A Gibson Girl in New Guinea

Two Seattle women have retraced the travels of Caroline Mytinger, who journeyed to the South Sea islands in the 1920s to capture “vanishing primitives”

In the 1920s, New Guinea and the Solomon Islands were among the world’s last wild places. Largely unmapped and inhabited by headhunters and cannibals, the jungle isles of the Coral Sea captured the popular imagination as exemplars of the unknown. Dozens of adventurers took up the challenge posed by these remote lands, but perhaps the least likely were two young American women who set out from San Francisco in 1926 armed with little more than art supplies and a ukulele.

Caroline Mytinger, a 29-year-old Gibson girl turned society portraitist, undertook the expedition in hopes, she wrote, of realizing her dream of recording “vanishing primitives” with her paints and brushes. She convinced a long-time friend, Margaret Warner, to accompany her on what became a four-year journey throughout the South Seas.

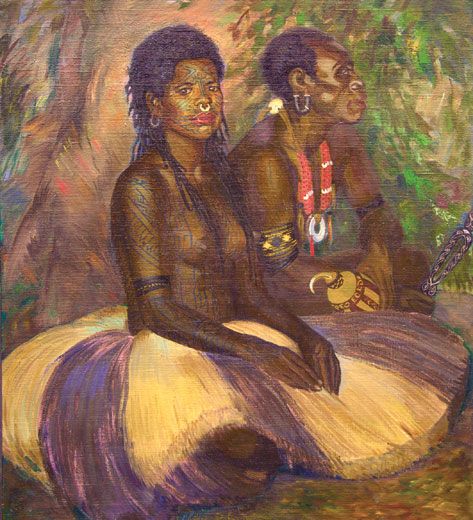

When the two women finally made it back to the United States in the winter of 1929, they were in poor health, but they came bearing treasure: more than two dozen of Mytinger's vivid oils of the region’s peoples, plus dozens of sketches and photographs. The paintings were exhibited at New York City’s American Museum of Natural History, the Brooklyn Museum and other museums around the country in the 1930s, and during the next decade Mytinger recorded her adventures in two bestselling books illustrated with her artwork.

The recognition Mytinger won proved fleeting, however. She returned to making portraits of society matrons and their children, her books went out of print and her South Seas paintings disappeared into storage. For decades, even well before her death in 1980 at the age of 83, both she and her work had been forgotten by the wider world.

That might still be the case if it weren’t for another pair of adventurous American women. A gift of one of Mytinger’s books in 1994 inspired Seattle-based photographers Michele Westmorland and Karen Huntt to spend several years and raise some $300,000 mounting an expedition to retrace Mytinger’s original South Seas journey.

They also tracked down most of Mytinger’s island paintings, the bulk of which are now housed in the archives of the University of California’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology in Berkeley. Today these pictures evoke the mystery and allure of two distant worlds—the exotic peoples that Mytinger set out to document and the reckless optimism of 1920s America. That era of flappers, flagpole sitters and barnstormers is perhaps the only time that could have produced an expedition at once so ambitious and so foolhardy.

When Mytinger and Warner sailed through the Golden Gate on a foggy day in March 1926, they were unencumbered, Mytinger later wrote, “by the usual equipment of expeditions: by endowment funds, by precedents, doubts, supplies, an expedition yacht or airplane, by even the blessings or belief of our friends and families, who said we couldn’t do it.” They had only $400—“a reserve fund to ‘ship the bodies home,’” as Mytinger put it—and plans to cover expenses by making portraits of local white colonials. The rest of their time would be spent, she said, “headhunting” for native models.

The young women had already used a similar earn-as-you-go method to travel around the United States, with Mytinger bringing in the money by making portraits while Warner entertained the portrait sitters, playing them songs on her ukulele and, Mytinger recounted, “generally keeping everyone awake in the pose.”

