100 Days That Shook the World

The all-but-forgotten story of the unlikely hero who ensured victory in the American Revolution

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/hundred-main_388.jpg)

Winter clouds scudded over New Windsor, New York, some 50 miles up the Hudson River from Manhattan, where Gen. George Washington was headquartered. With trees barren and snow on the ground that January 1781, it was a "dreary station," as Washington put it. The commander in chief's mood was as bleak as the landscape. Six long years into the War of Independence, his army, he admitted to Lt. Col. John Laurens, a former aide, was "now nearly exhausted." The men had not been paid in months. They were short of clothing and blankets; the need for provisions was so pressing that Washington had dispatched patrols to seize flour throughout New York state "at the point of the Bayonet."

At the same time, many Americans felt that the Revolution was doomed. Waning morale caused Samuel Adams, a Massachusetts delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, to fear that those who had opposed independence in 1776 would gain control of Congress and sue for peace with Britain. During the past two years, three American armies—nearly 8,000 men—had been lost fighting in the South; Georgia and South Carolina appeared to have been reconquered by Great Britain; mutinies had erupted in the Continental Army and the nation's economy was in shambles. Washington was aware, he wrote to Laurens, that the "people are discontented." Convinced that the army was in danger of collapse, Washington predicted darkly that 1781 would prove America's last chance to win the war. Nothing less than the "great revolution" hung in the balance. It had been "brought...to a crisis."

Yet within a matter of months, a decisive October victory at Yorktown in Virginia would transform America's fortunes and save the American Revolution. The victory climaxed a brilliant—now largely forgotten—campaign waged over 100 fateful days by a former foundry manager totally lacking in military experience at the outset of the war. Yet it would be 38-year-old general Nathanael Greene who snatched "a great part of this union from the grasp of Tyranny and oppression," as Virginia founding father Richard Henry Lee would later tell Greene, when the two met in 1783.

In the early days of the war, Britain had focused on conquering New England. By 1778, however, it was clear that this would not be achieved. England's crushing defeat at Saratoga, New York, in October 1777—British general John Burgoyne's attempt to invade from Canada resulted in the loss of 7,600 men—had driven London to a new strategy. The South, as Britain now perceived it, was tied by its cash crops, tobacco and rice, to markets in England. The region, moreover, abounded with Loyalists; that is, Americans who continued to side with the British. Under the so-called Southern Strategy as it emerged in 1778, Britain would seek to reclaim its four former Southern colonies—Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia—by expelling rebel forces there; regiments of Loyalists, also called Tories, would then occupy and pacify the conquered areas. If the plan succeeded, England would gain provinces from the Chesapeake Bay to Florida. Its American empire would remain vast and lucrative, surrounding a much-reduced and fragile United States.

At first, the new strategy met with dramatic success. In December 1778, the British took Savannah, stripping the "first...stripe and star from the rebel flag of Congress," as Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell, the British commander who conquered the city, boasted. Charleston fell 17 months later. In August 1780, the redcoats crushed an army led by Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates at Camden, South Carolina. For the Americans, the desperate situation called for extreme measures. Congress removed Gates and asked Washington to name a successor to command the Continental Army in the South; he chose Greene.

Nathanael Greene's meteoric rise could hardly have been predicted. A Quaker whose only formal schooling had been a brief stint with an itinerant tutor, Nathanael was set to work in his teens in the family-owned sawmill and iron forge. In 1770, he took over management of the foundry. In 1774, the last year of peace, Greene, then 32, married Catherine Littlefield, a 19-year-old local beauty, and won a second term to the Rhode Island assembly.

Later that year, Greene enlisted as a private in a Rhode Island militia company. When hostilities between Britain and the Colonies broke out at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, on April 19, 1775, Greene was suddenly elevated from the rank of private to brigadier general—doubtless a result of his political connections—and named commander of Rhode Island's force. Although he had begun as what his fellow officer Henry Knox called, in a letter to a friend, "the rawest, the most untutored" of the Continental Army generals, he rapidly gained the respect of Washington, who considered Greene's men to be, he wrote, "under much better government than any around Boston." During the first year of the war, Washington came to regard Greene as his most dependable adviser and trusted officer, possessed not only with a superb grasp of military science but also an uncanny facility for assessing rapidly changing situations. By the fall of 1776, rumor had it that should anything happen to Washington, Congress would name Greene as his successor.

