You Can Now 3D Print Glass

German researchers have developed a technique for 3D printing strong, transparent glass products, such as jewelry, lenses and computer parts

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1f/e8/1fe82a35-a77e-496f-9246-bc36d03d831b/3dprintedhoneycomp2.jpg)

Hamburg’s new concert hall opened late last year to acclaim from architectural critics around the world. The soaring structure has a façade of some 2,000 flat and curved glass panels, giving the impression of a wave about to break. But the project was six years late and hundreds of millions of euros over budget, with some of the overage due to the ancient, time-consuming molding technique used to curve the glass panels.

But what if the glass panels could simply have been printed with a 3D printer?

Until now, this wouldn’t have been possible at all. The most commonly used 3D printing materials are polymers, and techniques exist for printing metals, ceramics, concrete, medication, even food as well. But glass has been almost absent from the equation.

“Glass is one of the oldest materials that mankind has used, and it’s astonishing to see the 3D printing revolution of the 21st century has ignored glass until now,” says Bastian Rapp, a researcher at Germany’s Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.

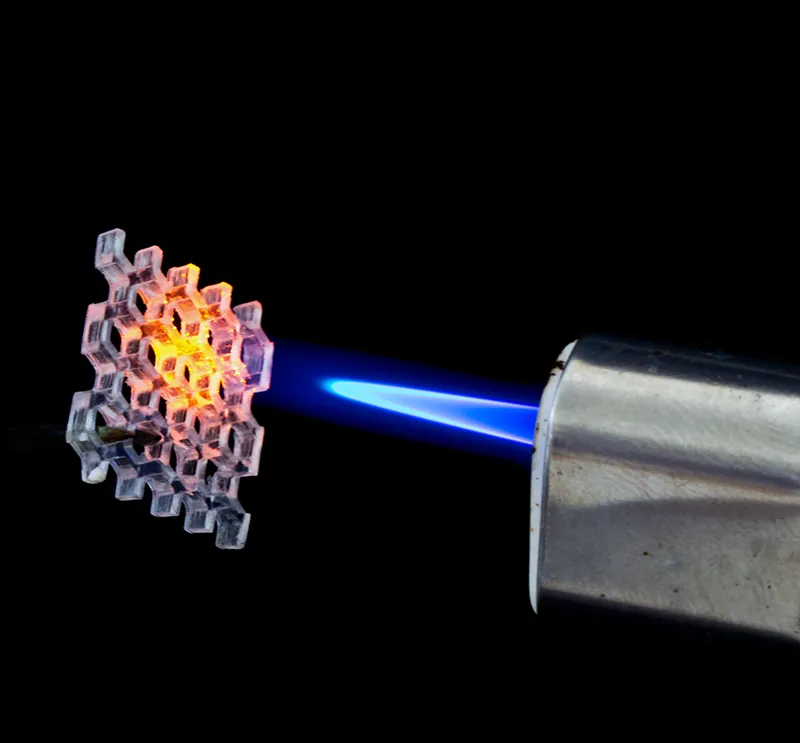

Rapp’s team has come up with a new technique for 3D printing glass, one which can produce glass objects that are both strong and transparent. The technique makes use of a traditional method of 3D printing called stereolithography. In stereolithography, the printer builds up the object layer by layer using a liquid—traditionally a polymer—that hardens when touched by a laser light. Rapp’s team has figured out how to do this using powdered glass suspended in a liquid polymer. Once the object is printed, it’s placed in a high temperature oven, which burns away the polymer and fuses the glass particles, leaving behind only hardened glass.

Though Rapp’s technique isn’t the first example of 3D printing glass—MIT researchers developed a method for extruding molten glass two years ago, while other teams have used lower-temperature techniques that produce a weak, cloudy product—it is the first to print clear glass at low temperatures. It’s also the first to take advantage of ordinary, off-the-shelf 3D stereolithography printers, meaning it can be used without much special equipment.

Glass has a number of unique properties that make it desirable as a 3D printed material, Rapp says.

“There is almost no material that can be exposed to such high temperatures as glass can be exposed to,” he says. “And there is almost no chemical that can attack glass, whereas polymers can be degraded by UV light and organic solvents.”

Glass also has a transparency unmatched by other materials. Light doesn’t pass nearly as well through even the clearest plastics, which is the reason houses have glass windows, despite their breakability. High quality camera lenses are always glass for this reason, Rapp says, while smartphones’ lenses are usually plastic.

“This is why the quality of the photo you take with a state of the art smartphone as compared with a camera is always inferior,” Rapp says.

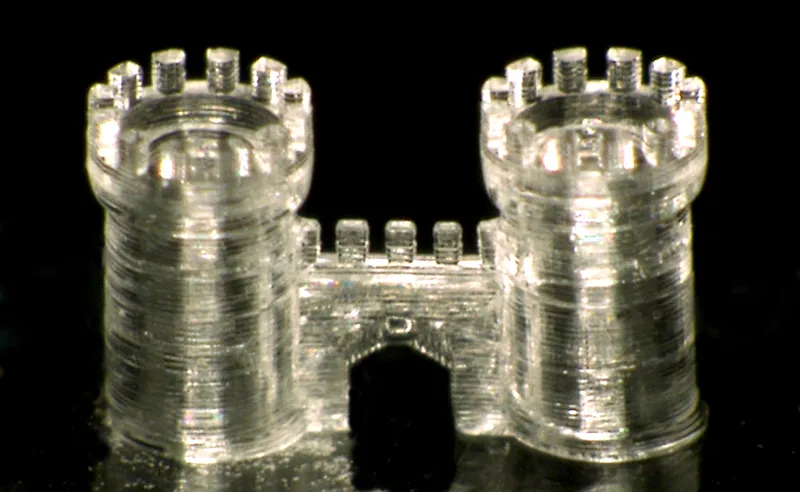

The new technique could be used to print almost anything, Rapp says. It could be used for tiny, intricate objects like jewelry, lenses or computer parts, or for large objects such as windows. The only variable is the printer itself.

The 3D printing technique has advantages over non-printing methods of making small glass models in that it doesn’t require chemical etching, which uses dangerous hydrofluoric acid, and that it can have closed cavities and channels, which isn’t possible in traditional glass-blowing. And it potentially has a speed advantage over non-printing methods of glass production as well.

For their research, Rapp’s team used an inexpensive, unmodified printer of a type that could be bought by any home enthusiast.

“It’s a well-established technological platform in terms of machinery, and it’s a well-recognized and well-known material,” Rapp says. “The only thing we made was the bridge in between.”

The team’s research was published this month in the journal Nature.

Rapp has created a company to commercialize the technique. He hopes to have a first product on the market by the end of the year.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/matchar.png)