When the two adventurers left San Francisco, their goal was to head to the Solomon Islands and then New Guinea, but their low-budget mode of travel dictated a circuitous route that took them first to Hawaii, New Zealand and Australia. Along the way, they snagged as many portrait commissions as they could and hitched free rides on passing boats whenever possible.

Once they reached the Solomons, the women met with what less daring souls might have regarded as excellent reasons to abandon their journey. Mytinger’s case of art supplies fell into the ocean when it was being transferred to a launch bringing them from one Guadalcanal settlement to another. The remoteness of the islands defied Mytinger’s efforts to order replacements, so she had to make do with boat paint and sail canvas. Both women also contracted malaria and fell victim to a host of other tropical ailments, including, Mytinger reported, “jungle rot” and “Shanghai feet,” as well as attacks by cockroaches and stinging ants.

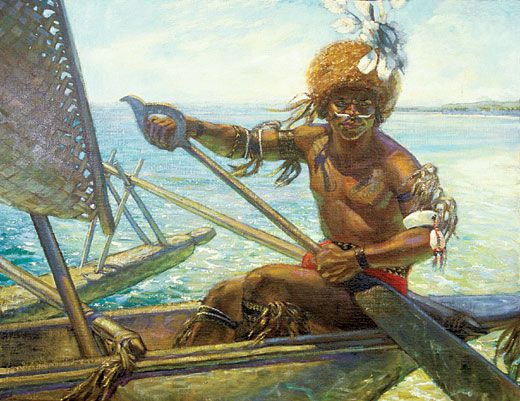

But these were minor annoyances to the pair, who by all accounts gloried in exploring the strangeness and beauty of the exotic isles and their peoples. In her paintings and drawings, Mytinger depicted men, women and children of the coastal fishing tribes as well as members of the bush tribes living deep in the jungle. She recorded native dress and customs, the indigenous architecture of vine-and-bamboo huts and the men’s elaborate hairdos—bleached with lime (to kill lice) and decorated with feathers, flowers and live butterflies.

In the Solomon Islands in the village of Patutiva, the two Americans were the only women invited on a hunt for giant turtles. “There seemed to be acres of great brown shells floating on the water,” Mytinger recalled. “The whole surface was covered far out ahead with waving islands of them.” The hunters slipped into the water, turned the slumbering turtles onto their backs (rendering them helpless) and pulled them onto shore with their boats. Days of riotous feasting followed, in a scene that Mytinger wrote was “the picture of Melanesia: the smoky shafts of sunlight...; the billions of flies; the racing dogs and yipping children; the laughter and whacking and the wonderful color of great bowls of golden [turtle] eggs on the green banana-leaf carpet.”

After surviving an earthquake in Rabaul and producing a stack of canvases depicting the Coral Sea peoples, Mytinger and Warner moved on—by wangling rides on a series of small boats—to what is now Papua New Guinea. They spent many months hopping from settlement to settlement along the coastline, sometimes through terrifying storms. Mytinger described one night voyage in a leaky launch whose engine stalled during a ferocious downpour; only frantic paddling with wooden slats ripped from the boat’s engine cover saved them from being swept into the surf. “I do not know why it seems so much worse to drown on a dark night than in the daylight,” Mytinger later wrote.

Despite such brushes with disaster, the two eagerly seized the opportunity to travel into New Guinea’s still largely unexplored interior on the launch of an American sugar-cane expedition going up the island’s Fly River. Mytinger and Warner went ashore several times, often against the advice of their companions. On one occasion, they were charged by a gigantic lizard. On another, in the remote village of Weriadai, they were confronted by indignant tribesmen when they managed to sneak away from the colonial government representative and the Papuan troops who were escorting them and finagle their way into a women’s “longhouse”—a gathering place strictly taboo to outsiders. When the government representative arrived with the Papuan Army “and a vociferously protesting crowd of tribesmen,” Mytinger recounted, “we gals were all sitting chummily on the floor inside the longhouse, the clay-plastered Weriadai matrons acquiring charm by smoking Old Golds and Margaret and I yodeling the Hawaiian ‘Piercing Wind.’” Mytinger got the sketches and photographs she wanted, the Weriadai women got to one-up their men with the Americans’ cigarettes, and the government representative eventually thanked the two women for helping to promote “friendly relations."

