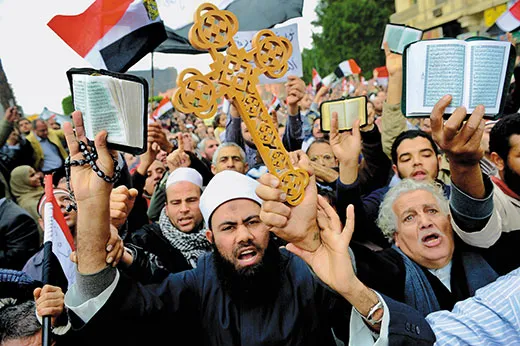

A New Crisis for Egypt’s Copts

The toppling of Egypt’s government has led to a renewal of violence against the nation’s Christian minority

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Copts-Christians-and-Muslims-Cairo-631.jpg)

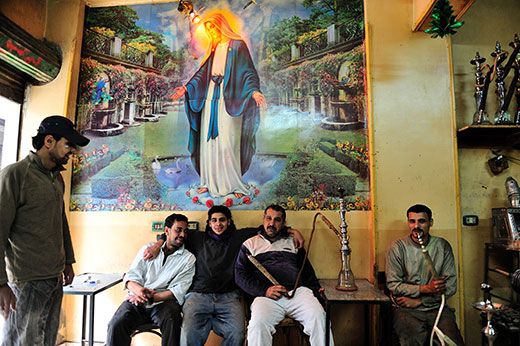

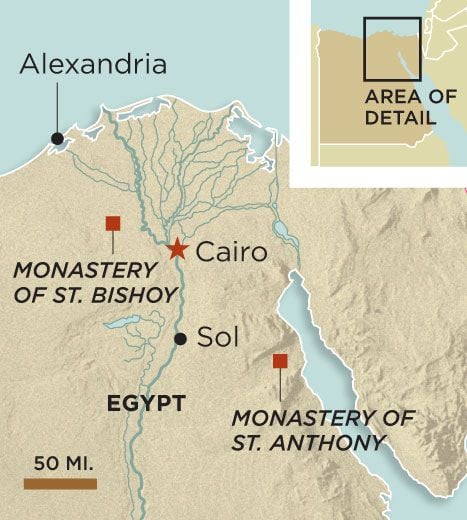

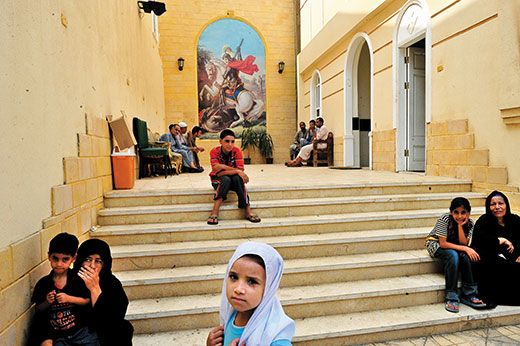

Fakhri Saad Eskander leads me through the marble-tiled courtyard of the Church of St. Mina and St. George in Sol, Egypt. We pass a mural depicting St. George and the Dragon, climb a freshly painted staircase to the roof and gaze across a sea of mud-brick houses and date palm trees. Above us rises a white concrete dome topped by a gold cross, symbols of Coptic Christianity. The church—rebuilt after its destruction by an Islamic mob four months earlier—has a gleaming exterior that contrasts with the dun-brown townscape here, two hours south of Cairo. “We are grateful to the army for rebuilding our church for us,” says Eskander, a lean, bearded man of 25 who wears a gray abaya, a traditional Egyptian robe. “During the time of Mubarak, this would never have been possible.”

Eskander, the church custodian, was on the roof the night of March 4 when some 2,000 Muslims chanting “Death to Christians” arrived at the compound in fevered pursuit of a Coptic man believed to have taken refuge inside. The man had been involved with a Muslim woman—taboo throughout Egypt—setting off a dispute that ended only when the woman’s father and cousin had shot each other dead. The pair had been buried that afternoon, and when a rumor spread that another Christian was using the church to perform black magic against Muslims, “the whole town went crazy,” Eskander says.

He leads me downstairs into the chapel. As the sun filters through stained-glass windows, he and a Muslim acquaintance, Essam Abdul Hakim, describe how the mob knocked down the gates, then set the church on fire. On his cellphone, Hakim shows me a grainy video of the attack, which shows a dozen young men smashing a ten-foot log against the door. The mob then looted and torched the homes of a dozen Christian families across the street. “Before the January 25 revolution there had always been security,” Eskander tells me. “But during the revolution, the police disappeared.”