It was Washington's confidence in Greene (who, since 1776, had fought in campaigns in New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island, and had served two years as the Continental Army's quartermaster general) that caused the commander in chief to turn to him as the war crisis deepened in the autumn of 1780. Greene was commander of the Continental installation at West Point when he learned of his appointment on October 15. He hastened to Preakness, New Jersey, where the Continental Army's main force was camped, to confer with Washington. Soon after Greene's departure from New Jersey, he received a letter in which Washington soberly advised: "I can give you no particular instructions but must leave you to govern yourself intirely [sic], according to your own prudence and judgment and the circumstances in which you find yourself." On December 2, Greene took command of what was left of Gates' army, in Charlotte, North Carolina—some 1,000 thin and hungry Continentals and 1,200 militiamen, all of them, Greene said, "destitute of every thing necessary either for the Comfort or Convenience of Soldiers." He told the governor of North Carolina, Abner Nash, that he had inherited "the Shadow of an Army,...a small force...very incompetent to give Protection" to the Carolinas. Greene, writing to Washington, assessed his prospects for success as "dismal, and truly distressing." But he knew that should he fail, the entire South, as his cavalry commander, Henry Lee, put it, "would be ground to dust" and face "reannexation to the mother country."

Greene was also fully aware that he faced a formidable British opponent. After the fall of Charleston in May 1780, Charles, Earl Cornwallis—usually referred to as Lord Cornwallis—had been ordered to pacify the remainder of South Carolina. The 42-year-old Cornwallis had fought against France in the Seven Years' War (1756-63) and had seen considerable action against the American rebels since 1776. Unassuming and fearless, the British general treated his men with compassion, but expected—and got—much from them in return. By early summer 1780, six months before Greene would arrive in Charlotte, Cornwallis' men had occupied a wide arc of territory, stretching from the Atlantic Coast to the western edge of South Carolina, prompting British headquarters in Charleston to announce that resistance in Georgia and South Carolina had been broken, save for "a few scattering militia." But the mission had not quite been accomplished.

Later that summer, backcountry patriots across South Carolina took up arms. Some of the insurgents were Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who simply longed to be free of British control. Others had been radicalized by an incident that had occurred in late May in the Waxhaws (a region below Charlotte, once home to the Waxhaw Indians). Cornwallis had detached a cavalry force under Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton, by reputation hard and unsparing, to mop up the last remaining Continentals in that area, some 350 Virginians under Col. Abraham Buford. Tarleton's 270-man force had caught up with Buford's retreating soldiers on May 29 and quickly overwhelmed them. But when the Continentals called for quarter—a plea for mercy by men who had laid down their arms—Tarleton's troops hacked and bayoneted three-quarters of them to death. "The virtue of humanity was totally forgotten," a Loyalist witness, Charles Stedman, would recall in his 1794 account of the incident. From then on, the words "Bloody Tarleton" and "Tarleton's quarter" became a rallying cry among Southern rebels.

Following Buford's Massacre, as it soon came to be called, guerrilla bands formed under commanders including Thomas Sumter, Francis Marion and Andrew Pickens. Each had fought in South Carolina's brutal Cherokee War 20 years earlier, a campaign that had provided an education in irregular warfare. Soon, these bands were emerging from swamps and forests to harass redcoat supply trains, ambush forage parties and plunder Loyalists. Cornwallis issued orders that the insurgents would be "punished with the greatest vigour."

Two months of hard campaigning, however, failed to quash the insurgency. In late summer, Cornwallis, writing to Sir Henry Clinton, commander, in New York, of the British Army in North America, admitted that the backcountry was now "in an absolute state of rebellion." After acknowledging the risk entailed by expanding the war before the rebellion had been crushed, Cornwallis was nevertheless convinced, he informed Clinton, that he must invade North Carolina, which was "making great exertions to raise troops."

