An Underwater Museum in Egypt Could Bring Thousands of Sunken Relics Into View

The proposed site might revive tourism in Alexandria and also further research into the ancient ruins

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7e/5b/7e5b9a77-ce5b-4fb6-9dee-f881ac59af36/alexandria-underwater-museum.jpg)

The Great Sphinx, the pyramids at Giza, the temples at Luxor—if you’ve been to Egypt, you’ve probably seen them. Next time, you might try putting the Lighthouse of Pharos on your Egyptian bucket list, and don’t worry that it’s at the bottom of a harbor. A new museum proposed for Egypt’s City of Alexandria aims to bring visitors to sunken treasures not seen by the public in over 1,400 years.

In the works since 1996, the plan to build an underwater museum in the Eastern Harbor area of Alexandria’s Abu Qir Bay has again been revived. Mamdouh al-Damaty, Egypt’s minister of antiquities, announced in September that the country was once again prepared to move forward with the ambitious scheme.

“This area was one of the most important areas in the world for around 1,000 years,” says Mohamed Abd El-Maguid, the head of the department of underwater activities at the Ministry of Antiquities. “In five meters of water, we have these remains of palaces and temples, but nothing people can see with their own eyes. Having a museum like this will attract more tourists that will help the economy move again.”

The idea for an underwater museum first came to the table 20 years ago, when Egyptian officials began studying how to better protect the valuable artifacts in Alexandria from further degradation. At the moment, relics are under threat by pollution in the bay, poaching by divers and damage by fishing boat anchors. A museum would help safeguard the remaining relics not only as a physical structure, but also as a protected area that could be monitored, El-Maguid says.

After 1997, UNESCO got involved, helping to define a potential museum project. In 2006, stakeholders convened at a roundtable workshop to further refine the project’s goals, but everything was put on hold in 2011 after the January 25 Revolution and ensuing political upheaval. Talks resumed in 2013.

El-Maguid had a meeting with al-Damaty this past September during which he says the minister affirmed the commitment to build an underwater museum in Alexandria, and that he anticipates site feasibility studies will start as soon as funding is secured. The Egyptian government, strapped for cash, isn’t expected to contribute any money towards the project, El-Maguid says, but private entities have expressed an interest in possibly helping out, including Chinese corporations. According to a policy report by the Centre for Chinese Studies at Stellenboch University in South Africa, Hutchison Whampoa and other Chinese companies have already made significant investments in Egypt’s infrastructure and port redevelopment projects.

“The Chinese are coming in force,” El-Maguid says. “But part of the feasibility study would be how to finance the museum.”

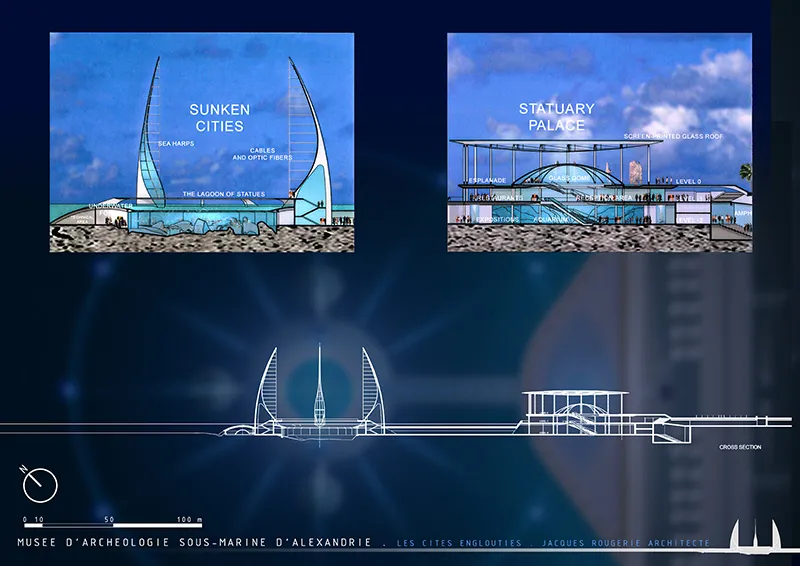

In 2008, French architect Jacques Rougerie caught wind of the project and reached out to the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities to offer his services to create conceptual renderings. What resulted is a spellbinding design that evokes a sense of Egypt’s deep connection to the past.