Mytinger’s adventurous streak ran in the family. Her father, Lewis Mytinger, a tinkerer whose inventions included a can opener and a machine for washing gold ore, had already shed one family when he married Orlese McDowell in 1895 and settled in Sacramento, California. But within two years—just four days after Caroline was born on March 6, 1897—Lewis was writing to a sister to ask for help finding an old girlfriend. “You know,” he wrote, “I might take a notion to marry again some day and it is good to have a great many to select from.” Caroline was named after another sister, but that seems to have been the extent of his family feeling. Not long after her birth he took off for the gold fields of Alaska, where, according to family records, he accidentally drowned in the Klutina River in 1898.

Young Caroline and her mother moved to Cleveland, Ohio, where Caroline grew up and attended the Cleveland School of Art from 1916 to 1919. Through an art school classmate she rediscovered her namesake, her aunt Caroline, who lived in Washington, D.C. In a letter to her newfound relative, the 21-year-old described herself as “tall and thin,” adding, “I appear to have large feet and orange tresses, which hang around most of the time and make me look like a beastly flamboyant poodle.”

Mytinger was in fact a strikingly lovely strawberry blonde who was known as “Cleveland’s most beautiful woman.” She paid for her art lessons, first in Cleveland and later in New York City, by posing for several distinguished artists, among them illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, who used her as a model for some of his famous Gibson girls. Within a few years of completing school, Mytinger was earning her living painting portraits of local socialites and doing illustrations for Secrets magazine, turning out dewy-eyed beauties to accompany such articles as “When My Dreams Come True.”

In December 1920, she married a young Cleveland doctor, George Stober. According to the standard script, it was time for Mytinger to settle into cozy domesticity. She had other ambitions, however, and they reflected the crosscurrents of social change that characterized her era.

Mytinger was part of a generation of American women who in unprecedented numbers sheared off their hair, shortened their skirts and went to work outside the home. Some went farther: during the Roaring Twenties, books and magazines detailed the exploits of “lady explorers.” At the same time, World War I and a huge influx of immigrants had dramatically increased American awareness of cultural differences. Along with people who regarded those differences as threatening, there were idealists eager to investigate other cultures as a way of questioning their own. During the 1920s, anthropologist Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa became a top-seller and Chicago’s Field Museum sent artist Malvina Hoffman around the world to create some 100 life-size sculptures illustrating the world’s “racial types.”

Mytinger read every anthropology text she could find and hoped her talent for portraiture could contribute to social science. She started out, according to one newspaper account, by trying to record “the various Negro types” in Cleveland, then went to Haiti and to Indian reservations in Florida and California. But since none of the peoples she encountered represented the “pure types” she said she wanted to paint, she hit upon the idea of going to the relatively unexplored Solomon Islands and New Guinea.

By then, Mytinger’s marriage appears to have ended, although no record has been found that she and Stober ever divorced. She apparently traveled under the name of Mrs. Caroline Stober, which is perhaps why Warner was the recipient of at least five proposals from lonely South Seas colonials, while Mytinger doesn’t mention receiving any herself. She never married again, but she kept a letter from Stober, undated, that reads in part, “Dear wife and darling girl.... If I have been selfish it has been because I have been unable to suppress my emotions and did not want you away from me.” Some seven years after Mytinger returned from New Guinea, she wrote to her aunt Caroline that she had left her husband “not because he was a disagreeable person, but because...I would never live in the conventional groove of matrimony.”