In September 1780, Cornwallis marched 2,200 men north to Charlotte. Meanwhile, he dispatched 350 Loyalist militiamen under Maj. Patrick Ferguson, a 36-year-old Scotsman, to raise a force of Loyalists in western North Carolina. Ferguson was flooded with enlistments; his force tripled within two weeks. But backcountry rebels, also, were pouring in from the Carolinas, Georgia, Virginia and what is now eastern Tennessee. More than 1,000 rendezvoused at Sycamore Shoals in North Carolina, then set off after the Tories. They caught up with Ferguson in early October on King's Mountain, near the border between the Carolinas.

There Col. William Campbell, leader of the Virginians, a red-haired, 6-foot-6 giant married to the sister of firebrand patriot Patrick Henry, exhorted his men to "Shout like hell and fight like devils." Indeed, as the rebels hurtled up the steep hillside, they shrieked a hair-raising battle cry learned from Indian warriors. At the summit, they overwhelmed their foe, shouting "Buford! Buford! Tarleton's quarter!" The victors killed Ferguson and desecrated his body. Loyalists were slain after they surrendered. Altogether, more than 1,000 of them were killed or captured.

Upon hearing the news, Cornwallis, still in Charlotte, immediately retreated 60 miles south to Winnsboro, South Carolina. He remained there into December, when he learned that Greene had taken command of the tiny Continental Army and redeployed it to Hillsborough, North Carolina, roughly 165 miles northeast. Cornwallis knew that Greene possessed barely one-quarter the strength of the British force. Spies also informed him that Greene had made a potentially fatal blunder: he had divided his army in the face of a numerically superior foe.

In that audacious move, made, Greene said, "partly from choice and partly from necessity," he had given 600 men to Gen. Daniel Morgan, a tough former wagon master who had joined the army in 1775. After sending Morgan west of Charlotte, Greene marched the remainder of the force, 800 or so troops, toward the Pee Dee River, 120 miles to the east. His strategy was simple: if Cornwallis pursued Greene, Morgan could liberate British-held posts in western South Carolina; if the British went after Morgan, Greene wrote in a letter, there would be "nothing to obstruct" Greene's forces from attacking British posts in the backcountry outside Charleston. Other factors also figured into his unconventional plan. As his army, Greene wrote, was "naked & destitute of everything" and the countryside was in an "impoverished condition," he believed that "provisions could be had" more readily if one division operated in the east, the other in the west. Furthermore, the smaller armies could "move with great celerity," forcing the redcoats to give chase to one of them, and, Greene hoped, exhaust themselves.

But Cornwallis also divided his force. He dispatched Tarleton with 1,200 men to destroy Morgan, while he set off after Greene with 3,200 troops. Within a week, Tarleton caught up with Morgan, who had fallen back, buying time for the arrival of reinforcements and scouting for the best place to fight. He chose Cowpens, a meadow 25 miles west of King's Mountain. By the time Morgan positioned his army there, his force had swelled to 1,000.

Near 6:00 a.m. on January 17, Tarleton's men splashed across Macedonia Creek, pushing to the edge of the meadow, moving, an American soldier later recalled, "as if certain of victory." Tarleton's force advanced the length of two football fields in three minutes, huzzahing as they came, drums beating, fifes sounding, sunlight gleaming off bayonets, "running at us as if they Intended to eat us up," Morgan would write a few days later. He ordered his forward line to open fire only when the British had closed to within 35 yards; at that instant, as one American soldier wrote in a letter home, a "sheet of flame from right to left" flashed toward the enemy.

After three such volleys, the Americans retreated. Believing the militiamen to be fleeing, Tarleton's men surged after them, only to run into a fourth deadly volley, laid down by Continentals posted in a second line behind the militiamen. Morgan then unleashed his cavalry, which materialized from behind a ridge; the horsemen, slashing with their sabers, bellowed "Tarleton's quarter." The "shock was so sudden and violent," one rebel would recall, that the British quickly retreated. Many threw down their weapons and ran, said another, "as hard...as a drove of wild Choctaw steers." About 250 of the British, including Tarleton, escaped. Many of those who could not flee fell to their knees, pleading for their lives: "Dear, good Americans, have mercy on us! It has not been our fault, that we have SKIVERED so many." The cavalrymen showed little mercy, an American, James Collins, reported later in his memoirs, attacking both armed and unarmed men, sweeping the battlefield like a "whirlwind."

