The Smart and Swinging Bonobo

Civil war has threatened the existence of wild bonobos, while new research on the hypersexual primates challenges their peace-loving reputation

Led by five trackers from the Mongandu tribe, I tread through a remote rain forest in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, on the trail of the bonobo, one of the world's most astonishing creatures. Along with the chimpanzee, it's our closest relative, with whom we share almost 99 percent of our genes. The last of the great apes to be discovered, it could be the first to become extinct in the wild: in the past few decades, bonobo habitat has been overrun by soldiers, and the apes have been slaughtered for food. Most estimates put the number of bonobos left in the wild at less than 20,000.

As the narrow trail plunges into a gloomy, rain-soaked tunnel through tall trees, Leonard, the head tracker, picks up a fallen leaf and brings it to his nose. "Bonobo urine," he murmurs. High above I see a large, dark, hairy creature propped between the trunk and bough of a sturdy hardwood. "The alpha male," Leonard whispers. "He's sleeping. Keep quiet, because it means there are bonobos all around us."

We creep toward the tree and sit beneath it. I try to ignore the fiery bites of ants crawling over my arms and legs as we wait for the bonobos to awaken. They are known to be gregarious, exceptionally intelligent primates, and the only apes whose society is said to be matriarchal...and orgiastic: they have sexual interactions several times a day and with a variety of partners. While chimpanzees and gorillas often settle disputes by fierce, sometimes deadly fighting, bonobos commonly make peace by engaging in feverish orgies in which males have intercourse with females and other males, and females with other females. No other great apes—a group that includes eastern gorillas, western gorillas, Bornean orangutans, Sumatran orangutans, chimps and, according to modern taxonomists, human beings—indulge themselves with such abandon.

But when these bonobos awaken, their signature behavior is nowhere in evidence. Instead, dung splatters the forest floor, flung at us by the alpha male. "He's angry we're here," Leonard says softly. The male screams a warning to the other bonobos, and they respond with shrill cries. Through binoculars, I see many dark eyes peering down at me. A youngster shakes his fist at us. Moments later, the bonobos are gone, swinging and leaping from branch to branch, led across the rain forest canopy by the big male.

Because so much of what's known about these animals has been based on observing them in captivity or in other unnatural settings, even my first encounter with them in the wild was revelatory. The alpha male's bellicose display was just the first of several signs I would see over the next ten days that not all is peace and love in Bonoboland. Maybe it shouldn't be surprising, but this close relative of ours turns out to be far more complicated than people realized.

It was at Germany's Frankfurt Zoo some years ago that I first got hooked on bonobos. One of their nicknames is pygmy chimp, and I had expected to see a smaller version of the chimpanzee, with the same swagger and strut in the males and timorous fealty in the females. Bonobos are smaller than chimps, all right—a male weighs about 85 to 95 pounds and a female, 65 to 85 pounds; a male chimpanzee can weigh as much as 135 pounds. But the male bonobos I saw in the zoo, unlike the chimps, did not try to dominate the females. Both males and females strode about the enclosure picking up fruit and mingling with their friends. They looked strangely human with their upright, bipedal gait; long, slim arms and legs; slender neck; and a body whose proportions resemble ours more than they do a chimp's. More than anything, they reminded me of models I'd seen of Australopithecus afarensis, the "ape man" who walked the African savanna three million years ago.

In 1920, pioneer primatologist Robert Yerkes of Yale University named a bright young primate captured in the wild "Prince Chim." Comparing him with other chimpanzees he was studying, Yerkes said Prince Chim was an "intellectual genius." Only in 1929 did scientists realize that bonobos are a distinct species (Pan paniscus) and not just undersized chimps (Pan troglodytes), and we now know from photographs that Prince Chim was actually a bonobo.

The bonobo's life history is typical for a great ape. A bonobo weighs about three pounds at birth and is carried around by its mother for the first few years. She protects the youngster and shares her nest with it for the first five or six years. Females give birth for the first time at age 13 to 15; males and females reach full size at about age 16. They can live up to about 60 years.

Yerkes' observation of superior intelligence has held up over the years, at least in captive animals. Some primatologists are convinced that bonobos can learn to communicate with us on our own terms.

As I stood near the bonobo enclosure, an adolescent female named Ulindi reached through the bars and began to groom me, her long fingers tenderly searching through my hair for bugs. Satisfied I was clean, she offered her back for me to groom. After I did so (she, too, was bug-free), I left to pay my respects to the group's matriarch. Ulindi's eyes burned with indignation, but minutes later she drew me back with a sweet gaze. She looked at me with what seemed affection—and suddenly tossed into my face a pile of wood shavings she'd been hiding behind her back. She then flounced away.