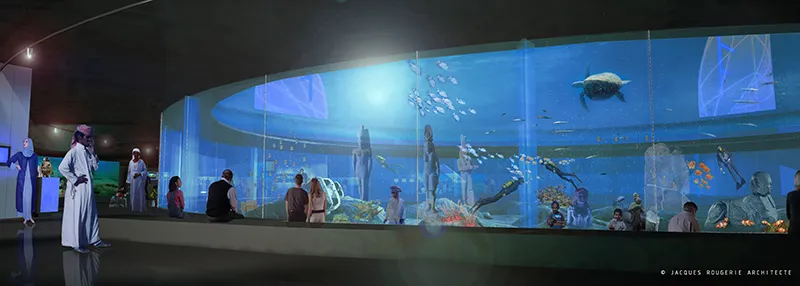

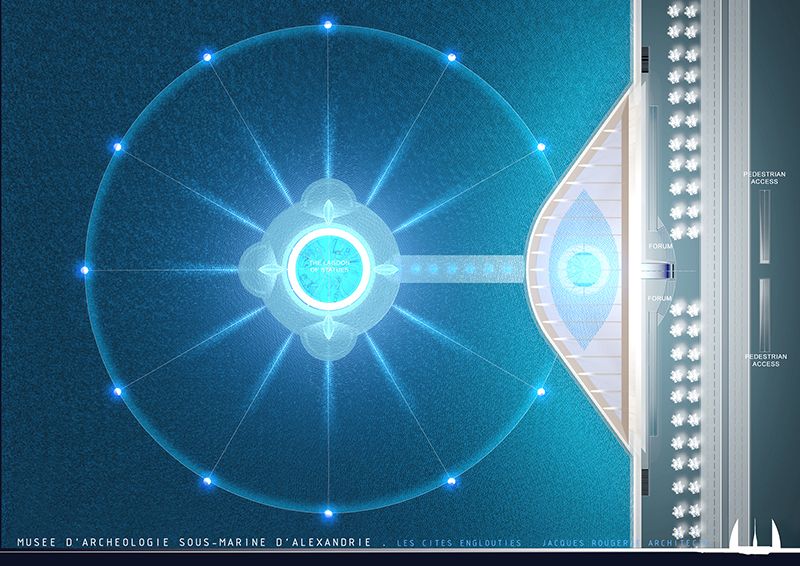

Rougerie’s design features an inland building on the shores of the Eastern Harbor of Abukir Bay, connected to a submerged structure in the water. A series of fiberglass tunnels brings visitors to the sea floor, some 20 feet below the surface, where more than 2,500 relics stand. Some, like the massive blocks that are believed to be the remains of the once 450-foot-tall Pharos lighthouse, which was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World before tumbling into the bay in the 13th century A.D., are partially buried.

Topped by four tall edifices shaped like the sails of a felucca, the traditional wooden sailboat of the Nile, Rougerie’s design would allow visitors to see the artifacts as they’ve stood for centuries, including what are thought to be the remains of Cleopatra VII’s palace—she of Shakespearean tragedy—as well as busts of her son, Caesarion, and her father, Ptolemy XII. Rougerie estimates construction would take about two years, plus time required to complete site surveys and planning.

“[A] long walkway opens under an immense aquatic space, inundated with sun and dancing flashes of an incredible collection of statues and relics in the Alexandria Bay and in Abu Qir,” Rougerie explains in a video that demonstrates his concept. “These moving signs from the past are enhanced by a scenography that combines the magic and beauty of the underwater world.”

Rougerie cites Jules Verne as the inspiration for much of his work, which includes underwater habitats, marine laboratories and research centers. He’s also put forward proposals to build some pretty fantastical designs, including the floating city of Mériens, shaped like a manta ray, and the SeaOrbiter, a half-submarine half-skyscraper intended to allow researchers to cruise and study the seas 24/7. The designs are intentionally pelagic and alien—by building structures reminiscent of sea life, Rougerie works to draw attention to the “beauty and fragility of the sea and its fundamental role in the story of humanity,” according to his website.

Rougerie says that a museum of this type in Alexandria would not only help revive tourism in the city, but also help facilitate further research into the ruins there. A final design will be solicited and chosen following further feasibility studies.

“We envisioned an underwater archaeology school with an international resonance to be part of the museum’s facilities,” Rougerie says. “The public could assist the work of the archaeologists on archaeological treasures like Cleopatra’s palace or the royal court that have been hidden from the public for thousands of years.”

Scholars still debate when and how Alexandria’s once-great palaces, lecture halls, homes and temples came to be submerged. In part through studies of sediment cores in the bay and excavations of remains beneath present-day Alexandria, it seems to have been a slow destruction wrought by earthquakes, tsunamis and gnawing erosion by the sea. It’s very possible the waters of the eastern Mediterranean Sea gradually inundated the city between the 6th and 7th centuries A.D.

The treasures there have been remarkably well preserved over the ensuing 14 centuries, even in relatively polluted water and despite a 1993 breakwater construction project that is thought to have destroyed many artifacts by accident. Recent dives by French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio have revealed statues with the faces of Ptolemy and Cleopatra, falcon-headed crocodile sphinxes and priests holding canopic jars.

Ulrike Guérin is an UNESCO attorney responsible for the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, an agreement by UN member nations to strengthen the safeguarding and conservation of valuable submerged artifacts in their waters.

Guerin says she expects two or three years to pass before any real movement begins. But she adds the successful construction of a museum in Abu Qir Bay would change the landscape of research and education into the archaeological remains of an important part of Egypt’s history.

“This kind of museum could change the way we look at underwater heritage,” Guérin says. “It’s difficult, because you can’t go there, and it’s a real issue to see that authentic heritage without having to take it out and dry it up. You can never show all of Alexandria—it’s huge—but parts of it are mind-changing.”

Though it may be more logistically simple to exhume some of the artifacts and install them in an aboveground museum, El-Maguid says the fact that they’re underwater offers Egypt a chance at creating a completely new kind of museum to add to the collection of 37 land-based museums that already exist in the country.

“Fixed remains, like the pediments of the large buildings, can’t be taken out,” El-Maguid says. “We also have more than 2 million objects in Egypt, all above ground. If we were to take these out of the water, what would be the difference? Here we have something new.”

No other museum like this currently exists, though a smaller, proof-of-concept version of an underwater museum exists in China at the Baiheliang Underwater Museum near the Three Gorges Dam on the Yangtze River. Featuring concrete-clad tunnels with portholes, visitors can catch a glimpse of seven-foot-long carved stone fish that once helped measure river level changes.

In the meantime, UNESCO continues with plans to create several online exhibitions of underwater sites, such as at Pavlopetri in Greece. A project is underway to create a virtual recreation of the city’s ruins through photography and 3D scans.

“The underwater realm is a mystery, and underwater archaeology is also a mystery, so you have a mystery squared,” El-Maguid says. “If you cannot see, you cannot understand, and if you cannot understand, you cannot appreciate. We’re trying to draw attention to what we have here, keep it as intact as possible, make it available for everyone and try to add chapters to the history books.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Michelle-Donahue.jpg)