While 73 of Morgan's rebels were killed, Tarleton had lost nearly everything. More than 100 British corpses littered the battlefield. Another 800 soldiers, a quarter of them wounded, had been captured, along with artillery, ammunition and baggage wagons. Morgan was euphoric. He swept up his 9-year-old drummer, kissed him on both cheeks, then cantered across the battlefield shouting: "Old Morgan never was beaten." Tarleton, he crowed, had been dealt "a devil of a whipping."

When Cornwallis learned of the rout at Cowpens the following day, January 18, he took the news badly. One witness, an anonymous American prisoner of war, reported that the general leaned "forward on his sword....Furious at what he heard, Cornwallis pressed so hard that the sword snapped in two, and he swore loudly." Now Cornwallis decided to go after Morgan, then hunt down Greene. After a five-day march, Cornwallis and nearly 3,000 men reached Ramsour's Mill in North Carolina. There he learned that Morgan was a mere 20 miles ahead of him. Cornwallis stripped his army of anything that might slow it down, burning nearly his entire baggage train—tents, wagons, luxury goods—in a giant bonfire.

Morgan's scouts reported this development. "I know thay [sic] intend to bring me to an action, which I carefully [plan] to avoid," Morgan wrote to Greene, informing him also that Cornwallis enjoyed a two-to-one numerical superiority. Though Morgan had gotten a considerable head start, he now paused to await orders from Greene after crossing the Catawba River on January 23. He was still there five days later when he learned that the enemy had closed to within ten miles. "I am a little apprehensive," Morgan confessed in a dispatch to Greene, as "my numbers...are too weak to fight them....It would be advisable to join our forces." Cornwallis' army reached the opposite shore of the Catawba later that day. But the gods of war were with Morgan. It began to rain. Hour after hour it poured, transforming the river into a raging, impassable barrier. Cornwallis was stopped in his tracks for nearly 60 hours.

Greene had not learned of Cowpens until January 24, and while the news set off a great celebration at his headquarters, two more days passed before he discovered that Morgan had lingered at the Catawba awaiting orders. Greene sent most of his men toward the relative safety of Salisbury, 30 miles east of the Catawba, then, accompanied only by a handful of guards and his small staff, set off to join Morgan, riding 80 mud-splattered miles through Tory-infested territory. As he rode, Greene considered his options: make a stand against Cornwallis at the Catawba or order Morgan's men to retreat east and link up with their comrades near Salisbury. His decision, Greene concluded, would depend on whether sufficient reinforcements from local militias had marched to Morgan's aid.

But when he reached Morgan on January 30, Greene learned that a mere 200 militiamen had turned up. Incensed, he immediately wrote Congress that despite his appeal for reinforcements, "little or nothing is done....Nothing can save this country but a well appointed army." Greene ordered a retreat to the village of Guilford Courthouse, North Carolina, 75 miles east. He also requisitioned "vessels and watermen" to transport his army across the rivers that lay ahead and appealed to civil authorities for reinforcements. "Great god what is the reason we cant Have more men," he wrote in frustration to Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia.

If enough soldiers arrived by the time his combined armies reached Guilford Courthouse, Greene could engage Cornwallis. If not, he would continue north toward the Dan River, cross into Virginia and await additional troops there. Greene preferred to fight, but he saw too that his retreat was drawing Cornwallis ever deeper into the interior, farther and farther from reinforcements, compelling the British to forage for every scrap of food. And, since the bonfire at Ramsour's Mill, the redcoats had been without tents and sufficient winter clothing. Greene hoped that the cold weather and arduous marches over roads that rain had turned into quagmires would further weaken them.