The long letters Mytinger wrote to friends and family during her travels in the South Seas formed the basis of her two books. Headhunting in the Solomon Islands was published in 1942, just as those islands became suddenly famous as the site of fierce fighting between U.S. and Japanese troops. Mytinger’s true-life adventure story was named a Book-of-the-Month Club selection and spent weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. Her second book, New Guinea Headhunt, came out in 1946, also to excellent reviews. “New Guinea Headhunt,” wrote a critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, “is top-of-the-best-seller-list reading for the unexpected incidents in it that are the stuff of first-rate narration.” More than half a century later, her two volumes remain captivating reading, thanks to her lively descriptions of the people and places she and Warner encountered. But some of Mytinger’s language, while all too common in her own time, strikes an ugly note today. Her use of terms such as “darky” and “primitive” and her references to children as “pickaninnies” will make modern readers cringe.

Yet she also cast a critical eye on white exploitation of local labor (men were typically indentured for stretches of three years on both coconut and rubber plantations for wages of just $30 a year) and on the affectations required to uphold “white prestige.” Despite white settlers’ complaints about the “primitives’” savagery and stupidity, Mytinger wrote that she found them “polite and clean, and certainly far from stupid. That we could not understand their kind of intelligence did not prove that it did not exist and was not equal to our own in its own way.”

Some of Mytinger’s most challenging encounters came as she and Warner searched for models among peoples who had no concept of portraiture and considerable suspicions about what the two foreigners might be up to. Mytinger describes a “raw swamp woman” named Derivo who had been drafted to serve as housemaid to the Americans during their visit to a remote station along the Fly River. They convinced her to pose in her short grass skirt and palm-leaf hood, virtually the only clothing native women wore in that rainy country. But Derivo became increasingly fidgety and unhappy, and it finally came out, Mytinger wrote, that the woman believed “this painting business was making her legs sick.” No sooner had Derivo stopped posing, the picture unfinished, than she was bitten on the buttocks by a poisonous snake. She recovered, Mytinger reported, but the “episode put us in bad odor in the community, and for a while we could get no other woman to pose for the unfinished figure.”

The same Fly River station also produced Mytinger’s favorite model, a headhunter named Tauparaupi, whose portrait is on the cover of the artist’s second book (p. 80). He was brought to her as part of a group that had been taken prisoner by the authorities for allegedly beheading and eating 39 members of a neighboring village. Two other sitters were the protagonists in a Papuan tragedy. One painting showed a pretty girl named Ninoa being readied for a ceremonial dance by her mother, who carried the girl’s tiny baby on her back. Another canvas depicted two young men smoking a native pipe. One of the men was the father of Ninoa’s baby, but he refused to marry her and, worse, publicly laughed at her while she was being painted. She left and hanged herself in one of the huts, not out of sorrow but to revenge herself by haunting her disloyal lover. Shortly thereafter, Mytinger wrote, “Ninoa let him have it” when the young man was seriously injured in an accident.

Mytinger often captured details beyond the reach of the era’s black-and-white photography—the colors of a massive feather headdress, the subtleties of full-body tattooing and the bright stripes dyed into the women’s grass skirts. At the same time, her renderings gave full expression to her models’ humanity. But some of Mytinger’s depictions are not entirely sound from an anthropological point of view. For example, while painting a young New Guinea man with elaborate decorative scarring on his back, Mytinger, using pidgin English and sign language, invited him to adorn himself with appropriate items from the local museum. Long after the portrait was completed, she learned that the hat the man had chosen to wear came from a district other than his own and that the pink-and-blue-painted shield he held was actually from New Britain Island. “After that discovery,” Mytinger concluded, “the only thing we could be sure was authentic in the picture was the hide of the boy himself.”

Moreover, Mytinger’s style and training made a certain amount of idealization of her subjects all but inevitable. A surviving photograph of two of Mytinger’s New Guinea subjects, an older man nicknamed Sarli and his younger wife, reveals marked disparities between the woman’s pinched and disheveled appearance in the photo and her painted countenance. (Sadly, both soon died from a strain of influenza carried to their village by the crew of a visiting American freighter.)