One hopeful thing did come from the attack. During the 30-year era of Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, who this past August was hauled to court in his sickbed to face murder and corruption charges, outbreaks of sectarian violence were typically swept under the rug. This time, YouTube videos spread on the Internet, and journalists and human rights workers flocked to Sol. In addition, Muslim leaders in Cairo, as well as Coptic figures, traveled to the town for reconciliation meetings. And the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the 20-member panel of generals that took power after Mubarak stepped down this past February, dispatched a 100-man team of army engineers to reconstruct the church. With a budget of two million Egyptian pounds (about $350,000), they finished the job in 28 days. When I got to town in July, a small contingent of troops was laying the foundation of an adjoining religious conference center that had also been destroyed.

Repairing the psychic damage will take longer. “At the beginning I was filled with hate,” Eskander tells me. Today, though he still regards his Muslim neighbors with distrust, he says his anger has abated. “I realized that not all Muslims are the same,” he says. “I have started to calm down.”

The Coptic branch of Christianity dates to the first century A.D. when, scholars say, St. Mark the Evangelist converted some Jews in Alexandria, the great Greco-Roman city on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. (The name Copt derives from the Arabic word Qubt, meaning Egyptian.) Copts now make up between 7 percent and 10 percent of the country’s population, or 7 million to 11 million people, and are an integral part of Egypt’s business, cultural and intellectual life. Yet they have long suffered from discrimination by the Muslim majority. Violent incidents have increased alarmingly during the wave of Islamic fanaticism that has swept the Middle East.

On New Year’s Day 2011, a bomb exploded in the birthplace of the Coptic faith, Alexandria, in front of al-Qiddissin church, the largest of the city’s 60 Coptic churches, as worshipers were leaving midnight Mass. Twenty-one died. “We all rushed into the street and saw the carnage,” said Father Makkar Fawzi, the church’s priest for 24 years. “Those who had gone downstairs ahead of the rest were killed.” Alexandria “has become a focal point of the [Islamic fundamentalists], a breeding ground of violence,” says Youssef Sidhom, the editor of Watani (Homeland), a Coptic newspaper in Cairo.

Since the New Year’s Day bombing, sectarian attacks against Egypt’s Copts have escalated. Forty Egyptians died in 22 incidents in the first half of this year; 15 died in all of 2010. Human rights groups say the breakdown of law and order in the first months after Mubarak’s ouster is partly to blame. Another factor has been the emergence of the ultraconservative Salafist Muslim sect, which had been suppressed during the Mubarak dictatorship. Salafists have called for jihad against the West and the creation of a pure Islamic state in Egypt. “They announced that their role is to defend ‘real Islam,’” says Watani’s Sidhom, “and that the tool they would use is the early Islamic penal code.”

In one incident this past March, Salafists attacked a 45-year-old Copt in the Upper Egyptian town of Qena, slicing off his ear. The Muslims claimed the man had had an affair with a Muslim woman. “We have applied the law of Allah, now come and apply your law,” the assailants told police, according to the victim’s account. Salafists were also blamed for the violence that erupted in Cairo on May 8, after a rumor spread that a female Christian convert to Islam had been kidnapped and was being held captive in a Cairo church. Led by Salafists, armed crowds converged on two churches. Christians fought back, and when the melee ended, at least 15 people lay dead, some 200 were injured and two churches had been burned to the ground.

In half a dozen other Arab countries, the rise of Islamic militancy (and, in some cases, the toppling of dictatorships) has spread fear among Christians and scattered their once-vibrant communities. One example is Bethlehem, the West Bank birthplace of Jesus, which has lost perhaps half its Christians during the past decade. Many fled in the wake of the al-Aqsa intifada of 2000-2004, when the Palestinian territories’ economy collapsed and Muslim gangs threatened and intimidated Christians because of their alleged sympathies with Israel. In Iraq, about half of the Christian population—once numbering between 800,000 and 1.4 million—is thought to have fled the country since the U.S. invasion toppled Saddam Hussein in 2003, according to church leaders. Offshoots of Al Qaeda have carried out attacks on churches across the country, including a suicide bombing at Our Lady of Salvation Church in Baghdad in October 2010 that killed 58 people.