Greene set out on January 31, but without Morgan. Since the previous fall the subordinate had suffered back problems; now, Morgan said, "a ciatick pain in my hip...renders me entirely [in]capable of active services." Greene sent him ahead, to join the contingent of British prisoners from Cowpens being marched to Winchester, Virginia. Greene took command of Morgan's men, pointed that force toward the Yadkin River, seven miles beyond Salisbury, and hoped that transport vessels awaited them.

Only 12 hours after Greene had crossed the Catawba, Cornwallis, too, began to move his army across it. Lacking boats and facing a raging current, the British had to wade across the numbingly cold, four-foot-deep river, while Greene's rear guard—North Carolina militiamen—poured a steady fire into their ranks. Cornwallis himself had his horse shot from under him. "I saw 'em a snortin, a hollerin and a drownin," wrote a Tory. By the time the last of Cornwallis' men made it across the 500-yard-wide river, Greene had increased his lead to 30 miles.

Cornwallis pressed on, hoping the rain—his enemy at the Catawba—would prove his ally at the Yadkin; if it persisted, the rebels might be trapped. Having kept the hundreds of horses he had used to pull supply wagons, he ordered two redcoats astride each mount; the entire force pressed forward through the mud, closing in on their quarry. Greene reached the Yadkin first, where he indeed found boats awaiting him. But just as Cornwallis had hoped, Greene faced a river roiling with floodwaters. To attempt a crossing would be hazardous; yet to stand and fight, backed against the river, would be madness. Greene ordered his army into the vessels. It was a harrowing crossing; the boats nearly capsized and Greene himself barely made it across. His rear guard exchanged shots with Cornwallis' vanguard. But for the British, crossing without vessels was unthinkable. For the second time in a week, Cornwallis had been stopped by a rampaging river.

Marching under threatening skies, the Americans now hurried to Guilford Courthouse. There, at last, the two divisions of Greene's army, separated since before Christmas, were reunited. Greene convened a council of war to decide whether to fight or retreat into Virginia. His officers, knowing their force to be outnumbered by at least 1,000, voted unanimously "to avoid a general Action at all Events" and to fall back.

Cornwallis, meanwhile, cooled his heels waiting—for five long days—to cross the Yadkin. His men were bone-tired, but the general was a man possessed. If he could destroy Greene, not a single Continental soldier would remain south of Virginia. Cornwallis envisioned then taking his army into Virginia, where he would cut supply lines to guerrillas in the Carolinas and Georgia. He was convinced that once partisans there were denied the stores that were their lifeblood, they could not hold out. The consummation of Britain's Southern Strategy, Cornwallis believed, lay within his grasp. Once again, he pressed on. But Greene was no less determined. He told North Carolina's governor that although "evils are now fast approaching," he was "not without hopes of ruining Lord Cornwallis."

The final leg of the chase began on February 10, as the redcoats, chilled to the bone, doggedly moved out. The next day, Greene, who was 25 miles ahead at Guilford Courthouse, set out for Boyd's Ferry, on the Dan River. Greene knew he must stay ahead. "Our force is so unequal to the enemy, as well in numbers as condition," he wrote, that fighting Cornwallis would mean "inevitable ruin to the Army."

Again, Greene divided his army. He replaced the incapacitated Morgan with Col. Otho Williams, a 32-year-old former civil servant from Frederick, Maryland, who had fought in Canada and New York. Williams was to take 700 men and head northwest, as if he planned to cross the Dan at its upper fords. Greene, commanding a larger division of some 1,300 men, would stay to the east, marching directly for a downstream crossing. Williams made every minute count. He woke his men each morning at 3:00, marching them four hours before pausing for a hurried breakfast. He did not give them another break until after nightfall, when they were allotted six hours for supper and sleep.

But if the rebels moved quickly, Cornwallis moved even faster. By February 13, he had cut the gap with Williams to a mere four miles. Though Cornwallis knew he could not catch Greene's forces before they reached the Dan, he believed he could pinion Williams at the river and deliver a fatal blow. Spies had reported that Williams had no boats.