After three years in the tropics, Mytinger and Warner were ready for home. But they had only enough money to get to Java, where they lived for almost a year, rebuilding their health while Mytinger repainted her pictures with real oil paints. Finally a job doing illustrations brought in enough money to get them both back to the United States.

Not long after the two women arrived in Manhattan, the city’s American Museum of Natural History exhibited Mytinger’s paintings. “Glowing with rich hues, vigorously and surely modeled,” wrote a critic for the New York Herald Tribune, “these paintings reveal, as no flat black-and-white photographs could, the actual gradations in the color of hair, eyes and skin of the various South Sea Island tribes...and the vividness of their decorations and natural backgrounds.” The pictures next went on display at the Brooklyn Museum and then traveled to the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art. Newspaper reporters eagerly wrote up the story of Mytinger’s expedition, but the country was deep in an economic depression and no museum offered to buy the pictures. “The paintings are still orphaned at the Los Angeles Museum,” Mytinger wrote to her aunt Caroline in 1932. “Sometime when the finances of the art buying public are restored to normalcy, I may be able to get something for them—but I know it isn’t possible now.”

Mytinger resumed her career as an itinerant portraitist, traveling to Louisiana, Iowa, Ohio, Washington—wherever commissions could be found. Sometimes a local museum showed her South Seas paintings, but by the 1940s she had packed the pictures away. Some of Mytinger’s clients were prominent—members of the Weyerhaeuser timber dynasty, the flour company Pillsburys, novelist Mary Ellen Chase, whose Mytinger portrait still hangs in one of the libraries at Smith College in Massachusetts—but most were not. “I’m not writing and not painting,” Mytinger’s 1932 letter continued, “just pounding out these small drawings for which I charge twenty-five dollars—and being grateful for orders.”

Her financial ambitions were modest. “I like not having much money,” she wrote to her aunt in 1937. “I like the feeling that I charge for my pictures only what I think they are worth and not as much as I could get. It gives me a feeling of great independence and integrity, but it also produces a large amount of inconvenience when I want things that are in the capitalist class—like real estate.” A home of her own, however, came with the publication of her first book in 1942. The following year, she bought a one-bedroom studio in the California coast town of Monterey, a well-known artists’ community. By then she and Warner seem to have gone their separate ways. “Hope you like living alone as much as I do,” Mytinger wrote to a cousin. “I treasure it.” She remained there for the rest of her life.

In her later years Mytinger lived frugally and painted for her own pleasure, traveling occasionally, enjoying her dogs and cats, entertaining friends and tinkering around her house, which was filled with mosaics, handmade furniture and other results of her handiwork. It appears she walked away from her time in the limelight with relief rather than regret. “She hated careerism and galleries and the ego presentation,” says Ina Kozel, a younger artist whom Mytinger befriended. “She definitely was an artist through and through, in her soul and in the way she lived.”

Although Mytinger traveled to Mexico and Japan in the 1950s and ’60s, and drew and painted studies of the local peoples there, she did not keep those pictures. It was the South Seas paintings that she preserved and kept until a few years before she died. And it is no accident that she gave them to an anthropology—not an art—museum.

As early as 1937 she had begun to question the aesthetic quality of her work. “I will never be a real artist,” she wrote to her aunt Caroline. On the evidence of the handful of Mytinger’s stateside portraits that have been located, her self-criticism is not far off the mark. They are workmanlike but a bit anemic, painted with skill but not, perhaps, passion. The paintings from the South Seas, by contrast, are far bolder and more intense, with stunning use of color.