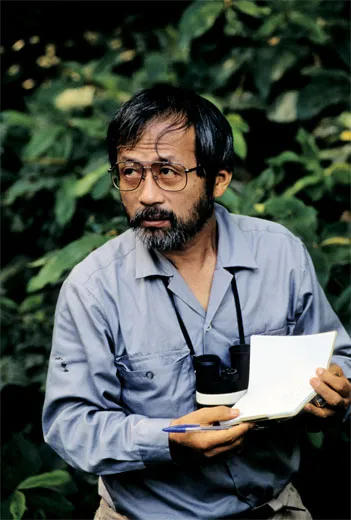

In 1973, a 35-year-old Japanese researcher named Takayoshi Kano, the first scientist to study bonobos extensively in the wild, spent months trudging through the dank forests of what was then Zaire (formerly the Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) before he finally encountered a foraging party of ten adults. To lure them out of the trees, Kano planted a field of sugar cane deep in their habitat. Months later, he spied a bonobo group, 40 strong, feasting on the cane. "Seeing them so close, they seemed more than animals, more a reflection of ourselves, as if they were fairies of the forest," Kano told me when I visited him in 1999 at Kyoto University's Primate Research Center.

Kano expected bonobo groups to be dominated by aggressive males. Instead, females sat in the middle of the sugar cane field. They groomed each other, snacked, chatted in squeaks and grunts, and invited favored males to sit with them. On the rare occasion that an angry male charged a group of females, Kano told me, they either ignored him or chased him into the jungle. Kano's observations shocked primatologists. "Among chimpanzees, every female of whatever rank is subordinate to every male of whatever rank," says Richard Wrangham, a Harvard University primatologist.

Over time, Kano came to recognize 150 different individuals, and he noticed a close attachment between certain females and males. Kano finally concluded he was watching mothers with their sons. "I saw mothers and sons stay together and realized that mothers were the core of bonobo society, holding the group together," he said.

One of the reasons to study primates is to better understand our own evolutionary history. Bonobos and chimps are our closest living links to the six million-year-old ancestor from which both they and we descended. As primatologist Frans de Waal points out, Kano's work "was a major revelation, because it proved the chimpanzee model was not the only one to point to our origins, that another primate akin to us had developed a social structure mirroring our own." When Kano's findings were publicized, in the 1970s, the animals' friendly family relations, peaceable males, powerful females, high I.Q.s and energetic sex lives made the idea of sharing an evolutionary lineage with bonobos appealing.

Wild bonobos live within several hundred thousand acres of dense swampy equatorial forest bounded by the Congo and Kasai rivers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Only 23 percent of their historic range remains undisturbed by logging, mining or war. From 1996 to 2003, the country suffered back-to-back civil wars, and foreign researchers and conservationists stayed out of bonobo territory, which saw some of the fiercest fighting. The New York-based International Rescue Committee estimates that the strife constituted the world's deadliest conflict since World War II, with five other African nations and numerous Congolese political factions fighting for territory and control of the DRC's immense natural resources—copper, uranium, petroleum, diamonds, gold and coltan, an ore used in electronics. Some four million people have been killed. The conflict officially ended in April 2003, with the ratification of a peace treaty between the DRC's young president, Joseph Kabila, who seized power after his father, Laurent, was assassinated in 2001, and several rebel groups. An uneasy truce has held since then, which has been tested during the run-up to a presidential election scheduled for October 29.

To observe bonobos in the wild, I fly to Mbandaka, capital of the DRC's Equateur Province, a destitute-looking city of more than 100,000 people by the Congo River. Civil war has left the city without water or electricity; mass graves of civilians executed by soldiers have been found on the city's outskirts. I embark with three foreign and seven Congolese conservation workers on a trip upriver by motorized pirogues, canoes hacked from tree trunks. We start on the Congo River, one of the world's longest at 2,900 miles from source to sea. Researchers say this geographic barrier, up to ten miles wide, has kept chimpanzees in jungles on the Congo River's north side and bonobos on the south, which allowed them to evolve into separate species.

As darkness drops a velvet curtain along the great waterway, we enter the Maringa tributary, which cuts deep into the heart of the Congo Basin. Twisting and turning like a giant snake, the Congo River is guarded on both banks by what Joseph Conrad, writing about it in Heart of Darkness, called a "great wall of vegetation, an exuberant and entangled mass of trunks, branches, leaves, boughs, festoons motionless in the moonlight." By day fish-eagles, herons, kingfishers and hornbills perch by the fast-flowing muddy water; local people pole canoes from their straw huts to market. At night the riverbanks echo with the urgent thump of unseen drums and raucous singing.