But Cornwallis had been hoodwinked. With the redcoats running hard on his heels, Williams suddenly veered, as planned, toward Greene and Boyd's Ferry. Greene, who had ordered vessels readied at that site, reached the river the next day, February 14, and crossed. He immediately wrote Williams: "All our troops are over....I am ready to receive you and give you a hearty welcome." Williams reached the Dan just after nightfall the next day. Ten hours later, in the tilting red light of sunrise on February 16, Cornwallis arrived just in time to witness the last rebel soldier step ashore on the far side of the Dan.

The chase had ended. Greene's men had marched 200 miles and crossed four rivers in less than 30 days, waging a campaign that even Tarleton later praised as "judiciously designed and vigorously executed." Cornwallis had lost one-tenth of his men; the remainder had been exhausted by their punishing, and fruitless, exertions. Ordering an end to the pursuit, he issued a proclamation claiming victory, on the grounds that he had driven Greene's army from North Carolina. Cornwallis then retreated to Hillsborough, 65 miles south.

But Greene had not given up the fight. Only eight days after crossing the Dan and longing to achieve a resounding victory, he returned to North Carolina with 1,600 men. As Greene headed toward Hillsborough, members of his cavalry, commanded by Col. Henry Lee, surprised an inexperienced band of Tory militiamen under Col. John Pyle, a Loyalist physician. In an action disturbingly similar to Tarleton's Waxhaws massacre, Lee's men slaughtered many of the Loyalists who had laid down their arms. American dragoons killed 90 and wounded most of the remaining Tories. Lee lost not a single man. When he heard the news, Greene, grown hardened by the war, was unrepentant. The victory, he said, "has knocked up Toryism altogether in this part" of North Carolina.

Cornwallis was now more eager than ever to engage Greene, who had halted to wait for reinforcements. Initially, Cornwallis had held a numerical advantage, but he could not replace his losses; after Pyles' Massacre, the recruitment of Loyalists virtually ceased. The rebel force, meanwhile, grew steadily as militia and Virginia Continentals arrived. By the second week in March, Greene possessed nearly 5,000 men, approximately twice Cornwallis' force.

Greene chose to meet Cornwallis near Guilford Courthouse, at a site he described as "a Wilderness" interspersed with "a few cleared fields." The thickly forested terrain, he thought, would make it difficult for the British to maintain formation and mount bayonet charges. He positioned his men much as Morgan had done at Cowpens: North Carolina militiamen were posted in the front line and ordered to fire three rounds before they fell back; a second line, of Virginia militiamen, would do the same, to be followed by a third line of Continentals. Around noon on March 15, a mild spring day, the rebels glimpsed the first column of red-clad soldiers emerging through a stand of leafless trees.

The battle was bloody and chaotic, with fierce encounters among small units waged in wooded areas. Ninety minutes into it, the British right wing was continuing to advance, but its left was fraying. An American counterattack might have turned the battle into a rout. But Greene had no cavalry in reserve, nor could he be sure that his militiamen had any fight left in them. He halted what he would later call the "long, bloody, and severe" Battle of Guilford Courthouse, convinced that his troops had inflicted sufficient losses. Cornwallis had held the field, but he had lost nearly 550 men, almost twice the American casualties. The "Enemy got the ground," Greene would write to Gen. Frederick Steuben, "but we the victory."

A decisive triumph had eluded Greene, but the heavy attrition suffered by the British—some 2,000 men lost between January and March—led Cornwallis to a fateful decision. Convinced it would be futile to stay in the Carolinas, where he would have to either remain on the defensive or resume an offense that promised only further "desultory expeditions" in "quest of adventures," Cornwallis decided to march his army into Virginia. His best hope of turning the tide, he concluded, was to win a "war of conquest" there. Greene allowed him to depart unimpeded, leading his own forces south to liberate South Carolina and Georgia.

Although Greene reentered South Carolina with only 1,300 men (most of his militia had returned home) to oppose nearly 8,000 redcoats there and in Georgia, the British were scattered across the region, many in backcountry forts of between 125 and 900 men. Greene took them on systematically. By the end of the summer, the backcountry had been cleared of redcoats; Greene announced that no "further ravages upon the Country" were expected. What was left of the British Army was holed up in Savannah and Charleston.

