A Short Walk in the Afghan Countryside

On their way to a park built in the shadow of Bamiyan’s Buddhas, two Americans encounter remnants of war and signs of promise

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/Bamiyan-mud-brick-homes-631.jpg)

After a week in Kabul, I traveled by van to the Bamiyan Valley, most famous, in recent history, for being the place where the Taliban blew up two giant stone Buddhas in 2001. I planned to visit and maybe offer a little help to the Bamyan Family Park, an enormous enclosed garden with flowers and caged parakeets and swing sets and fountains, where Afghan families—especially women—can stroll and play. My friend Marnie Gustavson oversees the park, but she was stuck in Kabul running the venerable PARSA, a nonprofit that’s helped widows, orphans, the wounded and other Afghans since 1996, and she couldn’t come along.

“Be sure you get out and walk around,” she said before I left the PARSA compound.

“In the park?”

“No, everywhere! Bamyan is one of the safest, most peaceful places in Afghanistan.”

Kabul felt anything but safe and peaceful on this trip, my fourth since 2005. It took a while to break free of the city’s orbit, even though we left at 4 a.m. I had assumed Kabul was dustiest during the day, with all those cars grinding the dirt streets to dust and spinning it into the air. But it was even worse at night, when truck convoys rumble through the city and create a choking haze of diesel and dust. We passed through several checkpoints on our way out, the officials at each demanding to know what we were transporting in the back of the van. Flowers, we said. They opened the back of the van, stared at the pots of petunias and bougainvillea intended for the park, then waved us on. Soon we escaped the traffic and the helicopters and the fancy new villas wearing multiple verandas like so many garish ruffles and reached the countryside, where the traditional Afghan architecture—mud-brick buildings surrounded by mud compound walls—took over.

The road to the Hazarajat—the land of the Hazara people, an ethnic group especially ill-treated by the Taliban--is a long one. Until recently, the road was so terribly rutted and narrow that the trip took eleven hours. Road crews have been working steadily with bulldozers, shovels, and bare hands, and it now takes nine hours. By next year, some say it will be down to four, making it a plausible destination for the tourists so desired by Habiba Sarabi, Bamiyan’s governor and the single female governor in all of Afghanistan. But even at nine hours, it was a mostly riveting ascent through the mountains to the Shibar Pass and then a blissful descent into the Bamiyan Valley’s brilliant green farmlands. Beyond the fields, Bamiyan is surrounded by jagged red cliffs crowned with ruins and smoother brown inclines with mineral stains of black, yellow and green, and, beyond these, the gleaming white teeth of the Koh-e-Baba Mountains.

A male friend and I decided to walk from Bamiyan City out to the Bamiyan Family Park, as it was such a delicious novelty to actually walk anywhere in Afghanistan. In Kabul, I had been piloted from one place to another by a driver. Whenever I reached my destination, I called whomever I was meeting and a security guard rushed out to escort me inside. It was maddening to shoot past the city streets pulsing with life and color and be told by everyone that it wasn’t safe to spend more than a moment on them.

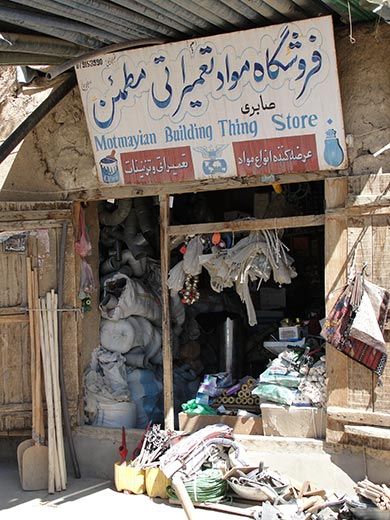

Bamiyan City is like a tiny slice of the Kabul I glimpsed from those speeding cars. There are row after row of tiny shops built into mud buildings or old shipping containers, many with brilliantly colored signs indicating the shop’s retail purpose in Dari, English and, often, pictures. My friend and I strolled the main drag, beginning with the spice shops, then the fruit and vegetable stalls, then the dry-goods stores and bookshops, then the antiquities and handicrafts stores. The lights in the stores flared as we entered and dimmed as we exited; finally, I noticed that a boy followed us with a small gas generator, bringing power to each store we entered. We chatted along the way with townspeople, who seemed pleased to have korregi (foreigners) in their midst. Of course, we were friendlier than usual—I don’t normally speak to everyone I see—but here I said “Salaam” (although on a few idiotic occasions, “Shalom”) and pressed my hand to my heart. They did the same.

When we reached the end of town and headed out into the countryside, people really began to take notice. At the checkpoint near the city’s periphery, the shocked guards perused my passport, then helped me climb on the rusting Russian tank still parked on the side of the road. “Don’t go farther!” they joked. “Taliban out there!”

They couldn’t figure out why two korregi were out walking, and neither could any of the other Afghans we encountered as we tromped into the countryside. They weren’t walking. They were driving cars or trucks, or riding bicycles or motorcycles, or piloting their oxen through fields or planting potatoes. They waved at us and many stopped what they were doing. “Come to my house for tea,” a half dozen said, in combinations of English, Dari and gesture. Others pointed at my camera and posed with their hoes or their donkeys. We walked and we walked, past shattered mud-brick dwellings that could have been 300 years old or 30. We passed homes built into old caves on the cliffs. We accumulated a gaggle of schoolboys who juggled and stood on their bicycles to show off and chatted for several miles until they reached the roads to their villages. When we passed trucks parked for lunch in the shade of a poplar forest, one of the truckers—with a large black beard and an impossibly white prayer cap--stared at us intently. I started to wonder if the guards by the tank might not have been joking; I felt that if anyone was Taliban, it was this ferociously bearded man. Then he reached into the cab of his truck and handed us bottles of water and yellow apples.

As it turned out, I had grossly miscalculated the distance to the Bamiyan Family Park. Later, we figured out that we had only walked about eight miles, but it felt like 50 with the sun beating down and radiating off those rocky cliffs. We rested in whatever shade we could find and hoped to find the stone walls of the park around every curve. Finally, we passed yet another field where a family was planting potatoes. The matriarch strode over with a big smile and shook our hands and asked us to tea. She was so extraordinarily friendly that I wondered if she was remembering the distant 1960s, when hippies camped along the river in the Bamiyan Valley and the sight of ambling, unarmed korregi was a pretty decent indicator of stability. I saw the gleam of her kettle against the fence and was about to follow her back through the furrows. Why continue to decline this most Afghan of gifts, hospitality and generosity even when she and her family had so little to give?

But just then, our friends drove up and carried us back to the park. We had our tea and some lunch on the terrace above the playground. Boisterous men in their 20s had taken over the swings and the slides and the jiggly wooden bridge between two elevated platforms, and they were vying to see who could make the other lose his balance. Soon, a musician began singing Hazara ballads near the park’s main fountain and the men left. From nowhere, it seemed, women in jewel-colored scarves and their children arrived to claim the playground.

Kristin Ohlson is the co-author of The Kabul Beauty School: An American Woman Goes Behind the Veil. Her trip to Afghanistan is funded by a Creative Workforce Fellowship from the Community Partnership for Arts and Culture.

Planning Your Next Trip?

Explore great travel deals

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.