Ishak Ibrahim, a researcher for the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, a watchdog group based in Cairo, worries that social unity is coming undone. “The Egyptian people gathered in Tahrir Square to achieve the same end,” he says. “Then everyone went back home, retreated to his beliefs, and the fighting began again.” Backed by elements of the Egyptian armed forces, the Muslim Brotherhood—the multinational social, religious and political organization known for the slogan “Islam is the solution”—has gained support across the country in advance of parliamentary elections to begin on November 28. Some predict the brotherhood could pick up as many as half the seats in the assembly. If that should happen, some Christian leaders fear that many of Egypt’s Copts would flee the country.

One Friday morning I took a taxi through quiet Cairo streets to the city’s ancient Coptic quarter. It was just after the Friday liturgy, and well-dressed Coptic families strolled hand in hand down a wide road that led past a fifth-century church and the Coptic Museum, an Ottoman-era villa containing ancient mosaics, sculptures, illuminated manuscripts and other treasures culled from Egypt’s desert monasteries. I wandered past security police down an alley that dated to Roman times and entered the Church of St. Sergius and Bacchus, a fourth-century basilica named for two Syrian converts to Christianity martyred by Roman authorities. Originally a Roman palace, the basilica is built over a crypt where, according to legend, Joseph, Mary and Jesus stayed during their exile in Egypt. According to the Book of Matthew, Joseph had been warned in a dream to “take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt, and stay there until I tell you, for Herod is about to search for the child, to destroy him.” Legend also holds that the family remained in Egypt for three years, until the angel returned and announced Herod’s death.

It was around A.D. 43, according to religious scholars, that a Coptic community began to take root in the Jewish districts of Alexandria. Seventy years later, the Roman emperor Trajan crushed the last revolt of Alexandria’s Jews, nearly annihilating the community. A Christian faith—embraced by Greeks, the city’s remaining Jews and some native Egyptians—began to spread, even in the face of brutal persecution. Holy men such as the abbot Antonius (later St. Anthony) retreated into the desert, where living as hermits in grottoes, they established Christianity’s first monasteries. From a.d. 380, when the emergent faith became the official religion of the Roman Empire, until the Arab conquest of the empire’s Byzantine successors in the seventh century a.d., Coptic Christianity enjoyed a golden age, and the monasteries became centers of scholarship and artistic ferment. Some, such as St. Anthony’s by the Red Sea, still stand. “There are thousands and thousands of cells carved into the rocks in the most inaccessible places,” wrote the French diplomat Benoît de Maillet of the region in Description of Egypt in 1735. “The anchorite saints could reach these caves only by way of very narrow paths, often blocked by precipices, which they crossed on small wooden bridges that could be removed on the other side, making their retreats inaccessible.”

Around a.d. 639, a few thousand horsemen led by the Arab general Amr ibn al-As swept into Egypt, encountering little resistance. Arabic replaced Coptic as the national language, and the Copts, though permitted to practice their faith, steadily lost ground to a tide of Islam. (The Copts split from the Roman and Orthodox churches in a.d. 451 in a dispute over Christ’s human and divine natures, though they continued to follow the Orthodox religious calendar and share many rituals.) By the year 1200, according to some scholars, Copts made up less than half of the Egyptian population. Over the next millennium, the fortunes of the Copts rose and fell depending on the whims of a series of conquerors. The volatile Caliph al-Hakim of the Fatimid dynasty confiscated Christian goods, excluded Christians from public life and destroyed monasteries; the Kurdish warlord Saladin defeated the European Crusaders in the Holy Land, then allowed Copts to return to positions in the government. Under the policies of the Ottomans, who ruled from the 16th century until the end of World War I, the Copts resumed their long downward spiral.

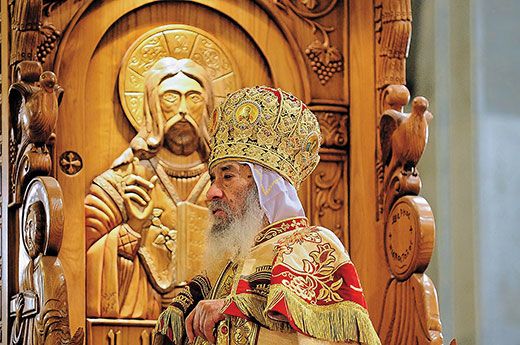

For the past few decades, the Copts have maintained an uneasy relationship with Egypt’s military rulers. During the 1970s, Copts suffered a wave of attacks by Muslim extremists, and when President Anwar Sadat failed to respond to their demands for protection in 1981, Pope Shenouda III, the patriarch of Alexandria and head of the Coptic church, canceled Easter celebrations in protest. Sadat deposed Shenouda in September 1981 and exiled him to the Monastery of St. Bishoy in the Nitrian Desert. The pope was replaced by a committee of five bishops, whose authority was rejected by the Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church.