On our second morning, we pull in at Basankusu, a riverside town with a military base, where I show my permit to travel farther up the river. This area was a center of opposition to President Kabila, and government functionaries treat strangers with suspicion. Fierce battles between Kabila's forces and those of Jean-Pierre Bemba, who controlled the north, were waged here, and sunken barges still lie rusting in the shallows. According to the relief agency Doctors Without Borders, 10 percent of Basankusu's population perished over a 12-month period beginning in 2000. There is a brooding menace here, and I sense that a wrong word or movement could spark an explosion of violence. As our pirogue prepares to leave, a hundred soldiers led by shamans clad in leafy headdresses and skirts charge toward the river chanting war cries. "It's their morning exercise," a local man assures me.

All along the river I see grim evidence of the fighting. Much of the DRC's prewar export income came from rubber, timber and coffee plantations along the Maringa, but the riverside buildings are now deserted and crumbling, mangled by artillery fire and pockmarked by bullets. "The military looted everything along the river, even light sockets, and it'll take a long time to return to normal," says Michael Hurley, the leader of this expedition and executive director of Bonobo Conservation Initiative (BCI), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization.

By the fifth day, the river has narrowed to 20 yards, and the riverside villages have all but disappeared. Trees tower over us, and we slow to dog-paddle speed. At night a ghostly mist settles on the river. We tie the pirogues to reeds and camp on the boats, then leave at dawn just as the mist is rising.

On day six, 660 miles from Mbandaka, the riverbank throngs with villagers who have come to carry our supplies on a two-hour walk through the jungle to our destination, Kokolopori, a group of villages. Bofenge Bombanga, a powerful-looking shaman from the Mongandu tribe clad in a loincloth and headdress made from dried hornbill beaks, leads a welcoming dance. Afterward, in one of many tribal fables I will hear about the bonobos, he tells me that a village elder was once trapped high in a tree after his climbing vine came loose—and a passing bonobo helped him down. "Since then it has been taboo for villagers to kill a bonobo," he says through an interpreter.

But others say the taboo on bonobo meat is not observed in some areas. As a Congolese bonobo conservationist named Lingomo Bongoli told me, "Since the war, outsiders have come here, and they tell our young people that bonobo meat gives you strength. Too many believe them." In an informal survey of his village, more than one in four people admitted to having eaten bonobo meat. Soldiers—rebel and government—were the worst offenders.

In the village we are greeted by Albert Lokasola, once secretary general of the DRC's Red Cross and now head of Vie Sauvage, a Congolese conservation group. His group is working to establish a bonobo reserve on the 1,100 square miles of Kokolopori that are home to an estimated 1,500 bonobos. Vie Sauvage employs 36 trackers from local villages (at a wage of $20 per man per month) to follow five bonobo groups and protect them from poachers. It also funds cash crops such as cassava and rice and small businesses such as soap-making and tailoring to deter villagers from poaching. Funding for the project, about $250,000 per year, comes from BCI and other conservation groups.

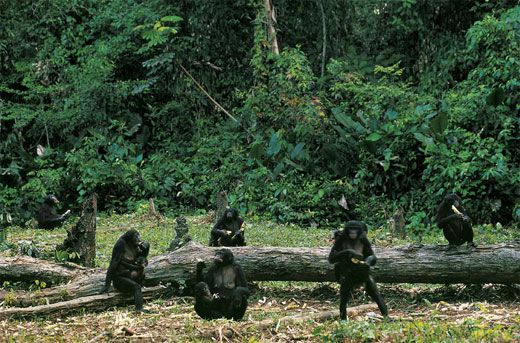

On day seven, after a tough trek scrambling over fallen trees and across slippery logs, we finally see what I have come all this way to see—bonobos, nine of them, part of the 40-member group known to local researchers as Hali-Hali. The first thing I notice is the animals' athletic build. At the Frankfurt Zoo, even males had the slim, elegant stature of ballet dancers, but jungle males are broad shouldered and well muscled, and the females too are bulky.

As he sits high on a limb munching fistfuls of leaves, the alpha male exudes dignity (even though he's the one who threw feces at me). Above us in the canopy, young and old bonobos are feasting. A male juvenile lies in the crook of a tree with one leg dangling down into space and the other resting at a right angle on the trunk, like a teenager on a sofa. Two females stop eating for a few moments to rub their swollen genitals together.

My heart stops as a youngster casually steps off a branch maybe 30 yards up and plunges toward the forest floor through branches and leaves. About ten yards before crashing into the ground, he grabs a branch and swings onto it. I'm told by the trackers that this death-defying game is a favorite among young bonobos, and invariably concludes with a wide grin on the acrobat's face.

Suddenly, the alpha male puckers his pink lips and lets loose a scream, a signal for the troop to move. He leads the way, hurtling from tree to tree just below the canopy. I stumble beneath them, trying to keep up, banging my head into low branches and tripping on vines spread like veins across the forest floor. After about 300 yards, the bonobos settle into another clump of trees and begin stripping branches and shoving leaves by the fistful into their mouths. About noon, they go to sleep.