Just nine months earlier, it had appeared that the Carolinas and Georgia were lost, leaving the fledgling nation—if it even survived—as a fragile union of no more than ten states. Greene's campaign had saved at least three Southern states. Now Cornwallis' presence in Virginia gave General Washington and America's ally, France, the possibility of a decisive victory.

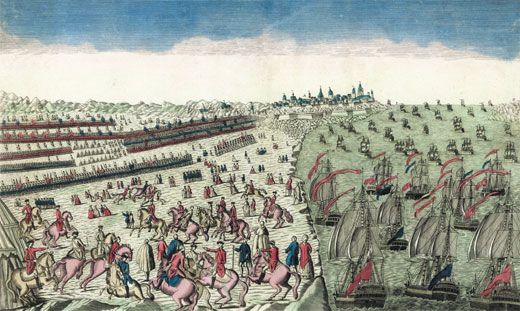

In August, Washington and his French counterpart, Comte de Rochambeau, learned that a French fleet under Comte de Grasse had sailed from the Caribbean for the Chesapeake with 29 heavy warships and 3,200 troops. Both men knew that Cornwallis' army had camped at Yorktown, on the peninsula below Richmond, near de Grasse's destination. While Franco-American forces headed south from New York, Washington asked the Marquis de Lafayette and his Continental forces to confine Cornwallis to the peninsula. When the combined allied armies arrived outside Yorktown in late September, they found that Lafayette had hemmed in Cornwallis and that de Grasse's fleet had prevented the Royal Navy from entering the Chesapeake and rescuing the beleaguered redcoats.

Cornwallis was trapped. His 9,000 men faced an enemy of 7,800 French soldiers, 8,000 Continentals and 3,100 American militiamen. One American soldier noted that the allies had "holed [Cornwallis] and nothing remained but to dig him out." The allies mounted a siege. Cornwallis held out for three grim weeks, but by mid-October, with disease breaking out in the ranks and his men on half-rations, he opened surrender negotiations. Two days later, on October 19, under a clear autumn sky, Cornwallis' soldiers emerged from the village of Yorktown, marching between a long line of French on their left and Americans on their right, to lay down their arms. It was the decisive outcome Washington had long sought, setting in motion the negotiations that eventually resulted in Britain's recognition of American independence.

In the wake of Cornwallis' surrender, General Washington congratulated the army for "the glorious event" that would bring "general Joy" to "every Breast" in the United States. To General Clinton in New York, Cornwallis wrote: "I have the mortification to inform Your Excellency that I have been forced to...surrender the troops under my command." Pleading illness, he did not attend the surrender ceremony.

Washington understood that Greene's campaign had saved the American Revolution. In December, he told Greene that there "is no man...that does not allow that you have done great things with little means." To "save and serve the Country" was the most noble of attainments, Thomas Paine informed Greene. General Knox declared that Greene, without "an army, without Means, without anything has performed Wonders." No tribute was more important to Greene than the award of a Congressional Medal, bearing his likeness on one side, under the epigraph "The Distinguished Leader"; the reverse was inscribed with a Latin phrase that translated: "The Safety of the Southern Department. The Foe conquered...."

Greene said little of his own achievements, preferring instead to express his gratitude to his men. When he at last left the army in July 1783, Green praised his "illustrious" soldiers: "No Army," he proclaimed, "ever displayed so much obedient fortitude because No army ever suffered such variety of distresses."

At first, when Greene retired from military service, he divided his time between Newport, Rhode Island, and Charleston, South Carolina. The state of Georgia, as a token of gratitude for his role in liberating the South, had given Greene a rice plantation, Mulberry Grove, outside Savannah. In the autumn of 1785, he and Catherine moved to the estate. However, they lived there for only eight months before Greene died, either of an infection or sunstroke, on June 19, 1786. He was 43 years old.

Historian John Ferling is the author of Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence, published this month by Oxford University Press.