Sadat was murdered by members of the radical Egyptian Islamic jihad in October 1981; his successor, Mubarak, reinstated Shenouda four years later. Shenouda supported Mubarak’s repressive policies as a bulwark against Islamic extremism. Yet Christians continued to suffer from laws that made building a church nearly impossible (most are constructed illicitly). Despite the rise to powerful government positions of a few Copts, such as former secretary general of the United Nations Boutros Boutros-Ghali, who had served as foreign minister under Sadat and Mubarak, Coptic participation in public life has remained minimal. In the first days of the 2011 revolution, Shenouda continued his support for Mubarak, urging Copts not to join the protesters in Tahrir Square. After that, Sidhom told me, many Copts “rejected the leadership of Shenouda in the political arena.”

After my visit to Coptic Cairo, I drove 70 miles northwest to Wadi Natrun, the center of monastic life in Egypt and the desert valley in which the exiled Holy Family supposedly took refuge, drawn here by a spring. In the middle of the fourth century, anchorite holy men established three monasteries here, linked by a path known as the Road of Angels. But after most of the monks abandoned them, the monasteries fell into disrepair, only to flourish again in the past two decades as part of an anchorite revival.

I drove past scraggly acacia trees and date plantations through a sandy wasteland until I arrived at the mud-walled Monastery of St. Bishoy, founded in a.d. 340, and the place where Shenouda spent his years in exile. A sanctuary of baked-mud-brick monastic quarters and churches, linked by narrow passageways and topped by earthen domes, the compound has changed little over the past 1,500 years. Boys were sweeping the grounds and trimming hedges of oleander and bougainvillea in the monastery’s garden. (The youngsters are laborers’ sons, who receive a free education as recompense for their work.) As I turned a corner, I walked into a monk wearing Ray-Ban sunglasses. He introduced himself as Father Bishoy St. Anthony and offered to serve as my guide.

He escorted me into the original, fourth-century church, and showed me the bier containing the remains of St. Bishoy, who died in Upper Egypt at age 97 in a.d. 417. We crossed a wooden drawbridge to a sixth-century fortress of thick stone walls and vaulted corridors, built for protection from periodic attacks from Berbers. From the rooftop, we could see a huge new cathedral, guesthouse and cafeteria complex built on the orders of Pope Shenouda after his release. “At the time [of Shenouda’s exile], the economy of the monastery was very bad, most of the monks had left,” Father Bishoy said. Today St. Bishoy comprises a community of 175 monks from as far away as Australia, Canada, Germany and Eritrea. All commit themselves to remain here for life.

Like many monks, Bishoy St. Anthony, 51, turned to the spiritual life after a secular upbringing in Egypt. Born in Alexandria, he moved to New York City in his 20s to study veterinary medicine but found himself yearning for something deeper. “I had this thought in America day and night,” he said. “For three years, I stayed in a church in Brooklyn, to serve without money, and the thought stayed with me.” After taking his vows, he was assigned to small St. Anthony Coptic Monastery outside Barstow, California—from which he took his name—then was dispatched to a church in Tasmania, off Australia’s southern coast. He spent two years there, serving a mix of Eritreans, Egyptians and Sudanese, then lived in Sydney for four years. In 1994, he returned to Egypt.

Now Bishoy St. Anthony follows a daily routine nearly as ascetic and unvaried as that of his fourth-century predecessors: The monks wake before dawn; recite the Psalms, sing hymns and celebrate the liturgy until 10; take a short nap; then eat a simple meal at 1. After the meal, they cultivate beans, corn and other crops on the monastery’s farms and perform other tasks until 5, when they pray before taking a meditative walk alone in the desert at sunset. In the evening, they return to their cells for a second meal of yogurt, jam and crackers, read the Bible and wash their clothes. (During the fasting periods that precede both Christmas and Easter, the monks eat one meal a day; meat and fish are stricken from their diet.) “There is no time for anything here, only church,” he said.

Yet Bishoy St. Anthony acknowledged that not all of the monks here dwell in complete isolation. Because of his language skills, he has been entrusted with the role of liaison with foreign tourists, and like the monks who purchase fertilizer and pesticides for the monastery’s agricultural operations, he carries a cellphone, which brings him news from the outside world. I asked how the monks had reacted to Mubarak’s downfall. “Of course, we have an opinion,” he said, but declined to say more.