When they wake after a couple of hours, the bonobos come down onto the ground, in search of plants and worms, moving so swiftly through the forest that we see them only as blurs of dark fur. I spy a female walking upright across a moss-covered log, her long arms held high in the air for balance like a tightrope walker.

As the setting sun paints the rain forest gold, the alpha male sits on a branch high above me and swings his human-like legs, for all the world appearing to be deep in thought as the sun slips below the canopy rim.

Later in the week, I follow the Hali-Hali group for 24 hours. I see that they spend much of the day feeding or dozing. At night, they settle in a clump of trees high in the canopy and build their springy nests, yanking leafy branches and weaving them into resting places. Chimps build night nests too, but theirs are not as elaborate as bonobo cradles, which resemble giant bird nests. Their chatter drifts away, and by 6 p.m., as the light leaches from the sky, each bonobo has settled out of sight in a leafy bed.

The trackers and I retreat for half an hour through the jungle. I crawl into a one-man tent, while the trackers sleep in the open around a fire they keep going all night to ward off leopards. At 5 a.m., I crouch with the trackers beneath the trees as the bonobos wake, stretch and eat leaves and fruits growing next to their nests—breakfast in bed, bonobo-style. A female swings to the next tree and rubs genitals with another female for about a minute, squeaking, while a male and a female, balanced on a bough, mate face to face, her legs wrapped around his waist. An hour later the troop swings off into the jungle. No one knows exactly why bonobos have sex so often. One leading explanation is that it maintains bonds within the community; another is that it prevents males from knowing which infants they sired and thus encourages them to protect all of the young in a group. Bonobo males are affectionate and attentive to infants; chimpanzee males, in contrast, are known to kill the offspring of rival males.

Back at camp, I meet with two Congolese researchers from the Ministry of Scientific Research and Technology. They had ridden bikes 35 miles along a jungle path from the village of Wamba. One of them, Mola Ihomi, spends the year at Wamba collecting bonobo data to share with researchers from Kyoto University, the same institution at which Kano worked years ago. The bonobo groups studied so far usually range in size from 25 to 75 members. The animals have what primatologists call a fission-fusion social structure, in which the group gathers together at night to sleep but splits into smaller parties during the day to forage. The groups include males and females, adults and young.

Bonobo researchers no longer lure their subjects with sugar cane. In fact, Ihomi says, some scientists point out that Kano observed bonobos in an unnatural situation. Normally, bonobos eat leaves and fruit, and there's plenty to go around. But enticed into the sugar cane field, the animals were out of their treetop habitat and competing for a concentrated resource. By watching bonobos in more natural settings, Ihomi and others have discovered that females are not necessarily as dominant as they appeared in the sugar cane field. "The alpha male is usually in charge," Ihomi says. The alpha male determines where the troop eats and sleeps and when it moves, and he is the first to defend the troop from leopards and pythons. But bonobo society is still much less authoritarian than that of other great apes. "If the alpha female doesn't want to follow him, she sits there and then the rest of the troop follows her lead and don't move," Ihomi says. "She always has the last say. It's like the alpha male is the general and the alpha female is the queen."

Researchers also now believe that the bonobo creed of making love, not war, is not as absolute as earlier studies suggested. Near Wamba, Ihomi says, he and his colleagues tracked three bonobo groups, two of which engaged in rambunctious sex when they ran into each other. But when the groups ran into the third group, "which isn't often," he says, "they display fiercely to defend their territory, males and females screaming, throwing dung and sticks at each other. They even fight, sometimes inflicting serious bite wounds."

Primatologists still regard bonobos as peaceful, at least compared with chimpanzees and other great apes, which are known to fight to the death over females or territory. Ihomi says, "I have never seen a bonobo kill another bonobo."

The effort to save wild bonobos is hampered by a lack of basic information. One urgent chore is to determine how many of the animals are left in the wild. By all estimates, their numbers are well down since the 1970s. "Political instability, the threat of renewed civil war, a surging human population, the thriving bush-meat trade and the destruction of bonobo habitat in the DRC is hurrying them toward extinction in the wild," says Daniel Malonza, a spokesman for The Great Apes Survival Project, a United Nations body set up five years ago to arrest the dramatic decline of the great apes.

In Mbandaka, Jean Marie Benishay, BCI's national director, showed me a photograph of bonobo skulls and bones that had been on sale at a village market for use in rituals. The seller told him the six bonobos had come from an area near Salonga National Park, southwest of Kokolopori, where they were once common but are rarely sighted these days. Gruesome as the photograph was, Benishay looks encouraged. "They come from a place where we thought bonobos had disappeared," he said with a grim smile. "This proves bonobos are still out there."

In the past two years, Paul Raffaele has reported for the magazine from Uganda, the Central African Republic, Zimbabwe, Cameroon, Niger, Australia, Vanuatu and New Guinea.