In Headhunting in the Solomon Islands, Mytinger lamented that “though we had set out with the very clear intention of painting not savages but fellow human beings, the natives had somehow, in spite of us, remained strangers, curiosities.” Perhaps that was unavoidable, given the vastness of the cultural divide between the young American and her subjects. Yet her youthful optimism that this gap could be bridged is one reason her island paintings are so powerful.

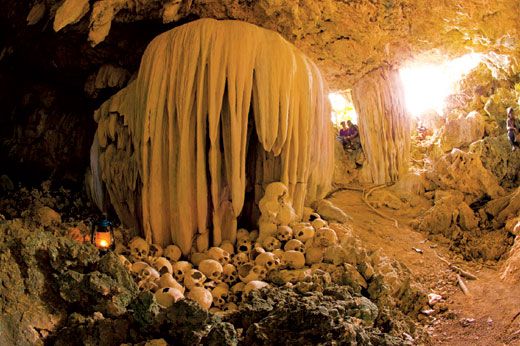

Another is Mytinger’s recognition that she was recording a world that was vanishing even as she painted it. Her last picture in the series, done in Australia, on the way to Java, depicted an aboriginal burial place, “a nice quiet grave with a solitary figure squatting beside the colorful graveposts,” she wrote. “It was symbolical....For this is the twilight hour for the earth’s exclusive tribes.”

In Mytinger's Footsteps

Photographer Michele Westmorland had traveled to Papua New Guinea many times when a friend of her mother’s pressed a copy of Caroline Mytinger’s book New Guinea Headhunt into her hands in 1994. “As soon as I read the book,” Westmorland says, “I knew that here was a story that needed to be told.”

Determined to retrace Mytinger’s travels, Westmorland began researching the reclusive artist’s life and spent years trying to locate the pictures Mytinger described in the two books she wrote about her South Seas travels. Finally, in 2002, Westmorland happened on a Web site listing the holdings in storage at the University of California’s Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology in Berkeley. The site, which had gone up just the day before, mentioned 23 paintings by Mytinger.

By then Westmorland had recruited another Seattle-based photographer, Karen Huntt, for the expedition. “When we went to the museum, we said we’d better prepare ourselves, in case the paintings were no good,” says Huntt. “When we saw the first one we had tears in our eyes. It was beautiful, and it was in perfect condition.”

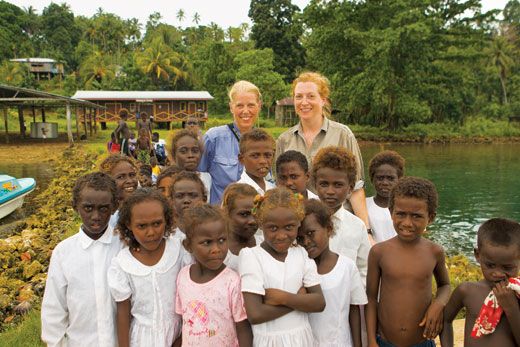

In the spring of 2005, the two women (above, in the village of Patutiva on the Solomon Island of Vangunu; Westmorland is at left) carried out their plan, leading a five-person team on a two-month journey to the Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. Along the way, they visited many of the same places that Mytinger and Margaret Warner had explored in the 1920s and documented how the lives and customs of the local people had changed.

In addition to cameras, computers and other equipment, Westmorland and Huntt brought with them large-format reproductions of Mytinger’s pictures. “The visual reference gave the native people an immediate understanding of why we had come and what we were trying to do,” Huntt reports. “This made them feel honored and proud, as they could see how respectfully Mytinger had portrayed their ancestors.” The pictures also helped the two photographers find the descendants of several of the people the artist had depicted, including the son of a man pictured in her Marovo Lagoon Family.

Now the two adventurers are raising an additional $300,000 for the next stage of the project—a documentary film they plan to produce from the more than 90 hours of footage they shot during their travels and a book and traveling exhibition of their photographs and Mytinger’s South Seas paintings. If they succeed, it will be the first major exhibition of Mytinger’s work in nearly 70 years.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.