Back in Cairo, one stifling hot afternoon I snaked past a dust-shrouded landscape of tenements and minarets to a district called Nasr (Victory) City. The quarter was partly designed by Gamal Abdel Nasser, who, with other junior military officers, overthrew King Farouk in 1952 and ushered in 60 years of autocratic rule. The trial of 24 men involved in the mayhem in Cairo this past May was about to start in Cairo’s Emergency Court, a holdover of the Mubarak years. The men, mostly Salafists, were being tried under emergency laws enacted after the Sadat assassination that have yet to be repealed.

Christians had welcomed the swift justice following the May attacks; the Salafists were outraged. Several hundred ultraconservative Islamists gathered in the asphalt plaza in front of the courthouse to protest the trial. Police barricades lined the street, and hundreds of black-uniformed security police—Darth Vader look-alikes wearing visors and carrying shields and batons, deployed during the Mubarak years to put down pro-democracy protests—stood by in tight formation. Protesters brandished posters of the most prominent defendant, Mohammed Fadel Hamed, a Salafist leader in Cairo who “gets involved in conversion issues,” as one protester put it to me. Hamed had allegedly incited his Salafist brethren by spreading a rumor that the would-be Islamic convert, Abeer Fakhri, was being held against her will inside Cairo’s Church of St. Mina.

Members of the crowd shook their fists and chanted anti-government and anti-Christian slogans:

“This is not a sectarian problem, it is a humanitarian case.”

“A Coptic nation will never come.”

“State security is sleeping about what is going on in the churches.”

An Egyptian journalist, who spoke on condition of anonymity, watched the scene with some surprise. “Now Salafists have the freedom to gather, while before state security would have squashed them,” she told me.

Three days later, at a packed political conference at Al- Azhar University in Cairo, I met Abdel Moneim Al-Shahat, the burly, bearded head of the Salafist movement in Alexandria. The sect had started a political party, Al Nour, and was calling for an Islamic state. Yet Al-Shahat insisted that Salafists believe in a pluralistic society. “Salafists protected churches in Alexandria and elsewhere during the revolution,” he said, insisting that the May church burnings were instigated by “Christians who felt that they were losing power [under the new regime].” He did not elaborate.

Christian leaders are understandably divided over Egypt’s incipient democratic process. Some fear it will open the way for further discrimination against Copts; others say that it will encourage Islamists to moderate their views. There is similar disagreement about the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces. Christians cheered the rapid reconstruction of the three burned churches in Cairo and Sol. “They really fulfilled this commitment graciously,” Youssef Sidhom told me. And the military government has advocated a Unified Law for Places of Worship, which would remove strictures that make building a church in Egypt nearly impossible. But Sidhom says that some members of the council have cozied up to Islamic fundamentalists and the justice system has fallen short. The Copt whose ear was severed was persuaded by local government officials to drop the case. And none of those who destroyed the church in Sol have been arrested.

Sheik Mahmoud Yusuf Beheiri, 60, a Muslim community leader who lives a few blocks from the Church of St. Mina and St. George in Sol, defended the decision not to pursue the culprits, saying that doing so “would create even more hatred between people. Also, the number was so big that this would not be practical. Also, they were just crazy youth.” Beheiri told me he had sheltered some two dozen Christians whose homes were being looted, adding that he hoped he had set an example in the town. “Religious figures have a big role now,” he said. “Sheiks have to educate their youth, priests have to educate their youth, on how relationships between Muslims and Christians should be. This is the best way to prevent this from happening again.”

Down the street, in his airless office at the church, Father Basili Saad Basilios, 44, who is St. Mina and St. George’s priest, sounded less optimistic. The church burning, he said, wasn’t the first act of violence against Christians in the town. In 2000, the Copt who founded the church was shot by Muslim attackers; his murder was never solved. “If it were an isolated case, I wouldn’t have had Pampers full of excrement thrown at me on the street,” he told me. Still, he said he would “turn the other cheek” and carry on. Basilios’s predecessor as head priest couldn’t muster the same resolve. The day after the church was burned, Basilios said, he fled to Cairo, vowing never to return.

Joshua Hammer is based in Berlin. Photographer Alfred Yaghobzadeh is working on a project documenting the Copts.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Screen_Shot_2021-09-15_at_12.44.05_PM.png)