in other organs and beginning to grow there. The process, known as metastasis, is often a death sentence, the point where the best cancer-fighting techniques become ineffective. But it’s tricky to follow; we lack a means of imaging whole systems at the detail needed to spot a few elusive metastasizing cells.

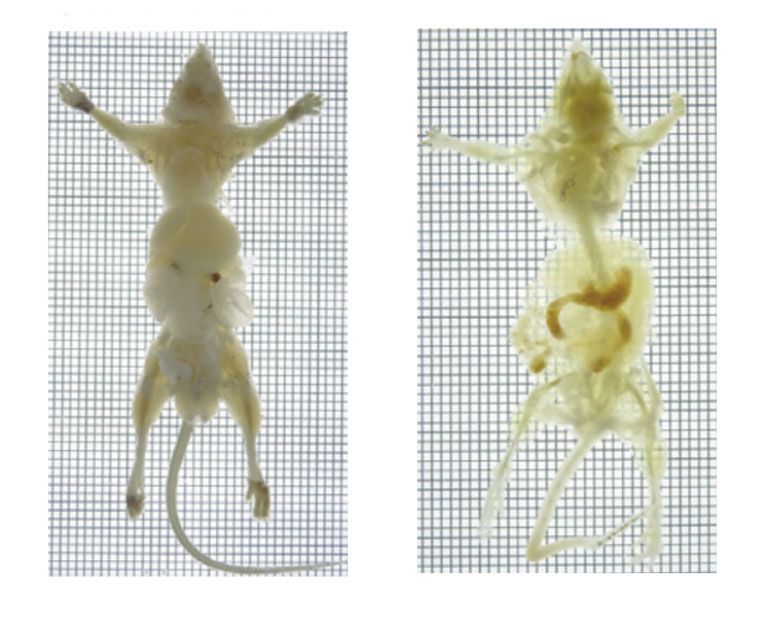

To that end, scientists at the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Medicine have developed a method of imaging, published in the journal Cell Reports, that shows metastasis in real time, at the level of individual cells. The technique relies on modified cancer cells that glow and a chemical cocktail that turns organs transparent, making the fluorescent signals emitted by the modified cells easier to see. This, in turn, can offer a more comprehensive view and a better understanding of metastasis that researchers could use to develop better drugs.

“One of the difficulty in analysis of the cancer metastasis is, it spreads anywhere in the body,” says Hiroki Ueda, a pharmacology professor who worked on the study. “It goes to the brain, or the pancreas, or kidney. To understand the whole picture of the metastasis, whole body analysis with high resolution … is quite important.”

As cancer metastasizes, any of those cells floating around the system can become a growth. And it’s important to catch them all. Like bacteria that develop resistance to antibiotics, treating cancer with chemotherapy can leave isolated cells or colonies behind, and those are then liable to become drug-resistant strongholds. Making the process visible in research could help scientists understand what types of cancer cells are likely to form what they call “malignant outposts,” and help design drugs specifically to combat them.

Tissue clearing—the process of making cells more translucent—was invented around a century ago, and has been used in imaging for cancer research, bacterial infections, and autoimmune diseases for more than a decade. Ueda, his collaborator Kohei Miyazono, and their team developed a different, two-stage chemical cocktail that improves the detail over the old method. To make it easier to image the organs, the researchers needed light to flow straight through the tissue, without refracting too much due to different tissue densities. The first stage reduces lipids, which refract light a lot, and the second stage increases the refraction in the organs' surroundings, to better match it to the organ, allowing the light to pass cleanly through. The process results in a visualization clear enough that researchers can see individual cancer cells.

To test the method, Ueda and Miyazono injected cancer cells into mice, and euthanized them at different stages. The detail due to the clearing allowed them to see individual cells in the tissue of various organs, including brain, lungs, liver, and intestines. Theoretically, points out Ueda, you could see the cancer cells with another technique, 2D histology, in which fine slices of organs are examined for cancerous cells, but the time required to view enough slices of each organ is prohibitive. Tissue clearing, in combination with in vivo bioluminescence, allows a three-dimensional scan of a whole organ, or a whole body, very quickly.

At this point, this technique is really only useful in research, points out Takeshi Imai, a professor of neurophysiology at Kyushu University’s Graduate School of Medical Sciences, who was not involved with the study. That's because the process kills the tissues it works on, and because normal cancer cells don't fluoresce. But it should still be useful, he added. “If you use mouse models, you can investigate distribution of cancer cells at whole-body scale, which should be useful to study cancer metastasis … as well as the action of cancer drugs,” he says. “Previously, pathological examinations were only performed on thin slices of tissues.”

But clearing could one day be used in biopsies, where a portion of tissue is removed. And if the method could be refined, there’s a possibility it could work in live subjects.

“In the future, near future, maybe this kind of technique can be applied to not only animal research, but also human clinical studies or operations,” says Ueda.